The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

CSS at-rules are very practical in terms of telling CSS how to behave. There are several of these rules like @media, @import, @font-face, and more. The unique identifier is the @ mark that comes before these rules.

To make things simpler, these rules can be divided into two groups, general rules and nesting rules. In this post, we’ll cover the most practical and useful rules in each group with code examples.

First, we will cover general CSS at-rules. These rules need to be placed on top of the stylesheet, before all the other CSS attributes and properties because they are defining the general settings of the CSS rules and will not be overwritten by other rules.

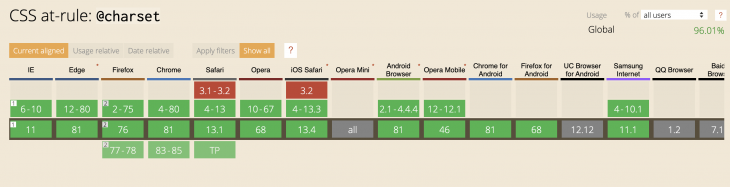

This is the first CSS at-rule that needs to be declared in the stylesheet for defining character encoding and no other rules should precede it. There are other ways of handling charset, like placing it on the HTTP header, but there are certain use cases for declaring it in CSS. For example, when we are using non-ASCII characters for the content property, the browser has different ways of figuring out the character encoding.

Setting it in the calling HTML file:

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

The server might set content type with a certain character encoding, in the response header:

Content-Type: text/css; charset=utf-8

So in most cases, this is managed, but in case the encoding of the calling or returned HTML is different from a certain stylesheet, then @charset needs to be declared in the CSS file.

Here is an example of @charset usage:

@charset supports a good range of browsers, except early versions of Safari.

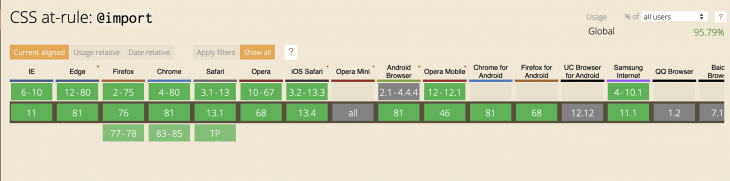

We use this rule to include CSS from another source in a current CSS file. So when parsing the CSS file and encountering a @import rule, the browser makes an HTTP request to fetch the external stylesheet and include its CSS properties right where the @import rule is declared. With this, it is important to note that this rule must be declared before all other rules except @charset. Let’s explore a few more facts about this CSS rule.

Since this rule was built to help developers include stylesheets from other sources, it is not possible to include it within any of the conditional group at-rules like @media, @page, and @document:

// THIS IS WRONG /* iPhone in Portrait and Landscape */ @media only screen @import 'custom.css'; }

However, we can specify media-dependent @import rules, to avoid fetching resources for unsupported media types. Here is an example:

@import 'custom.css' screen and (orientation:landscape);

This rule has very good browser support and almost all of the legacy browsers support it.

Due to the popularity of CSS preprocessors like SASS, it might be inevitable to mistake the @import property used in SASS with the native CSS one. Although they are very similar, they have their differences.

The SASS @import is an extension to the native CSS one which allows importing both .scss and .css files. In the case of importing .scss files, all of the mixins, variables, and functions used in the stylesheet will become available at the line of @import definition. However, the biggest difference between the two is that declaring @import in CSS makes multiple HTTP requests to fetch the stylesheet and render the page, while SASS imports are completely handled at compilation time which is more performant.

Here’s an example of @import:

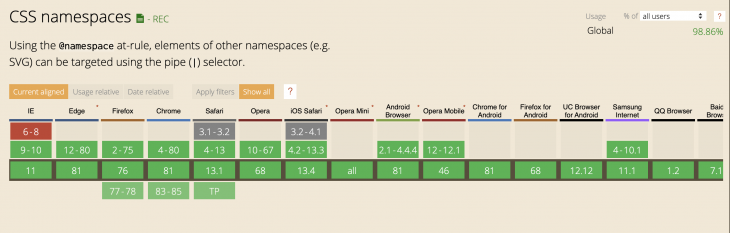

This rule was designed to help XML based namespaces that would prevent duplicate styles from interfering with each other. Even though there are more sophisticated concepts like SMACSS, there could be potential use cases for this rule in our CSS.

In a nutshell, the @namespace rule helps apply scoping for CSS that mix styles from different XML namespaces. Examples of XML namespaces are HTML, SVG, MathML, XLink, etc. This way, there will be no styling collisions between elements from different namespaces:

In terms of browser support, @namespace covers a good range of most browsers, except IE 6-8.

There is a subset of CSS at-rules that store a subset of statements within them. They usually follow up after the general rules we discussed above.

This is a unique rule that allows you to specify styles for a certain page, without affecting the styles of other pages. This page-based style customization comes in different forms:

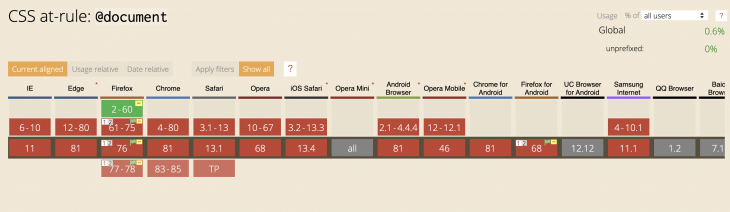

@document url(https://example.com/),

@document url-prefix(https://example.com/index),

@document domain(example.com),

@document regexp("https:.*"),

Remember that @document rule has limited browser support at this time.

There was a time when developers and designers were limited to the number of fonts that they can use to style web pages. As a matter of fact, you can see the list of most common and famous websafe CSS fonts, which a lot of people relied on for styling their pages because thy came pre-installed on users’ systems.

Then @font-face CSS rule was introduced as one of the pathways toward using custom fonts on the web, bringing more stylish typographies to web pages. Additionally, with the progress toward modernizing web fonts and usage of web open font format (WOFF/WOFF2), the future of web typography looks very exciting.

@font-face is a nested rule, and with it, you get different properties for defining the font, but two of the primary ones are src and font-family.

With font-family, you get access to an identifier name for your custom font when and if it is downloaded and available to be used. For example:

@font-face {

font-family: "CustomFont";

}

// Possible usage

p {

font-family: 'CustomFont';

}

With src, you define the source of the font data. The font data can come from an external source using url() or local one using local(). This way, if the font is not available locally in the site directory or user system, it will be downloaded from the external source.

Additionally, you can pass a format parameter, to hint toward the format of the defined font:

@font-face {

font-family: 'Helvetica';

src: url('Helvetica') format('woff'),

local('Helvetica.woff') format('woff');

}

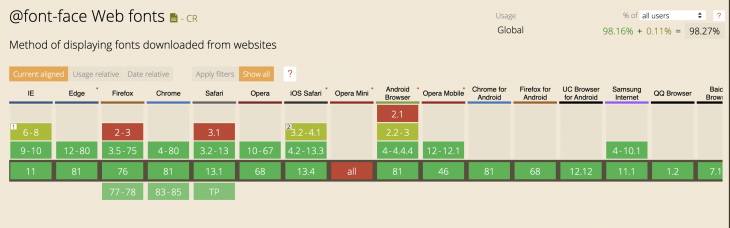

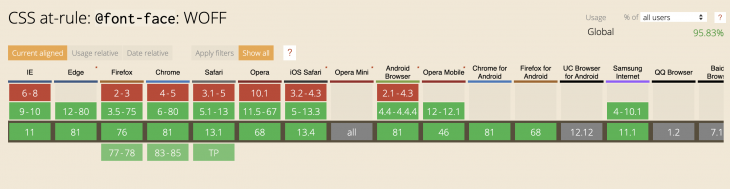

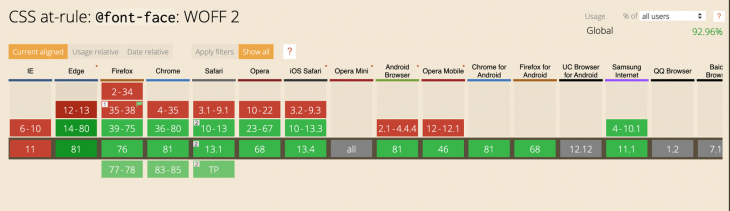

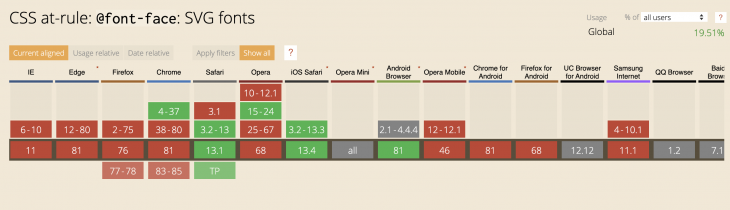

Now, when it comes to browser support for @font-face, most browsers do support the functionality of defining custom fonts in your CSS, but differ in the type of font that can be used in them.

As we know, WOFF2 is the next generation of web fonts that has better compression and will be the standard in the future, but until then we need to support older browsers as well.

For supporting older IE browsers (6-9), you can use the below method. .eot is the web font developed by Microsoft and is only available through IE browsers:

@font-face {

font-family: 'CustomFont';

src: url('customfont.eot'), /* IE9 */

url('customfont.eot?#iefix') format('embedded-opentype'); /* IE6-IE8 */

}

For modern browsers that do support .woff, you can use the below method:

@font-face {

font-family: 'CustomFont';

url('webfont.woff') format('woff');

}

For even more modern browsers that support woff2, you can use the following rule:

@font-face {

font-family: 'CustomFont';

url('webfont.woff2') format('woff2');

}

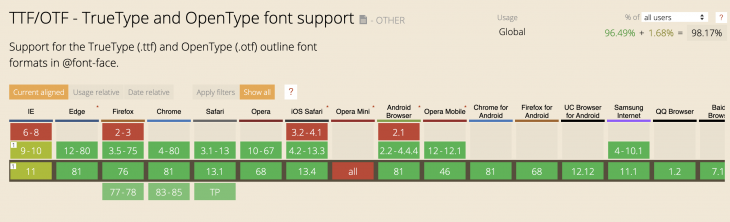

Some Android or iOS devices are reliant on .ttf, which is called TrueType Font. This is the font that .woff and .woff2 were originated from. The issue with this font was the fact that it could be copied easily without the consent of the font creator. You can use this font as a legacy support for some of the mentioned devices:

@font-face {

font-family: 'CustomFont';

url('customfont.ttf') format('truetype');

}

And finally, some legacy iOS browsers support .svg fonts. Because of the lighter size of SVG, it was an ideal use case for older browsers, especially for iOS. But none of the newer versions support this type. So in case you need to support older iOS Safari browsers, make sure to add this as a fallback in your @font-face rule:

@font-face {

font-family: 'CustomFont';

url('customfont.svg#svgFontName') format('svg');

}

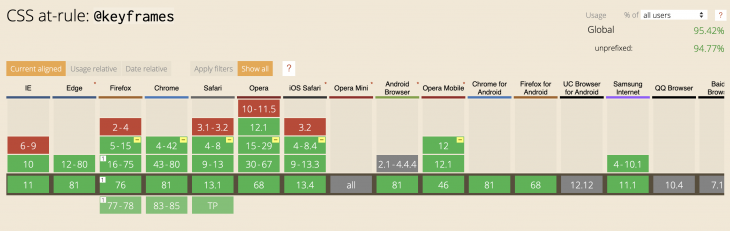

This is a very handy rule for defining CSS animation rules. So with the CSS rules applied within @keyframes rule, we define CSS rules that need to be applied when the CSS animation name attached to the @keyframe rule is applied to an element. Let’s see how this is done in action:

// CSS

@keyframes ANIMATION-NAME {

0% { opacity: 0; }

100% { opacity: 1; }

}

// OR

@keyframes ANIMATION-NAME {

from { opacity: 0; }

to { opacity: 1; }

}

With this approach, we are defining the lifecycle of the animation and CSS rules that needs to be applied for different parts of this lifecycle. This is a simple example that sets the animation with just two steps (0% and 100%):

We can get much more creative when it comes to defining CSS animations with @keyframe. For example, here we are defining a bouncing animation that is applied to the circle:

The browser support for this rule is very good among modern browsers. However, older versions of IE (6-9), Firefox (below v4), and Opera (below 12) are not supported.

This is one of the most common CSS at-rules, used for setting CSS styles that will be applied to elements at different screens and window sizes. This is mainly used for responsive design, so developers can style elements at different window sizes that tend to resemble common mobile, tablet, and desktop devices. Let’s see an example in action:

#box {

background-color: green;

}

@media only screen and (max-width: 600px) {

#box {

background-color: yellow;

}

}

With the above CSS rule, we are saying that we want to change the color of the box element to yellow when the browser window size is 600px or less. Otherwise, we set the box color to green on window sizes above 600px:

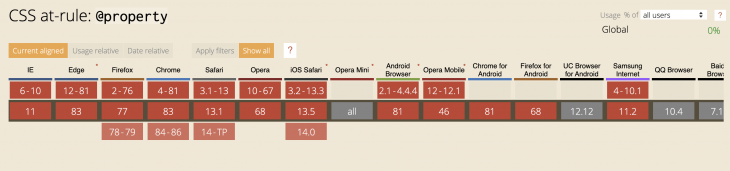

This experimental feature is still not implemented in any of the modern browsers and the conversation around its specifications is still going on. However, the idea behind it is promising and it seems like it can fix some of the previous CSS issues such as fading a gradient to a new color on hover or focus.

@property is nothing but a simplified version of CSS.registerProperty(). With these features, you can define the syntax for custom CSS properties. You can then use these properties under other selectors. For example, defining a custom CSS property called my-color using both the @property and CSS.registerProperty() looks something like this:

@property --my-color {

syntax: "<color>";

inherits: false;

initial-value: '#9400D3';

}

/

window.CSS.registerProperty({

name: '--my-color',

syntax: '<color>',

inherits: false,

initialValue: '#9400D3',

});

You can then use this custom property under other selectors:

// CSS

.mycolor {

--my-color: '#FFFFFF';

background: linear-gradient(var(--my-color), black);

transition: --my-color 1s;

}

..mycolor:hover {

--my-color: '#FF0000';

}

// HTML

<button class="mycolor">@property</button>

Examining this shows that the gradient of the button will change from the defined custom property --mycolor to '#FF0000' which is the red color. This is a much easier way of handling it compared to other ways of handling such scenarios with pseudo-elements.

However, until we get a wider range of browser support for this feature, it is a matter of various speculations on what would be the end functionality of this feature. Until then, feel free to test this as an experimental feature and keep an eye for its wider support in browsers.

Together, we have reviewed some of the most practical CSS rules out there. Almost any project that needs CSS can benefit from these rules, but make sure you understand the concepts behind them completely. Also, make sure to check the browser support for the rule that you want to use so you’re not surprised if the applied rule does not work in a specific browser.

Some of the rules are still in development for newer versions of CSS and you might need to use vendor prefixes before using them. Have a look at the list of current CSS at-rules here.

https://meiert.com/en/blog/css-at-rules/

https://css-tricks.com/the-at-rules-of-css/

https://css-tricks.com/snippets/css/using-font-face/

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/CSS/At-rule

As web frontends get increasingly complex, resource-greedy features demand more and more from the browser. If you’re interested in monitoring and tracking client-side CPU usage, memory usage, and more for all of your users in production, try LogRocket.

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork around why bugs happen by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings — compatible with all frameworks.

LogRocket's Galileo AI watches sessions for you, instantly identifying and explaining user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

Modernize how you debug web and mobile apps — start monitoring for free.

Compare the top AI development tools and models of March 2026. View updated rankings, feature breakdowns, and find the best fit for you.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the March 11th issue.

Buying AI tools isn’t enough. Engineering teams need AI literacy programs to unlock real productivity gains and avoid uneven adoption.

If your AI app or agent works perfectly in development but falls apart in production, you’re not alone. In a […]

Would you be interested in joining LogRocket's developer community?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now