satisfies operator

The TypeScript satisfies operator is one of the features released in TypeScript v4.9. It’s a new and better approach to type-safe configuration in TypeScript. The satisfies operator aims to give developers the ability to assign the most specific type to expressions for inference. In this article, we’ll take a closer look at the TypeScript satisfies operator and how to use the satisfies operator.

Jump ahead:

satisfies operator?

satisfies operator

satisfies operatorThe Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

satisfies operator?The satisfies operator is a feature in TypeScript that allows you to check if a given type satisfies a specific interface or condition. In other words, it ensures that a type has all the required properties and methods of a specific interface. It is a way to ensure a variable fits into a definition of a type. To learn more about types in TypeScript, visit our Types vs. interfaces in TypeScript guide.

satisfies operatorLet’s look at an example to understand why the TypeScript satisfies operator is intriguing and what problems it solves. Let’s create a type MyState that’s going to be a union of two properties, as shown below:

type MyState = StateName | StateCordinates;

Here, we are creating a type of MyState that will be StateName or StateCordinates. This means MyState is a union type that will be StateName or StateCordinates. Then, we’ll define our StateName as a string with three values. So, our StateName can be either Washington, Detroit, or New Jersey, as shown below:

type StateName = "Washington" | "Detriot" | "New Jersey";

The next step is to define our StateCordinates with the following code:

type StateCordinates = {

x: number;

y: number;

};

Our StateCordinate is an object that has two properties, x and y. The x and y properties are going to be numbers. Now, we have our type StateName (a string) and StateCordinates, (an object). Finally, let’s create our type User with the code below:

type User = {

birthState: MyState;

currentState: MyState;

};

Our type User has two properties, birthState and currentState. Both of these properties are of type MyState. This means that each of these properties can be a StateName or StateCoordinates. Next, we’re going to create a variable user using the code below:

const user:User = {

birthState: "Washington",

currentState: { x: 8, y: 7 },

};

In the code above, the user will have the birthState property set to the "Washington" string as one of the values for the StateName type. The CurrentState property is set to an object with property x with the value of 8 and property y of 7, corresponding to the StateCordinates.

So, this is a perfectly valid way to create and annotate the user variable. Imagine we want to access the birthState variable and convert it to uppercase, like so:

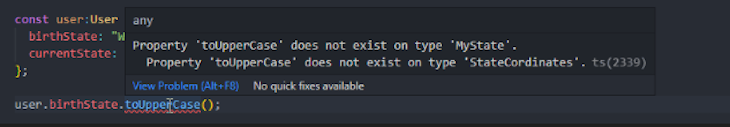

user.birthState.toUpperCase();

If we hover our mouse over toUpperCase(), TypeScript will throw in an error stating that "property toUpperCase() does not exist on type MyState and property to uppercase does not exist on type StateCordinates", as shown below:

This is because TypeScript is not sure of the value of MyState or whether it is a string or an object because we defined MyState as a union of a string and an object. Essentially, it can be any of them. In order to remove this error, we need to manually validate the property before we can use the string method, like so:

if (typeof user.birthState === "string") {

user.birthState.toUpperCase();

}

Here, we are writing a condition to check if it is a string, and if it is, then we can use the string method. Because we tested it as a string, the TypeScript error should disappear. Having to always validate whether it is a string can be frustrating and cumbersome. This is where the satisfies operator comes in.

satisfies operatorWhile life before the satisfies operator required you to always validate whether the property was a string or not, with the satisfies operator, you don’t have to do this. Instead of defining the user variable manually, we can delete it and replace it with the satisfies operator, like so:

const user = {

birthState: "Washington",

currentState: { x: 7, y: 8 },

} satisfies User;

user.birthState.toUpperCase();

The full code now looks like this:

type MyState = StateName | StateCordinates;

type StateName = "Washington" | "Detriot" | "New Jersey";

type StateCordinates = {

x: number;

y: number;

};

type User = {

birthState: MyState;

currentState: MyState;

};

const user = {

birthState: "Washington",

currentState: { x: 8, y: 7 },

} satisfies User;

user.birthState.toUpperCase();

The satisfies operator prevalidates all the object properties for us, and the TypeScript error no longer pops up. Now, the satisfies operator will validate our user properties for us. Not only that, but it will also check in advance if any of the properties contain a string or an object.

Thanks to the satisfies operator; TypeScript knows that our birthState is a string and not an object because it has prevalidated/checked the values of all properties of the User. And, if we try adding something else to the birthState property that doesn’t correspond to any of the defined types, we’ll get an error.

The satisfies keyword ensures that we only pass whatever satisfies the User type to the user variable, allowing TypeScript to do its type inference magic. Let’s look at some other examples.

We can also use the satisfies operator to tell the TypeScript compiler that it’s OK for an object to include only a subset of the given keys but not accept others. Here’s an example:

type Keys = 'FirstName' |"LastName"| "age"|"school"| "email"

const student = {

FirstName: "Temitope",

LastName: "Oyedele",

age: 36,

school:"oxford",

}satisfies Partial<Record<Keys, string | number>>;

student.FirstName.toLowerCase();

student.age.toFixed();

By using the satisfies operator in the code above, we instruct the TypeScript compiler that the type of the student object must match the PartialRecordKeys, string | number>> type. The Partial type in TypeScript is an inbuilt type that helps manipulate other user-defined types.

Similar to property name constraining, with the exception that in addition to restricting objects to only contain specific properties, we can also ensure that we get all of the keys using the satisfies operator. Here’s what that looks like:

type Keys = 'FirstName' |"LastName"| "age"|"school"

const student = {

FirstName: "Temitope",

LastName: "Oyedele",

age: 36,

school:"oxford",

}satisfies Record<Keys, string | number>;

student.age.toFixed();

student.school.toLowerCase();

Here, we use the satisfies operator with the Record<Keys, string | number> to check that an object has all the keys specified by the Keys type and has a value of either string or number type associated with each key.

The satisfies operator is not only capable of restricting the names of properties in an object, but it can also restrict the values of those properties. Suppose we have a library object with various books, each represented as an object with properties for the book’s title, author, and year of publication. However, we mistakenly used a string instead of a number for the year of publication of the book "Pride and Prejudice".

To catch this error, we can use the satisfies operator to ensure that all properties of the library object are of type Book, which we defined as an object with the required "title", "author", and "year" properties, where "year" is a number. Here’s what that looks like:

type Book = { title: string, author: string, year: number };

const library = {

book1: { title: "Things fall apart", author: "Chinua Achebe", year: 1958 },

book2: { title: "Lord of the flies", author: "William Golding", year: 1993 },

book3: { title: "Harry Potter", author: "J.k Rowling", year: "1997" }, // Error

} satisfies Record<string, Book>;

With the help of the satisfies operator, the TypeScript compiler can find the error and prompt us to correct the year property of the book "Harry Potter".

satisfies operatorThe satisfies operator allows us to improve the quality and scalability of our code. However, the satisfies operator’s main benefits are type safety, code correctness, validation, code reusability, and code organization.

The satisfies operator ensures that types have all the necessary methods and properties, ultimately reducing the likelihood of runtime problems. You may catch type problems at build time or before your code is run by using the satisfies operator.

We can use the satisfies operator to ensure the correctness of code because it allows us to check if a given type satisfies a particular condition.

The satisfies operator enables us to verify that an expression’s type matches another type without declaring a new variable or casting the expression to a different type.

Using the satisfies operator helps ensure that different parts of our application can consistently work with the same types of data. This helps to make code more modular and reusable.

Using the TypeScript satisfies operator helps organize your code into logical blocks based on the type of a value. This can help eliminate repeated type checks in various sections of your code and make it easier to read and comprehend.

The TypeScript satisfies operator is convenient and can help improve the quality and scalability of your code. It does the heavy lifting by prevalidating our values, giving us a more flexible and precise type-checking experience. We can also use the satisfies operator to create more robust and maintainable code.

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings — compatible with all frameworks, and with plugins to log additional context from Redux, Vuex, and @ngrx/store.

With Galileo AI, you can instantly identify and explain user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

Modernize how you understand your web and mobile apps — start monitoring for free.

Learn how to solve the LLM context problem with RAG, pruning, summarization, and tool loadouts for more reliable AI systems.

Discover five practical ways to scale knowledge sharing across engineering teams and reduce onboarding time, bottlenecks, and lost context.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the March 4th issue.

Paige, Jack, Paul, and Noel dig into the biggest shifts reshaping web development right now, from OpenClaw’s foundation move to AI-powered browsers and the growing mental load of agent-driven workflows.

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

One Reply to "Getting started with the TypeScript <code>satisfies</code> operator"

It was good that you took the original version of this article down following my critique of it, but sad to say, the new version is still very flawed. You still don’t fully understand the use of the satisfies operator, and indeed how TypeScript type inference works in general, though at least you now understand that satisfies is a compile-time feature, and has no relevance at run time.

The first example is a correct use of satisfies, but you totally misunderstand why; the second is contrived in a way that makes it LESS type safe than it should be (and once that’s corrected, is a really weak argument for using satisfies anyway), and the third and fourth examples simply don’t require satisfies at all.

In example 1, you say:

“Thanks to the satisfies operator;[sic] TypeScript knows that our birthState is a string and not an object because it has prevalidated/checked the values of all properties of the User.”

No, satisfies is NOT the reason the compiler knows the type of birthState! The code compiles because you removed the type from the variable, allowing the compiler to infer the type of the object from the values used in its creation. The compiler knows that user.birthState is a string because it just saw it being initialized! You can remove the satisfies clause (and indeed the type User), and the code will still compile. If you think about, all you’re saying with the satisfies is that birthState must be a MyState, so it will catch errors like giving birthState a numeric value, but that has nothing to do with why your example compiles.

The second example is valid, but its contrived nature means you’re actually ending up with LESS type safety than with how you’d typically write this code. By using the Record type, you’re preventing the compiler from doing the obvious checks on the properties. A correct version of this example would be:

type Student = { FirstName: string; LastName: string; age: number; school: string; email: string };

const student = {

FirstName: “Temitope”,

LastName: “Oyedele”,

age: 36,

school: “oxford”,

} satisfies Partial;

student.FirstName.toLowerCase();

student.age.toFixed();

Here, you get the benefit of type checking on the individual properties, with your desire to allow a partial definition. In your original, you unnecessarily hamper the compiler’s ability to check your code.

Once you get rid of the Record, it’s also not obvious to me that using satisfies gains you anything over the more idiomatic convention of making email an optional property, because Partial is really TOO permissive in most cases:

type Student = { FirstName: string; LastName: string; age: number; school: string; email?: string };

const student: Student = {

FirstName: “Temitope”,

LastName: “Oyedele”,

age: 36,

school: “oxford”,

};

There’s a similar but greater problem with the third example. You’re again losing the type checking on the individual properties, while gaining nothing from using satisfies. In practice, you’d write this example:

type Student = { FirstName: string; LastName: string; age: number; school: string };

const student: Student = {

FirstName: “Temitope”,

LastName: “Oyedele”,

age: 36,

school: “oxford”,

};

student.age.toFixed();

student.school.toLowerCase();

That will allow the compiler to flag extra or missing properties, or type errors on the properties themselves, with no need for satisfies at all.

Just for completeness’ sake, the fourth example is also a non-use case for satisfies. It does nothing that this long-correct code wouldn’t achieve:

type Book = { title: string, author: string, year: number };

const library: Record = {

book1: { title: “Things fall apart”, author: “Chinua Achebe”, year: 1958 },

book2: { title: “Lord of the flies”, author: “William Golding”, year: 1993 },

book3: { title: “Harry Potter”, author: “J.k Rowling”, year: “1997” }, // Error

};

I think the best way to summarize the *correct* use of satisfies is that it gives a degree of type-checking on an object, without removing the specific type inference that allows the compiler to validate later operations on it. At best, your examples and the explanations of them only partially reflect this.

On a more general note, the article again shows a lack of attention to detail: inconsistency in the use of ‘ vs. ” for strings, inconsistency in the case of property names, a typo in “Detroit”. You should install one of the popular lint tools, and perhaps use an IDE that includes a spell checker, such as WebStorm.