Web workers provide a way to run JavaScript code outside the single thread of execution in the browser. The single thread handles requests to display content as well as user interactions via keyboard, mouse clicks, and other devices, and also responses to AJAX requests.

Event handling and AJAX requests are asynchronous and can be considered a way to run some code outside the code path of general browser display, but they still run in this single thread and really have to finish fairly quickly.

Otherwise, interactivity in the browser stalls.

Web workers allow JavaScript code to run in a separate thread, entirely independent of the browser thread and its usual activities.

There’s been a lot of debate in recent years about what use there really is for web workers. CPUs are very fast these days, and almost everyone’s personal computer comes out of the box with several gigabytes of memory. Similarly, mobile devices have been approaching both the processor speed and memory size of desktop machines.

Applications that might once have been considered “computationally intensive” are now considered not so bad.

But many times we consider only the execution of the one application, tested in the development environment, when deciding how to execute code efficiently. In a real-life system in the hands of a user, many things may be executing at once.

So applications that, running in isolation, might not have to use worker threads may have a valid need to use them to provide the best experience for a wide range of users.

Starting a new worker is as simple as specifying a file containing JavaScript code:

new Worker(‘worker-script.js’)

Once the worker is created, it is running in a separate thread independent of the main browser thread, executing whatever code is in the script that is given to it. The browser looks relative to the location of the current HTML page for the specified JavaScript file.

Data is passed between Workers and the main JavaScript thread using two complementary features in JavaScript code:

postMessage() function on the sending sideThe message event handler receives an event argument, as other event handlers do; this event has a “data” property that has whatever data was passed from the other side.

This can be a two-way communication: the code in the main thread can call postMessage() to send a message to the worker, and the worker can send messages back to the main thread using an implementation of the postMessage() function that is available globally in the worker’s environment.

A very simple flow in a web worker would look like this: in the HTML of the page, a message is sent to the worker, and the page waits for a response:

var worker = new Worker("demo1-hello-world.js");

// Receive messages from postMessage() calls in the Worker

worker.onmessage = (evt) => {

console.log("Message posted from webworker: " + evt.data);

}

// Pass data to the WebWorker

worker.postMessage({data: "123456789"});

The worker code waits for a message:

// demo1-hello-world.js

postMessage('Worker running');

onmessage = (evt) => {

postMessage("Worker received data: " + JSON.stringify(evt.data));

};

The above code will print this to the console:

Message posted from webworker: Worker running

Message posted from webworker: Worker received data: {“data”:”123456789"}

Multiple messages can be sent and received between browser and worker during the life of a worker.

The implementation of web workers ensures safe, conflict-free execution in two ways:

postMessage() callEach worker thread has a distinct, isolated global environment that is different from the JavaScript environment of the browser page. Workers are not given any access at all to anything in the JavaScript environment of the page — not the DOM, nor the window or document objects.

Workers have their own versions of some things, like the console object for logging messages to the developer’s console, as well as the XMLHttpRequest object for making AJAX requests. But other than that, the JavaScript code that runs in a worker is expected to be self-contained; any output from the worker thread that the main window would want to use has to be passed back as data via the postMessage() function.

Furthermore, any data that is passed via postMessage() is copied before it is passed, so changing the data in the main window thread does not result in changes to the data in the worker thread. This provides inherent protection from conflicting concurrent changes to data that’s passed between main thread and worker thread.

The typical use case for a web worker is any task that might become computationally expensive in the course of its execution, either by consuming a lot of CPU time or taking an unpredictably long amount of clock time to access data.

Some possible use cases for web workers:

CPU time is the simple use case, but network access to resources can also be very important. Many times network communication over the internet can execute in milliseconds, but sometimes a network resource becomes unavailable, stalling until the network is restored or the request times out (which can take 1–2 minutes to clear).

And even if some code might not take very long to run when tested in isolation in the development environment, it could become an issue running in a user’s environment when multiple things could be running at the same time.

The following examples demonstrate a couple of ways that web workers can be used.

(Strap in. This is a long example.)

HTML5-based games that execute in the web browser are everywhere now. One central aspect of games is computing motion and interaction between parts of the game environment. Some games have a relatively small number of moving parts and are fairly easy to animate (Super Mario emulator clone, anyone?). But let’s consider a more computationally heavy case.

This example involves a large number of colored balls bouncing in a rectangular boundary. The goal is to keep the balls within the borders of the game, and also to detect collisions between balls and make them bounce off each other.

Bounds detection is relatively simple and fast to execute, but collision detection can be more computationally demanding, since it grows roughly as the square of the number of balls — for “n” balls, each ball has to be compared to each other ball to see if their paths have intersected and need to be bounced (resulting in n times n, or n squared comparisons).

So for 50 balls, on the order of 2,500 checks have to be made; for 100 balls, 10,000 checks are needed (it’s actually slightly less than half that amount: if you check ball n against ball m, you don’t have to later check ball m against ball n, but still, there can be a large number of computations involved).

For this example, the bounds and collision detection is done in a separate worker thread, and that thread executes at browser animation speed, 60 times a second (every call to requestAnimationFrame()). A World object is defined which keeps a list of Ball objects; each Ball object knows its current position and velocity (as well as radius and color, to allow it to be drawn).

Drawing the balls at their current positions happens in the main browser thread (which has access to the canvas and its drawing context); updating the position of the balls happens in the worker thread. The velocity (specifically the direction of movement of the balls) is updated if they hit the game boundary or collide with another ball.

The World object is passed between the client code in the browser and the worker thread. This is a relatively small object even for just a few hundred balls (100 times roughly 64 bytes of data per ball = 6,400 bytes of data). So the issue here is computational load.

The full code for this example can be found in the CodePen here. There’s a Ball class to represent the objects being animated and a World class that implements move() and draw() methods that does the animation.

If we were doing straight animation without using a worker, the main code would look something like this:

const canvas = $('#democanvas').get(0),

canvasBounds = {'left': 0, 'right': canvas.width,

'top': 0, 'bottom': canvas.height},

ctx = canvas.getContext('2d');

const numberOfBalls = 150,

ballRadius = 15,

maxVelocity = 10;

// Create the World

const world = new World(canvasBounds), '#FFFF00', '#FF00FF', '#00FFFF'];

// Add Ball objects to the World

for(let i=0; i < numberOfBalls; i++) {

world.addObject(new Ball(ballRadius, colors[i % colors.length])

.setRandomLocation(canvasBounds)

.setRandomVelocity(maxVelocity));

}

...

// The animation loop

function animationStep() {

world.move();

world.draw(ctx);

requestAnimationFrame(animationStep);

}

animationStep();

The code uses requestAnimationFrame() to run the animationStep() function 60 times a second, within the refresh period of the display. The animation step consists of the move, updating the position of each of the balls (and possibly the direction), then the draw, redrawing the canvas with the balls in their new position.

To use a worker thread for this application, the move portion of the game animation loop (the code in World.move()) will be moved to the worker. The World object will be passed as data into the worker thread via the postMessage() call so that the move() call can be made there. The World object is clearly the thing to be passed around, since it has the display list of Balls and the rectangular boundary that they’re supposed to stay within, and each ball retains all the information about its position and velocity.

With the changes to use the worker, the revised animation loop looks like this:

let worker = new Worker('collider-worker.js');

// Watch for the draw event

worker.addEventListener("message", (evt) => {

if ( evt.data.message === "draw") {

world = evt.data.world;

world.draw(ctx);

requestAnimationFrame(animationStep);

}

});

// The animation loop

function animationStep() {

worker.postMessage(world); // world.move() in worker

}

animationStep();

And the worker thread itself simply looks like this:

// collider-worker.js

importScripts("collider.js");

this.addEventListener("message", function(evt) {

var world = evt.data;

world.move();

// Tell the main thread to update display

this.postMessage({message: "draw", world: world});

});

The code here relies on the worker thread to accept the World object in the postMessage() from the main code and then pass the world back to the main code with positions and velocities updated.

Remember that the browser will make a copy of the World object as it’s passed in and out of the worker thread — the assumption here is that the time to make a copy of the World object is significantly less than the O(n**2) collision computations (it’s really a relatively small about of data that’s kept in the World).

Running the new worker thread based code results in an unexpected error, however:

Uncaught TypeError: world.move is not a function at collider-worker.js:10

It turns out that the process of copying an object in the postMessage() call will copy the data properties on the object, but not the prototype of the object. The methods of the World object are stripped from the prototype when it’s copied and passed to the worker. This is part of the “Structured Clone Algorithm”, the standard way that objects are copied between main thread and web worker, also known as serialization.

To work around this, I’ll add a method to the World class to create a new instance of itself (which will have the prototype with the methods) and reassign the data properties from the data passed that’s posted in the message:

static restoreFromData(data) {

// Restore from data that's been serialized to a worker thread

let world = new World(data.bounds);

world.displayList = data.displayList;

return world;

}

Trying to run the animation with this fix results in another, similar error… The underlying Ball objects within the World’s display list also have to be restored:

Uncaught TypeError: obj1.getRadius is not a function at World.checkForCollisions (collider.js:60) at World.move (collider.js:36)

The implementation of the World class has to be enhanced to restore each Ball in its display list from data, as well as the World class itself.

Now, in the World class:

static restoreFromData(data) {

// Restore from data that's been serialized to a worker thread

let world = new World(data.bounds);

world.animationStep = data.animationStep;

world.displayList = [];

data.displayList.forEach((obj) => {

// Restore each Ball object as well

let ball = Ball.restoreFromData(obj);

world.displayList.push(ball);

});

return world;

}

And a similar restoreFromData() method implemented in the Ball class:

static restoreFromData(data) {

// Restore from data that's been serialized to a worker thread

const ball = new Ball(data.radius, data.color);

ball.position = data.position;

ball.velocity = data.velocity;

return ball;

}

With this, the animation runs correctly, computing the moves of each of possibly hundreds of balls in the worker thread and displaying their updated positions at 60 times per second in the browser.

This example of worker threads is compute-bound but not memory-bound. What about a case where memory can also be an issue?

For the final example, let’s look at an application that is both CPU and memory intensive: getting the pixels in an HTML5 canvas image and transform them, producing and displaying another image.

This demonstration will use an image processing library written in 2012 by Ilmari Heikkinen. It will take a color image and convert it to a binary black-and-white image, thresholded at an intermediate gray value: pixels whose grayscale value is less than this value appear black; greater than that value appear white.

The thresholding code steps through each (rgb) value, using a formula to transform it into a gray value:

Filters.threshold = function(pixels, threshold) {

var d = pixels.data;

for (var i=0; i < d.length; i+=4) {

var r = d[i];

var g = d[i+1];

var b = d[i+2];

var v = (0.2126*r + 0.7152*g + 0.0722*b >= threshold) ? 255 : 0;

d[i] = d[i+1] = d[i+2] = v

}

return pixels;

};

For an image that initially looks like this:

The thresholding algorithm produces a two-tone black-and-white image like this:

The CodePen for this demo can be found here.

Even for small images the data, as well as the computation involved, can be large. A 640×480 image has 307,200 pixels, each of which has four bytes of RGBA data (“A” standing for alpha, or transparency data), bringing the size of the image data to 1.2MB. The plan is to use a web worker to iterate over each of the pixels and transform them to new RGB values. The pixel data for the image is to be passed from the browser to the worker thread, and a modified image would be returned back. It would be better not to have this data copied each time it’s passed back and forth between client and worker thread.

An extension to the postMessage() call provides a way to specify one or more properties of the data that is passed with the message that is supposed to be passed by reference instead of being copied. It looks like this:

<div style="margin: 50px 100px">

<img id="original" src="images/flmansion.jpg" width="500" height="375">

<canvas id="output" width="500" height="375" style="border: 1px solid;"></canvas>

</div>

...

<script type="text/javascript">

const image = document.getElementById('original');

...

// Use a temporary HTML5 canvas object to extract the image data

const tempCanvas = document.createElement('canvas'),

tempCtx = tempCanvas.getContext('2d');

tempCanvas.width = image.width;

tempCanvas.height = image.height;

tempCtx.drawImage(image, 0, 0, image.width, image.height);

const imageDataObj = tempCtx.getImageData(0, 0, image.width, image.height);

...

worker.addEventListener('message', (evt) => {

console.log("Received data back from worker");

const results = evt.data;

ctx.putImageData(results.newImageObj, 0, 0);

});

worker.postMessage(imageDataObj, [imageDataObj.data.buffer]);

</script>

Any object that implements the Transferable interface can be specified here. The data.buffer of an ImageData object meets this requirement — it’s of type Uint8ClampedArray (an array type intended for storing 8-bit image data). ImageData is what is returned by the getImageData() method of the HTML5 canvas context object.

In general several standard data types implement the Transferable interface: ArrayBuffer, MessagePort, and ImageBitmap. ArrayBuffer is in turn implemented by a number of specific array types: Int8Array, Uint8Array, Uint8ClampedArray, Int16Array, Uint16Array, Int32Array, Uint32Array, Float32Array, Float64Array.

So if data is now being passed between threads by reference and not by value, could the data be modified in both threads at once? The standards prevent this: when data is passed by postMessage(), access to the data is disabled (the term “neutered” is actually used in the specs) on the sending side, making it unavailable. Passing the data back again via postMessage() “neuters” it on the worker thread side, but makes it accessible back in the browser. This “neutering” feature is implemented in the JavaScript engine.

HTML5 web workers provide a way to offload heavy computation to a separate thread of execution that won’t stall the main event thread of the browser.

Two examples demonstrated some of the features of web workers:

postMessage() calls and message event listenerspostMessage() functionAlong the way, the examples demonstrated explored several issues and implementation details of web workers:

postMessage() does not copy the methods in the prototype of the object — some code has to be contrived to restore thesegetImageData() method, the buffer property of the pixel data object has to be passed to the postMessage() call (like imageData.data.buffer, not imageData.data). It’s the buffer that implements TransferableWeb workers are currently supported by most of the major, current browsers. Chrome, Safari, and Firefox have supported them since about 2009; they’re supported on MSEdge and have been supported on Internet Explorer since IE10.

For compatibility with browsers, a simple check for if (typeof Worker !== "undefined") could protect the code that creates and uses the worker, with an alternative execution of the same code outside the worker (in a timeout or an animation frame).

Debugging code is always a tedious task. But the more you understand your errors, the easier it is to fix them.

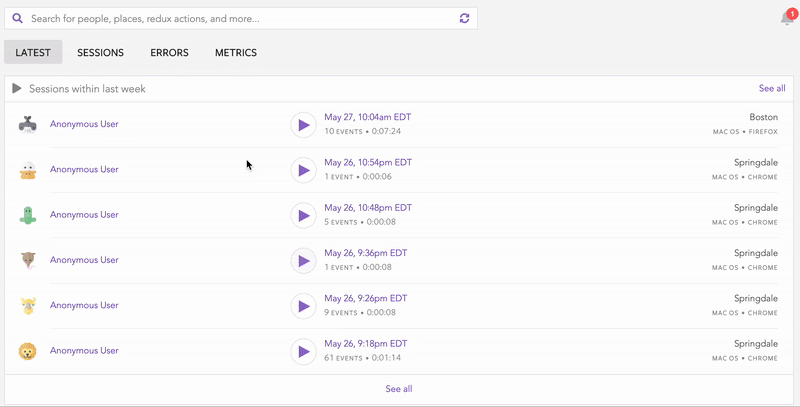

LogRocket allows you to understand these errors in new and unique ways. Our frontend monitoring solution tracks user engagement with your JavaScript frontends to give you the ability to see exactly what the user did that led to an error.

LogRocket records console logs, page load times, stack traces, slow network requests/responses with headers + bodies, browser metadata, and custom logs. Understanding the impact of your JavaScript code will never be easier!

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

Learn how OpenAPI can automate API client generation to save time, reduce bugs, and streamline how your frontend app talks to backend APIs.

Discover how the Interface Segregation Principle (ISP) keeps your code lean, modular, and maintainable using real-world analogies and practical examples.

<selectedcontent> element improves dropdowns

Learn how to implement an advanced caching layer in a Node.js app using Valkey, a high-performance, Redis-compatible in-memory datastore.

3 Replies to "Using web workers for safe, concurrent JavaScript"

Cool, thanks

great examples, great read.

Can I transfer objects between a worker thread and a main thread? For example, an html div that hosts a chart?