Strongly typed and statically typed languages are related programming concepts, particularly in frontend development. However, they’re also quite different and have distinct advantages and disadvantages. Although both categories enforce type safety, strongly typed languages enhance type safety further by ensuring that variables are used consistently with their defined types.

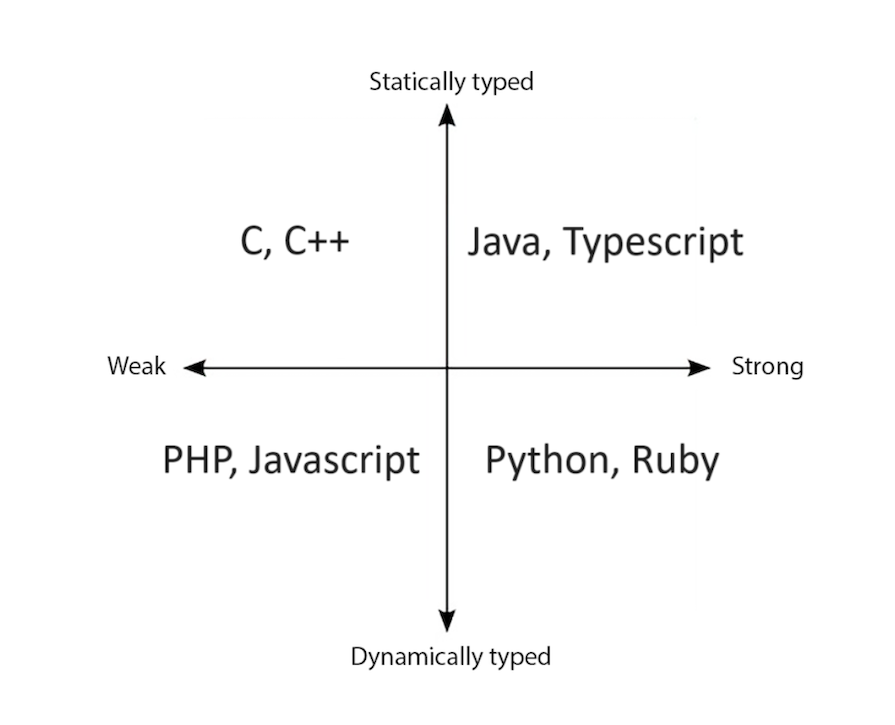

It’s important to note that a language could belong to both categories or neither. In a much broader sense, languages typically fall in one quadrant of an axis chart where one axis contains statically typed and dynamically typed languages, and the other contains strongly and weakly typed languages:

So, a language could be:

It’s also important to note that “weak” and “strong” don’t have universally agreed-upon definitions. Generally, the terms “weak” and “strong” refer to the strictness of the type rules.

It makes much more sense to use these terms in a relative sense. For example, you could say that Java is more strongly typed than C or that C is more strongly typed than JavaScript.

Let’s look at what these concepts are about in further detail. You can also check out this GitHub repo to explore the code samples in this guide.

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

In statically typed languages, you need to explicitly specify the data type of variables when you declare them. This means that the type-checking process occurs during the compilation phase, in contrast to dynamically typed languages where type-checking happens during runtime.

The script or code cannot be compiled if there are type mismatches. This leads to more reliable and predictable code by detecting errors early in development.

C is a statically typed language, as the type associated with every variable must be explicitly mentioned. For example:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int a = 5; // variable of int type

float c = 9.000; // variable of float type

}

Statically typed languages like C expect variable declarations before they can be used.

Let’s take a look at a piece of dynamically typed Python code to compare:

example = 3 exmple = example + 9 // a typo print(example)

In the example above, the variable example is initialized with a value of 3. In the next line, there’s a typo where the variable exmple is assigned another value.

Since Python is dynamically typed, it treats exmple as a new variable and doesn’t throw any errors. This could lead to problems in the code if the programmer wanted to access the value of example again and expected an updated value.

Dynamically typed languages like Python and JavaScript offer more flexibility, but they might lead to runtime errors due to unexpected type mismatches. On the other hand, statically typed languages are more verbose, which developers might sometimes find inconvenient, especially when rapid prototyping is required.

In some cases, statically typed languages might also use more boilerplate code. This could be daunting for new developers, especially those coming from a dynamically typed language background.

Another major area where statically typed languages shine is IDEs — they usually have robust development environments. The predictability of statically typed languages also offers benefits such as code completion, better refactoring, and more.

Strongly typed languages have strict type rules— they usually enforce strict adherence to types. There is no widely agreed-upon meaning of the terms “strongly” and “weakly” typed languages, making it somewhat harder to classify a language as belonging to either.

It makes much more sense to talk relatively about which languages provide better type safety. Generally speaking, JavaScript and C are both considered weakly typed languages. However, C is more strongly typed than JavaScript and many others.

Take a look at this example in C:

int variable1 = 10; // In C, variable1 can not hold an array, for example

Here’s the same example in JavaScript:

let variable1 = 10; // In javascript though, we could assign an array to variable1 variable1 = []; // no errors

While C has a stronger type system, it also provides ways to bypass this system, which many programmers might consider a weakly typed feature. Take a look at this C code, which allows us to bypass strict typing using casts:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int a = 17;

float b = 21.5;

void *ptr;

ptr = &a;

printf("Value of a: %d\n", *(int *)ptr); // Casting void* to int*

ptr = &b;

printf("Value of b: %f\n", *(float *)ptr); // Casting void* to float*

return 0;

}

In this code, we’re using a void* pointer (ptr) to store the addresses of both an int and a float variable. This demonstrates weak typing because the void* pointer can hold any type of data, and the actual data type being pointed to is interpreted at runtime.

However, it’s safe to say that the C code above is more strongly typed than JavaScript.

Let’s recap what we’ve learned about strongly typed and statically typed languages:

| Strongly typed languages | Statically typed languages | |

|---|---|---|

| Use | Enforce strict type rules | Require you to specify a variable’s data type when declaring the variable. Type-checking occurs during compilation |

| Benefits | Reduce the chances of runtime errors related to type mismatches; increase readability and predictability of code and better optimization in some cases; have better IDE support | Errors are easier to detect early on in development; better IDE support, readability and predictability of code |

| Drawbacks | Generally have a steeper learning curve; increase code duplication | Tend to be verbose and use more boilerplate code, which can be inconvenient for rapid development and daunting for new developers |

While there is a lot of overlap between the two categories, this summary table should help you better understand the advantages of differently typed languages and any considerations to keep in mind while using them.

TypeScript is a statically typed language that also provides a strong type system. Due to this balance of strong and static typing, it has gained significant importance in the frontend development ecosystem.

In addition, TypeScript’s excellent IDE support makes it convenient to work with while providing a tight type safety net around JavaScript. It’s an especially valuable option for large-scale projects.

Consider the JavaScript code below:

function add(a, b) {

return "$" + a + b; // No type checking

}

add('5' + '6') // $56undefined

Here’s the same code in TypeScript:

add(a : number, b: number) {

return "$" + (a + b).toString();

}

add('5', '6'); // Type string is not assignable to type number

With its strong type system, TypeScript can point out potential bugs during compilation, as shown in the code examples above. Note that there are also methods for runtime type-checking in TypeScript.

Additionally, keep in mind that TypeScript can also exhibit weak typing in certain scenarios, mainly when performing type assertions or dealing with any types. Consider this example:

let x: number = 5; let y: any = "10"; x = y; // No error, despite y being of type 'any' console.log(x); // Outputs: "10"

TypeScript here shows a bit of weak typing behavior by allowing you to assign a value with a different type (any) to a variable with a more specific type (number). This scenario bypasses TypeScript’s type checks due to the any type, potentially leading to runtime errors if the assigned type is incompatible.

TypeScript provides several ways to perform type casting or type assertions when working with different data types. For example:

let value: any = "Hello"; let length: number = (<string>value).length;

However, using any is just a way to bypass TypeScript’s strict type checker. This also depends on the programmer’s comfort with types and allows for a more lenient approach similar to JavaScript.

Overall, TypeScript aims to enhance type safety and catch potential errors at compile time. While weak typing scenarios are possible, the language encourages and promotes strong typing practices to minimize such cases and ensure better code reliability.

Consider another real-world scenario:

class Person extends Animal {

speak() {

}

}

class Dog extends Animal {

bark() {

}

}

Here, we have two classes that extend the same base class of Animal, but they have different methods in them. In large projects — especially in the event-driven JavaScript ecosystem — cases like this are common, where an object performs an action when it’s passed to a method:

function test(a: Dog) {

a.bark();

}

This makes sure that whenever this function is called, an object of Dog is passed. You can make the type rules quite strict in your application.

To provide a little more flexibility while still keeping the typing strong, TypeScript has union types, which offer a way to express that a variable or parameter can have different types at different times. The syntax for creating a union type is the use of the pipe | character between the types.

JavaScript methods like find could return undefined, so it’s convenient to use union types in cases like this. Consider how the example above would work with a union type instead:

function test(a: Dog | Person) {

a.speak(); // compilation error - speak doesn't exist on type Dog

}

TypeScript does not allow you to call the speak method, as it’s not present in Dog. However, it allows you to work around this just as you would in JavaScript. Based on the structure of the code, TypeScript can deduce a more specific type for a value. As a result, something like this will work:

function test(a: Person | Dog) {

if (a instanceof Person) {

a.speak() // speak if it is a person

} else {

a.bark(); // bark if it is a dog

}

}

Features like the any keyword and type assertions also come in handy, especially when dealing with complicated structures where it’s hard to come up with type definitions or when TypeScript wouldn’t know about the type itself. For example:

interface ApiResponse {

id: number;

name: string;

// other properties...

}

// simulated API response (may come from an actual API call)

const response: any = {

id: 1,

name: "",

// other properties may or may not be present in the actual response

};

// using type assertion to inform TypeScript about the response structure

const safeResponse = response as ApiResponse;

The inference feature we saw in the previous example is similar to the flexibility found in weakly typed languages like JavaScript, where types are automatically determined at runtime. TypeScript’s type inference helps reduce the need for explicit type annotations and allows for more flexibility when needed.

In this way, TypeScript allows developers to slowly introduce types into existing JavaScript codebases. You can start with minimal typing and progressively add more as needed. This provides a smooth transition from weakly typed JavaScript to a more strongly typed TypeScript codebase.

Strongly typed and statically typed languages each come with distinct advantages and disadvantages. Since the two categories often overlap, it can make more sense to compare languages based on when the type check happens and whether the languages enforce type declaration so that the type inconsistencies are caught during compilation.

Statically typed languages such as C require you to explicitly declare variable types during compilation, which helps you ensure that you detect errors early and develop robust code. While this approach may be considered more verbose, it contributes to better IDE support and predictability.

TypeScript stands out as a language that successfully combines the benefits of both strong and static typing. Despite some instances of weak typing, TypeScript’s emphasis on type safety fosters better code reliability and maintainability.

I hope you found this guide to strongly typed vs. statically typed code helpful! If you have any further questions, feel free to comment them below. You can also explore the code samples used throughout this article in this GitHub repo.

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings — compatible with all frameworks, and with plugins to log additional context from Redux, Vuex, and @ngrx/store.

With Galileo AI, you can instantly identify and explain user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

Modernize how you understand your web and mobile apps — start monitoring for free.

Signal Forms in Angular 21 replace FormGroup pain and ControlValueAccessor complexity with a cleaner, reactive model built on signals.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the February 25th issue.

Explore how the Universal Commerce Protocol (UCP) allows AI agents to connect with merchants, handle checkout sessions, and securely process payments in real-world e-commerce flows.

React Server Components and the Next.js App Router enable streaming and smaller client bundles, but only when used correctly. This article explores six common mistakes that block streaming, bloat hydration, and create stale UI in production.

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

One Reply to "Using strongly typed vs. statically typed code"

in C you can absolutely put an array inside an int variable, i can say more, you can put an int array inside a char variable, JavaScript is dynamically typed but doesn’t allow types to collide without explicit conversion, so you can never force the data of an array to become something else, every operator that converts types in Javascript has a well established result that is type safe, the problem of javascript is that those established conversion don’t always make sense, and that confuses people, but you could never interpret a type of data as it was of a different type (like you can in C).

for example in C you can define a char variable, assign an integer value to it and when you try to print it it will implicitly interpret that value as a character, that is as type unsafe as you can be, maybe only assembly or machine code can be more type unsafe than this.