Drag and drop features have existed for many years.

Since the advent of jQuery and DOM manipulation, it’s gotten a lot easier to make things draggable and create places that can be droppable for them.

Nowadays, companies like Gmail, Dropbox, and Microsoft seem to be keen on using this well-established feature by utilizing tons of different libraries and techniques to achieve a variety of effects.

They also utilizing drag and drop features to allow their users to upload files.

It goes even beyond that to the point where UI/UX professionals can measure when this effect is needed based on their user’s preferences and behaviors.

When it comes to React, three main libraries seem to have embraced this world:

In this article, we’ll run away from the common usage of this lib, which is for file uploading or features alike.

Instead, we’ll develop a game: the famous Tower of Hanoi.

This is how it’ll look when we’re done:

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

If you’re not familiar with the puzzle, the Tower of Hanoi is a classic game played and developed by many students from Computer Science when first starting to learn how to program, especially because it’s easy to code.

The game consists of three or more disks or tiles stacked on top of each other in one initial tower.

They start stacked from the largest to the smallest disk. You can remove them and drag them to another tower.

These are the rules:

The goal is to move the whole pile of disks from one tower to another in the fewest moves possible.

The documentation of react-dnd is very simple and easy to follow.

Before we proceed to the coding, we need first to understand some key concepts.

They’re the API under the abstraction of using drag and drop.

We have a common interface with functions that can be rewritten in any type of device, depending on which has implemented the abstraction.

For this tutorial, we’ll take advantage of the HTML5 drag and drop API as the backend for our game app.

Dragging and dropping things is inherently connected to maintaining a state.

In other words, every time you drag a component from one place to another, you’re actually moving data around. Data needs to be saved in a state.

The monitors are the wrappers of that state, allowing you to recover and manage your component’s data as a result of dragging and dropping over the component.

As the name suggests, we need something to connect both worlds: the React components and the DOM nodes that are, actually, performing the physical drag-and-drop operations.

It tells which, in the end, is a valid drag element or a drop target.

You’ll see soon that those are also the respective React component names for the dragging and dropping decorators.

They represent the primary abstraction of the APIs we’ve talked about, injecting the values and performing the callback operations of drag and drop.

All of that logic needs to be encapsulated into higher components — the ones that represent logical divisions to you and your React architecture.

The high-order components take what they need to concatenate all the react-dnd operations of dragging and dropping and return a new component recognizable by the lib.

In other words, it’s the component class we’ll create that annotates the DnD logic and returns a valid DnD component.

In order to follow through with this tutorial, you’ll need to have Node, npm, and npx properly installed and working on your machine. Go ahead and do that if you haven’t already.

We’re also going to use Yarn as the package manager since it is simple and straightforward. Make sure you have the latest version.

We’re going to make use of create-react-app for scaffolding our application and facilitating the initial configurations.

In the directory of your choice, run the following command:

npx create-react-app logrocket-hanoi-tower cd logrocket-hanoi-tower yarn start

This will start the default application and open it in your browser.

Next, we need to add the react-dnd dependencies to our project.

To do that, run the following command into the root folder:

yarn add styled-components react-dnd react-dnd-html5-backend

Note that we’re adding two other dependencies:

react-dnd for web browsers (not supported in mobile devices yet)Now we’re going to look at the code.

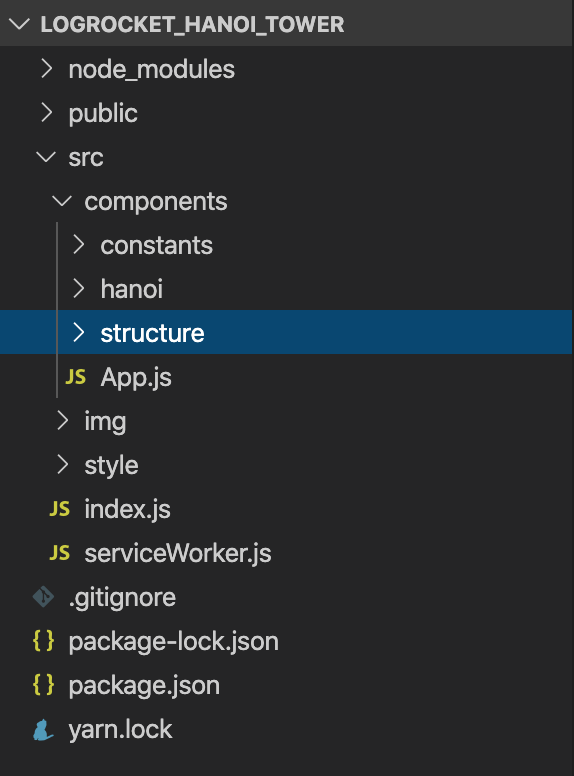

But first, let me show the project architecture:

We basically have three main folders. The first is for the components and the constants we’ll need to store data such as the heights of the tiles and towers, etc.

The second folder will hold the images, and the third will contain the styles. We also still have a CSS file for the body and general styling.

Let’s start with the constants since we’ll need them in the rest of the code.

Create a new JavaScript file called Constants.js and add the following code:

const NUM_TILES = 3;

const TOWER_WIDTH = `${30 * NUM_TILES}px`;

const HEADER_HEIGHT = "8rem";

const FOOTER_HEIGHT = "2rem";

const HANOI_HEIGHT = `(100vh - ${HEADER_HEIGHT} - ${FOOTER_HEIGHT})`;

const TOWER_HEIGHT = `(${TOWER_WIDTH} * ${NUM_TILES}) * 1.3`;

const TILE_HEIGHT = `(${TOWER_HEIGHT} / 12)`;

const getWidth = () => {

switch (NUM_TILES) {

case 1:

return 13;

case 2:

return 10.5;

case 3:

return 8;

default:

return 3;

}

};

const TILE_WIDTH_BASE = getWidth();

export default {

TOWER_WIDTH,

HEADER_HEIGHT,

FOOTER_HEIGHT,

HANOI_HEIGHT,

TOWER_HEIGHT,

TILE_HEIGHT,

TILE_WIDTH_BASE,

NUM_TILES

};

There’s a lot here, but don’t be fooled: it’s just constants to set up the default and/or auto-generated values of heights, widths, and the number of tiles we’ll have.

Since the browser page will be our game background and each monitor has different dimensions, we need to calculate in real-time where each component will be placed — especially in the case of re-dimensioning and responsive responses.

For the sake of simplicity, our game will only have a maximum 3 tiles.

However, you can change this constant at any time and see how the game behaves with added difficulty.

The second JavaScript file is called Types.js. This file will simply store the types of elements we have in the scene.

Right now, that just means the tile:

export const TILE = "tile"

The next two components are strategic — mainly because of their names.

Now, we need both a tower and a tile. Let’s start with Tile.js:

import React, { Component } from "react";

import { DragSource } from "react-dnd";

import Constants from "../constants/Constants";

import { TILE } from "../constants/Types";

const tile = {

beginDrag({ position }) {

return { position };

}

};

const collect = (connect, monitor) => ({

dragSource: connect.dragSource(),

dragPreview: connect.dragPreview(),

isDragging: monitor.isDragging()

});

class Tile extends Component {

render() {

const { position, dragSource, isDragging } = this.props;

const display = isDragging ? "none" : "block";

const opacity = isDragging ? 0.5 : 1;

const width = `(${Constants.TOWER_WIDTH} + ${position * 100}px)`;

const offset = `${(position * Constants.TILE_WIDTH_BASE) / 2}vw`;

const tileStyle = {

display: display,

opacity: opacity,

height: "60px",

width: `calc(${width})`,

transform: `translateX(calc(${offset} * -1))`,

border: "4px solid white",

borderRadius: "10px",

background: "#764abc"

};

return dragSource(<div style={tileStyle} position={position} />);

}

}

export default DragSource(TILE, tile, collect)(Tile);

Tile is the first high-order component that represents our drag element (DragSource). We drag tiles into towers.

Note that by the end of the code, our DragSource declaration needs some arguments:

beginDrag: the only required function, which returns the data describing the dragged itemendDrag: an optional function, which is called at the end of the drag operationThe rest of the implementation is style-related. It applies our CSS style to the tile component.

Now let’s get to our Tower.js code. Place the following to the file:

import React, { Component } from "react";

import { DropTarget } from "react-dnd";

import Tile from "./Tile";

import Constants from "../constants/Constants";

import { TILE } from "../constants/Types";

const towerTarget = {

canDrop({ isMoveValid, isTheLatter }, monitor) {

const isOver = monitor.isOver();

const position = monitor.getItem().position;

const tileIsTheLatter = isTheLatter(position);

const target = parseInt(monitor.targetId.substr(1)) + 1;

return isOver && tileIsTheLatter ? isMoveValid(position, target) : false;

},

drop({ removeTile, addTile }, monitor) {

const position = monitor.getItem().position;

const target = parseInt(monitor.targetId.substr(1)) + 1;

removeTile(position);

addTile(position, target);

}

};

const collect = (connect, monitor) => ({

dropTarget: connect.dropTarget(),

canDrop: monitor.canDrop(),

isOver: monitor.isOver()

});

class Tower extends Component {

render() {

const background = this.props.isOver ? `#800` : `#764abc`;

const style = {

height: `calc(${Constants.TOWER_HEIGHT})`,

border: "4px solid white",

borderRadius: "20px 20px 0 0",

display: "grid",

alignContent: "flex-end",

background: background

};

return this.props.dropTarget(

<div style={style}>

{this.props.tiles && this.props.tiles.map(tile => <Tile key={tile.id} position={tile.id} />)}

</div>

);

}

}

export default DropTarget(TILE, towerTarget, collect)(Tower);

The drop target — DropTarget — class, is pretty similar to the drag source in which concerns the contract and signature.

The first function, canDrop, checks for the boolean value of whether the current operation of dropping is allowed or not.

Three conditions must be met here:

App.js).The drop function, in turn, will take care of removing the current tile from the tower it was placed at, and then add the same to the new tower.

The implementation of these functions will be made in the App.js file since we need these operations to be performed in the same place the state is.

The last file to be created under this folder is the HanoiTower.js:

import React, { Component, Fragment } from "react";

import Tower from "./Tower";

import Constants from "../constants/Constants";

class HanoiTower extends Component {

render() {

return (

<div style={style}>

{this.props.towers.map(curr => {

return (

<Fragment key={curr.id}>

<div />

<Tower

tiles={curr.tiles}

removeTile={tileId => this.props.removeTile(tileId)}

addTile={(tileId, towerId) =>

this.props.addTile(tileId, towerId)

}

isMoveValid={(tileId, towerId) =>

this.props.isMoveValid(tileId, towerId)

}

isTheLatter={tileId => this.props.isTheLatter(tileId)}

/>

</Fragment>

);

})}

</div>

);

}

}

const style = {

height: Constants.HANOI_HEIGHT,

display: "grid",

gridTemplateColumns: `

1fr

${Constants.TOWER_WIDTH}

2fr

${Constants.TOWER_WIDTH}

2fr

${Constants.TOWER_WIDTH}

1fr

`,

alignItems: "flex-end"

};

export default HanoiTower;

This class represents the root component of the game. After App.js, this component will aggregate the other inner component calls.

It places the grid styled nature of the game into the main div that constitutes it.

See that we’re iterating over the array of towers that comes from the main state (to be created).

Depending on how many towers we have there, this will be the number of piles that will be placed on the game screen.

The rest of the code is the style of the component itself.

The next two components are simply structural.

They will determine how the header and footer will appear in the game.

It’s just to make things more beautiful and organized. Here we have the code for Header.js (inside of structure folder):

import React, { Component } from "react";

class Header extends Component {

render() {

return (

<header

style={{

display: "flex",

justifyContent: "center",

alignItems: "flex-end"

}}

>

<h1

style={{

color: "#764abc",

fontSize: "3em",

fontWeight: "bold",

textShadow: "2px 2px 2px black"

}}

>

THE TOWER OF HANOI

</h1>

</header>

);

}

}

export default Header;

That’s just styled-component CSS configs. Nothing more.

Here’s the code for Footer.js:

import React, { Component } from "react";

class Footer extends Component {

render() {

const defaultStyle = {

color: "#764abc",

fontWeight: "bold"

};

return (

<footer

style={{

padding: "0.5em",

display: "flex",

justifyContent: "space-between",

alignItems: "center",

fontSize: "14px",

backgroundColor: "white"

}}

>

<p>

<span style={defaultStyle}>React-DND Example</span>

</p>

<p>

<span style={defaultStyle}>LogRocket</span>

</p>

</footer>

);

}

}

export default Footer;

Feel free to customize these components as much as you want.

Finally, let’s analyze the code of our App.js file.

In order to get our previous configured drag and drop components working, we need to provide a DnDProvider that encapsulates the rest of the DnD code.

import React, { Component } from "react";

import HanoiTower from "./hanoi/HanoiTower";

import Header from "./structure/Header";

import Footer from "./structure/Footer";

import Constants from "./constants/Constants";

import { DndProvider } from "react-dnd";

import HTML5Backend from "react-dnd-html5-backend";

class App extends Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = {

towers: [

{ id: 1, tiles: [] },

{ id: 2, tiles: [] },

{ id: 3, tiles: [] }

]

};

}

componentDidMount = () => {

const tiles = [];

for (let id = 1; id <= Constants.NUM_TILES; id++) {

tiles.push({ id: id });

}

this.setState({

towers: [

{ id: 1, tiles: tiles },

{ id: 2, tiles: [] },

{ id: 3, tiles: [] }

]

});

};

removeTile = tileId => {

var towerId = null;

this.setState(prevState => {

prevState.towers.forEach(tower => {

tower.tiles = tower.tiles.filter(tile => {

if (tile.id === tileId) {

towerId = tower.id;

return false;

} else {

return true;

}

});

});

return {

towers: prevState.towers

};

});

return towerId;

};

addTile = (tileId, towerId) => {

this.setState(prevState => ({

towers: prevState.towers.map(tower => {

tower.id === towerId && tower.tiles.unshift({ id: tileId });

return tower;

})

}));

};

isMoveValid = (tileId, towerId) => {

var tower = this.state.towers[towerId - 1];

if (tower.tiles.length === 0 || tileId < tower.tiles[0].id) {

return true;

} else if (tileId > tower.tiles[0].id || tileId === tower.tiles[0].id) {

return false;

}

};

isTheLatter = tileId => {

let tileIsTheLatter = false;

this.state.towers.forEach(tower => {

if (tower.tiles.length !== 0 && tower.tiles[0].id === tileId) {

tileIsTheLatter = true;

}

});

return tileIsTheLatter;

};

isVictory = () => {

const { towers } = this.state;

return (

towers[1].tiles.length === Constants.NUM_TILES ||

towers[2].tiles.length === Constants.NUM_TILES

);

};

render() {

return (

<div style={layoutStyle}>

<DndProvider backend={HTML5Backend}>

<Header />

<HanoiTower

towers={this.state.towers}

removeTile={this.removeTile}

addTile={this.addTile}

isMoveValid={this.isMoveValid}

isTheLatter={this.isTheLatter}

/>

{this.isVictory() && alert("Victory!")}

<Footer />

</DndProvider>

</div>

);

}

}

const layoutStyle = {

display: "grid",

gridTemplateRows: `

${Constants.HEADER_HEIGHT}

calc(${Constants.HANOI_HEIGHT})

${Constants.FOOTER_HEIGHT}

`

};

export default App;

Let’s break some things down.

The first important thing to note is the constructor.

It places our state and — since we’re not using Redux or any other state management lib — we’ll use the old React way to manipulate state values via props being passed down the components hierarchy.

Our towers array will consist of only three elements (remember to change the Constants class if you want to increase this value).

As soon as the component mounts, we need to initiate our array with the tiles stack within the first tower.

The componentDidMount function will take care of this.

Then, we have the auxiliary functions our inner components will use:

removeTileSets the new state by iterating over our towers array and searching for the corresponding tile id (passed as param).

addTileSets the new state by adding the passed to the tiles array of the respective tower selected, via unshift function (it adds the value to the beginning of the array).

isMoveValidChecks for basic rules of the game, such as whether a player is attempting to drop a smaller tile over a larger tile, etc.

isVictoryChecks for the conditions over the current state’s towers array to see whether the player has won the game or not.

The end of the code just uses the imported DnDProvider, passing the HTML5Backend as the backend for the provider.

Note also that every time this component re-renders, we check for the isVictory function to see if an alert message must be shown.

What’s missing is just the background image we’re using for the game (you can download it via GitHub project link, available at the end of the article); and the style.css code:

html,

body {

margin: 0;

padding: 0;

border: 0;

font-family: "Press Start 2P", sans-serif;

background-image: url(../img/bg.gif);

background-size: cover;

background-repeat: no-repeat;

}

Plus, don’t forget to import the style.css file in your index.js file:

import React from "react";

import ReactDOM from "react-dom";

import App from "./components/App";

import "./style/style.css";

import * as serviceWorker from './serviceWorker';

const mountNode = document.getElementById("root");

ReactDOM.render(<App />, mountNode);

// If you want your app to work offline and load faster, you can change

// unregister() to register() below. Note this comes with some pitfalls.

// Learn more about service workers: https://bit.ly/CRA-PWA

serviceWorker.unregister();

That’s it. You can access the full source code here at GitHub.

In this tutorial, we’ve configured and learned a bit more about how this powerful lib works.

Again, I can’t stress enough how important it is to get a closer look at the official documentation.

You can improve the game by adding some menus, a time counter to challenge the users, an option that allows users to input how many tiles they want to play with at the beginning of the game.

Regarding react-dnd, there are many more examples on their official website that you can use when looking for new functionalities in your application.

Install LogRocket via npm or script tag. LogRocket.init() must be called client-side, not

server-side

$ npm i --save logrocket

// Code:

import LogRocket from 'logrocket';

LogRocket.init('app/id');

// Add to your HTML:

<script src="https://cdn.lr-ingest.com/LogRocket.min.js"></script>

<script>window.LogRocket && window.LogRocket.init('app/id');</script>

Solve coordination problems in Islands architecture using event-driven patterns instead of localStorage polling.

Signal Forms in Angular 21 replace FormGroup pain and ControlValueAccessor complexity with a cleaner, reactive model built on signals.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the February 25th issue.

Explore how the Universal Commerce Protocol (UCP) allows AI agents to connect with merchants, handle checkout sessions, and securely process payments in real-world e-commerce flows.

Would you be interested in joining LogRocket's developer community?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now