Mountaineer is a framework for building web apps in Python and React easily. The idea of Mountaineer is to let the developer leverage previous knowledge of Python and TypeScript to use each language (and framework) for the task they are most suitable for.

The basic idea is to develop the frontend as a proper React application and the backend as several Python services: everything in a single project, types consistent up and down the stack, simplified data binding and function calling, and server rendering for better accessibility.

In this article, we will describe the setup of a Mountaineer project and show how to develop a simple application containing all the basic concepts. By the end, you’ll be able to seamlessly integration frontend and backend components in a single project.

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

Before starting, it is important to set up a proper environment. Mountaineer essentially transplants a React project, which is a Node application, into a Python environment. So, it can be quite picky about versions of each component in the environment.

In my setup, WSL is running quite an old version of Ubuntu (Ubuntu 20.04.6 LTS) under Windows, so I had to update the following packages:

These settings will change once Mountaineer becomes stable. It is also worth mentioning that the author was responsive and supportive when I had problems setting up the system.

Once your environment is set, you can create a boilerplate application by using the following command:

pipx run create-mountaineer-app

This is the facility available to create the (pretty intricate) directory structure with all the dependencies of the two, co-existing environments: the Python project and the Node project.

In the following figure, you can see the output of the command, which may vary depending on pre-existing requisites:

$ pipx run create-mountaineer-app ? Project name [my-project]: microblog ? Author [Rosario De Chiara <[email protected]>] ? Use poetry for dependency management? [Yes] Yes ? Create stub MVC files? [Yes] No ? Use Tailwind CSS? [Yes] No ? Add editor configuration? [vscode] vscode Creating project... Creating .gitignore Creating docker-compose.yml Creating README.md Creating pyproject.toml Creating .env Creating microblog/app.py Creating microblog/main.py Creating microblog/cli.py Creating microblog/config.py Creating microblog/__init__.py Creating microblog/views/package.json No content detected in microblog/views/tailwind.config.js, skipping... No content detected in microblog/views/postcss.config.js, skipping... No content detected in microblog/views/__init__.py, skipping... No content detected in microblog/views/app/main.css, skipping... No content detected in microblog/views/app/home/page.tsx, skipping... No content detected in microblog/views/app/detail/page.tsx, skipping... No content detected in microblog/controllers/home.py, skipping... No content detected in microblog/controllers/detail.py, skipping... Creating microblog/controllers/__init__.py No content detected in microblog/models/detail.py, skipping... Creating microblog/models/__init__.py Project created at /home/user/microblog Creating virtualenv microblog-IiOnN0qh-py3.11 in /home/user/.cache/pypoetry/virtualenvs Updating dependencies Resolving dependencies... (1.3s) Package operations: 29 installs, 0 updates, 0 removals [....INSTALLATION OF PYTHON PACKAGES....] Writing lock file Installing the current project: microblog (0.1.0) Poetry venv created: /home/user/.cache/pypoetry/virtualenvs/microblog-IiOnN0qh-py3.11 added 129 packages, and audited 130 packages in 9s 34 packages are looking for funding run `npm fund` for details found 0 vulnerabilities Environment created successfully Creating .vscode/settings.json Editor config created at /home/user/microblog $

If you look closely, you can spot two distinguishable phases of dependencies installation. Note how create-mountaineer-app is not only able to generate the scaffolding of the app but also to populate it with a sample MVC project.

For this article, we won’t use this function but we will implement a sample application by hand with this command:

$ poetry run runserver

You will be able to start the web server (see http://127.0.0.1:5006/) and begin developing the application with the useful hot reload once the source code is modified.

I must admit, the first run is not very exciting – there is no loaded page and the output is pretty dull:

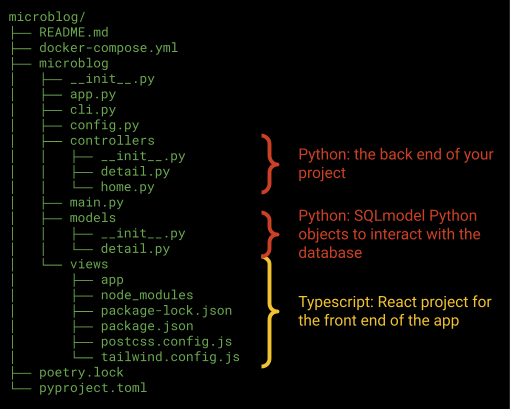

Before starting the development, let’s look at the directory structure that is created by the script we just ran. From the descriptions, you should be able to understand where to concentrate depending on what you intend to do:

Creating a page involves setting up a new controller to define the data that can be pushed and pulled to your frontend.

Let’s create a controller named home.py in the directory controller; as a controller, it will run on the backend and, as you probably expect, it is a Python script.

The general idea is to have an instance of the ControllerBase class and implement the method render that provides the raw data payload that will be sent to the frontend on the initial render and during any side effect update.

In most cases, you should return a RenderBase instance (see below) but if you have no data to display, you can also return None, like we do here. Additionally, we have to set the url parameter that contains the URL on which the controller is reachable, and the view_path that associates the view to this controller.

The render() function is a core building block of Mountaineer and all controllers need to have one: it defines all the data that your frontend will need to resolve its view:

from mountaineer import ControllerBase

class HomeController(ControllerBase):

url = "/"

view_path = "/app/home/page.tsx"

async def render( self ) -> None:

pass

The next step is to register the new controller in app.py:

from mountaineer.app import AppController

from mountaineer.js_compiler.postcss import PostCSSBundler

from mountaineer.render import LinkAttribute, Metadata

from intro_to_mountaineer.config import AppConfig

from intro_to_mountaineer.controllers.home import HomeController

controller = AppController(

config=AppConfig(), # type: ignore

)

controller.register(HomeController())

At this point, if you save your file, the server will automatically reload, registering the new controller but complaining about the missing page.tsx, which is the view we have associated with the new controller.

The view is, of course, a TypeScript/React file:

import React from "react";

import { useServer } from "./_server/useServer";

const Home = () => {

const serverState = useServer();

return (

<div>

<h1>Home</h1>

<p>Hello, world!</p>

</div>

);

};

export default Home;

You have to create the directory path /app/home/ under /view/ where our React project lives and place the file above, named page.tsx.

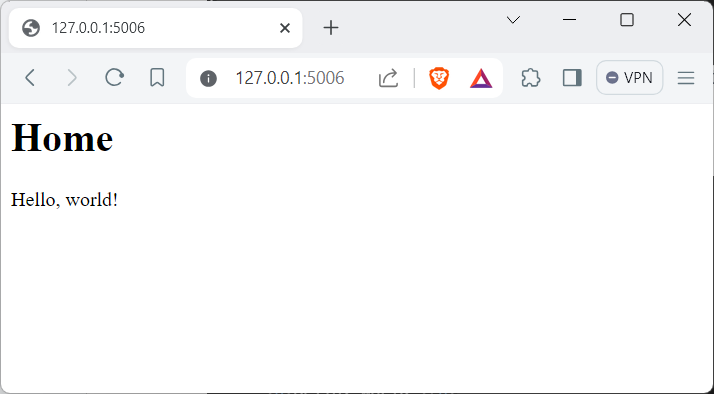

If you placed everything in the correct places, your browser will refresh and show the newly created page:

If you have a problem placing the right file in the directory, check this specific commit on the repo and see how the application looks.

One smart idea of Mountaineer is that it comes with the support of a PostgresSQL database to back your data. To facilitate its use, together with the files in your project, the create_mountaineer_app script also creates a docker-compose.yml YAML file to start the PostgresSQL server in your docker. You do not have to handle the process of building tables; Mountaineer will just inspect your code in the /model directory to understand what objects you need in the database.

The first step is to create a new Python script. In this example, it will be blogpost.py in the /model directory:

from mountaineer.database import SQLModel, Field

from uuid import UUID, uuid4

from datetime import datetime

class BlogPost(SQLModel, table=True):

id: UUID = Field(default_factory=uuid4, primary_key=True)

text: str

data: str = datetime.now()

To add this file to the project, you have to include it in the __init__.py Python file:

from .blogpost import BlogPost

At this point, we are ready to create the table in the database with the following commands. Of course, you must have a docker installation in your system on which to instantiate the container:

docker-compose up -d poetry run createdb

The createdb script will look into the /model directory and, for each object that has been included in the initialization file __init__.py, it will create a table with columns that match the names and types defined in the blogpost.py file (for this example).

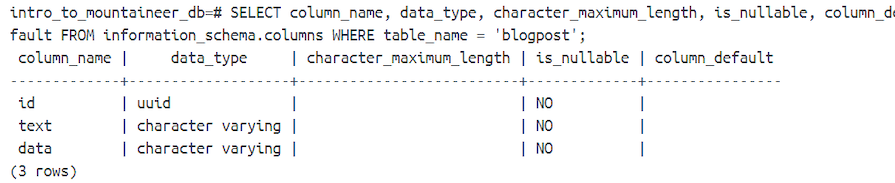

Out of curiosity, if you check your PostgresSQL database, you can see the structure of the blogpost table:

Now we have all the elements in place to complete the development of the application. First, let’s add the functionality for adding a new blog post. To do so, we have to add the input fields to the frontend (in the /views directory) and update the controller to properly add a row to the blogpost table (in the /controllers directory).

We first add a new method in the backend, which is the controller, in the file /controllers/home.py (the complete file is on the repo):

class HomeController(ControllerBase):

url = "/"

view_path = "/app/home/page.tsx"

async def render(self) -> None:

pass

@sideeffect

async def add_blogpost( self,

payload: str,

session: AsyncSession = Depends(DatabaseDependencies.get_db_session)

) -> None:

new_blogpost = BlogPost(text=payload)

session.add(new_blogpost)

await session.commit()

In the code above, we define the method add_blogpost that is marked by the @sideeffect decorator. This says to Mountaineer that this code will have an impact on the data and for this reason, when invoked, the server state must be reloaded.

The add_blogpost method will simply input the parameter payload, which will contain all the data passed through from the backend and the session that contains the pointer to the database. By using the payload, we create a new BlogPost object instance, using the payload string to initialize it. The new_blogpost object is added to the session, which is translated to an insert in the Blogpost table in the database .

The second modification is in the view. Below is a snippet from the page.tsx file in the /views/app/home (the complete file is on the repo):

const CreatePost = ({ serverState }: { serverState: ServerState }) => {

const [newBlogpost, setNewBlogpost] = useState("");

return (

<div>

<input type="text"

value={newBlogpost}

onChange={(e) => setNewBlogpost(e.target.value)} />

<button

onClick={

async () => {

await serverState.add_blogpost({

payload: newBlogpost.toString()

});

setNewBlogpost("");

}}>

Post</button>

</div>

);

};

Working on the frontend, we define a new React component that is just a simple form to handle the textbox and the onClick event when we submit it. As you can see in the code above, we just invoked the backend service add_blogpost defined in the controller.

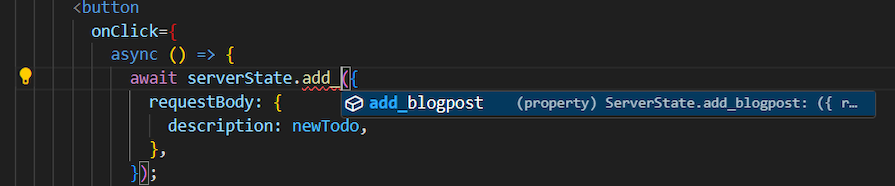

In the following image, you can see the real superpower of Mountaineer: the strong interconnection between the Python project and the React/TypeScript project:

In the React/TypeScript part of the codeblock above, we see the new function, add_blogpost() , added to the controller without any further configuration. Each time we modify the source code, Mountaineer incorporates the modifications by updating the type hints and function suggestions.

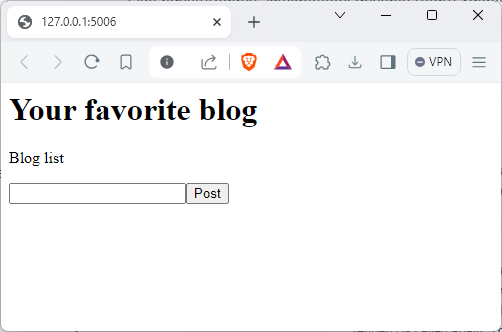

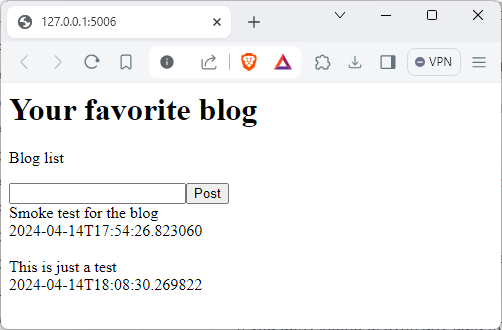

Once you complete all the modifications in the browser, you will be able to see the new UI:

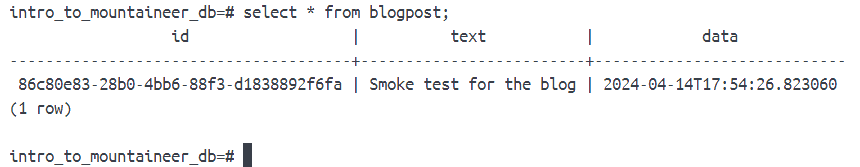

When you interact with the form by checking the database, you will be able to see that the whole process works:

Now we have a proper data flow from the frontend to the database through the backend. The last step is to implement the flow in the opposite direction, from the database to the frontend. This will involve changes in two places: the controller and the view.

The controller will have a new version of the render function:

async def render(

self,

request: Request,

session: AsyncSession = Depends(DatabaseDependencies.get_db_session)

) -> HomeRender:

posts = await session.execute(select(BlogPost))

return HomeRender(

posts=posts.scalars().all()

)

render is invoked during the initial render and on any sideeffect update. Its purpose is to provide the data from the database that will be sent to the frontend. The updates go into the server state by using the RenderBase instance to update it. In the example above, you can see how the array named posts is filled by executing a query on the specific object BlogPost.

On the view, we just have to manipulate the data from the serverState and assemble them in the interface: for this purpose, we wrote a new React component named ShowPosts:

const ShowPosts = ({ serverState }: { serverState: ServerState }) => {

return (

serverState.posts.map((post) => (

<div key={post.id}>

<div>{post.text}</div>

<div>{post.data}</div>

<br></br>

</div>

)))

}

We already know that in the serverState object, we will find an object named posts that is populated in the controller above. The updated files are on the repo and the final result is the following:

This project has some similarities with projects like ReactPy and PyReact. However, unlike those projects, it allows you to integrate both the frontend written in pure TypSscript/React and the backend in pure Python/Uvicorn into a single condebase, achieving strong coupling between the two layers by using Mountaineer.

Install LogRocket via npm or script tag. LogRocket.init() must be called client-side, not

server-side

$ npm i --save logrocket

// Code:

import LogRocket from 'logrocket';

LogRocket.init('app/id');

// Add to your HTML:

<script src="https://cdn.lr-ingest.com/LogRocket.min.js"></script>

<script>window.LogRocket && window.LogRocket.init('app/id');</script>

Compare the top AI development tools and models of March 2026. View updated rankings, feature breakdowns, and find the best fit for you.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the March 11th issue.

Buying AI tools isn’t enough. Engineering teams need AI literacy programs to unlock real productivity gains and avoid uneven adoption.

If your AI app or agent works perfectly in development but falls apart in production, you’re not alone. In a […]

Would you be interested in joining LogRocket's developer community?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now