The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

There are many tools available for analyzing your application’s performance. In this article, we will explore the Performance API, which is built into all modern browsers. Browser support for these APIs is very good, even going back as far as Internet Explorer 9.

During the lifetime of a page, the browser is busy collecting performance timing data in the background. It knows how long each step of the navigation process takes, and tracks the connection and download time of any external resources (static assets, API requests, etc.).

We’ll start by looking at the brains of this feature — the Performance interface — and look at how it calculates timestamps and durations. Next, we will look at some of the different entry types, and how we can create our own custom timings to analyze performance of any arbitrary code.

Jump ahead:

Performance interface and High Resolution TimePerformanceObserverPerformance interface and High Resolution TimeThe inbuilt performance monitoring APIs are all part of the Performance interface, exposed through the window.performance object. It captures many performance timings, including:

Using Date.now() to create timestamps is not ideal when trying to capture precise performance timings. A system’s clock may be slightly slower or faster at keeping track of the time. This is known as clock drift and it affects all computers to some degree.

This can result in inaccurate timings, especially when synchronization with a Network Time Protocol (NTP) server creates adjustments to the system time. This can skew comparisons with any previous timestamps.

For this reason, performance timings instead use a DOMHighResTimeStamp. The main differences with this type of timestamp are:

Starting from when the page first loads (more accurately, when the browser context is created), the window.performance object maintains a buffer of performance events. This is a live data structure and additional actions (such as asynchronous requests and custom user timings) will add new entries to this timeline.

The timeline is made up of objects implementing the PerformanceEntry interface. There are different types of performance entries, which are provided by subtypes from different APIs, but they are all collected together here in a single timeline.

The properties in an entry vary depending on the subtype, but they generally all have these in common:

name: An identifier for the entry. The value used for the name depends on the entry type; many entry types use a URL hereentryType: Specifies the type of performance entry. Each PerformanceEntry subtype specifies its own entryType; for example, a PerformanceNavigationTiming entry has an entryType of navigationstartTime: A high-res timestamp, relative to the time origin (usually 0, representing the moment when the context was created)duration: Another high-res timestamp that defines the duration of the eventThe Performance object has three methods for finding performance entries. Each method returns an array of PerformanceEntry objects:

getEntries: Returns all entries in the timelinegetEntriesByName: Returns all entries with a given name. A given entry type can also be given to filter the resultsgetEntriesByType: Returns all entries of a given typeYou can also listen for new entries to be added at runtime by creating a PerformanceObserver. This is given a callback function that handle new entries, and provides the criteria that entry types listen for. Any future entries that match the criteria will be passed to the callback.

The Resource Timing API provides PerformanceResourceTiming entries for each network request made by the browser. This includes asynchronous XMLHttpRequest or fetch requests, JavaScript and CSS files (along with referenced resources such as images), and the document itself.

The timings mostly relate to network events such as DNS lookup, establishing a connection, following redirects, and receiving the response. A full list can be seen in the PerformanceResourceTiming documentation.

The name property of these entries will refer to the URL of the resource that was downloaded. Entries also include an initiatorType property that denotes the type of request. Common initiator types are css, script, fetch, link, and other.

In addition to timing information, each entry also includes the response body size.

Below is a sample entry from the LogRocket website, loading the Avenir Heavy font file referenced from a link tag:

{

"name": "https://logrocket.com/static/Avenir-Heavy-65df024d7123b4108578ddbe666a9cba.ttf",

"entryType": "resource",

"startTime": 211.10000002384186,

"duration": 104.69999998807907,

"initiatorType": "link",

"nextHopProtocol": "h2",

"workerStart": 0,

"redirectStart": 0,

"redirectEnd": 0,

"fetchStart": 211.10000002384186,

"domainLookupStart": 211.10000002384186,

"domainLookupEnd": 211.10000002384186,

"connectStart": 211.10000002384186,

"connectEnd": 211.10000002384186,

"secureConnectionStart": 211.10000002384186,

"requestStart": 218.80000001192093,

"responseStart": 286.4000000357628,

"responseEnd": 315.80000001192093,

"transferSize": 59155,

"encodedBodySize": 58855,

"decodedBodySize": 134548,

"serverTiming": []

}

The very first entry in the performance buffer is a PerformanceNavigationTiming entry with an entryType of navigation. There is only one navigation entry, and its startTime will be 0, as it represents the start of the timeline. It contains timings for various events that occur as part of the navigating to, and loading of, the current page.

PerformanceNavigationTiming extends from PerformanceResourceTiming and inherits all of its network properties. It also includes timings related to loading DOM content, and firing the load event.

Here is a PerformanceNavigationTiming entry, again using the LogRocket website:

{

"name": "https://logrocket.com/",

"entryType": "navigation",

"startTime": 0,

"duration": 2886.300000011921,

"initiatorType": "navigation",

"nextHopProtocol": "h2",

"workerStart": 0,

"redirectStart": 0,

"redirectEnd": 0,

"fetchStart": 18.100000023841858,

"domainLookupStart": 20.600000023841858,

"domainLookupEnd": 58.80000001192093,

"connectStart": 58.80000001192093,

"connectEnd": 110.19999998807907,

"secureConnectionStart": 78.19999998807907,

"requestStart": 110.30000001192093,

"responseStart": 183.60000002384186,

"responseEnd": 209.19999998807907,

"transferSize": 93203,

"encodedBodySize": 92903,

"decodedBodySize": 468095,

"serverTiming": [],

"unloadEventStart": 0,

"unloadEventEnd": 0,

"domInteractive": 1371.9000000357628,

"domContentLoadedEventStart": 1384,

"domContentLoadedEventEnd": 1385,

"domComplete": 2879.900000035763,

"loadEventStart": 2880.199999988079,

"loadEventEnd": 2886.300000011921,

"type": "navigate",

"redirectCount": 0,

"activationStart": 0

}

Sometimes there may be operations other than resource and page loading that you want to measure. Maybe you want to see how well a piece of JavaScript performs, or measure the time between two events. The User Timing API allows us to create “marks” (points in time) and “measures” (measuring the time between two marks).

These functions create new entries in the performance timeline: PerformanceMark and PerformanceMeasure.

A performance mark is a named moment during the application runtime. It is used to capture a timestamp of an important event to be monitored. A mark is created by calling performance.mark with a name.

Suppose we want to calculate how long it takes to render a UI component. We can capture two marks: one just before the render begins, and another when it completes:

performance.mark('render-start');

// Perform the rendering logic

uiComponent.render();

performance.mark('render-end');

This will add two performance entries to the timeline, both of which have an entry type mark.

We can verify this by fetching all performance entries of type mark:

performance.getEntriesByType('mark');

The returned array of entries will include our render-start and render-end marks. Each mark specifies the starting time as a high-res timestamp.

To calculate the time elapsed between these tests, we can call performance.measure. This function takes three arguments:

performance.measure('render', 'render-start', 'render-end');

performance.measure calculates the time between the two named marks. The time measure will be captured in a new performance entry, with an entryType of measure, in the performance timeline.

The demo below shows marks and measures in action.

See the Pen

Performance Marks and Measures by Joe Attardi (@thinksInCode)

on CodePen.

PerformanceObserverSo far, we’ve seen how we can call getEntries and getEntriesByType to retrieve performance entries on demand. With the PerformanceObserver API, we can instead listen for new performance entries. We can set criteria to define the types of events we are interested in, and provide functions to call whenever matching entries are created.

This callback is passed to the PerformanceObserver constructor. When new entries are received, this function is called with a PerformanceObserverEntryList, which is an iterable data structure that contains all of the newly created entries. The observer itself is also passed as a second argument to the callback.

Once we have defined the callback and created a PerformanceObserver, it will not take effect until the observer’s observe method is called.

Below is an example of listening for all resource performance entries:

const observer = new PerformanceObserver(list => {

list.getEntries().forEach(entry => {

console.log(entry);

});

});

observer.observe({ type: 'resource' });

Here’s a demo of listening for resource entries and sending HTTP requests:

See the Pen

PerformanceObserver Demo by Joe Attardi (@thinksInCode)

on CodePen.

The Performance Timing APIs have very good browser support. According to data from caniuse.com, support for the core performance APIs goes back several years and versions:

Like any tool, there are advantages and disadvantages of using these APIs.

The strongest advantage of using the Performance Timing APIs to analyze your app’s performance is that they require no external libraries or services to capture their data. They are well integrated with the browser, especially for navigation and resource timing purposes. Detailed information is provided for these performance entries. The timings have very fine precision, and are not affected by clock drift.

The navigation timings start collecting the instant the context is created, so no data is missed as may happen using an external tool.

The downside of these tools are that they are usually not enough for a true solution on their own. Though they capture a lot of useful data about the browser session, there remain several gaps that you’ll likely need external libraries or services to fill.

We need a way to get the data off of the user’s computer and, likely, into an analytics tool in order for it to be of any use. This is not very difficult to solve from the client side; we just need to package up the data we have and send it off somewhere.

The Beacon API may be a good solution for this. It’s a lightweight “one-way” HTTP request that is particularly well-suited for sending analytics data. There are a few differences between a beacon and traditional asynchronous requests using XMLHttpRequest or fetch:

POST requests: A beacon can’t send a request with other methods such as PUT or PATCHNote that beacons are not supported on any version of Internet Explorer.

The data from the performance timeline is mostly raw timings. There is no metadata, such as the operating system or browser version. This data will have to be obtained separately and sufficiently anonymized in order to be sent along with the performance timings.

All of the performance entries in the buffer are specific to the current page. This is not an issue for single-page applications, but for multi-page apps, all previous performance data is lost when navigating away.

This can be solved fairly easily by sending a beacon when leaving the page, or using some intermediary persistent storage (web storage, IndexedDB, etc.).

The purpose of the Performance API is strictly to capture performance timings. It does not provide any other types of data. If you need to monitor user behavior or other metrics, you will need to reach for another tool.

The Performance APIs may be just one piece of an overall analytics solution, but they are an invaluable source of performance timing information that would otherwise be difficult to capture accurately. Even better is that we get it for free without needing to load any additional JavaScript or manually trigger any data collection!

We do have some extra work to do packaging the data and sending it to be aggregated, but it’s a very powerful tool built into today’s browsers. It also is well-supported on mobile device browsers.

Debugging code is always a tedious task. But the more you understand your errors, the easier it is to fix them.

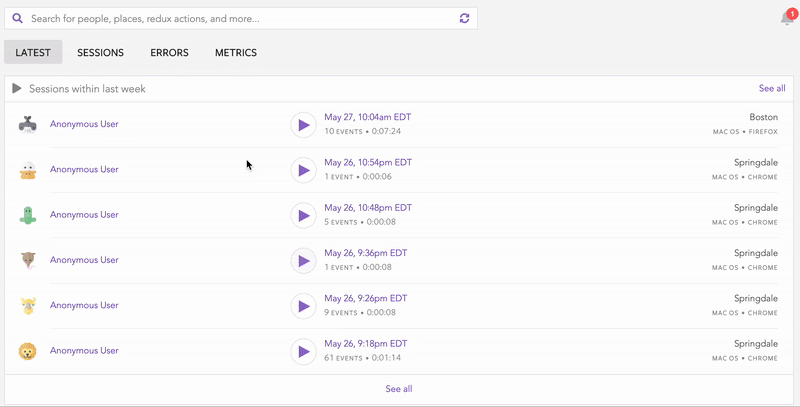

LogRocket allows you to understand these errors in new and unique ways. Our frontend monitoring solution tracks user engagement with your JavaScript frontends to give you the ability to see exactly what the user did that led to an error.

LogRocket records console logs, page load times, stack traces, slow network requests/responses with headers + bodies, browser metadata, and custom logs. Understanding the impact of your JavaScript code will never be easier!

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the March 11th issue.

Buying AI tools isn’t enough. Engineering teams need AI literacy programs to unlock real productivity gains and avoid uneven adoption.

If your AI app or agent works perfectly in development but falls apart in production, you’re not alone. In a […]

Compare ESLint and Oxlint, benchmark real speed gains, and learn when migrating to Oxlint makes sense for modern JavaScript teams.

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now