Product management requires investment; the investment of money, resources, time — the list is endless. It really comes down to those specific three, and sometimes those investments go awry. It’s just a part of the process.

Product managers must learn how to estimate the gravitas of the decisions that they make and how to cut their losses gracefully (with minimal damage) when they inevitably happen.

Thus, in this article, we’ll learn all about dealing with sunk costs in product management.

A sunk cost, less often referred to as a retrospective cost, is a financial investment that can’t be recovered if no return is made. There’s no refund, no back button, no possibility of a do-over.

Personally, I prefer the term “retrospective cost,” as “sunk cost” seems rather cynical. There are many different types of sunk costs and obviously, all of them are made with the best of intentions. If you’re wise and maybe a bit lucky, most of them will pan out successfully, propelling the product forward rather than sinking it along with the cost.

Different types of sunk costs include research and development, tools, facilities, marketing, salaries, and much more, all of which are necessary parts of running a business and managing a product.

Despite how negative the term “sunk cost” sounds, I’m not telling you to avoid them. It’s just that incurring a sunk cost is a permanent decision and those costs can rise even further if we fail to manage them effectively.

The term “sunk cost fallacy” refers to the invalid belief about a sunk cost. These sunk cost fallacies can cause us to act in ways that are bad for business, or not act at all.

What’s worse is that these fallacies are unconscious beliefs, so unless we know about them beforehand and make conscious efforts to separate fact from fiction, our brains are very likely to bamboozle us without us even realizing it.

If you’re wondering why our brains would ever betray us in such a way, consider this: bad outcomes result in stress and anxiety, so our brains tell us to avoid taking the actions that make us feel that way. Or, if we do take the actions and we somehow end up with bad outcomes, our brains are very likely to reframe how we interpret them — again, so that we don’t feel the horrible stress and anxiety.

Reframing could mean seeing the outcome as positive when in reality it’s negative (see the “this is fine” meme), or it could mean believing that we can turn a negative outcome into a positive one when in reality we can’t (in other words, the refusal to cut losses).

As a result, we might be reluctant to commit to sunk costs, which is a bad idea because they’re an important part of doing business. Or, we might be reluctant to accept that a sunk cost has had a negative outcome, which, in the worst-case scenario, could mean further losses.

Let’s take a look at some common sunk cost fallacies, why they’re bad, and what we can do as product managers to avoid them.

Loss aversion is a behavioral phenomenon where a loss is psychologically or emotionally more severe than its equivalent gain. As an example, where losing a $1,000 per year customer might feel devastating, gaining a $1,000 per year customer might only feel nice (or good, but probably not euphoric).

Loss aversion doesn’t necessarily affect performance or the outcome (in fact, it may improve it), however, once one observes negative outcome, the real danger rears its ugly head.

The real danger is, of course, reacting emotionally, which increases the likelihood of making bad decisions. Fear of loss aversion can also dissuade us from even risking a loss — why risk feeling bad when the alternative is only feeling content?

The trick is to remove temperamental emotions from the equation and establish the cold, hard facts of the situation instead. Therefore, we’re not risking feeling bad to feel content, we’re risking losing $1,000 to winning $1,000 (in theory). We mustn’t assess risks emotionally; instead, we should calculate them methodically.

The framing effect is a cognitive bias where people make decisions based on how the information is presented (positively or negatively). In fact, we can use the same example as above.

If we were presented with the opportunity to make $1,000, we might feel inclined to take it; however, if the situation were presented to us but included the risk of possibly losing $1,000, we might feel less so.

In actuality, the outcome is the same regardless of how the situation is framed. It’s simply a case of fully understanding the potential risks and rewards and, again, making decisions based on having all of the facts.

Optimism bias (or “over-optimism bias,” “optimistic bias,” or “over-optimistic probability bias” — it probably has thousands of names) is the tendency to overestimate the likeliness of positive outcomes and underestimate the likeliness of negative outcomes.

Studies also show that committing to a decision makes us even more confident in it, which is likely because we feel as if we’ve taken a step toward a positive outcome when in reality we’ve only taken a step toward an unknown outcome.

Now, there’s nothing inherently wrong with this. In fact, diving into the unknown is a crucial part of product design (rapid prototyping especially). However, this is usually part of a methodical process that helps product teams learn as much as possible while spending as little as possible (low risk/high reward).

Therefore, avoid investing excessive amounts of time, resources, and/or money when diving into the unknown (especially when they’re sunk costs that can’t be recovered if things don’t work out).

Product managers (or team members in general) that feel a personal responsibility for success are more likely to be frugal when it comes to investing money and resources, and while more investment doesn’t necessarily mean better results, it’s still a critical part of the product management process that can’t be shied away from.

This effect only worsens with the number of bad decisions made, however, bad decisions are actually pretty common. In fact, it’s often easier and cheaper to make bad decisions so that we can just learn from them and move forward (aka failing faster, alluding to the fact that failure is inevitable).

Cheap ways to fail faster include low-fidelity prototyping (including paper prototyping), unmoderated UX and user testing, fake product testing, and guerrilla testing. Product design is only risky and expensive when it’s not guided by research, aka data and feedback.

To summarize, it goes without saying that product managers have to make hard decisions, but that doesn’t mean that you have to make them alone. By using research and democratizing product decisions (i.e. sharing the responsibility), problems go from “you vs. the team” to “the team vs. the problems.”

In fact, many product design methodologies have democratic processes built in, for example, the design sprint methodology uses dot voting. With this approach and mentality, you’ll fail, then learn, then succeed together.

That being said, shifting from an introspective mindset to an outward-looking mindset (one that’s more focused on the product rather than the impact we’re having on it) is easier said than done. It’s a mindset that grows in tandem with maturity that often takes many years to cultivate.

It’s also worth being mindful of the fact that those that feel personally responsible are likely to invest excess time, partly to make up for investing less money and resources but mostly because they’re likely to adopt a perfectionist attitude (which kills productivity very quickly). Try to avoid this at all costs, as it leads to product teams shipping products/features/improvements far slower than they should be.

Nobody likes to waste, and obviously, it’s good to avoid waste when at all possible. However, committing to using what would otherwise be wasted is often more wasteful.

For example, if your team uses a tool that hinders productivity, using it anyway to save money is only going to waste time instead. This equates to wasting money in the long run anyway. Instead, it’s better to just write these types of sunk costs off, or as they say, “take the L.”

The desire to not appear wasteful in front of others is a huge driver of this behavior, but as mentioned before, introducing democratic processes into the product design workflow can help product teams make these types of difficult decisions. It’s essentially positive reinforcement for those times when everybody is secretly thinking the same thing.

Sunk costs are incredibly difficult to manage from a product management perspective, but debatably even harder to manage personally. Fear of making the wrong decisions or fear of making decisions at all can paralyze teams, stalling them to a point where that in itself becomes a difficult problem to overcome.

Sometimes it’s just better to let sunk costs…well, sink. Meanwhile, consider investing in smaller incremental product improvements (or an MVP if you haven’t launched the product yet). More importantly, use research and democratic collaboration (avoiding herd mentality) to make data-driven decisions that are more likely to pan out or be easy to recover from if they don’t.

The worst-case scenario for most sunk costs should ideally be a learning experience. In hindsight, they can actually turn out to be rather informative.

You only lose when you don’t learn.

Featured image source: IconScout

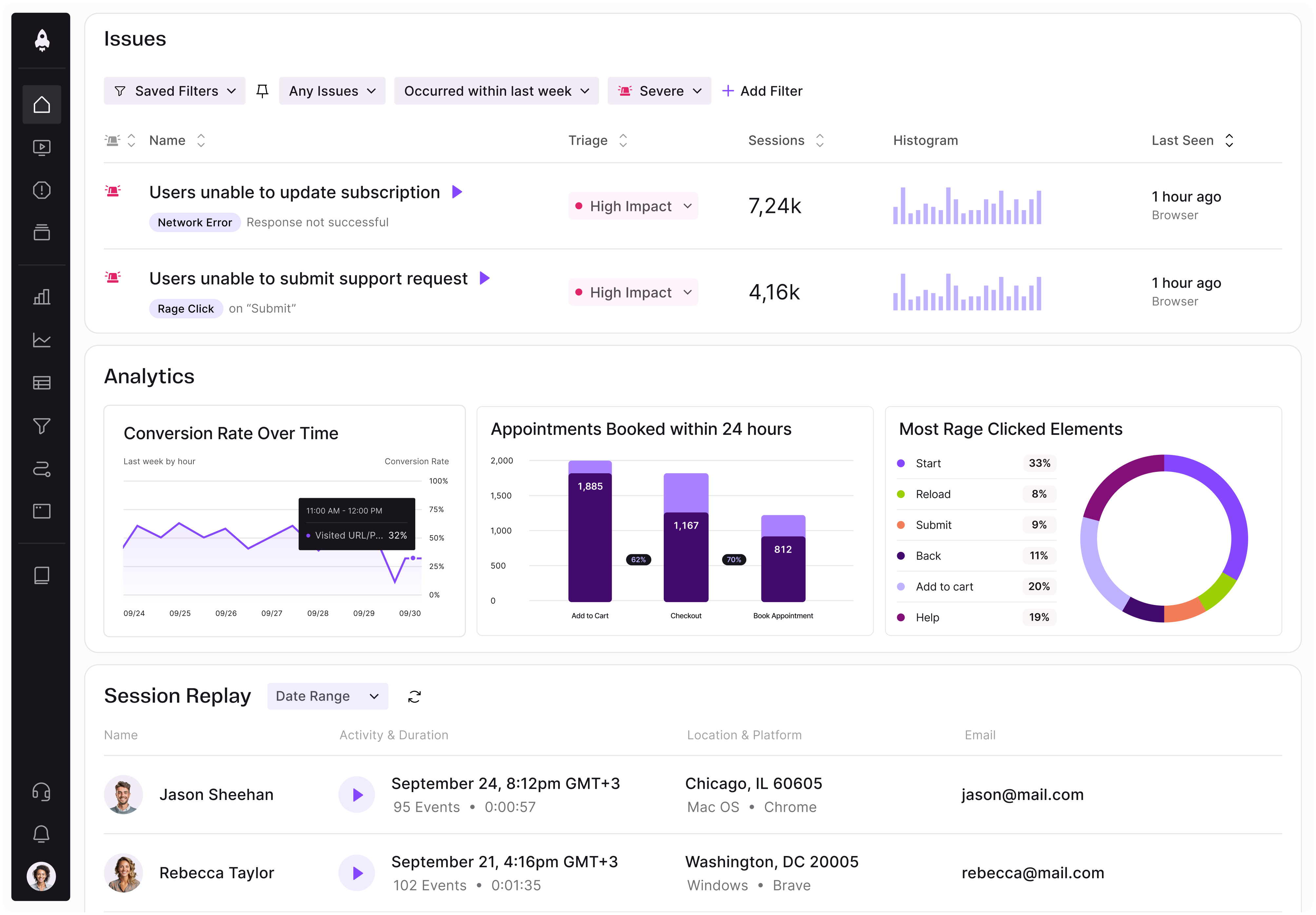

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

Rahul Chaudhari covers Amazon’s “customer backwards” approach and how he used it to unlock $500M of value via a homepage redesign.

A practical guide for PMs on using session replay safely. Learn what data to capture, how to mask PII, and balance UX insight with trust.

Maryam Ashoori, VP of Product and Engineering at IBM’s Watsonx platform, talks about the messy reality of enterprise AI deployment.

A product manager’s guide to deciding when automation is enough, when AI adds value, and how to make the tradeoffs intentionally.