Over the past five years, I’ve helped nine different startups transition from feature-factories to outcome-driven product management, with varying degrees of success. While outright failures (like a product team operating as an isolated island in a waterfall organization….) offer their own unique lessons, I found that I learned a lot more from a time when a seemingly successful transition inadvertently made things worse.

Introducing the autonomous, outcome-driven team, so hyper-focused on optimizing their tiny box that they completely miss the larger playing field. I call this the “tiny box problem.”

The following article walks you through a case study of a hypothetical company that suffers from the tiny box problem. By the end of the piece, you’ll be able to build strong, independent teams that keep their sights on what really matters.

Imagine ProjectY, a B2B SaaS offering an end-to-end project management tool for SMEs. After raising VC funds, ProjectY made the shift from founder-led sales and feature-driven development, to a product-led growth (PLG) model.

This comes with a tall order:

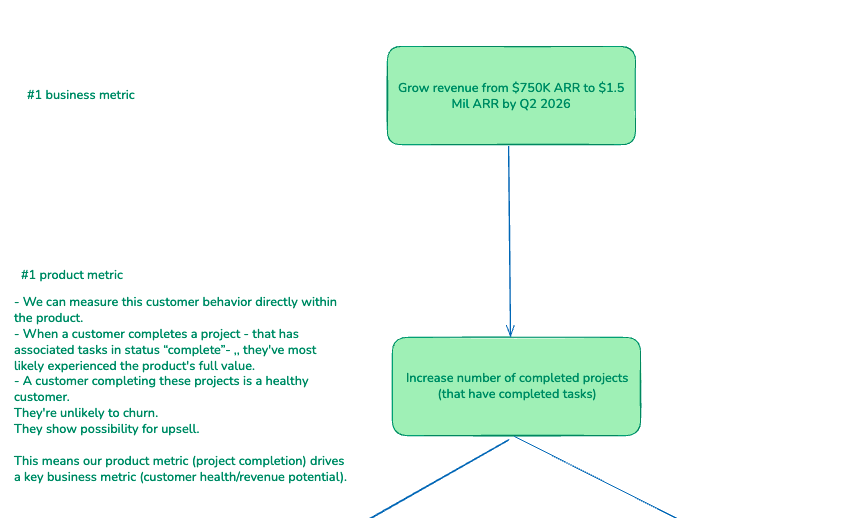

Luckily, ProjectY’s leadership understands that PMs can’t “drive outcomes” without knowing which outcome to drive. They move away from a laundry list of fuzzy, useless goals (like “be the best project management tool”) to something clean, meaningful, and useful:

Why this product outcome? The team believes that if a customer finishes a project that has completed tasks, it’s a strong indicator that this customer has experienced the core value of the product. Customers that complete tasks, and then projects, are considered healthy customers. Healthy customers are likely to upgrade from free to paid and unlikely to churn, thereby driving revenue:

You can complain as much as you want about feature- or stakeholder-driven product management, but it does make dividing labor nice and easy. Team A builds feature A, while Team B builds feature B. Each team can neatly estimate upfront the resources they’ll need since each has a pretty clear picture of what the solution will entail.

But alas. Gone are the days of PMs building features based on sales requests. ProjectY now has four PMs managing four dev teams, each tasked with delivering outcomes.

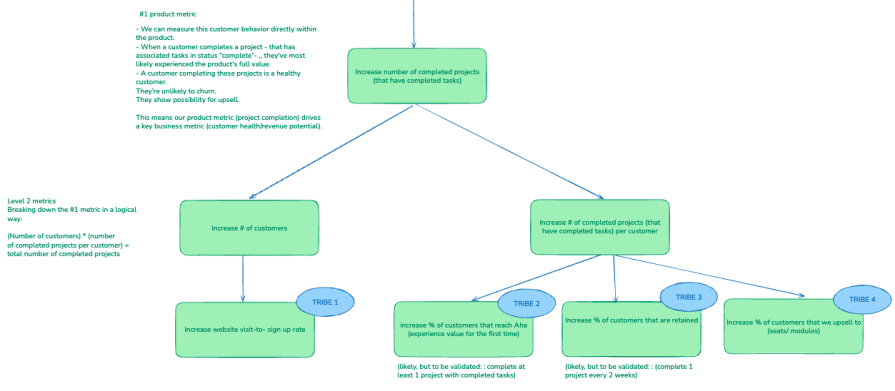

To avoid duplicate work, resource conflicts, and foster autonomy, ProjectY establishes four tribes, each focused on a specific outcome:

The number one product metric (“Increase completed projects with completed tasks”) is broken down into two different level two metrics: “Increase the number of customers” and “increase completed projects per customer.”

These are further decomposed into level three product metrics, each assigned to a specific tribe. The customer acquisition tribe focuses on website visit-to-signup rate, while customer aha/activation aims to increase the percentage of new users reaching the “aha!” moment.

If there are two things the leadership team at ProjectY hates, it’s teams:

To resolve this, a lot of effort is put into carving out autonomous teams — teams that can independently move the metrics they’re responsible for, from ideation to implementation.

Autonomy is a prerequisite for accountability: If you want teams to be responsible for driving outcomes, they need to be empowered to do so on their own. “We failed because we were blocked by XXX,” shouldn’t be an excuse!

Each team gets the personnel and resources to be able to move their metric independently.

For example, the customer acquisition tribe (“Increase website visit-to- sign up rate”) consists of a PMM, two frontend devs, one backend dev, and a CRO experienced PM.

So far so good.

ProjectY’s four tribes get to work:

Two teams focus on optimization (website and onboarding), while two others pursue two different paths toward “invoicing.”

The critical failure: none of the four teams see the bigger picture.

By targeting a far too broad ideal customer profile (SMEs), ProjectY has become an “anything to anyone” tool — a jack of all trades, master of none. The product lacks a strong competitive differentiator.

This is a company-wide, structural problem, impossible for any single team to solve autonomously. It requires cross-departmental collaboration, a longer time horizon, and most of all: courage.

But because it falls outside their specific “boxes,” no one raises it. Staring intensely at their individual level three metrics, teams miss the fundamental question:”What’s truly blocking us from acquiring new customers and delivering value?”

So, ProjectY burns through its runway, one small tweak and competitor-copy at a time.

Now, at this point, you’re probably asking yourself: How can you create autonomous, outcome-driven teams that still see the forest for the trees? There’s two key ways:

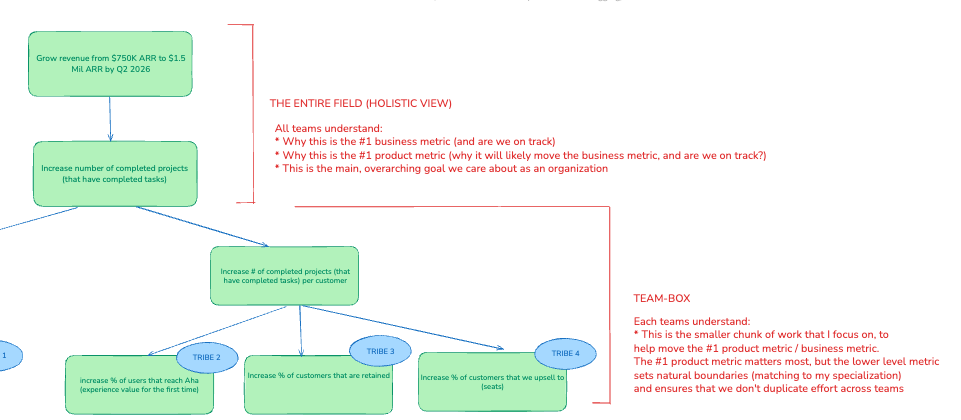

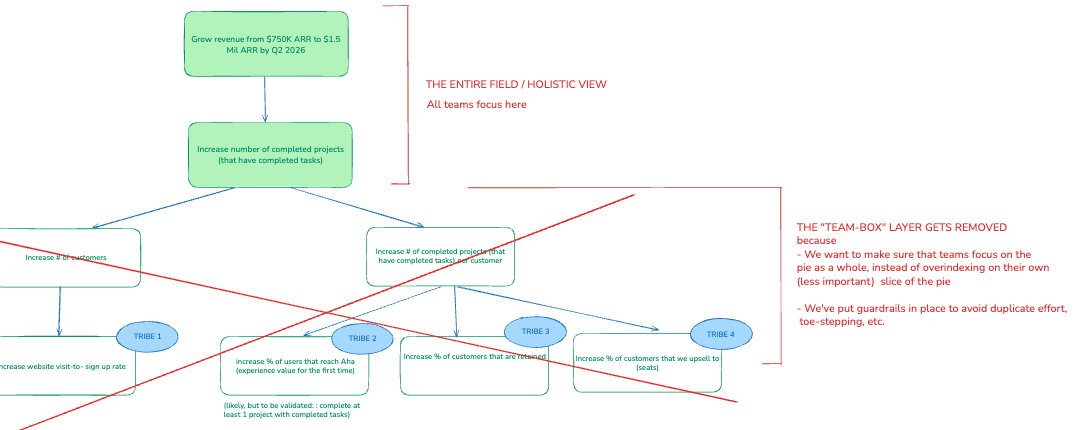

You need to refocus teams on the number one product and business metrics. The entire playing field, not just the tiny team-box. There are two primary approaches:

Teams still have their “boxes” (level three metrics like website visit-to-signup ratio), but they also see a holistic view of the business and understand that the overarching goal is to increase completed projects and, in turn, revenue. They understand the entire metrics tree and their role in driving the upstream metric(s).

Imagine the customer aha team realizing that continually tweaking the onboarding flow won’t solve ProjectY’s revenue goals if the product isn’t better than the competition. They’d “manage up” to leadership with constructive feedback and a resource request, outlining:

This approach also means the aha team should feel safe to suggest, for example, that overhauling the website would have the most impact on “projects completed,” rather than fearing stepping on the acquisition team’s toes.

Instead of each team playing in a dedicated box, what if every team was tasked with playing the entire field? This can be highly effective for smaller companies where frequent communication is natural. When everyone targets the same big goal, it fosters collaboration, reduces resource conflicts, and speeds up reactions to market changes.

This requires:

Popular opinion dictates that product teams should focus solely on leading product metrics, not lagging business metrics like revenue or retention.

The reasoning is sound: product teams tend to fail when tasked with vague, unactionable business metrics. A product metric — a measurable change in customer behavior indicating core value — is within their sphere of impact, it’s actionable, and a leading indicator for faster feedback loops. But what if the chosen product metric is wrong?

Product management embraces uncertainty. We must accept that our assumptions — even about the most critical business drivers — might be flawed. To catch these mistakes, everyone, especially product teams, should be encouraged to challenge assumptions beyond their immediate purview.

Product teams need to deeply understand the company’s overall strategy, revenue model, and why their number product metric is supposed to have an outsized impact. If moving the number product metric fails to move the number business metric, product teams should notice, hypothesize why, and raise their concerns.

Sometimes, zooming out to the business metric is more useful than staring at the product metric. In ProjectY’s case, staring at “increase completed projects” wouldn’t have led to the revelation “we should narrow our ICP.”

But moving from “we’re failing to grow revenue” to “we fail to acquire and retain customers” illuminated the root cause (“because we’re not special” → “because we’re not tight enough on who we’re building for”).

Because each team remains a specialist in its “box,” it’s up to them to:

This cultivates T-shaped people, bringing more diverse perspectives to each area, leading to better ideas and results.

Crucially, the leadership team should consistently provide access to the bigger picture: where are we going, and why? What’s worked, and what hasn’t?

Most importantly, leadership must want to be challenged, actively soliciting and valuing insights that might uncover systemic issues. This requires a culture where bringing up uncomfortable truths is rewarded, not penalized.

Autonomous, outcome-driven teams, without a wider vision, risk hyper-focusing on individual metrics, missing systemic issues and larger business opportunities. They optimize their “box” instead of seeing the entire playing field.

The good news is that you can escape this by expanding your scope and vision. To do this, keep the following three best practices in mind:

Featured image source: IconScout

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

Deepika Manglani, VP of Product at the LA Times, talks about how she’s bringing the 140-year-old institution into the future.

Burnout often starts with good intentions. How product managers can stop being the bottleneck and lead with focus.

Should PMs iterate or reinvent? Learn when small updates work, when bold change is needed, and how Slack and Adobe chose the right path.

AI accuracy problems are often chunking problems. Learn how chunk size and structure impact cost, retrieval quality, and UX.