Well, it’s official: Skype is shutting down in May. When I first saw this rumor a few days ago, I couldn’t believe my eyes. I immediately reached out to my former Skype colleagues to find that what had once seemed impossible was actually true.

For me, Skype was more than just a previous employer; it was a symbol of how my life evolved. I relied on it for years. It kick-started my career as a remote worker and later became a stepping stone when I joined the team as a senior product manager.

However, nostalgia only goes so far. The reality is that Skype has been deteriorating year after year. The writing was on the wall, and no one is truly surprised that Microsoft is shutting it down and migrating users to Teams:

So, what happened? Why is such an iconic product being discontinued? What could have been done differently? And most importantly, what lessons can product managers take away from this?

As the sun officially sets on Skype, let’s take a brief look at its history and then dive into the lessons we can all learn from its demise.

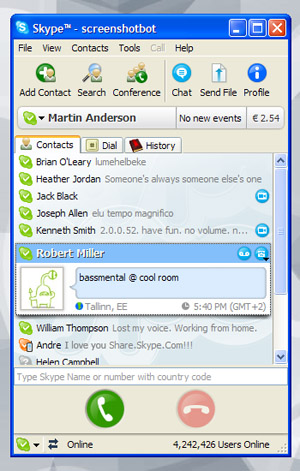

Skype started as a revolutionary tool that changed the way people communicated online. Launched in 2003 by Niklas Zennström and Janus Friis, it quickly became the go-to platform for free voice and video calls over the Internet:

At a time when international calling was expensive and unreliable, Skype disrupted the market, offering an easy, high-quality alternative. It grew rapidly, gaining millions of users worldwide. Though the $2.6B acquisition deal with eBay in 2005 didn’t quite work out in the end, Skype eventually landed with Microsoft in 2011 for $8.5 billion.

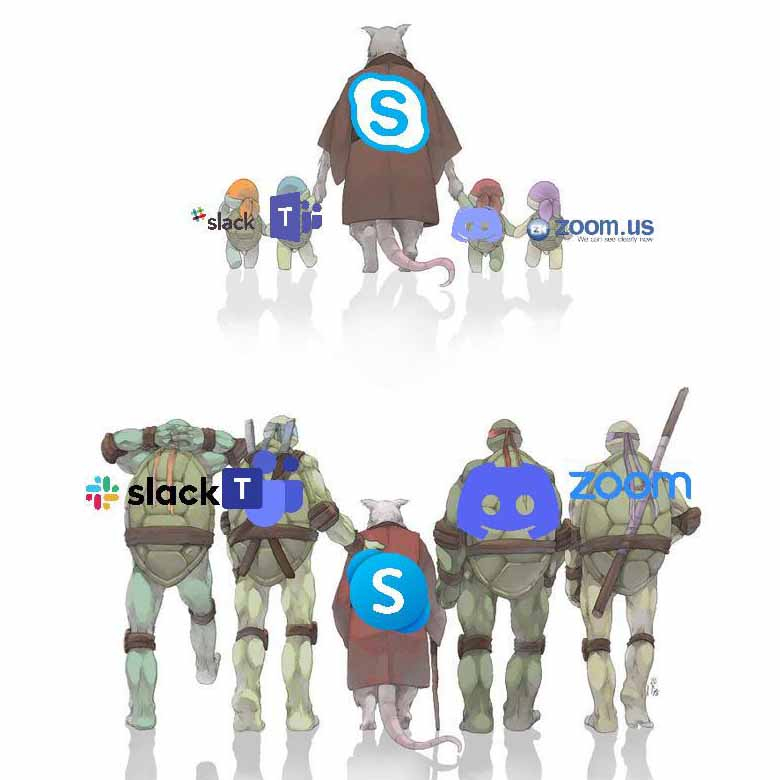

Microsoft had big ambitions for Skype, integrating it deeply into Windows and using it as a replacement for MSN Messenger. For a while, it remained dominant, but cracks began to show. The app became bloated, updates were inconsistent, and as competitors like Zoom and WhatsApp improved their services, Skype struggled to keep up.

Microsoft shifted focus to Teams, first positioning it as a business tool but eventually merging more consumer-friendly features. By the time Microsoft officially announced Skype’s shutdown this year, most people had already moved on. It was the end of an era for a product that once defined online communication.

So, what went wrong? When did Skype lose its way and could it have been prevented? Let me share my subjective view.

Long before joining the Skype team, I was a heavy user of the app. At the start of my career, I relied on it daily to meet with colleagues and clients. The only real downside was that it was hard to keep up with long threads and lacked structured, project-oriented group management.

However, at the time, there was no real alternative. If you needed a reliable, high-quality connection tool, Skype was the go-to option. Of course, there were competitors like BlueJeans, GoToMeeting, and even early Zoom, but Skype was the only platform that also allowed users to build a network of contacts they could easily reach.

Many say that things started going wrong when Microsoft took over, but that’s an oversimplification. The decline did not happen overnight. It took years, even decades before the final decision was made to shut Skype down. And again, I have to ask: was it necessary? Could it have been prevented?

As cliché as it sounds, the day Microsoft acquired Skype was the first step toward its eventual demise. The reason is simple:

Focus.

When Microsoft decided to compete with Slack by building Teams, they leveraged Skype’s backend to power it. That immediately raised an internal question. Why keep both products?

I would love to share the exact details of what I know from my time on Skype, but I also want to respect my former employer’s confidentiality. Instead, I will give you a general sense of what happened behind the scenes, and the lessons any product manager can take from Skype’s eventual fall.

To answer the Teams vs. Skype question, we had a straightforward corporate response. The two products served different audiences — Teams was for work (business meetings), while Skype was for personal use (keeping in touch with friends and family). While they offered similar functionalities, they were distinct enough to coexist.

But honestly, even though this answer was factually correct, it felt corporate and disingenuous.

The reality was that Skype was mostly used by small and medium businesses, while “friends and family” made up only a small fraction of our actual user base. And yet, we were strategically discouraged, if not outright forbidden, from developing business-oriented features. Instead, we were pushed to cater to the “friends and family” demographic, which, ironically, was not the group using Skype the most.

This put Skype in a confusing position. But why was it not fit for personal communication either? To understand that, we need to go back in the timeline again.

When Microsoft acquired Skype, technical excellence seemed to take a backseat. Instead of refining the product, the focus shifted to cramming in features and maximizing the number of users Microsoft could pull in.

Unfortunately, this resulted in many failed experiments and very few successes. Users grew frustrated, both with unnecessary features and declining call quality.

As the codebase aged, Skype became increasingly unstable and unreliable. Crashes became more frequent. I cannot pinpoint the exact moment when technical issues became severe, but I do know that at some point, Microsoft’s priorities shifted entirely. Teams became the company’s primary focus, while Skype was left behind and the team downsized significantly.

There was, however, one moment that could have turned things around: the COVID-19 pandemic.

I hesitate to call a global crisis an “opportunity,” but the reality is that Skype saw a massive surge in users when the pandemic began. Millions turned to video calling as a way to stay connected.

Unfortunately, technical issues, years of neglect, and an understaffed team meant that Skype could not capitalize on this momentum. Instead of experiencing a renaissance, it became a source of frustration, driving users to alternatives like Zoom.

Even the infamous “Zoombombing” incidents, where trolls crashed video calls, did not slow down Zoom’s rise. Meanwhile, Microsoft aggressively promoted Teams by offering it for free to large institutions suddenly in need of remote communication solutions. Skype, understaffed and underfunded, was left in the shadows:

Despite this, Microsoft still was not ready to abandon the brand entirely. Leadership was not willing to invest in making Skype great again, but they also were not ready to kill it off. This was the environment I stepped into when I joined Skype.

Here’s a fun fact: shortly before I was approached for the Skype role, I was recording a product management course. In a section about product life cycles, I joked that “no PM wants to join a dying product,” using Skype as an example. A few weeks later, I got my first interview for the role. (That joke was swiftly edited out of the course.)

But I digress.

During my time at Skype, I felt like I was witnessing another critical moment that could make or break the product. While we had little marketing budget and no real support from Microsoft leadership, our dedicated team came up with a simple but effective strategy:

Make Skype reliable.

We studied the numbers. Monthly active users were still in the high millions, and new users were joining every month. The problem? Even more were leaving. Our goal was to understand why and figure out how to keep them. Before I was laid off, we actually saw a minor uptick in growth. For the first time in years, things were looking hopeful.

But just as we started gaining traction, Microsoft’s approach to Skype shifted again. On one hand, leadership finally noticed us and wanted detailed updates on our progress. On the other hand, that attention meant realignment with Microsoft’s broader strategy, which was not about making Skype work better. It was about improving profits.

Of course, I cannot share internal financial details, but I can tell you this: Skype never stopped being profitable. The problem was that, on the grand scale of Microsoft, its profits were insignificant.

Thus, leadership reverted to the same old mistakes: adding new monetization features instead of fixing core issues. The strategy that had put Skype on the path to obsolescence was reinstated and accelerated.

By the time I left, Skype had an even smaller team, and the situation only got worse. Looking back, I feel like I left at a relatively high point (if you can call it that) before the final downfall became inevitable.

Now, let me play the “devil’s advocate” and look at this from Microsoft’s point of view.

While it’s easy to paint Microsoft as the villain, the reality is more complex. Microsoft is a shareholder-driven company, and even though Skype was in decent shape when acquired, it already had challenges adapting to the evolving internet landscape.

Slack was gaining traction, and new competitors were emerging. Microsoft had internal discussions about whether to acquire Slack or build its own competitor. They ultimately chose to develop Teams, using Skype’s backend as a foundation. From a business standpoint, this was a smart move.

Teams has since grown into a dominant platform, surpassing Slack in active users. It became the default choice for many companies, especially because it was bundled with Microsoft 365, making it a cost-effective option compared to Slack, which required a separate subscription.

Skype’s backend played a key role in Teams’ success, providing built-in video and voice call capabilities. Of course, the downside is that Teams inherited some of Skype’s technical baggage. It’s not exactly known for being the most stable or lightweight platform. But unlike Skype, Teams had Microsoft’s full backing, which meant resources, support, and continuous improvements.

What I’m saying is that Skype as a brand doesn’t really deliver any value to the company or users. It’s the solution it provided and now it doesn’t. It’s not a mistake to shut down Skype, but it’s a pity. A pity that could have been avoided.

For years, tech publications and industry experts questioned the need for both Skype and Teams. In the end, the decision to shut down Skype was a slow-boiling process, not a sudden shock.

It makes sense from a business and technical standpoint. But at the same time, it feels like watching an old cinema from your childhood being demolished to make way for new condos. Sure, the cinema was old, a bit rundown, and you had not been there in years. And yet, you still feel a pang of nostalgia, knowing it’s gone.

Farewell, Skype. Thank you for the memories, the opportunities, and for shaping my career. This did not have to be the way it ended, but given everything that happened, it’s only fair to move on.

Thank you for reading this more personal entry. I hope it gave you a deeper look into what happened behind the scenes and what we can learn from it. See you in my next post. Maybe it’ll be a little less personal, maybe not. But either way, until next time.

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

Rahul Chaudhari covers Amazon’s “customer backwards” approach and how he used it to unlock $500M of value via a homepage redesign.

A practical guide for PMs on using session replay safely. Learn what data to capture, how to mask PII, and balance UX insight with trust.

Maryam Ashoori, VP of Product and Engineering at IBM’s Watsonx platform, talks about the messy reality of enterprise AI deployment.

A product manager’s guide to deciding when automation is enough, when AI adds value, and how to make the tradeoffs intentionally.