Pushing out features into customers’ hands doesn’t guarantee value creation. We may think we know what customers want and how to collect business value from new features, yet we’re often wrong. It’s not about how fast you can ship new features; it’s about how fast you can learn what works and what doesn’t so you adapt course fast enough.

Product experiments, particularly pilot testing, can help accelerate this learning process.

In this blog article, I explore how product teams can benefit from pilot testing. I will begin with what pilot testing looks like, its benefits, the steps to conducting one, and the tools and techniques you can bring to use. I’ll also share a case study.

Pilot testing is a method for evaluating products or features with a controlled, selectively chosen group of users. The objective is to be as close as possible to those who will actually use the product so you uncover challenges and opportunities that could otherwise be missed in the development or prototype phases.

With pilot testing, product teams can quickly iterate the product until the control group receives the maximum benefit.

Pilot testing is often confused with beta testing, but there are key differences. Beta testing focuses on more users interacting, meaning the group is uncontrolled. Product teams can identify patterns and gather quantitative data. Pilot testing, on the other hand, helps product teams receive more qualitative feedback from a smaller, hand-picked group of users.

The two testing techniques — pilot testing and beta testing — complement each other, so it is normal to start with a pilot and then move to beta to increase confidence in market success.

You may ask why you’d want to invest time in pilot testing if you have already interviewed users, conducted prototype sessions, and collected considerable feedback before creating new features.

Well, users surprise us. Interviews and prototypes give, at best, moderate but not enough evidence to justify an upfront investment without involving customers until the feature is incorporated into the product.

Pilot testing will help product teams with the following:

Conducting a pilot test requires structure and alignment. Here’s what I like defining before starting the pilot:

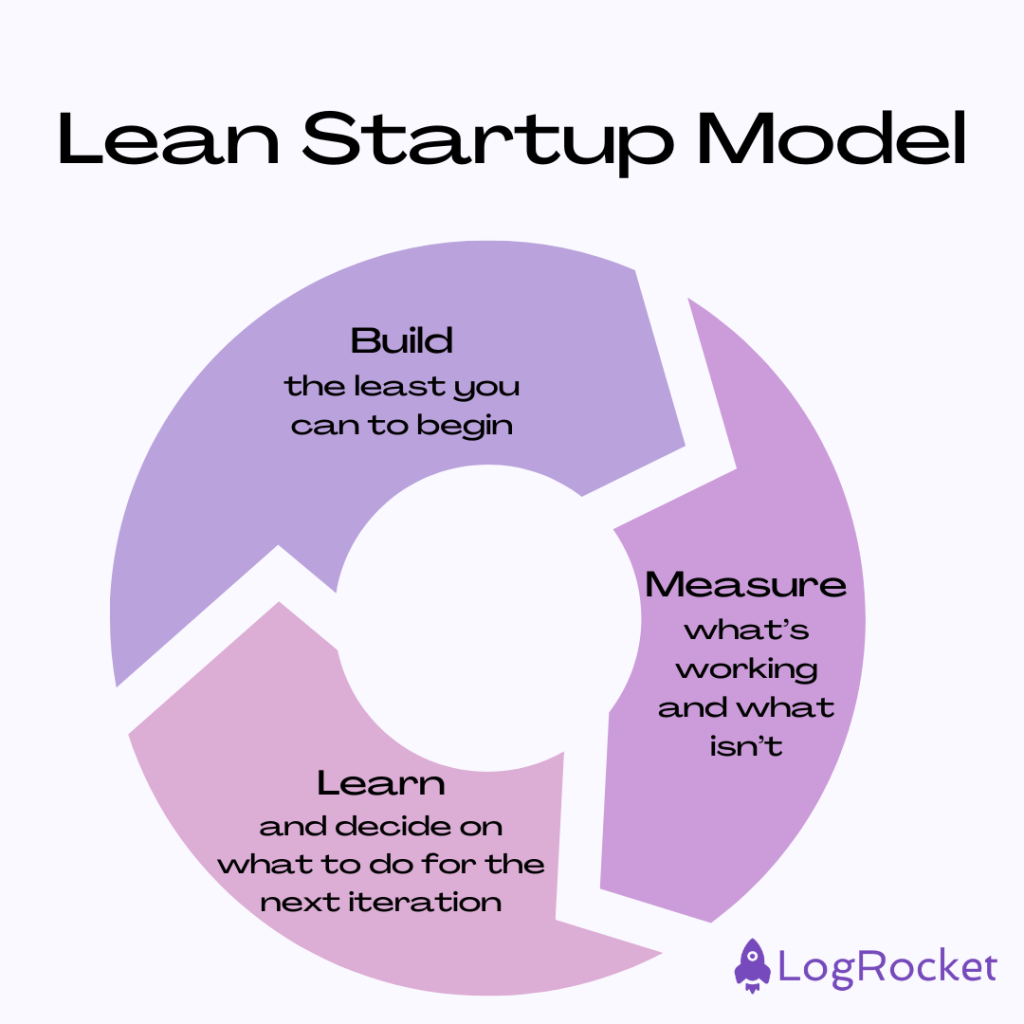

Once you’ve delineated the basics of pilot testing and established your framework, it’s time to move on to execution and iteration. A lean startup approach can benefit you:

Choosing the right tools for your pilot testing can be troublesome. But don’t bother too much about it — the goal is to learn from real users, not deploy the best tools. I recommend the following tools:

Remember — your objective is to learn as fast as possible. The longer it takes to learn, the riskier your product idea becomes.

You will face different types of resistance and challenges when you’re pilot testing. I’ll share the three most common challenges and how you can avoid them:

The pilot product version isn’t your first version. Treating it that way will mean taking too long to get it to users’ hands.

A common mistake is going into defining an MVP and then investing months into building it. With pilot testing, the goal is to build just enough for users to try and learn from the test. So, focus on the core aspects and leave the rest out.

If you choose to pilot test, remember that confronting your product against reality as fast as possible is mandatory. The advantage of a pilot is that it makes that possible with a small controlled group. You don’t need to fear repercussions. Embrace learning.

Some business stakeholders will inevitably be against pilot testing:

The above will increase the risks of failure. In such cases, I suggest taking 10% of the overall budget to run a pilot and learn whether investing further makes sense. When you limit the investment, you will be more pragmatic and use the pilot to boost learning, enabling you to make better-informed decisions.

Strive to move from opinions to evidence.

Many people confuse pilot testing with a validation of your product idea. That’s right up to a certain extent, but it’s a tricky approach.

We often fall prey to our biases when we try to prove ourselves right. We search for confirmation and usually find “positive signs” that our idea will fly. Yet, we fail to learn what we don’t know, missing valuable opportunities to make the product more relevant.

The goal isn’t to find reasons to build the way you want but to find reasons not to make it or to do it differently. Focus on falsifying your ideas instead of validating them. A learning attitude will help you uncover your blind spots.

Since early 2000, Google has developed a practice of letting employees invest a day a week into a side project, which gives them the flexibility to explore wild ideas.

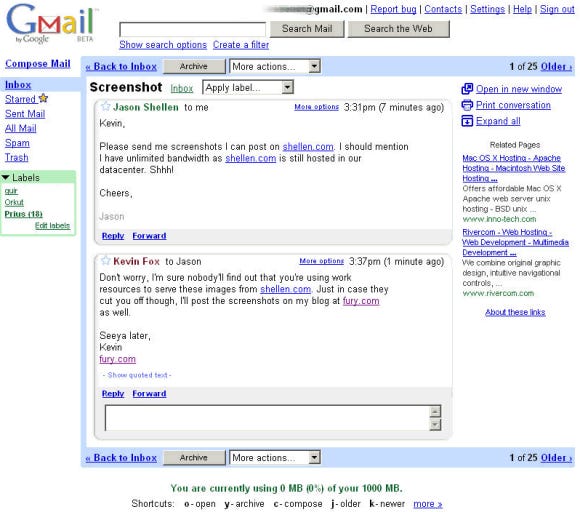

In 2001, Paul Buchheit, a software engineer, had the idea of creating a different way of handling emails. He was frustrated with limited storage, organization, and search options, so he came up with Gmail. This quickly moved from a side project to the most used email worldwide, though.

Pilot testing played a pivotal role in the success of Gmail.

As the product evolved, Paul Buchheit ran pilot testing with internal users in early 2003. The idea was to learn how the product solved the challenges Paul himself encountered. The pilot testing revealed aspects like:

With the feedback, the team improved the project, adding 1 GB of storage, something which was rather unimaginable in 2003. After that, Googlers gained trust in the product, and it was time to finalize the pilot as it achieved its objectives.

After the successful pilot, though, Google didn’t release Gmail to everyone. It first went into a beta release, where users could get in only with invitations. The objective was to slowly scale and learn how the product solved users’ challenges at scale.

Gmail was, then, officially launched in 2004 after successfully completing beta testing. Today, it’s the most used email worldwide. The initial pilot was fundamental to its success because it reviewed core flaws before reaching a mass audience. When the product arrived in users’ hands, it was already a better, more polished, and consistent version.

When you run pilot testing, most of your ideas will not go beyond it because you will discover that investing in them isn’t worth it. It’s normal to drop ideas after running a pilot.

And remember that beta testing isn’t the same as pilot testing. The first aims to address an uncontrolled group in a higher volume, collecting relevant quantitative data. The second targets a small controlled group, enabling you to gather qualitative data.

Pilot testing isn’t the first version of your product but a fast way of learning from real users in a controlled group. It aims to yield learning, not to prove yourself right. So, with pilot testing, you should strive to uncover your blind spots instead of letting false positives illude you.

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

Great product managers spot change early. Discover how to pivot your product strategy before it’s too late.

Thach Nguyen, Senior Director of Product Management — STEPS at Stewart Title, emphasizes candid moments and human error in the age of AI.

Guard your focus, not just your time. Learn tactics to protect attention, cut noise, and do deep work that actually moves the roadmap.

Rumana Hafesjee talks about the evolving role of the product executive in today’s “great hesitation,” explores reinventing yourself as a leader, the benefits of fractional leadership, and more.