When it comes to React applications, state is an integral part of what makes the application dynamic and interactive. Without state, applications would be static and unresponsive to user input.

State management is the process of handling the state of an application optimally. It is a crucial part of the development process. In this article, we will take a look at the different state management options available for React developers in 2023, and how to choose the right one for your project.

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

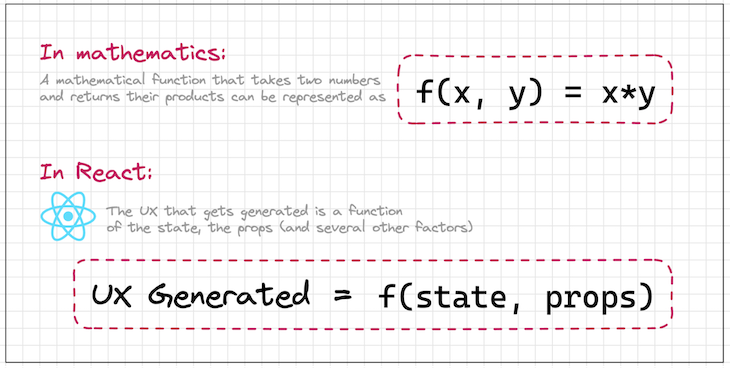

The UI that is generated in a React app is a function of the state. To invoke reactivity in an app, all we need to do is modify the state, and the React library will take care of the rest. The graphic below sums up the relationship between the application UX, state, and props in React:

React has a variety of built-in features for state management, including the useState and useReducer Hooks, as well as the Context API. Before exploring third-party libraries for state management, let’s take a look at these built-in features.

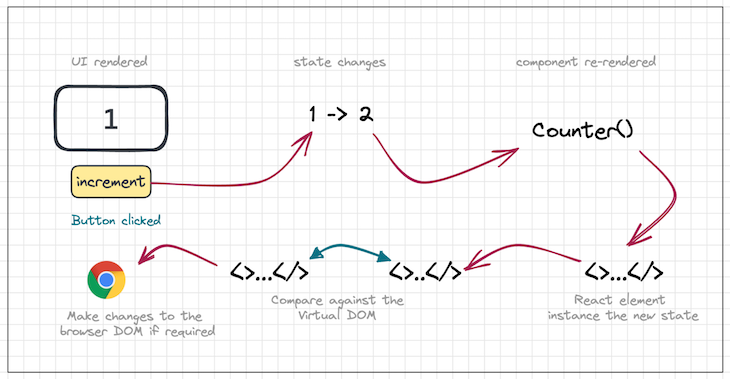

useState and useReducer HooksBoth the useState and useReducer Hooks have a different approach for how the state is updated. As mentioned above, both of these interfaces help us modify state. Beyond that, React takes care of all the heavy lifting required to faithfully represent that state on the browser DOM. The graphic below sums it up well:

useState HookThe useState Hook is the most basic API provided by React to interact with state. To better understand how this hook works, let’s look at a counter app example. First, let’s create the state:

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

The above piece of code creates a state variable called count and a function called setCount that can be used to update the state. The initial value of the state is set to 0. Now, we’ll update the state by incrementing the value of count by 1:

setCount(count + 1);

Finally, we’ll use the state:

<p>You clicked {count} times</p>

In this example, we used the state by displaying the value of count in the UI. Learn more about the useState Hook in this guide.

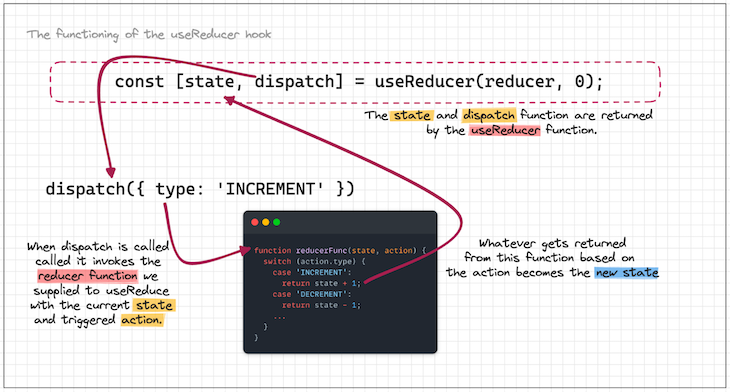

useReducer HookThe useReducer Hook allows us to manage state by dispatching actions and then responding to them in the reducer function. Again, we’ll use a counter app example to understand how this hook works:

const [state, dispatch] = useReducer(reducerFunc, 0);

We call the useReducer Hook with the reducer function and the initial state as arguments. It returns the current state and a dispatch function. Whenever we need to update the state, we can call the dispatch function with an action object:

dispatch({ type: 'INCREMENT' })

React then calls the reducer function with the action object. Here’s what a common reducer function looks like:

function reducerFunc(state, action) {

switch (action.type) {

case 'INCREMENT':

return state + 1;

case 'DECREMENT':

return state - 1;

case 'RESET':

return 0;

case 'SET':

return action.val;

}

}

At the end of this transaction, whatever the reducer function returns becomes the new state and is accessible through the state variable. Here’s a sketch that explains the flow of data in the useReducer Hook:

Read more about the useReducer Hook here.

useContext HookNext, let’s look at how the useContext Hook comes into the picture for state management. The general idea is to store a piece of data that components can use, but the pattern and the use cases are different.

While useState and useReducer are used to manage state that is scoped to a component, useContext is used to manage state that is shared across components. Its main purpose is to avoid prop drilling when a piece of state is supposed to be accessed by a child component several levels down the component tree. One of the primary use cases of context is to manage the theme of the application. So, let’s look at the code for the same.

Inside a component near the top of the component tree, we’ll create the context:

export const themeContext = createContext('light');

Notice how the newly created context object is exported from here. To use that context, we’ll import it in a component down the tree:

import { useContext } from 'react';

import { ThemeContext } from './App.js';

export default function Button({ children }) {

const theme = useContext(ThemeContext);

// ...

}

But, for the above code to work, we need to first wrap the component tree above this consumer component with the context Provider:

<ThemeContext.Provider value={theme}>

{children}

</ThemeContext.Provider>

With that in place, the consumer component will receive the value supplied by the Provider. Whenever the value supplied to the Provider is updated, the child below will be able to access that latest updated value. For more information about how the Context API can be used with the useContext Hook to manage state, check out this article.

While the above solution for state management makes sense when the scope of the state is just a single component (in the case of useState and useReducer), or when the state is supposed to be accessed in a downstream component (in the case of useContext), these restrictions make it difficult to use these solutions in larger applications where the order of creation and consumption of state is not defined. This is where third-party libraries come in.

Redux is one of the oldest and most popular libraries for state management in React. It has a large ecosystem of libraries and tools that make it easy to use in modern applications. The paradigm is similar to what we saw in the useReducer Hook, with the added advantage that the state is now global and can be accessed by any component in the application.

We’ll look into the react-redux library because that is the official binding for React. We’ll also need the redux-toolkit library, which will help us accomplish common Redux patterns while minimizing boilerplate code.

Similar to how the useContext Hook creates a context, which is a central place where the state is saved, the Redux library has a parallel concept called the store, which is the central state that is shared across components and acts as the source of truth. Let’s create the store:

import { configureStore } from '@reduxjs/toolkit'

import todosReducer from './features/todos/todosSlice'

import userReducer from './features/user/userSlice'

export default configureStore({

reducer: {

todo: todosReducer,

user: userReducer

},

})

The configureStore function from redux-toolkit does something similar to Redux’s store. It creates a single store by combining several reducer-like functions that your entire application can have.

Notice the todosReducer and the userReducer, which are being imported from separate slices. A slice is nothing but an abstraction, provided by redux-toolkit, that helps us specify a name, an initial state, and a reducer function for a particular piece (or slice) of the entire app state.

Now that the central store is created, it needs to be accessible throughout the application. The way to accomplish that is via a Provider:

import { Provider } from 'react-redux'

import store from './store'

root.render(

<Provider store={store}>

<App />

</Provider>

)

We import the previously created state and the Provider component from react-redux and wrap the entire application with it. With that set up, we are now ready to access the state inside our function components using the hooks that react-redux provides:

import { useSelector, useDispatch } from 'react-redux'

import { markDone } from './todosSlice'

export function Counter() {

const userName = useSelector((state) => state.user.name);

const dispatch = useDispatch();

...

dispatch(markDone(id));

The useSelector Hook lets us get ahold of a particular slice of state from the store. It also gets the latest value by re-rendering the component when that slice of state is updated. The useDispatch() Hook gives us access to the dispatch function, which is used to dispatch actions to the store exactly the same as we did in the useReducer Hook.With that, we have a React app that uses Redux for state management. It can be scaled up by adding more slices whenever the app adds more features.

MobX is another alternative for state management in React. It relies on the concept of observables. State is segregated into pure values and computed values. The core belief of MobX is that “Anything that can be derived from the application state, should be. Automatically.”

Let’s look at an example to better understand this. The state of the application is defined in the form of a JavaScript class. Here is an example of how a Todo item can be represented in state:

import { makeObservable, observable, action } from "mobx"

class Todo {

id = Math.random()

label = ""

done = false

constructor(label) {

makeObservable(this, {

label: observable,

done: observable,

toggle: action,

summary: computed

})

this.label = label

}

toggle() {

this.done = !this.done

}

get summary() {

console.log("summarizing...")

return `${this.label} ${this.done ? "is" : "is not"} done.`

}

}

We can see that the class has three properties: id, label, and done. Notice how the constructor calls the makeObservable function imported from Mobx, which defines the properties as observables. The summary property is being defined as computed, which means it will be re-calculated every time an observable dependency changes. The toggle function is defined as action.

With that general understanding of how Mobx works, let’s try to use it in a React application. We will use the mobx-react-lite package, which provides lightweight bindings for React to interact with Mobx.

If we don’t want to make the class defining the state more complex, we can use a utility like makeAutoObservable:

constructor() {

makeAutoObservable(this)

}

With this utility, we need not individually specify the types for individual properties (e.g. observable, action, computed) like we did in the previous example. When we call makeAutoObservable in the constructor, all own properties inside the class are marked as observable, all getters are marked as computed, and all setters as actions.

Once that is set, we can move on to integrating this with our React component. This is where the observer utility from Mobx comes into play. We just need to wrap our React component with the observer HOC and everything else is taken care of for us:

const Task = observer(({ todo }) => (

<>

<h1>Task: {todo.summary}</h1>

<button onClick={() => todo.toggle()}>Toggle</button>

</>

))

In the example above, we can see that the Task component is being passed a todo prop, which is an instance of the Mobx store we created above. As we are accessing the summary property of the todo object, Mobx automatically takes care of re-rendering the component whenever the value of summary changes. We don’t need to do anything extra. Isn’t that great?

This is the core concept around reactivity in Mobx. Based on the property that we access, Mobx will re-render our component whenever only the accessed property changes. For example, we are currently accessing the summary observable, which means this component will re-render only when that particular observable from the class changes. If there was another observable in the class that never gets accessed in this component, it would not have any impact on the re-rendering of the component. This mimics the behavior of subscribing to changes in the state, similar to Redux, and without the need to explicitly do so.

Recoil is a newer library for state management in React that takes the atomic approach to state management. Atomic state management is a paradigm where the state of an application, instead of being stored in a single, large object, is broken down into smaller independent units of state called atoms.

An atom represents a piece of state that can be read to or written from any component. Any component that reads the value of an atom is automatically subscribed to that atom and will be re-rendered whenever the value of the atom changes.

For the application to be able to read and write to Recoil state, we need to wrap our parent component in RecoilRoot:

import { RecoilRoot } from 'recoil';

function App() {

return (

<RecoilRoot>

<SayHi />

</RecoilRoot>

);

}

With that in place, we can create and consume state. We can use the atom utility provided by Recoil to create atoms:

const firstNameState = atom({

key: 'firstNameState',

default: 'Bob',

});

We can also create a derived state that depends on the two states above and returns a transformed output:

const introductionState = selector({

key: 'introductionState',

get: ({get}) => {

const name = get(firstNameState);

return `My name is ${name}!`;

},

});

In the example above, we created a greetingState derived state using the selector utility provided by Recoil. Now, to access these in the component and make modifications, we can use the useRecoilState Hook:

function SayHi() {

// firstNameState & introductionState is the atom we created above

const [firstname, setFirstName] = useRecoilState(firstNameState);

const introduction = useRecoilValue(introductionState);

const onChange = (event) => {

setFirstName(event.target.value);

};

return (

<div>

<input type="text" value={text} onChange={onChange} />

<br />

<h1>Hello from {firstname}!</h1>

<h2>{introduction}</h2>

</div>

);

}

Notice that we also used the useRecoilValue tool to access the value of the derived state. The core philosophy is that when any name is typed in the input box, setFirstName gets called, which updates firstName. This also triggers an update on the derived state introductionState, and we can see the latest results on the page. Jotai does something similar while bringing a few special capabilities to the table.

Similar to Recoil, Jotai is a state management library that also takes an atomic approach to state management but in a slightly different way. This library also provides an atom utility to create atoms:

const firstNameAtom = atom('Bob');

const personAtom = atom({

firstName: 'Bob',

lastName: 'Ross',

age: 35

});

There is also a provision to create a derived state:

const greetingAtom = atom((get) => {

const firstName = get(firstNameAtom);

return `My name is ${firstName}!`;

})

Once created, this atom can be consumed and updated inside a React component similar to the useState Hook:

const [firstName, setFirstName] = useAtom(firstNameAtom);

There are a few functionalities that make Jotai unique when compared to Recoil. For example, the atomWithStorage utility is exported from jotai/utils and persists the state onto LocalStorage so we don’t lose the value even after a refresh! This is useful when we need to store something like a user’s dark mode preference.

Jotai also provides separate integrations with libraries like Immer, Query, XState, etc. For instance, atomWithImmer exported from jota-immer lets us create an atom with an immer-based write function. These utilities are what make Jotai a unique choice as a state management library.

Signia is an alternate library for state management in React. Instead of using observables like Mobx, or atoms like Recoil and Jotai, it uses the concept of signals. A signal is a pure, reactive value that can be observed for changes.

Even though the underlying entity is a signal, the Signia library allows us to create atoms that are based on signals:

import { atom } from 'signia'

const fruit = atom('fruit', 'Apple');

Updating the value of a signal is done by calling the set method on the atom:

fruit.set('Banana');

console.log(fruit.value); // Banana

Signia also has the concept of computed state, similar to Recoil and Jotai. It is created by using the atom.value property of any atom inside the compute function:

const fruits = atom('fruits', 'Apples')

const numberOf = atom('numberOf', 10)

const display = computed('display', () => {

return `${numberOf.value} ${fruits.value}`

})

Read more about state management with Signia in this article.

Although state machines are not explicitly used in React, they can be powerful tools for managing state in React applications. A state machine is an entity that has a current state and can transition to other states based on certain events. This is similar to the concept of Redux, where we have a state and can dispatch actions on that state. But state machines have added advantages, like the ability to have parallel states, hierarchical states, and more.

Working with states and managing transitions between them natively is a complicated affair. XState is a library that provides primitives that help us work with state machines. It also provides React bindings so that the state machine can be used in a React component.

Here’s what a general state machine defined with XState looks like:

import { createMachine } from 'xstate';

const todoMachine = createMachine({

id: 'todo',

initial: 'pending',

states: {

pending: { on: { TOGGLE: 'done' } },

done: { on: { TOGGLE: 'pending' } }

}

});

Notice how this is a neat way to define all the states, the initial state, and also the actions that lead to particular states. This state machine can then be used inside a React component using the hooks exposed by @xstate/react:

import { useMachine } from '@xstate/react';

import { todoMachine } from '../todoMachine';

function Toggle() {

const [current, send] = useMachine(todoMachine);

return (

<button onClick={() => send('TOGGLE')}>

{current.matches('pending') ? 'Mark done' : 'Mark pending'}

</button>

);

}

This is an example of a simple state, but we can make the state machine as complex as we want. The machine holds our application state and can act as a capable state management alternative to the libraries that we discussed above.

In this article, we explored the general concept of state in React, as well as tools for managing state. We reviewed the built-in options for local component state management, like useState and useReducer. We also explored useContext as a means to store slow-changing application-level state.

Then, we looked into the different external libraries available, including Redux, Mobx, Recoil, Jotai, and Signia. Finally, we looked at state machines as a means to store state and how they can be used in React applications courtesy of the XState library.

I hope you now have a better idea about the state of state management in React and can make an informed decision about which library to use for your next project.

Install LogRocket via npm or script tag. LogRocket.init() must be called client-side, not

server-side

$ npm i --save logrocket

// Code:

import LogRocket from 'logrocket';

LogRocket.init('app/id');

// Add to your HTML:

<script src="https://cdn.lr-ingest.com/LogRocket.min.js"></script>

<script>window.LogRocket && window.LogRocket.init('app/id');</script>

Paige, Jack, Paul, and Noel dig into the biggest shifts reshaping web development right now, from OpenClaw’s foundation move to AI-powered browsers and the growing mental load of agent-driven workflows.

Discover five practical ways to scale knowledge sharing across engineering teams and reduce onboarding time, bottlenecks, and lost context.

Check out alternatives to the Headless UI library to find unstyled components to optimize your website’s performance without compromising your design.

A practical guide to building a fully local RAG system using small language models for secure, privacy-first enterprise AI without relying on cloud services.

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

8 Replies to "The modern guide to React state patterns"

Thanks for this article. Great coverage and you introduced me to some projects that I wasn’t aware of prior.

Very interesting. UseSWR looks really cool but how well does it work across all CRUD actions? How do you invalidate the cache? And what about saving the cache locally instead of in memory as an iPhone has very small memory that gets wiped often.

Thanks!

useSWR will only handle the read operations from the API. Create, Update and Delete you need to handle yourself, but you could easily extract this into a hook of your own or use the native fetch API.

By default useSWR will set up a refreshInterval to refresh the local cache. This property is also configurable, so you can choose your own refreshInterval when you use the useSWR hook. In addition it will revalidate the cache on page focus and network connection by default, which means that you get a lot for free in terms of cache revalidation. In the case that you need to force a cache invalidation you’re provided with a mutate method that you can extract from the useSWR hook that will let useSWR know that something changed and you need to refetch immediately. As for the memory, I believe useSWR utilizes the browser cache instead of actually keeping it in memory.

I’m sorry for being that guy, but claiming that state machines are inspired by Redux is such a backward thing to say. State machines have been around for decades, long before Dan Abramov and Andrew Clark were even born…

If anything Redux is probably inspired from state machines, like the concept of Actions to move from one state to the other.

Why on earth would you be sorry for pointing that out? Thanks for clarifying that obvious error, it was clumsily formulated. In fact, what I meant was that the library XState is reminiscent to redux to the point where you can actually plug in a reducer in xstate and have a state machine with createMachine. I did not mean to imply redux was the source of inspiration for state machines.

Great catch!

The way I see it, React has too many inconsistent ways to deal with state to begin with – hooks added even more new ways to deal with state, and still, new libraries and patterns keep cropping up. There are well over 50 state management libraries, any of which build around or on top of state management in React itself.

In my view, this is all symptomatic of React having incomplete/inconsistent state management to begin with – something that does not seem to get fixed by inventing another pattern or yet another state management library; why else would there still be another idea cropping up every two weeks? It’s because it doesn’t work well, or doesn’t do what developers need or want.

So why don’t they fix it? Well, they can’t, because ultimately that would be a breaking change – and probably a big one, since the problem is not just implementation details, but rather the fundamental concepts; if it were just implementation details, a library would have solved it by now.

A fundamental design change would mean existing component libraries no longer work, at which point React is no longer really React, and the community would likely split into two. This is where programming languages and frameworks get stuck, time and again. They can adjust and adapt – but they can’t truly change.

For an example of state management that actually works, see for example Sinuous – it has a single, consistent, very simple state mechanism that works equally well for local component state and global application state. Refactoring from one to the other literally is a matter of moving lines of code from one place to another. I’ve used it quite a bit, and never felt the need for any state management library or clever patterns – it just works.

Just an example, but I don’t believe the problem is which library or pattern you choose. I believe the problem is inherent to React itself and the state concepts it embodies.

One concept i can’t really wrap my brain around is state vs database storage.

When you want to save the state in a database or a service like firebase, you have to deal with both fetching the data from the database as well as managing state client side.

Do you still need a state manager in that case? Or can you do everything by fetching the required data within the component that needs it? Or only fetch the complete state at loadtime and then handle it all client side?

none of the libraries do what i want, especially now everything I do is in Next or Remix, where complex state lives on the server.

So i built this to do what I need, what do you think, can it replace the complex state management solutions we already have ?