Kirk Gray is the Vice President of Engineering at McGraw-Hill Education. He has extensive experience in the edtech space, including prior roles at Pearson, Schoolrunner, and Blackboard (now part of Anthology).

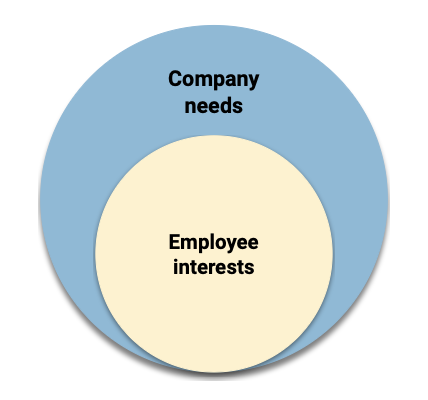

We connected with Kirk to learn more about his approach to building and nurturing teams. Kirk shared his Venn diagram management philosophy and talked about some technical challenges that are specific to education. He also shared insights on leveraging technology to both increase student engagement and give teachers more face time with students.

Well, I think it’s obvious that education is something that’s really important in our society. But teachers have really hard jobs, and the funding climate for schools is tough right now.

There are so many interesting problems to solve in education, and I think technology has a part to play in that. If I ever left edtech, I would have to go to a place where I still felt really good about what I did — where I felt I was doing something that mattered.

Yes, there are some really interesting technical challenges in the space. First, we need to deeply understand what students and teachers need. We need to build tools that let us learn about students, their interests, what they excel at, and where they need extra help. Then, we can provide relevant content and assistance when a student needs it.

There tends to be some level of natural suspicion on the part of educators and administrators about whether we really understand student needs and have their best interests at heart. I think there is this leap of faith that everybody has to make to say, “Hey, we may not get this perfect, but there’s a lot we can do from a technology perspective to help kids.”

Another big challenge, especially in K–12, which is where I primarily work now, is that the buyer is not generally the end user. The buyer is a school district’s IT group, a state board of regents, or a group of superintendents. We sell to them, but the actual people using our software are teachers and students.

It’s always a challenge not only to win in business and make sales, but also to ensure that we’re serving our core constituency. We have to find ways to make good decisions for the business and for the people we serve.

In the past, openness to new technology was an obstacle in edtech as well. But post-pandemic, people have realized that technology is here to stay. It’s no longer a choice of whether or not to use technology in the classroom; it’s a matter of how and how much.

That changes the whole tenor of our conversation as a business. We went from, “How can I convince you to use this digital thing?” to “Let’s partner together to make a digital thing that meets you where you are in the business of teaching kids in your classroom.”

Our usage spiked pretty heavily, probably like most edtech companies. But at McGraw-Hill, we didn’t go all in on the idea of remote learning. We knew that, eventually, teachers would be back in classrooms, so we didn’t want to just think about serving the immediate need.

Ultimately, what teachers really want is more face time with students. When I’m recruiting, I explain that we’re in this business to give a teacher eight minutes back at the end of the day so they can have face time with a student.

Maybe that’s when the student has that aha moment and realizes they can do math or something else. That one moment can change the entire trajectory of a student’s education. Technology isn’t going to give a kid an aha moment, but it can give a teacher the time to create one.

Remote learning forced teachers to start using technology. They realized that some of the tools were pretty good, and they began thinking about other ways to incorporate them.

Our goal is figuring out how to get all students to high-achieving status as soon as possible. When building an educational tool, I always come at it from the lens of, “Hey, how can we make it so a kid wants to do this?”

If a kid has an assignment and uses a tool because they have to, that’s not really a measure of engagement. But we know we’ve built something that’s really resonating with students if they’re choosing to use it because it’s fun, and also because it helped them figure something out that they didn’t know.

People like to achieve things. They like to know that they’re growing. That’s pretty universal. It’s about finding ways for students to have engaging moments, and then also getting the feedback that it’s working. I think Khan Academy does that well.

We have a product called ALEKS that we sell for supplemental, especially math. It does a good job of explaining, “Hey, you did a thing. You learned something. You’ve had an achievement. Now you can build momentum.” Those are the kinds of things that can help get a student engaged in learning.

Before McGraw-Hill, I worked for a company that built solutions primarily for charter management organizations. We had a mobile app that helped teachers do behavior tracking during the five minutes between classes.

But during a school visit, we noticed teachers were so busy fiddling with their phones to track those behaviors that they didn’t have time to talk to students and work on building those important connections.

We were able to reconfigure the app’s workflow into more of a one-click process. This saved the teachers around four minutes, and they could use that time to talk to kids and get to know them. Those little conversations can really make a huge difference.

What’s more, teachers were using the app seven times a day, so suddenly we were saving them close to a half hour a day. It took just a two-hour code change to address a problem that we never even knew existed until we saw it firsthand.

When I started here, we were very much in the business of building widgets, as many companies are. It was like, “Here’s the thing I need. Here’s the binder. Can you go build it? When can you have it done?”

I think we’ve really matured those relationships where we now take a step back and consider what problem we’re solving, who we are serving, and exactly what the user does when they sit down in front of the computer.

By building trust with our business partners and product management folks, we now have a lot more freedom to build something that doesn’t just tick the boxes, but advances us as an organization, helps us do the next thing better, or helps us solve this next class of problems more easily.

I think there are two big concepts that run through business school. The first is competitive advantage, and the second is this sort of allocation of scarce resources.

When we combine those two things and use them to frame our decisions, we start asking:

I think that’s a really important frame because in this industry there’s a lot of stuff that companies do just to get parity.

I always tell new employees that there’s this Venn diagram of things the company needs to succeed, and then there’s the things you want to do. Ideally, you want one circle. That’s my entire management philosophy: How do we manage to make that Venn diagram into a circle?

When I joined McGraw-Hill, I noticed that what it meant to be a senior engineer was completely different based on the team or group. So we put together a career ladder to give people a path. I think its existence tells people we care and their work matters.

Then, instead of focusing on annual goals, we ask, “What competency are you trying to master?” From there, we can create a goal that is maybe a month long and really focused. Then, we can check in on it during one-on-ones and help with some strategies.

We’re a learning organization, so we want to be intentional about making time and space to learn. I’ve done a lot of unofficial learning and development with my group. I tell my team, “I want to build communities of practice where people have time, and that’s expected, and it isn’t a detriment to the work.”

There’s always two threads: one about getting stuff done and one about getting better so that the next thing you do is a little easier, a little faster, and a little more fun.

Education is a very calendar-based business, and we have a lot of pressure to deliver, so we have to consider innovation in our planning. In the career ladder that I mentioned earlier, one of the competencies that we reward is innovation.

We want to make sure there’s not an “innovation” team and an “everybody else” team. Just having an R&D team is a huge antipattern for me. Instead, we want to make sure that innovation is part of everyone’s job.

Frankly, innovation often comes from some of the most junior people. They will ask the most questions about why we do things a particular way.

Technology skills are obviously important, but if someone has the right mindset around growth, I think the technology stuff sorts itself out. It’s really about getting the right attitude.

There are three things I look for:

I believe that the people we serve are the most important customers out there because they’re going to end up being our society someday. It’s important that we care deeply about that.

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

Get to know RxJS features, benefits, and more to help you understand what it is, how it works, and why you should use it.

Explore how to effectively break down a monolithic application into microservices using feature flags and Flagsmith.

Native dialog and popover elements have their own well-defined roles in modern-day frontend web development. Dialog elements are known to […]

LlamaIndex provides tools for ingesting, processing, and implementing complex query workflows that combine data access with LLM prompting.