In JavaScript, you’ve probably worked with objects quite a bit. You’ve created and modified them, maybe added some methods, and accessed their properties.

But have you ever wondered how objects can share behaviors, or why specific methods like toString() are available on every object you create, even though you didn’t define them yourself? That’s where JavaScript prototypes come in.

In this guide, we’ll explore what prototypes are, how the prototype chain works, and how to use this chain to create inheritance between objects. We’ll also look at the modern class syntax introduced in ES6, which serves as a cleaner way to work with prototypes.

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

A JavaScript prototype is the mechanism that allows one object to inherit properties and methods from another. This is known as prototype-based inheritance and is a fundamental part of how JavaScript works.

Where it can get a bit confusing is how this all works under the hood — particularly the distinction between an object’s internal [[Prototype]] and the prototype property. Let’s break that down.

[[Prototype]] vs prototype propertyAn object’s prototype, often called [[Prototype]], is an internal reference that allows one object to access properties and methods defined on another object. This enables behavior to be inherited through what’s known as the prototype chain.

Let’s see how this works with a plain object:

const book = {

title: 'book_one',

genre: 'sci-fi',

author: 'Ibas Majid',

bookDetails: function () {

return `Name: ${this.author} | Title: ${this.title} | Genre: ${this.genre}.`;

},

};

console.log(book.bookDetails());

// Output: "Name: Ibas Majid | Title: book_one | Genre: sci-fi."

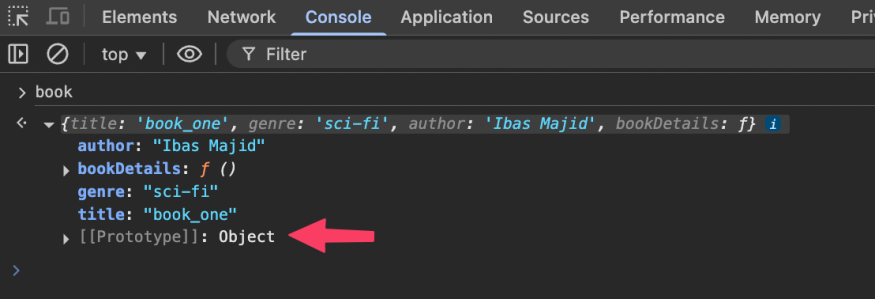

If you inspect the object in the browser DevTools, you’ll notice it has an internal [[Prototype]], which links to additional properties and methods provided by JavaScript’s built-in Object:

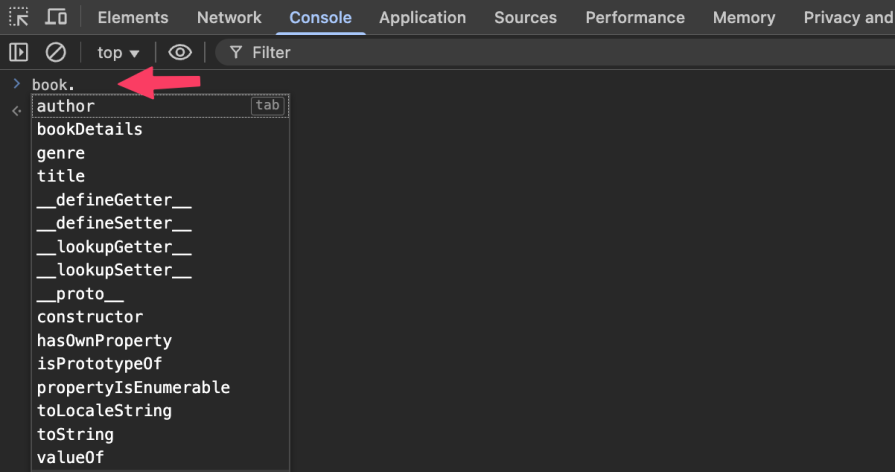

Now, if you type book. in the browser console, you’ll see not only the properties and methods we defined, but also built-in methods like toString(), hasOwnProperty(), and more:

This happens because when an object is created using literal syntax {}, like the book object, JavaScript automatically sets its internal [[Prototype]] to reference Object.prototype. That’s where these built-in methods come from; they’re inherited through the prototype chain.

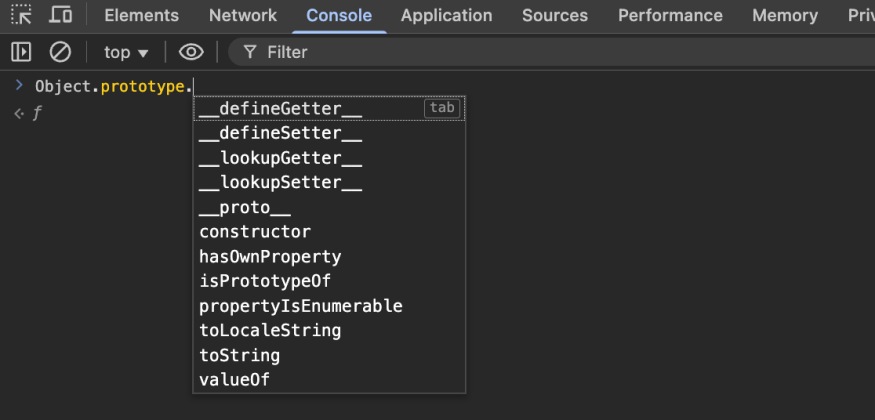

While these methods are defined on Object.prototype (i.e., the prototype property of the object constructor), the book object gains access to them via its internal [[Prototype]] link. If you type Object.prototype. in the console, you’ll see the same methods available to book, thanks to this inheritance:

In our book object, we didn’t explicitly define a toString() method, yet calling it still returns a value:

console.log(book.toString()); // [object Object]

When a method or property is accessed on an object, JavaScript first checks if it exists on that object directly. Since toString() isn’t defined on the book object, it follows the internal [[Prototype]] reference, which points to Object.prototype and finds the method there.

If the method isn’t found on the Object.prototype, JavaScript continues up the prototype chain until it either finds the method or reaches null, which marks the end of the chain. If the search reaches null without success, JavaScript throws an error for methods or returns undefined for properties:

console.log(book.toNotAvailable()); // Uncaught TypeError: book.toNotAvailable is not a function

The prototype chain in this case looks like this:

book → Object.prototype → null

As seen, the Object.prototype sits at the top of the prototype chain, and every object in JavaScript ultimately inherits from it.

Constructor functions allow us to create reusable templates for generating similar objects. Rather than repeatedly writing the same object structure, we define a function that initializes properties, and JavaScript uses the new keyword to create a new object instance from it.

In the example below, the Book function serves as a blueprint for creating multiple book objects:

function Book(title, genre, author) {

this.title = title;

this.genre = genre;

this.author = author;

}

For shared behavior, such as a method to display book details, it is more efficient to define the method on the constructor’s prototype. Just like with Object.prototype, any methods defined on a constructor’s prototype, such as Book.prototype in this case, are inherited by all instances without each having its own copy:

Book.prototype.bookDetails = function () {

return `Name: ${this.author} | Title: ${this.title} | Genre: ${this.genre}.`;

};

Now, using the new keyword, we can create multiple book objects:

const book1 = new Book('book_one', 'sci-fi', 'Ibas Majid');

const book2 = new Book('book_two', 'fantasy', 'Alice M.');

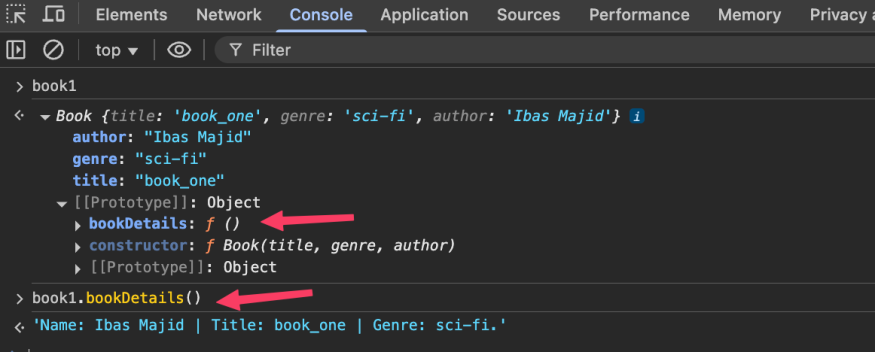

Both book1 and book2 share the bookDetails method via Book.prototype. When you inspect book1 in the console and call book1.bookDetails(), you’ll see that the method is not a direct property of book1, but is inherited through the constructor’s prototype:

The prototype chain in this case looks like this:

book1 → Book.prototype → Object.prototype → null

Just like custom constructor functions, built-in objects also inherit properties and methods through their respective prototypes. For example, arrays inherit from Array.prototype, and date objects from Date.prototype. Ultimately, all prototype chains lead back to Object.prototype, which sits at the top:

dateObj → Date.prototype → Object.prototype → null arrayObj → Array.prototype → Object.prototype → null

JavaScript provides essential methods for interacting with an object’s prototype:

Object.getPrototypeOf(obj)This method retrieves the prototype of an object. It is useful when you want to inspect or confirm the inheritance structure of an object:

function Book(...) {

// ...

}

const book1 = new Book(...);

console.log(Object.getPrototypeOf(book1)); // Outputs Book.prototype

In the code, we’ve used Object.getPrototypeOf(book1) to retrieve the prototype, confirming that book1 inherits from Book.prototype.

Object.setPrototypeOf(obj, proto)This method allows you to change the prototype of an existing object. The following code defines customProto with a describe method and sets it as the prototype of the book1:

function Book(...) {

// ...

}

const book1 = new Book(...);

const customProto = {

describe() {

return `Title: ${this.title}`;

},

};

Object.setPrototypeOf(book1, customProto);

console.log(book1.describe()); // Outputs: 'Title: book_one'

Now, book1 inherits from customProto and can use the describe method. This operation overrides its original prototype chain.

Object.create(proto)This method allows you to create a new object and set its prototype explicitly. The following code creates newBook, which inherits from book1:

function Book(...) {

// ...

}

const book1 = new Book(...);

// Create a new object that inherits from the book1

const newBook = Object.create(book1);

console.log(newBook.author); // Outputs: 'Ibas Majid'

Accessing newBook.author pulls the value from the book1 via prototype inheritance.

A key strength of prototypes is their ability to create inheritance hierarchies. For instance, suppose we want to reuse features from our Book constructor in a new constructor called Journal. Rather than building Journal from scratch, we can extend Book so that Journal inherits its properties and methods.

Since the Book already includes properties like title, genre, and author, we’ll create a Journal to inherit these while also adding a new year property.

The code would look like this:

// Constructor function

function Book(title, genre, author) {

// ...

}

Book.prototype.bookDetails = function () {

// ...

};

function Journal(title, genre, author, year) {

Book.call(this, title, genre, author);

this.year = year;

}

const journal1 = new Journal(

'Journal_one',

'technology',

'John Marcus',

'2020'

);

In this example, the Journal constructor uses Book.call() to inherit the title, genre, and author properties from Book, while introducing its own year property. This allows the journal1 object to carry over the properties defined in the Book, making it easy to reuse and extend functionality without duplicating code.

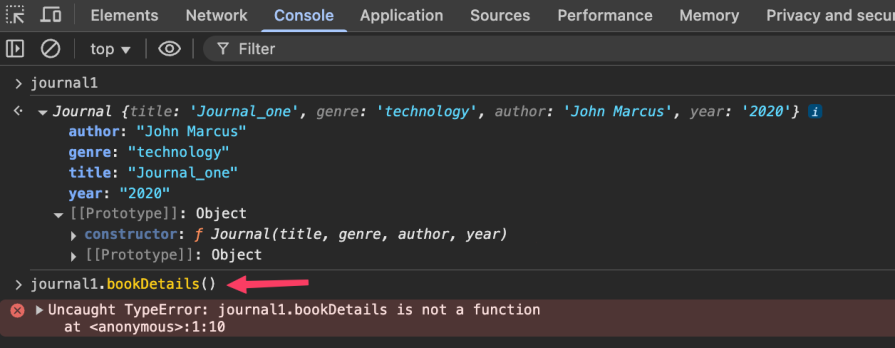

Accessing journal1 in the console returns the expected values. However, if you try to call a method from the parent constructor’s prototype, such as bookDetails(), it will result in an error:

This happens because while Book.call() copies the properties, it does not link the Journal to Book prototype, meaning methods defined on Book.prototype are not inherited by default.

To ensure that instances of Journal can access methods defined on the Book.prototype, we need to establish a connection between their prototypes. Specifically, we link Journal.prototype to Book.prototype, so that methods like bookDetails become available to all Journal instances through inheritance.

To set up this prototype chain, use Object.setPrototypeOf() immediately after defining the Journal constructor function, but before creating any instances:

// Constructor function

function Journal(title, genre, author, year) {

// ...

}

// Link Journal.prototype to the Book.prototype

Object.setPrototypeOf(Journal.prototype, Book.prototype);

// Create an instance of Journal

const journal1 = new Journal(...);

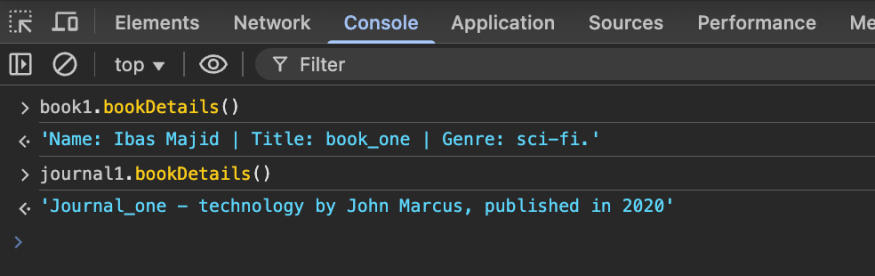

Now, journal1 has access to both its properties and any methods available on the Book.prototype, like bookDetails.

To incorporate the year property in the Journal, we can override the inherited bookDetails() method with a customized version. This ensures that Journal instances display complete details while preserving their prototype connection to Book.

Add the following code before creating any Journal instances:

// Override bookDetails to include year

Journal.prototype.bookDetails = function () {

return `${this.title} - ${this.genre} by ${this.author}, published in ${this.year}`;

};

Now, when you call bookDetails() on both the book1 instance and journal1 instance, each will return the appropriate message based on its properties:

ES6 introduces a more convenient class syntax for creating constructor functions and setting up prototype chains. However, under the hood, JavaScript still uses the prototype-based inheritance model we explored above.

Here’s how it works, starting with a simple class definition:

class Book {

constructor(...) {

// properties assigned here

}

// other methods here...

}

Using the ES6 class keyword, we define a blueprint for creating object instances. The class can include a constructor method for property initialization, along with additional methods that are automatically added to the prototype.

Rewriting our earlier Book constructor with ES6 syntax:

class Book {

constructor(title, genre, author) {

this.title = title;

this.genre = genre;

this.author = author;

}

bookDetails() {

return `Name: ${this.author} | Title: ${this.title} | Genre: ${this.genre}.`;

}

}

const book1 = new Book('book_one', 'sci-fi', 'Ibas Majid');

This syntax is more convenient, as methods are automatically added to the prototype—no manual setup is required. You can verify this in your browser’s DevTools.

To create a subclass from our existing Book class, we use the extends keyword. This tells JavaScript that the new child class should inherit properties and methods from the parent class.

Let’s rewrite our traditional prototype-based Journal constructor using ES6 class syntax. Add the following code after the Book class definition:

// Book sub class

class Journal extends Book {

constructor(title, genre, author, year) {

super(title, genre, author);

this.year = year;

}

}

// instantiate Journal

const journal1 = new Journal(

'Journal_one',

'technology',

'John Marcus',

'2020'

);

In this example, Journal extends Book, automatically inheriting its properties and methods. Within the Journal constructor, we use super() to call the parent’s constructor and initialize the title, genre, and author, followed by defining the year property specific to Journal.

With this setup, there is no need to manually establish the prototype chain. ES6 class inheritance takes care of it, ensuring that instances of Journal have access to methods defined on Book.prototype. You can confirm this using your browser’s DevTools.

Just like in the prototype-based approach, we can override the bookDetails() method in the Journal class to include the year. Here’s how:

class Journal extends Book {

// constructor

bookDetails() {

return `${this.title} - ${this.genre} by ${this.author}, published in ${this.year}`;

}

}

Now, calling journal1.bookDetails() will return a message that includes all the properties, including the year.

Prototypes are a core feature of JavaScript, enabling objects to inherit properties and methods from other objects. By understanding the prototype chain, utilizing constructor functions, and leveraging the power of ES6 classes, you can write more efficient and maintainable code. Whether you’re working with plain objects, traditional constructors, or modern class-based syntax, a solid grasp of prototypes is essential for effective JavaScript programming.

If you found this guide helpful, feel free to share it online. Questions or thoughts? Drop them in the comments. I’d love to hear from you.

Paige, Jack, Paul, and Noel dig into the biggest shifts reshaping web development right now, from OpenClaw’s foundation move to AI-powered browsers and the growing mental load of agent-driven workflows.

Discover five practical ways to scale knowledge sharing across engineering teams and reduce onboarding time, bottlenecks, and lost context.

Check out alternatives to the Headless UI library to find unstyled components to optimize your website’s performance without compromising your design.

A practical guide to building a fully local RAG system using small language models for secure, privacy-first enterprise AI without relying on cloud services.

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now