Editor’s note: This article was last updated by Lewis Cianci on 26 May 2023 to update the C# code based on the latest version, at the time of writing. Check out the .NET 7 docs for more information

Generating clients for APIs is a great way to reduce the amount of work you have to do when you’re building a project. Why handwrite that code when it can be autogenerated for you quickly and accurately by a tool like NSwag? To quote the docs:

“The NSwag project provides tools to generate OpenAPI specifications from existing ASP.NET Web API controllers and client code from these OpenAPI specifications. The project combines the functionality of Swashbuckle (OpenAPI/Swagger generation) and AutoRest (client generation) in one toolchain.”

There are some great posts out there that show you how to generate the clients with NSwag using an nswag.json file directly from a .NET project. But, what if you want to use NSwag purely for its client generation capabilities? You may have an API written with another language/platform that exposes a Swagger endpoint that you simply wish to create a client for. How do you do that?

Also, if you want to specifically customize the clients you’re generating, you may find yourself struggling to configure that in nswag.json. In that case, it’s possible to hook into NSwag directly to do this with a simple .NET console app.

In pursuit of answers to the questions above, this post will:

Before proceeding, note that you will need both Node.js and the .NET SDK installed.

Jump ahead:

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

We’ll start off by creating an API that exposes a Swagger/OpenAPI endpoint. While we’re doing that, we’ll create a TypeScript React app that we’ll use later on.

First, drop to the command line and enter the following commands, which use the .NET SDK, Node, and the create-react-app package:

mkdir src cd src npx create-react-app client-app --template typescript mkdir server-app cd server-app dotnet new webapi -o API cd API dotnet add package NSwag.AspNetCore

We now have a .NET API with a dependency on NSwag. We’ll start to use it by replacing the Startup.cs that’s been generated with the following:

using API;

var builder = WebApplication.CreateBuilder(args);

const string ALLOW_DEVELOPMENT_CORS_ORIGINS_POLICY = "AllowDevelopmentSpecificOrigins";

const string LOCAL_DEVELOPMENT_URL = "http://localhost:3000";

// Add services to the container.

builder.Services.AddControllers();

builder.Services.AddCors(options =>

{

options.AddPolicy(name: ALLOW_DEVELOPMENT_CORS_ORIGINS_POLICY,

builder =>

{

builder.WithOrigins(LOCAL_DEVELOPMENT_URL)

.AllowAnyMethod()

.AllowAnyHeader()

.AllowCredentials();

});

});

// Register the Swagger services.

builder.Services.AddSwaggerDocument();

// Build the application.

var app = builder.Build();

// Configure the HTTP request pipeline.

if (app.Environment.IsDevelopment())

{

app.UseDeveloperExceptionPage();

}

else

{

app.UseExceptionHandler("/Error");

app.UseHsts();

app.UseHttpsRedirection();

}

app.UseDefaultFiles();

app.UseStaticFiles();

app.UseRouting();

app.UseAuthorization();

// Register the Swagger generator and the Swagger UI middlewares.

app.UseOpenApi();

app.UseSwaggerUi3();

if (app.Environment.IsDevelopment())

{

app.UseCors(ALLOW_DEVELOPMENT_CORS_ORIGINS_POLICY);

}

app.MapControllers();

app.Run();

The significant changes to note in the above Startup.cs are:

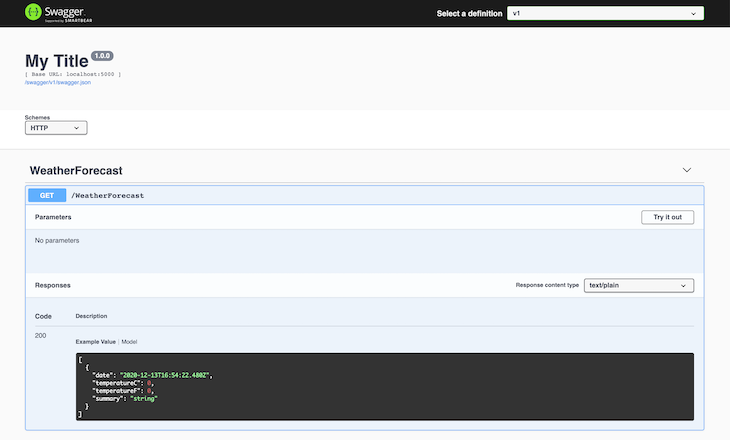

UseOpenApi and UseSwaggerUi3. NSwag will automatically create Swagger endpoints in your application for all your controllers. The .NET template ships with a WeatherForecastControllerBack in the root of our project we’re going to initialize an npm project. We’re going to use this to put in place a number of handy npm scripts that will make our project easier to work with. So we’ll npm init and accept all the defaults.

Now, add some dependencies that our scripts will use: npm install cpx cross-env npm-run-all start-server-and-test--save.

Let’s also add some scripts to our package.json:

"scripts": {

"postinstall": "npm run install:client-app && npm run install:server-app",

"install:client-app": "cd src/client-app && npm install",

"install:server-app": "cd src/server-app/API && dotnet restore",

"build": "npm run build:client-app && npm run build:server-app",

"build:client-app": "cd src/client-app && npm run build",

"postbuild:client-app": "cpx \"src/client-app/build/**/*.*\" \"src/server-app/API/wwwroot/\"",

"build:server-app": "cd src/server-app/API && dotnet build --configuration release",

"start": "run-p start:client-app start:server-app",

"start:client-app": "cd src/client-app && npm start",

"start:server-app": "cross-env ASPNETCORE_URLS=http://127.0.0.1:5000 ASPNETCORE_ENVIRONMENT=Development dotnet watch --project src/server-app/API run --no-launch-profile"

}

Let’s walk through what the above scripts provide us with. Running npm install in the root of our project will not only install dependencies for our root package.json. Thanks to our postinstall, install:client-app, and install:server-app scripts, it will install the React app and .NET app dependencies as well.

Running npm run build will build our client and server apps, and running npm run start will start both our React app and our .NET app. Our React app will be started at http://localhost:3000. Our .NET app will be started at http://localhost:5000 (some environment variables are passed to it with cross-env).

Once npm run start has been run, find a Swagger endpoint at http://localhost:5000/swagger:

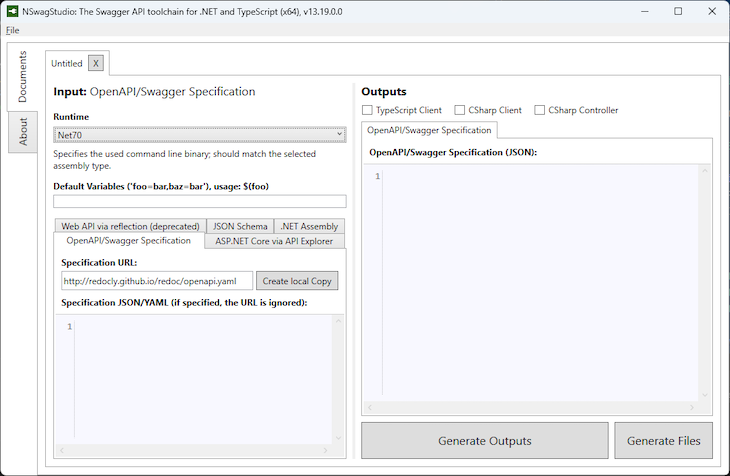

NSwagStudio makes it easy to generate API code in your React app. NSwagStudio was developed by the same team as NSwag, so it fits naturally into an existing NSwag workflow. Because you can save NSwag projects and check them in to source control as well, they can be an easy way for other developers to understand how your specific API project works.

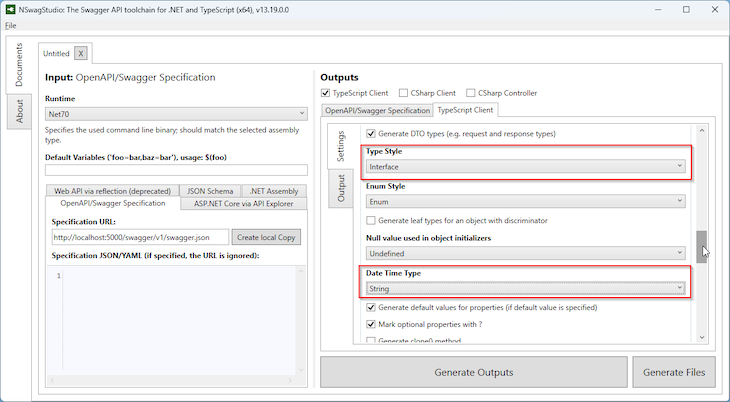

Grab the latest version of NSwagStudio here, and follow through with the installer. In the end, open up NSwagStudio, and you should see something like this:

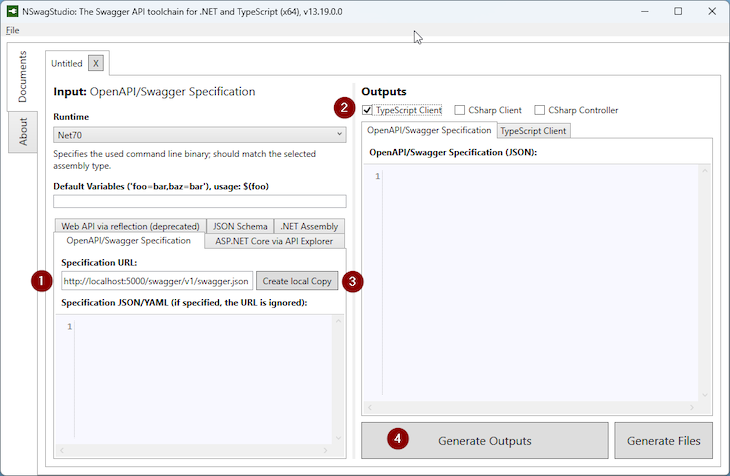

In our case, we want to:

Next, click on the TypeScript Client tab, and then on Settings. Change the Type Style to Interface, and Date Time Type to String:

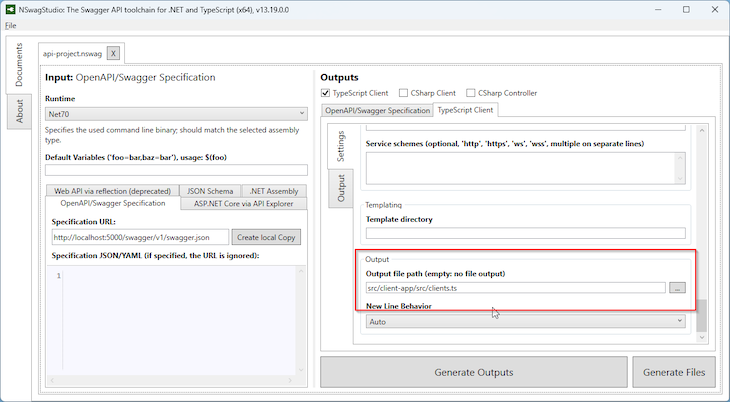

Then, set the output file path to src/client-app/src/clients.ts:

Finally, save the NSwag project to the root of your project, then click Generate Outputs, and Generate Files. This will generate your API code for use by the React app.

Sometimes you may need more control over your API generation, or you may want to do it as part of a CI/CD build process. In these times, you can adopt a more programmatic approach to your API generation. To do so, we can put together the console app that will generate our typed clients.

Skip this section if you’ve already configured your project via NSwagStudio, and are happy with that approach! Otherwise, you’ll be doubling up on your work.

To do this, first open a command prompt in your project root and type the following:

cd src/server-app dotnet new console -o APIClientGenerator cd APIClientGenerator dotnet add package NSwag.CodeGeneration.CSharp dotnet add package NSwag.CodeGeneration.TypeScript dotnet add package NSwag.Core

We now have a console app with dependencies on the code generation portions of NSwag. Let’s change up Program.cs to make use of this:

// See https://aka.ms/new-console-template for more information

using NJsonSchema.CodeGeneration.TypeScript;

using NSwag;

using NSwag.CodeGeneration.CSharp;

using NSwag.CodeGeneration.TypeScript;

Console.WriteLine("Hello, World!");

if (args.Length != 3)

throw new ArgumentException("Expecting 3 arguments: URL, generatePath, language");

var url = args[0];

var generatePath = Path.Combine(Directory.GetCurrentDirectory(), args[1]);

var language = args[2];

if (language != "TypeScript" && language != "CSharp")

throw new ArgumentException("Invalid language parameter; valid values are TypeScript and CSharp");

if (language == "TypeScript")

await GenerateTypeScriptClient(url, generatePath);

else

await GenerateCSharpClient(url, generatePath);

async static Task GenerateTypeScriptClient(string url, string generatePath) =>

await GenerateClient(

document: await OpenApiDocument.FromUrlAsync(url),

generatePath: generatePath,

generateCode: (OpenApiDocument document) =>

{

var settings = new TypeScriptClientGeneratorSettings();

settings.TypeScriptGeneratorSettings.TypeStyle = TypeScriptTypeStyle.Interface;

settings.TypeScriptGeneratorSettings.TypeScriptVersion = 3.5M;

settings.TypeScriptGeneratorSettings.DateTimeType = TypeScriptDateTimeType.String;

var generator = new TypeScriptClientGenerator(document, settings);

var code = generator.GenerateFile();

return code;

}

);

async static Task GenerateCSharpClient(string url, string generatePath) =>

await GenerateClient(

document: await OpenApiDocument.FromUrlAsync(url),

generatePath: generatePath,

generateCode: (OpenApiDocument document) =>

{

var settings = new CSharpClientGeneratorSettings

{

UseBaseUrl = false

};

var generator = new CSharpClientGenerator(document, settings);

var code = generator.GenerateFile();

return code;

}

);

async static Task GenerateClient(OpenApiDocument document, string generatePath, Func<OpenApiDocument, string> generateCode)

{

Console.WriteLine($"Generating {generatePath}...");

var code = generateCode(document);

await System.IO.File.WriteAllTextAsync(generatePath, code);

}

We’ve created a simple .NET console application that creates TypeScript and C# clients for a given Swagger URL. It expects three arguments:

url: The URL of the swagger.json file for which to generate a clientgeneratePath: The path where the generated client file should be placed, relative to this projectlanguage: The language of the client to generate; valid values are “TypeScript” and “CSharp”To create a TypeScript client with it, we’d use the following command:

dotnet run --project src/server-app/APIClientGenerator http://localhost:5000/swagger/v1/swagger.json src/client-app/src/clients.ts TypeScript

However, for this to run successfully, we first have to ensure the API is running. It would be great if we had a single command we could run that would:

Let’s make that!

In the root of the project, we’re going to add the following scripts:

"generate-client:server-app": "start-server-and-test generate-client:server-app:serve http-get://localhost:5000/swagger/v1/swagger.json generate-client:server-app:generate",

"generate-client:server-app:serve": "cross-env ASPNETCORE_URLS=http://*:5000 ASPNETCORE_ENVIRONMENT=Development dotnet run --project src/server-app/API --no-launch-profile",

"generate-client:server-app:generate": "dotnet run --project src/server-app/APIClientGenerator http://localhost:5000/swagger/v1/swagger.json src/client-app/src/clients.ts TypeScript",

Let’s walk through what’s happening here. Running npm run generate-client:server-app will use the start-server-and-test package to spin up our server-app by running the generate-client:server-app:serve script.

start-server-and-test waits for the Swagger endpoint to start responding to requests. When it does start responding, start-server-and-test runs the generate-client:server-app:generate script, which runs our APIClientGenerator console app and provides it with the URL where our Swagger can be found, the path of the file to generate, and the language of “TypeScript.”

If you wanted to generate a C# client — say, if you were writing a Blazor app — then you could change the generate-client:server-app:generate script as follows:

"generate-client:server-app:generate": "dotnet run --project src/server-app/ApiClientGenerator http://localhost:5000/swagger/v1/swagger.json clients.cs CSharp",

Now, let’s consume our generated client from within our React app. If you’ve just skipped the above section on how to programmatically generate our API clients, this is the part where you should rejoin us 😊

First, let’s run the npm run generate-client:server-app command. It creates a clients.ts file, which nestles nicely inside our client-app. We’re going to exercise that in a moment.

First, let’s enable proxying from our client-app to our server-app by following the instructions in the create-react-app docs and adding the following to our client-app/package.json:

"proxy": "http://localhost:5000"

Now let’s start our apps with npm run start. Then, replace the contents of App.tsx with:

import React from "react";

import "./App.css";

import { WeatherForecast, WeatherForecastClient } from "./clients";

function App() {

const [weather, setWeather] = React.useState<WeatherForecast[] | null>();

React.useEffect(() => {

async function loadWeather() {

const weatherClient = new WeatherForecastClient(/* baseUrl */ "");

const forecast = await weatherClient.get();

setWeather(forecast);

}

loadWeather();

}, [setWeather]);

return (

<div className="App">

<header className="App-header">

{weather ? (

<table>

<thead>

<tr>

<th>Date</th>

<th>Summary</th>

<th>Centigrade</th>

<th>Fahrenheit</th>

</tr>

</thead>

<tbody>

{weather.map(({ date, summary, temperatureC, temperatureF }) => (

<tr key={date}>

<td>{new Date(date).toLocaleDateString()}</td>

<td>{summary}</td>

<td>{temperatureC}</td>

<td>{temperatureF}</td>

</tr>

))}

</tbody>

</table>

) : (

<p>Loading weather...</p>

)}

</header>

</div>

);

}

export default App;

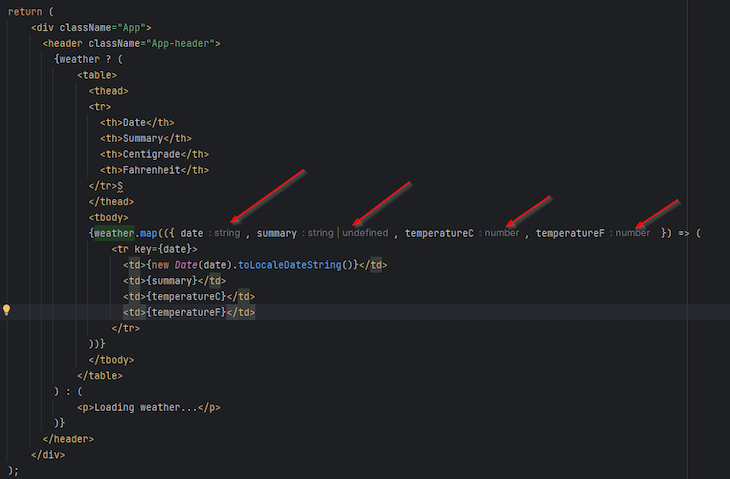

Inside the React.useEffect above, we create a new instance of the autogenerated WeatherForecastClient. We then call weatherClient.get(), which sends the GET request to the server to acquire the data and provides it in a strongly typed fashion. get() returns an array of WeatherForecast. This is then displayed on the page like so:

We loaded data from the server using our autogenerated client. We’re reducing the amount of code we have to write and we’re reducing the likelihood of errors.

Finally, if we inspect our App.tsx, we can see that our app is actually aware of the types that the API has provided:

These types are automatically loaded for TypeScript, and are available for use in our project.

Occasionally when you are using NSwag to generate your APIs, you may hear about terms like NSwag Schema. When I think of schemas, I think of databases or XML documents with schema elements.

An NSwag Schema is slightly different. It’s a JSON file that is produced automatically by NSwag and defines the endpoints within our API, and what data types these APIs return. It’s very helpful because it means we can use the Swagger API explorer, but also because that’s how NSwagStudio (or other tools) generate our API code. Hopefully, that helps you to understand Swagger Schemas within the broader context of NSwag.

It wasn’t that long ago that we would have to write our API code by hand, and manually update it whenever there was a change. Thankfully, that’s in the past now with tools like Swagger, OpenAPI, and NSwag. In this article, we’ve shown how to use NSwagStudio to generate code in a more visual way, while also showing how to programmatically generate API code for more advanced use cases.

The code samples in this article are also based in .NET 7, for your ease of use.

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings — compatible with all frameworks, and with plugins to log additional context from Redux, Vuex, and @ngrx/store.

With Galileo AI, you can instantly identify and explain user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

Modernize how you understand your web and mobile apps — start monitoring for free.

Compare the top AI development tools and models of March 2026. View updated rankings, feature breakdowns, and find the best fit for you.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the March 11th issue.

Buying AI tools isn’t enough. Engineering teams need AI literacy programs to unlock real productivity gains and avoid uneven adoption.

If your AI app or agent works perfectly in development but falls apart in production, you’re not alone. In a […]

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now