In a single day, 385,000 babies are born, the sun evaporates over a trillion tons of water off the surface of the ocean, and fifteen new stable versions of Angular are released. Okay, that’s an exaggeration (not the babies and evaporation bit!), but the Angular release cycle these days is certainly quick — and it’s not slowing down.

This latest update brings a couple of notable quality-of-life improvements. First of all, redirects within Angular can now occur by way of a RedirectCommand, which allows greater control over how a redirect occurs and easier implementation of best practices. Secondly, we can now declare variables within the view themselves, which can be helpful.

How do we use these features? Let’s take a look.

RedirectCommand classWhy is redirecting such a headline feature in Angular 18? We’re literally just shifting from one page to another. But navigation — something that we take for granted when we click on a link — is deceptively simple.

Consider a simple website with some trivial routes:

/ — The root page of the application/admin — Where administrators can see everyone’s journal entries/write — Where users write journal entriesEveryone should be able to access the application root, including anonymous users. But should everyone be able to access the admin route? Of course not — that’s just a cybersecurity risk waiting to happen.

What about if users are on the write route, and they try to navigate to the root route? That’s fine from a security perspective, but they might lose what they’re writing! Ideally, we’d want to show a confirmation dialog before performing that routing operation.

Within the Angular nomenclature, these actions essentially boil down to the following actions:

canMatch: Sometimes, more than one route can match a given path. If a user is an admin, they should see the admin write route. Otherwise, they should see the normal write pagecanActivate: If a route is allowed to be activated or not. For example, the write route should only be accessible if the user is logged incanDeactivate: If a user can navigate away from a route. Typically used to show a dialog box when navigating away from a page with changed dataTo help understand the power of RedirectCommand, let’s create a sample application called Journalpedia that has some of this basic routing functionality. Journalpedia will look very plain, and that’s okay, because the focus of this article is on routing and not visual appeal.

For the purposes of this article, we’ll have our app.component.html contain a router-outlet, but it will also contain a Login Simulator that lets us change between user types on the fly. The idea is that we can route to anywhere on the test site and still be able to change between accounts:

<router-outlet></router-outlet> <div style="bottom: 0; right: 0; height: 200px; width: 200px; background-color: wheat; position: fixed"> <app-login-simulator></app-login-simulator> </div>

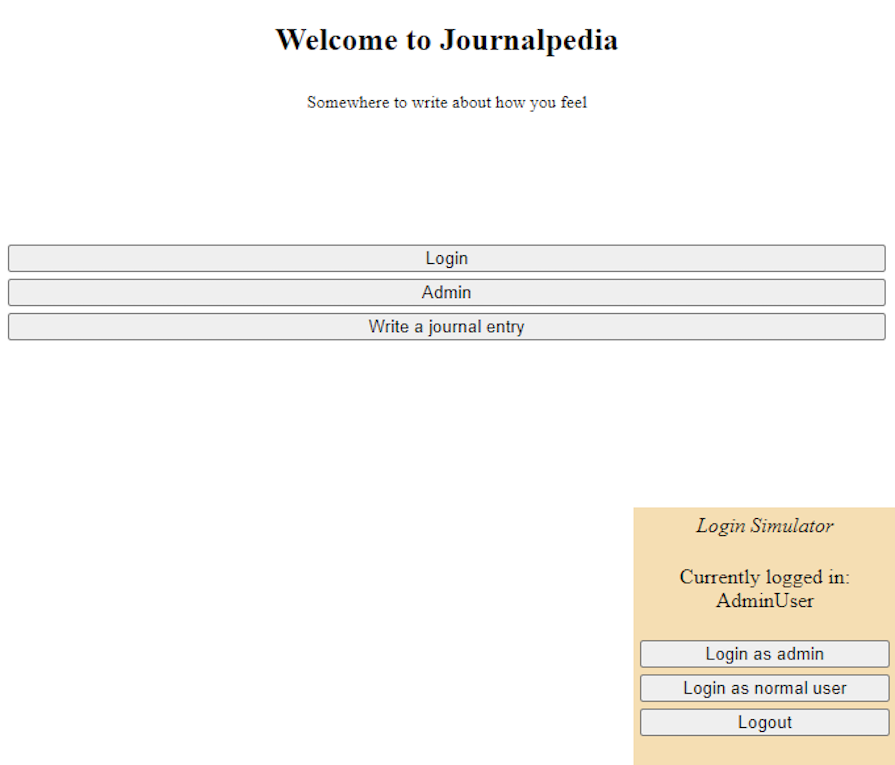

The front page of our app will look like this:

Our app has three buttons. Typically, we wouldn’t display the Admin or Write a journal entry buttons because we don’t want users to try to click on them before logging in, but in this article we’ll show them anyway so we can see how route guards and activation work.

Normally, users could log in or change their logins at any time, but we don’t have a fully fledged authentication system in place. Instead, we can click on our Login Simulator to simulate a user logging in.

RedirectCommand class?To clarify, redirect functionality has long been part of Angular’s feature set. So why did Angular 18 introduce an entirely new class? Let’s see how redirection occurs in Angular apps today to see why RedirectCommand is an improvement.

Typically, routes within an application like this would look like the following:

export const routes: Routes = [

{

path: '',

component: HomeComponent,

},

{

path: 'admin',

component: AdminComponent,

canActivate: [() => {

const router = inject(Router);

const auth = inject(AuthenticationService);

if (auth.userLogin$.value == LoginType.AdminUser){

return true;

}

else{

router.navigate(['/unauthorized']);

return false;

}

}],

},

{

path: 'write',

component: WriteComponent,

canActivate: [() => {

const router = inject(Router);

const auth = inject(AuthenticationService);

if (auth.userLogin$.value != undefined) {

return true;

} else {

router.navigate(['/unauthorized']);

return false;

}

}]

},

{

path: 'unauthorized',

component: UnauthorizedComponent

}

];

The crux of the routing operation here is to check that a user is of the correct type, and confirm that the navigation can happen. Otherwise, redirect to the unauthorized page.

For most applications, this is fine, but it introduces a dependency on returning either a true or false value from the guard. If we’re returning true, the navigation will complete, but if it returns false, then the navigation will just not occur. Sometimes, this can cause developers and consumers alike to become confused at the lack of routing occurring.

Fortunately, we can return a URL tree directly from within our canActivate function, specifying a direct path to another page, like so:

{

path: 'admin',

component: AdminComponent,

canActivate: [() => {

const router = inject(Router);

const auth = inject(AuthenticationService);

if (auth.userLogin$.value == LoginType.AdminUser){

return true;

}

return router.parseUrl('/unauthorized')

}],

}

This is a better pattern for two reasons: first, we’re not flat-out rejecting the navigation. Second, something will always occur — either the navigation will succeed, or it will return an alternative route.

The only wrinkle in this approach is that we can’t pass extra NavigationExtra properties in parseUrl.

NavigationExtra properties pave the way for a bunch of advanced routing scenarios — for example, how query parameters should be handled, whether a location change should be skipped or not. They also give us the opportunity to pass data to the navigated page via the state property.

Fortunately, that’s exactly where RedirectCommand comes in. RedirectCommand accepts a UrlTree, but also accepts NavigationExtra properties. We can redirect to another page and use NavigationExtra properties at the same time. Because it’s a new class, it doesn’t break any existing functionality, which is great!

So, our admin route becomes:

{

path: 'admin',

component: AdminComponent,

canActivate: [() => {

const router = inject(Router);

const auth = inject(AuthenticationService);

if (auth.userLogin$.value == LoginType.AdminUser) {

return true;

}

return new RedirectCommand(router.parseUrl('/unauthorized'), {

skipLocationChange: true, state: {

loginDuringAuth: auth.userLogin$.value

}

})

}],

},

With this, we don’t return false from the canActivate function, and we can take full advantage of the NavigationExtra superpowers. In this example, we observe something that happened during the routing operation and put that in the state variable.

Within the constructor for the unauthorized page, we can retrieve this state variable, like so:

constructor(private _location: Location, private _router: Router) {

console.log(this._router.getCurrentNavigation()?.extras.state);

this.loginDuringAuth.set(_router.getCurrentNavigation()?.extras?.state?.['loginDuringAuth']);

}

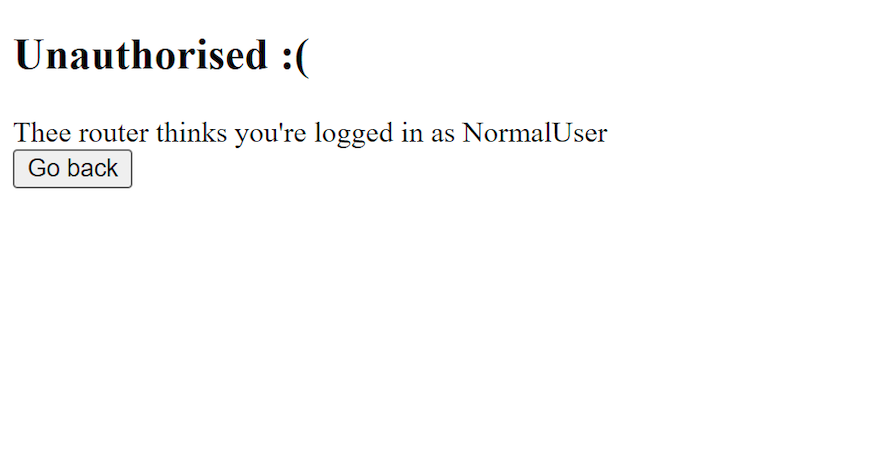

Then, we can make the changes to our unauthorized page:

<h2>Unauthorized :(</h2>

@if (this.loginDuringAuth() == undefined){

The router thinks you're not logged in.

} @else {

The router thinks you're logged in as {{LoginType[this.loginDuringAuth()!]}}

}

<br>

<button (click)="goBack()">Go back</button>

Now, we pass through the router state and display the result on the screen:

Having RedirectCommand provides a favorable outcome because all existing routing operations will still work and more complex routing operations are possible.

@let operatorThe other notable addition to Angular 18 — specifically, the incremental v18.1 release — is the @let operator. As Angular developers, we’re likely already familiar with the let operator in TypeScript, along with var, const, etc. But now it’s in the template code, so what gives?

Essentially, @let lets us define and assign variables within the template itself. If that sounds scary to you, that’s totally understandable. It’s not so hard to imagine how people would completely misuse this and declare way-too-complex business logic in their views. In the long run, that’s going to hurt debugging and troubleshooting.

Still, @let is a good addition because it means that we can easily access asynchronous variables with the async pipe without worrying about being personally responsible for unsubscribing. How would our unauthorized page change if we used @let?.

Instead of using @if statements, we can update our code like this:

<h2>Unauthorized :(</h2>

@let authStatus = this.loginDuringAuth() ?? 'Not logged in';

The router thinks you're logged in as {{authStatus}}

<button (click)="goBack()">Go back</button>

That’s a pretty basic example, but if you have a single view and you just want to quickly declare a variable in the view, it becomes quite simple.

@let operator in AngularThere are many ways to use the @let keyword. But let’s pause for some real talk — as developers, we’ve all encountered code that is badly written or isn’t easy to follow. If you use @let to define all of your application logic in your views, and forego writing any more TypeScript, you’re likely to gain an unfavorable reputation.

Imagine the horror! You’ll notice that your co-workers stop talking when you enter the room. Nicknames like “Letty” will be assigned. Tales will be told about Letty, the developer who just used @let everywhere and created an un-debuggable mess.

Fabricated drama aside, if you find yourself starting to use @let to complete complicated business logic, or copy-and-pasting it over and over again in your code, stop. You’re on your way to creating an unintelligible mess and the people you work with will be upset with your life choices.

@let exists on in the view (or the template) to provide view-related functionality. So, use it for that — and don’t overuse it.

Using @let isn’t a magic bullet for performance either, and completing computationally intensive operations within a @let block will cause browser lockups and other bad things to happen. They should be completed within TypeScript — but you already knew that, right?

We’re definitely getting a lot of DX enhancements in Angular, and I for one am enjoying it immensely. These changes will continue to enhance Angular’s ease of use when developing your apps for the web.

Feel free to clone the project and see for yourself how these changes make a difference.

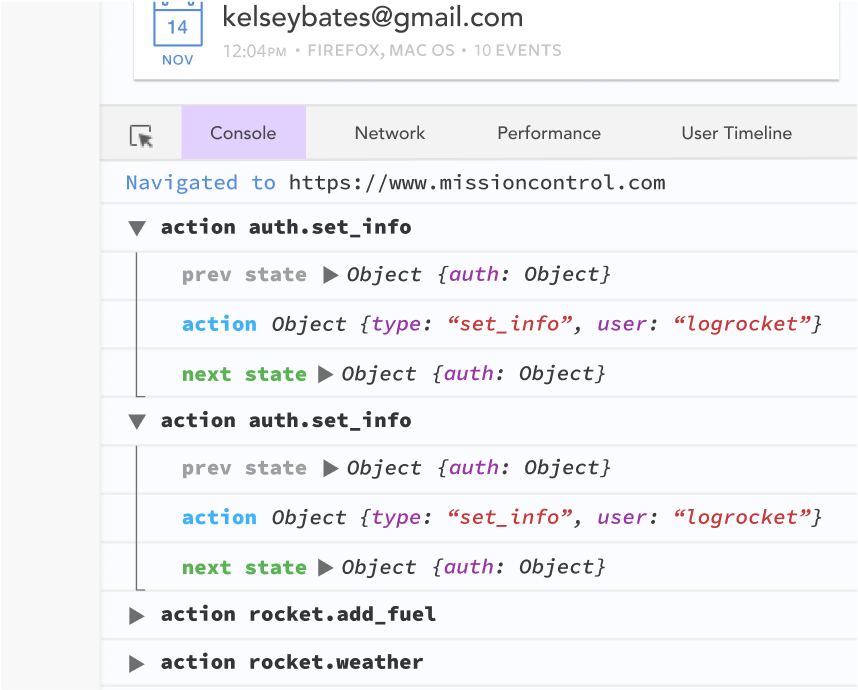

Debugging Angular applications can be difficult, especially when users experience issues that are difficult to reproduce. If you’re interested in monitoring and tracking Angular state and actions for all of your users in production, try LogRocket.

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings—compatible with all frameworks.

With Galileo AI, you can instantly identify and explain user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

The LogRocket NgRx plugin logs Angular state and actions to the LogRocket console, giving you context around what led to an error, and what state the application was in when an issue occurred.

Modernize how you debug your Angular apps — start monitoring for free.

Would you be interested in joining LogRocket's developer community?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

Not sure if low-code is right for your next project? This guide breaks down when to use it, when to avoid it, and how to make the right call.

Compare Firebase Studio, Lovable, and Replit for AI-powered app building. Find the best tool for your project needs.

Discover how to use Gemini CLI, Google’s new open-source AI agent that brings Gemini directly to your terminal.

This article explores several proven patterns for writing safer, cleaner, and more readable code in React and TypeScript.