Progressive web apps, or PWAs, are basically web apps that look and behave like native applications. While not as performant as native apps or apps built with device-specific frameworks like React Native, NW.js, etc., they can often be the solution for when you want to quickly create a cross-platform app from an existing web codebase.

In this tutorial, we’ll create a simple PWA built on React and Firebase. The app will display a list of ideas. We’ll be able to add and delete ideas to and from the list, and it will work offline as well. Instead of building a server for it, we’ll opt for a serverless architecture and let Firebase handle the heavy lifting for us.

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

Before we continue, I feel it’ll be a good idea to outline what this tutorial is and what it isn’t, just so we’re all on the same (web)page 🤭.

This tutorial assumes a couple of things:

What you’ll learn from this tutorial:

What you won’t learn from this tutorial:

We’ll build the app first, and when all the functionality is complete, we’ll then convert it into a PWA. This is just to structure the tutorial in a way that is easy to follow. Now that the expectations are set, it’s time to build!

You can find the source code for the finished version on my GitHub.

You can find the hosted version here.

Let’s talk a bit about the features and components of the app so we know what we’re getting ourselves into. The app is like a lightweight notes app where you record short ideas that you may have over the course of your day. You also have the ability to delete said ideas. You can’t edit them, though.

Another facet of the app is that it’s real-time. If we both open the app and I add or delete an idea on my end, you get the update at the same time so we both have the same list of ideas at any given time.

Now because we’re not implementing authentication, and because we’re sharing one single database, your ideas will not be unique to your app instance. If you add or delete an idea, everyone connected to the app will see your changes.

We’re also not going to create our own server to handle requests as you would in a traditional web application. Instead, the app is going to interface directly to a Firebase Firestore database. If you don’t know what Firestore is, just know that it’s a NoSQL database with real-time sync provided out of the box.

Welcome to serverless 😊.

So, to recap:

To get started, we’ll need to set up a new project on Firebase, get our credentials, and provision a Firestore database for it. Thankfully, this is a pretty straightforward process and shouldn’t take more than five minutes.

If you have experience with Firebase, go ahead and create a new project, create a web app, and provision a Firestore database for it. Otherwise, create a Firebase account, log in to your console, and follow the steps in this video below to get set up.

Setup Firebase + Firestore Web App

This is a setup video for the Lists PWA article on the LogRocket Blog.

Remember to copy your config details at the end of the process and save it somewhere for easy access. We’ll need it later on.

Now that we’re done creating the Firebase project, let’s set up our project locally. I’ll be using Parcel to bundle the app because it requires no setup whatsoever, and we don’t need advanced functionality.

Open your terminal (or command prompt for Windows) and run the following commands:

$ mkdir lists-pwa && cd lists-pwa $ npm init -y $ npm i -S firebase react react-dom $ npm i -D parcel parcel-bundler $ npm install -g firebase-tools $ mkdir src

Now, still in the same directory, run firebase login and sign in to your Firebase account. Now complete the following steps:

firebase initConfigure as a single-page app (rewrite all urls to /index.html)?. Type y and hit enterSome files will be automatically generated for you. Open firebase.json and replace the contents with the following:

{

"firestore": {

"rules": "firestore.rules",

"indexes": "firestore.indexes.json"

},

"hosting": {

"headers": [

{

"source": "/serviceWorker.js",

"headers": [

{

"key": "Cache-Control",

"value": "no-cache"

}

]

}

],

"public": "build",

"ignore": ["firebase.json", "**/.*", "**/node_modules/**"],

"rewrites": [

{

"source": "**",

"destination": "/index.html"

}

]

}

}

This will save you a lot of headaches later when trying to deploy the app to Firebase. Open the generated package.json, and replace the scripts section with the following:

"scripts": {

"start": "parcel public/index.html",

"build": "parcel build public/index.html --out-dir build --no-source-maps",

"deploy": "npm run build && firebase deploy"

},

If you don’t have experience with the React Context API, here’s a great tutorial that explains it in detail. It simply allows us to pass data from a parent component down to a child component without using props. This becomes very useful when working with children nested in multiple layers.

Inside the src folder, create another folder called firebase and create the following files:

config.jsindex.jswithFirebase.jsxOpen config.js and paste in the Firebase config file you copied earlier when setting up the Firebase project, but add an export keyword before it:

export const firebaseConfig = {

apiKey: REPLACE_WITH_YOURS,

authDomain: REPLACE_WITH_YOURS,

databaseURL: REPLACE_WITH_YOURS,

projectId: REPLACE_WITH_YOURS,

storageBucket: REPLACE_WITH_YOURS,

messagingSenderId: REPLACE_WITH_YOURS,

appId: REPLACE_WITH_YOURS

}

This config file is required when initializing Firebase.

Note: We’re not creating security rules for our Firestore database, which means anyone using this app will have read/write access to your project. You definitely don’t want this so please, look into security rules and protect your app accordingly.

Open index.js and paste in the following:

import { createContext } from 'react'

import FirebaseApp from 'firebase/app'

import 'firebase/firestore'

import { firebaseConfig } from './config'

class Firebase {

constructor() {

if (!FirebaseApp.apps.length) {

FirebaseApp.initializeApp(firebaseConfig)

FirebaseApp.firestore()

.enablePersistence({ synchronizeTabs: true })

.catch(err => console.log(err))

}

// instance variables

this.db = FirebaseApp.firestore()

this.ideasCollection = this.db.collection('ideas')

}

}

const FirebaseContext = createContext(null)

export { Firebase, FirebaseContext, FirebaseApp }

This is a pretty straightforward file. We’re creating a class Firebase, which is going to hold our Firebase instance.

Inside the constructor, we first check if there are any Firebase instances currently running. If not, we initialize Firebase using the config we just created, then we enable persistence on the Firestore instance. This allows our database to be available even when offline, and when your app comes online, the data is synced with the live database.

We then create two instance variables: db and ideasCollection. This will allow us to interact with the database from within our React components.

We then create a new context with an initial value of null and assign that to a variable called FirebaseContext. Then, at the end of the file, we export { Firebase, FirebaseContext, FirebaseApp }.

Open withFirebase.jsx and paste in the following:

import React from 'react'

import { FirebaseContext } from '.'

export const withFirebase = Component => props => (

<FirebaseContext.Consumer>

{firebase => <Component {...props} firebase={firebase} />}

</FirebaseContext.Consumer>

)

This is a higher-order component that will provide the Firebase instance we created above to any component that is passed as an argument to it. This is just for convenience purposes, though, so you don’t need to use it, but I recommend you do to make your code easier to reason about.

Okay, we are done with everything related to Firebase now. Let’s code our components and get something on the screen already!

Note: To keep this tutorial focused on the main topics (React, Firebase, PWA), I’m not going to include the CSS for the styling. You can get that from the repo here.

Create a new folder inside src called components. Inside this folder, we’ll have just two components: App.jsx and Idea.jsx.

The App component is going to do the heavy lifting here as it’ll be responsible for actually interacting with the database to fetch the list of ideas, add new ideas, and delete existing ideas.

The Idea component is a dumb component that just displays a single idea. Before we start writing the code for these components, though, we have to do some things first.

Open public/index.html and replace the contents with the following:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1" />

<title>Lists PWA</title>

</head>

<body>

<noscript>You need to enable JavaScript to run this app.</noscript>

<div id="root"></div>

<script src="../src/index.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

Under the src folder, create a new file index.js, open it, and paste in the following:

import React from 'react'

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom'

import App from './components/App'

import { FirebaseContext, Firebase } from './firebase'

const rootNode = document.querySelector('#root')

ReactDOM.render(

<FirebaseContext.Provider value={new Firebase()}>

<App />

</FirebaseContext.Provider>,

rootNode

)

We are simply wrapping our App component with the Firebase Context we created earlier, giving a value of an instance of the Firebase class we defined, and rendering to the DOM. This will give all the components in our app access to the Firebase instance so that they can interact with the database directly thanks to our HOC, which we’ll see shortly.

Now let’s code our components. We’ll start with Idea.jsx because it’s simpler and has less moving parts.

Idea.jsximport React from 'react'

import './Idea.less'

const Idea = ({ idea, onDelete }) => (

<div className="app__content__idea">

<p className="app__content__idea__text">{idea.content}</p>

<button

type="button"

className="app__btn app__content__idea__btn"

id={idea.id}

onClick={onDelete}

>

–

</button>

</div>

)

export default Idea

This is a pretty simple component. All it does is return a div with some content received from its props — nothing to see here. You can get the code for Idea.less from here.

Note: If you’re using my Less styles, create a new file under src called variables.less and get the contents from here. Otherwise, things may not look right.

Let’s move on to something more exciting.

App.jsxThis is a much larger component so we’ll break it down bit by bit.

PS, you can get the code for App.less from here.

import React, { useState, useEffect, useRef } from 'react'

import Idea from './Idea'

import { withFirebase } from '../firebase/withFirebase'

import './App.less'

const App = props => {

const { ideasCollection } = props.firebase

const ideasContainer = useRef(null)

const [idea, setIdeaInput] = useState('')

const [ideas, setIdeas] = useState([])

useEffect(() => {

const unsubscribe = ideasCollection

.orderBy('timestamp', 'desc')

.onSnapshot(({ docs }) => {

const ideasFromDB = []

docs.forEach(doc => {

const details = {

id: doc.id,

content: doc.data().idea,

timestamp: doc.data().timestamp

}

ideasFromDB.push(details)

})

setIdeas(ideasFromDB)

})

return () => unsubscribe()

}, [])

...to be continued below...

OK, so let’s go through this. Right off the bat, we’re retrieving the ideasCollection instance variable from the Firebase instance we’re getting from the withFirebase HOC (we wrap the component at the end of the file).

Then we create a new ref to the section HTML element, which will hold the list of ideas coming in from the database (why we do this will become clear in a moment). We also create two state variables, idea to hold the value of a controlled HTML input element, and ideas to hold the list of ideas from the database.

We then create a useEffect Hook where most of the magic happens. Inside this Hook, we reference the collection of documents in the ideasCollection, order the documents inside by timestamp in descending order, and attach an onSnapShot event listener to it.

This listener listens for changes (create, update, delete) on the collection and gets called with updated data each time it detects a change.

We initialize a new empty array, ideasFromDB, and for each document (i.e., idea) coming from the database, we create a details object to hold its information and push the object to ideasFromDB.

When we’re done iterating over all the ideas, we then update the ideas state variable with ideasFromDB. Then, at the end of the useEffect call, we unsubscribe from listening to the database by calling the function unsubscribe to avoid memory leaks.

...continuation...

const onIdeaDelete = event => {

const { id } = event.target

ideasCollection.doc(id).delete()

}

const onIdeaAdd = event => {

event.preventDefault()

if (!idea.trim().length) return

setIdeaInput('')

ideasContainer.current.scrollTop = 0 // scroll to top of container

ideasCollection.add({

idea,

timestamp: new Date()

})

}

const renderIdeas = () => {

if (!ideas.length)

return <h2 className="app__content__no-idea">Add a new Idea...</h2>

return ideas.map(idea => (

<Idea key={idea.id} idea={idea} onDelete={onIdeaDelete} />

))

}

...to be continued below...

The next bit of code is a bit easier. Let’s go through them function by function.

onIdeaDeleteThis function handles deleting an idea. It’s a callback function passed to the onClick handler attached to the delete button on every idea being rendered to the DOM. It’s also pretty simple.

All the delete buttons on each idea have a unique ID, which is also the unique ID of the idea in the Firestore database. So when the button is clicked, we get this ID from the event.target object, target the document with that ID in the ideasCollection collection, and call a delete method on it.

This will remove the idea from the collection of ideas in the database, and since we’re listening to changes on this collection in our useEffect call, this will result in the onSnapShot listener getting triggered. This, in turn, updates our state with the new list of ideas minus the one we just deleted 🤯.

Isn’t Firebase just awesome?

onIdeaAddThis function does the exact opposite of the onIdeaDelete function. It’s a callback function passed to the onSubmit handler attached to the form containing the input where you add new ideas.

Firstly, we prevent the default behavior of the form submission and check if the input is empty. If it is, end the execution there; otherwise, continue. We then clear the input value to allow for new ideas to be added.

Remember the ref to the HTML section element we initialized in our setup? Well, this is why we need it. In cases where there are too many ideas to fit on the screen at once, we might scroll down to view the older ones.

When in this scrolled position, if we add a new idea, we want to scroll to the top of the container to view the latest idea, and so we set the scrollTop of the section element holding the ideas to 0. This has the effect of scrolling to the top of the HTML section element.

Finally, we reference the collection of ideas in the database, ideasCollection, and call the add method on it. We pass it an object containing the value from the input element and a timestamp of the current date.

This will again trigger our onSnapShot listener to update our list of ideas so that the ideas state variable gets updated to contain the latest idea we just added.

renderIdeasThis function does exactly what it says on the tin. It is responsible for rendering all the ideas to the DOM.

We check if we have any ideas to render at all. If not, we return an h2 element with the text: “Add a new Idea…” Otherwise, we map over the array of ideas, and for each idea, return the dumb Idea component we created earlier, passing it the required props.

Nothing to see here.

...continuation...

return (

<div className="app">

<header className="app__header">

<h1 className="app__header__h1">Idea Box</h1>

</header>

<section ref={ideasContainer} className="app__content">

{renderIdeas()}

</section>

<form className="app__footer" onSubmit={onIdeaAdd}>

<input

type="text"

className="app__footer__input"

placeholder="Add a new idea"

value={idea}

onChange={e => setIdeaInput(e.target.value)}

/>

<button type="submit" className="app__btn app__footer__submit-btn">

+

</button>

</form>

</div>

)

}

export default withFirebase(App)

The last bit of code here is the return statement that returns the JSX.

At the end of the file, we have a default export exporting the App component wrapped with the withFirebase HOC. This is what injects firebase as a prop to the component.

Assuming you copied the corresponding .less files for both components from my GitHub repo, you now have a fully functional application. In your terminal, run npm start and open http://localhost:1234 from your browser.

You should see your application running live. Add an idea. Delete it. Open another browser window and add an idea from there. Notice how the two windows are being synced automatically? That’s Firebase doing its job flawlessly 🔥.

I went ahead and added a theme switcher to mine, because why not? If you’d like to do the same, clone the repo from here.

You can deploy your app to Firebase by running npm run deploy.

If you’ve followed this tutorial up to this point, you’re a rockstar ⭐ and you deserve a gold medal. We’ve done most of the hard work creating the actual app, and all that’s left now is to convert it to a PWA and make it work offline.

But to do this, we need to understand two key components of PWAs:

Don’t be fooled by how impressive the name “web app manifest” sounds. It’s a rather simple concept, and I’ll just let Google explain it for you:

“The web app manifest is a simple JSON file that tells the browser about your web application and how it should behave when ‘installed’ on the user’s mobile device or desktop. Having a manifest is required by Chrome to show the Add to Home Screen prompt.

A typical manifest file includes information about the app

name,iconsit should use, thestart_urlit should start at when launched, and more.”

When we create a manifest file, we link to it from the head of our index.html file so that the browser can pick it up and work with it. These are some of the most important properties of your app that you can configure with a manifest file:

name: This is the name used on the app install promptshort_name: This is the name used on your user’s home screen, launcher, and places where space is limited. It is optionalicons: This is an array of image objects that represents icons to be used in places like the home screen, splash screen, etc. Each object is usually a reference to a different size of the same icon for different screen resolutionsstart_url : This tells your browser what URL your application should default to when installeddisplay: This tells your browser whether your app should look like a native app, a browser app, or a full-screenYou can find the full list of configurable properties here.

Service workers are more complex but very powerful. They are what makes offline web experiences possible, in addition to other functionality like push notifications, background syncs, etc. But what exactly are they?

Put simply, a service worker is a JavaScript script (we need a new name for JS 🤦) that runs in the background and is separate from a webpage. Service workers are a bit complex, so we’ll not go through everything here. Instead, you can read more about them on the Google Developers site, and when you’re done, you can come back here to get a practical experience with them.

I’m assuming you actually visited the Google Developers link above because we’re going to be using some concepts that you might not be familiar with. If this is your first time working with service workers, please, if you didn’t read it, now is the time to do so.

Ready? Can we move on now? Great.

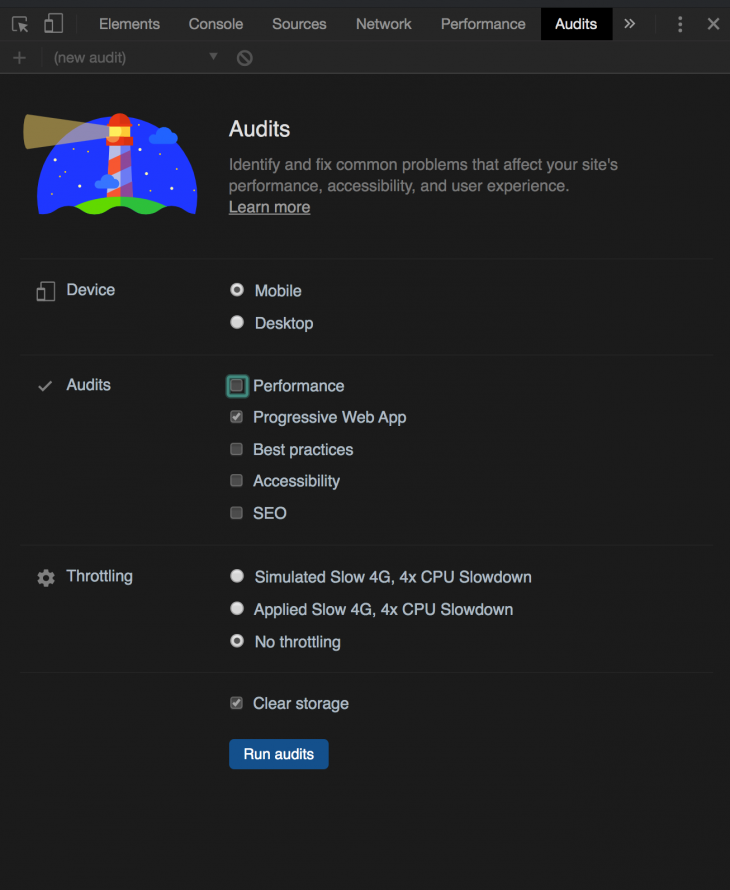

To make the process of developing a PWA as easy and seamless as possible, we’re going to be using a tool called Lighthouse to audit our app so we know exactly what we need to do to create a fully functional PWA.

If you already use the Chrome browser, then you already have Lighthouse installed in your browser. Otherwise, you may need to install Chrome to follow along.

npm startCOMMAND + OPTION + J for Mac and CTRL + SHIFT + J for Windows

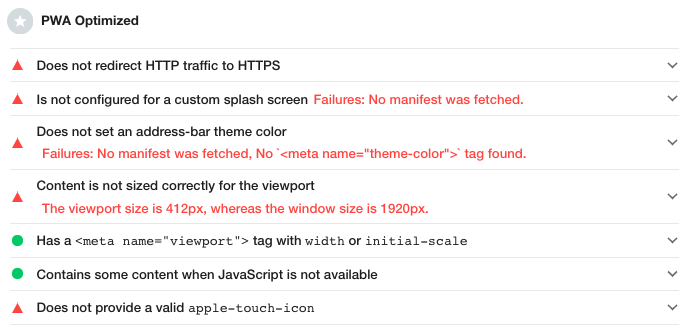

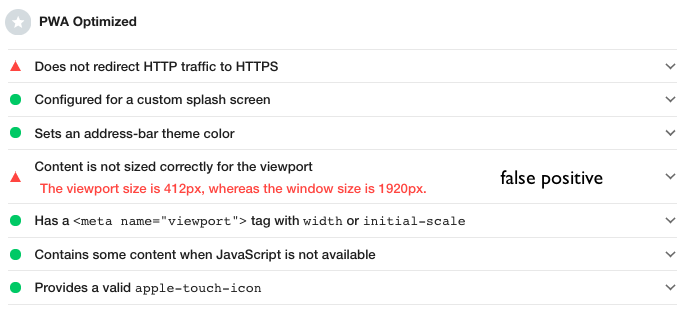

You should get a horrible result, but that’s to be expected because we’ve not done anything to make this app a PWA. Pay attention to the PWA Optimized section because that’s what we’ll be fixing first.

Let’s start, shall we?

Let’s start with the web app manifest file. This is usually a manifest.json file that is linked to in the index.html file, but because of the way Parcel works, we won’t be using a .json extension. Rather, we’ll use a .webmanifest extension, but the contents will remain exactly the same.

Inside the public folder, create a new file called manifest.webmanifest and paste the following content inside:

{

"name": "Lists PWA",

"short_name": "Idea!",

"icons": [

{

"src": "./icons/icon-128x128.png",

"type": "image/png",

"sizes": "128x128"

},

{

"src": "./icons/icon-256x256.png",

"type": "image/png",

"sizes": "256x256"

},

{

"src": "./icons/icon-512x512.png",

"type": "image/png",

"sizes": "512x512"

}

],

"start_url": ".",

"display": "standalone",

"background_color": "#333",

"theme_color": "#39c16c",

"orientation": "portrait"

}

Notice that in the "icons" section, we are linking to .png files under a /icons folder. You can get these images from the GitHub repo here, or you could choose to use custom images. Every other thing should be self-explanatory.

Now let’s make some changes to the index.html file. Open the file and add the following to the <head> section:

<link rel="shortcut icon" href="icons/icon-128x128.png" /> <link rel="manifest" href="manifest.webmanifest" /> <link rel="apple-touch-icon" href="icons/icon-512x512.png" /> <meta name="apple-mobile-web-app-capable" content="yes" /> <meta name="apple-mobile-web-app-status-bar-style" content="black" /> <meta name="apple-mobile-web-app-title" content="Lists PWA" /> <meta name="theme-color" content="#39c16c" /> <meta name="description" content="Lists PWA with React" />

Here’s what is going on:

apple)OK, now kill your running app, start it again, and let’s run the Lighthouse audit again and see what we get now.

Notice that we now get an almost perfect score under the PWA Optimized section. The Does not redirect HTTP traffic to HTTPS cannot be fixed in localhost mode. If you run the test on the app when hosted on Firebase, this should pass, too.

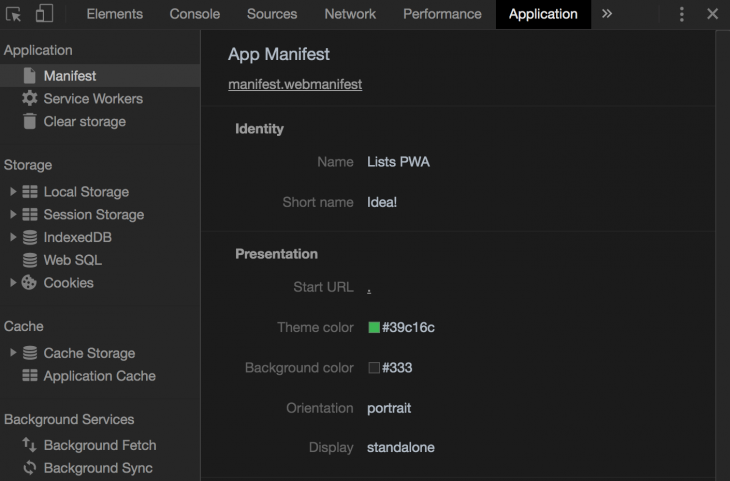

Still in the browser console, tab over to the Application tab and click on Manifest under the Application section. You should see details from the manifest.webmanifest file here, like so:

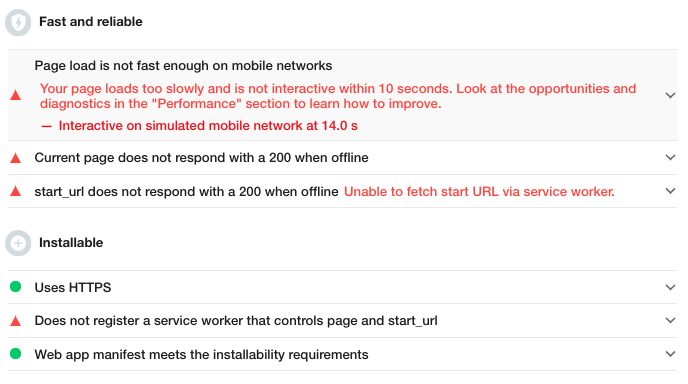

We’ve confirmed that our manifest file is working correctly, so let’s fix these other issues on the Lighthouse PWA audit:

start_url does not respond with a 200 when offlineTo fix the issues listed above, we need to add a service worker (I’ll be abbreviating it to SW from now on to keep my sanity) to the application. After registering the SW, we’re going to cache all the files we need to be able to serve them offline.

Note: To make things easier, I recommend opening your app in an incognito tab for the rest of this tutorial. This is due to the nature of the SW lifecycles. (Did you visit that link like I asked?)

Under the public folder, create a new file called serviceWorker.js and paste in the following for now: console.log('service worker registered').

Now open the index.html file and add a new script:

<script>

if ('serviceWorker' in navigator) {

window.addEventListener('load', () => {

navigator.serviceWorker.register('serviceWorker.js');

});

}

</script>

Let’s dissect this script. We’re checking if the current browser supports SWs (SW support), and if it does, we add a 'load' event listener to the window object.

Once the window is loaded, we tell the browser to register the SW file at the location serviceWorker.js. You can place your SW file anywhere, but I like to keep it in the public folder.

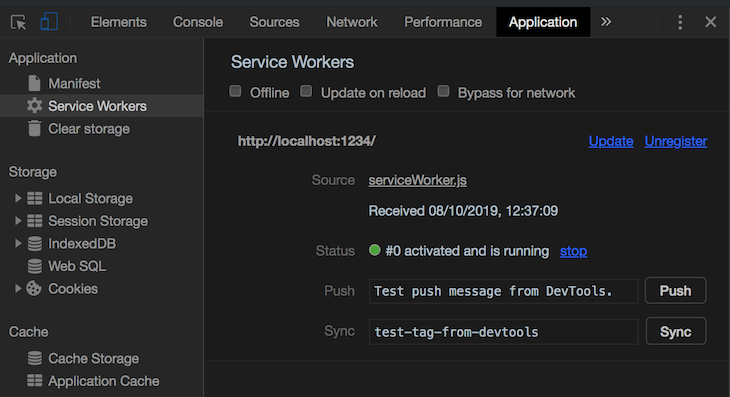

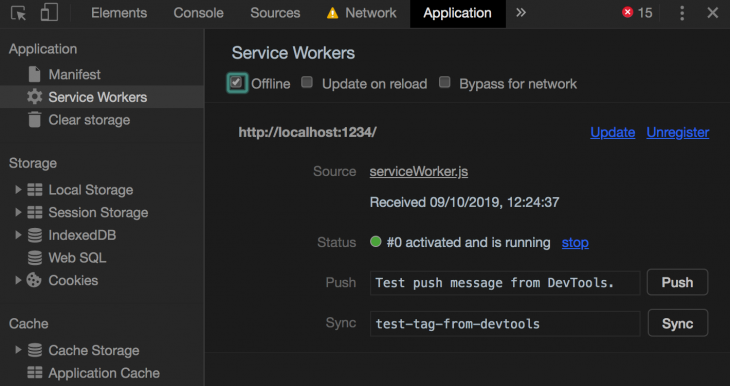

Save your changes, restart your app in incognito mode, and open the console. You should see the message service worker registered logged. Great. Now open the Application tab in the DevTools and click on Service Workers. You should see our new SW running.

Right now, our SW is running, but it’s a bit useless. Let’s add some functionality to it.

So this is what we need to do:

Open the serviceWorker.js file and replace the contents with the following:

const version = 'v1/';

const assetsToCache = [

'/',

'/src.7ed060e2.js',

'/src.7ed060e2.css',

'/manifest.webmanifest',

'/icon-128x128.3915c9ec.png',

'/icon-256x256.3b420b72.png',

'/icon-512x512.fd0e04dd.png',

];

self.addEventListener('install', (event) => {

self.skipWaiting();

event.waitUntil(

caches

.open(version + 'assetsToCache')

.then((cache) => cache.addAll(assetsToCache))

.then(() => console.log('assets cached')),

);

});

What’s going on here? Well, at the beginning, we’re defining two variables:

version: Useful for keeping track of your SW versionassetsToCache: The list of files we want to cache. These files are required for our application to work properlyNote: The following section only applies if you use Parcel to bundle your application.

Now, notice that the filenames in the assetsToCache array have a random eight-letter string added before the file extensions?

When Parcel bundles our app, it adds a unique hash generated from the contents of the files to the filenames, and this means the hashes will most likely be unique every time we make changes to the contents of the files. The implication of this is that we have to update this array every time we make a change to any of these files.

Thankfully, we can solve this pretty easily by telling Parcel to generate the hash based on the location of the files instead of the contents. That way, we are guaranteed that the hash will be constant, provided we don’t change the location of any file.

While we still have to update the array whenever we change their locations, this won’t happen as frequently as it would if we stuck with the default hashing scheme.

So how do we tell Parcel to use the location? Simply open your package.json and add --no-content-hash to the end of the build script. This is important.

After initializing those variables, we then add an event listener to a self object, which refers to the SW itself.

We want to perform certain actions when the SW starts running, so we specify which event we’re listening for, which, in our case, is the install event. We then provide a callback function that takes in an event object as a parameter.

Inside this callback, we call skipWaiting() on the SW, which basically forces the activation of the current SW. Please read about the lifecycles of service workers to understand why this step is here. I’m not sure I can do a better job of explaining it than the Google Developers site.

We then call a waitUntil() method on the event object passed to the callback, which effectively prevents the SW from moving on to the next stage in its lifecycle until whatever argument we pass to it is resolved. Let’s look at this argument in a bit more detail.

We are making use of the Cache API, so I suggest you brush up on that before continuing. We open a cache storage called v1/assetsToCache (it’ll be created if it didn’t previously exist), which returns a promise.

We then chain a .then method on the result and pass in a callback that takes in a parameter called cache, which is an instance of the cache storage we just opened. Then, we call the addAll() method on this instance, passing in the list of files we wish to cache. When we’re done, we log assets cached to the console.

Let’s recap what we’ve done so far:

Paste the following code after the previous one:

self.addEventListener('fetch', (event) => {

if (event.request.method === 'GET') {

event.respondWith(

fetch(event.request).catch(() => {

return caches.match(event.request);

}),

);

}

});

We want to serve up the cached files whenever the user’s network is down so that they don’t get the infamous Chrome T-Rex.

So we’re going to add another event listener for all network fetch requests and check if it is a GET request (i.e., is the browser asking for resources?). If it is, we will try to get the resource from the server, and if that fails, serve up the cached resource. How are we doing this?

In the callback passed to the event listener, we’re checking if event.request.method is equal to GET. If it isn’t (e.g., a user is adding a new idea), then we’re not going to handle the request. Remember that we enabled persistence in our Firestore instance during the setup, so Firestore is going to handle that scenario for us. All we’re interested in is handling GET requests.

So if it’s a GET request, we’re going to try and query the server using the Fetch API for the requested data. This will fail if the user is offline, so we’ve attached a catch method to the result of that request.

Inside this catch block, we return whichever cached file matches the requested resource from the Cache storage. This ensures that the app never knows that the network is down because it is receiving a response to the request.

We’ve done everything we need to make the app a fully functional PWA with offline connectivity, so let’s test it.

Kill your app (if it was running) and start it again. Open the Chrome DevTools, tab over to the Application tab, click on Service Workers, and you should see our SW activated and running like a 1968 Corvette on the Autobahn. Great.

Now check the Offline checkbox and reload the page like so:

Notice that your app didn’t even flinch. It kept running like all was well with the world. You can switch off your WiFi and try reloading the page again. Notice it still comes up fine.

Now let’s deploy the app to Firebase, install it as a PWA on an actual mobile device, and confirm that everything works.

Run npm run deploy and visit the hosting URL provided to you by Firebase on a mobile device. You should get a prompt to install the application. Install it, visit your app launcher menu, and you should see “Idea!” (or whatever name you decided on) amongst the list of native apps.

Launch it and the app should load up like a native app complete with a splash screen. If someone were to walk in on you using the app right now, they would be unable to tell that it is not a native mobile application.

This tutorial was a long one, but we’ve only scratched the surface of what we can accomplish with React + Firebase + PWAs. Think of this tutorial like a gentle intro into the amazing world of building progressive web applications.

While you could certainly work with the Service Worker API directly, there are a lot of things that could go wrong, so it is much more advisable to use Google’s Workbox instead. It takes care of a lot of the heavy lifting and frees you to concentrate on the features that really matter. For instance, if you check the version on the repo, you’ll find that that is exactly what I’m using.

I hope you enjoyed this tutorial and happy coding ❤️!

Install LogRocket via npm or script tag. LogRocket.init() must be called client-side, not

server-side

$ npm i --save logrocket

// Code:

import LogRocket from 'logrocket';

LogRocket.init('app/id');

// Add to your HTML:

<script src="https://cdn.lr-ingest.com/LogRocket.min.js"></script>

<script>window.LogRocket && window.LogRocket.init('app/id');</script>

If your AI app or agent works perfectly in development but falls apart in production, you’re not alone. In a […]

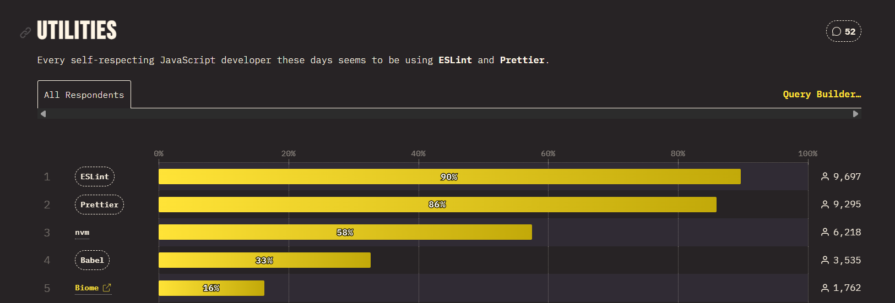

Compare ESLint and Oxlint, benchmark real speed gains, and learn when migrating to Oxlint makes sense for modern JavaScript teams.

Discover five practical ways to scale knowledge sharing across engineering teams and reduce onboarding time, bottlenecks, and lost context.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the March 4th issue.

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now