Today’s browsers can handle most of the problems that frontend frameworks were originally created to solve. Web Components provide encapsulation, ES modules manage dependencies, modern CSS features like Grid and container queries enable complex layouts, and the Fetch API covers network requests.

Despite this, developers still default to React, Angular, Vue, or another JavaScript framework to address problems the browser already handles natively. That default often trades real user costs –page weight, performance, and SEO – for developer convenience.

In this article, we’ll explore when frameworks are genuinely necessary, when native web APIs are enough, and how often we actually need a framework at all today.

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

“Frameworkism” and “anti-frameworkism” aren’t formal terms or established movements. They’re shorthand for two competing defaults in how developers approach new projects. At its core, the divide is about where you choose to start.

Frameworkism follows a framework-first mindset. A framework – most often React – is selected upfront and treated as the baseline. This approach assumes fast devices and reliable networks, starts heavy by default, and relies on optimization later if performance issues show up.

Anti-frameworkism takes the opposite approach. It starts with zero dependencies and adds only what’s necessary. Frameworks are tools for specific problems, not the default solution. Developers lean on native browser capabilities first and introduce frameworks only when they hit real limitations. This mindset makes fewer assumptions about user conditions, accounting for slower devices and imperfect networks from the start.

Cross-browser compatibility is largely a solved problem today. Internet Explorer is no longer in the picture, and even Safari supports most modern web APIs, with only a few caveats. Many of the platform gaps that originally drove the adoption of frameworks like React have since been closed.

The web platform has evolved significantly over the past few years. For a large number of everyday use cases, vanilla JavaScript is more than sufficient.

Below are some of the most important capabilities the platform provides.

Web Components are built on three core technologies:

Together, these APIs provide a component-based architecture without relying on a framework. Below is a simple example of a Web Component (and here are some more advanced ones):

class TodoItem extends HTMLElement {

constructor() {

super();

this.attachShadow({ mode: 'open' });

}

connectedCallback() {

this.shadowRoot.innerHTML = `

<style>

:host { display: block; padding: 10px; }

.completed { text-decoration: line-through; }

</style>

<div class="${this.hasAttribute('completed') ? 'completed' : ''}">

<slot></slot>

</div>

`;

}

}

customElements.define('todo-item', TodoItem);

The component above has encapsulated styles and lifecycle methods (constructor() creates the shadow root, while connectedCallback() runs when the element is added to the DOM).

You can add it to your HTML page like a regular HTML tag:

<!-- Basic usage --> <todo-item>Learn Web Components</todo-item> <!-- With 'completed' state --> <todo-item completed>Pick UX over DX</todo-item>

There’s no transpilation step (such as converting JSX to JavaScript), no virtual DOM abstraction, and no required build step—though you can still use build tools if you want. The code runs directly in the browser and starts instantly because there’s no framework to initialize.

On the other hand, Web Components don’t provide built-in reactivity. Unlike frameworks such as React, where you describe the UI and the framework automatically handles updates, Web Components are imperative. You need to manage DOM updates and respond to attribute or state changes manually, unless you introduce a library like Lit.

Self-contained leaf components – such as emoji pickers, date selectors, and color pickers—work particularly well as Web Components. They live at the edges of the component tree and don’t contain nested children. Because of that, they avoid much of the complexity around server-side rendering and passing content across multiple shadow DOM boundaries.

Native approaches shine when dealing with mostly static content that needs a small amount of interactivity. Most websites are still just HTML documents with occasional dynamic behavior, which can be added through progressive enhancementusing vanilla JavaScript.

For example, here’s how you might enhance a basic contact form with asynchronous submission using the Fetch API:

document.querySelector('form').addEventListener('submit', async (e) => {

e.preventDefault();

const formData = new FormData(e.target);

const response = await fetch('/api/submit', {

method: 'POST',

body: formData

});

if (response.ok) {

e.target.innerHTML = '<p>Thanks, your message has been sent!</p>';

}

});

Beyond Web Components and basic interactivity, the web platform now covers most of the responsibilities frameworks were originally designed to handle. Native ES modules and dynamic imports support dependency management and code splitting, import maps simplify working with third-party libraries, and the Fetch API handles network requests. On the styling side, modern CSS features such as animations, container queries, and custom properties make complex, responsive layouts possible without JavaScript-heavy abstractions.

Long-term maintenance tends to favor native approaches. Vanilla JavaScript, written a decade ago, still runs today, while framework-based applications often require substantial rewrites with each major release. Native web APIs don’t depend on external tooling or package ecosystems, and they maintain backward compatibility far more consistently. As a result, the knowledge you invest in the platform stays relevant for years, not just for a few release cycles.

Server-side rendering once depended heavily on frameworks, but the web platform has made significant progress here as well. Declarative Shadow DOM, now supported across all major browsers, lets you define shadow roots directly in HTML using the shadowrootmode attribute, without relying on JavaScript.

In the example below, the component renders immediately instead of waiting for JavaScript to execute, improving initial paint times. The CSS also responds to attributes – the completed state applies a strikethrough purely through the :host([completed]) selector.

<todo-item completed>

<template shadowrootmode="open">

<style>

:host { display: block; padding: 10px; }

:host([completed]) div { text-decoration: line-through; }

</style>

<div><slot></slot></div>

</template>

Pick UX over DX

</todo-item>

<script>

class TodoItem extends HTMLElement {

constructor() {

super(); // No attachShadow() needed!

}

}

customElements.define('todo-item', TodoItem);

</script>

AI coding tools reinforce the framework-first default by generating React and other popular framework-based solutions, often paired with tools like Tailwind. This isn’t because these are always the best choices, but because framework-heavy code dominates their training data. Paul Kinlan described this AI-driven effect as dead framework theory. While his claim that React has permanently won and alternatives are “dead on arrival” may be overly pessimistic, the core observation holds.

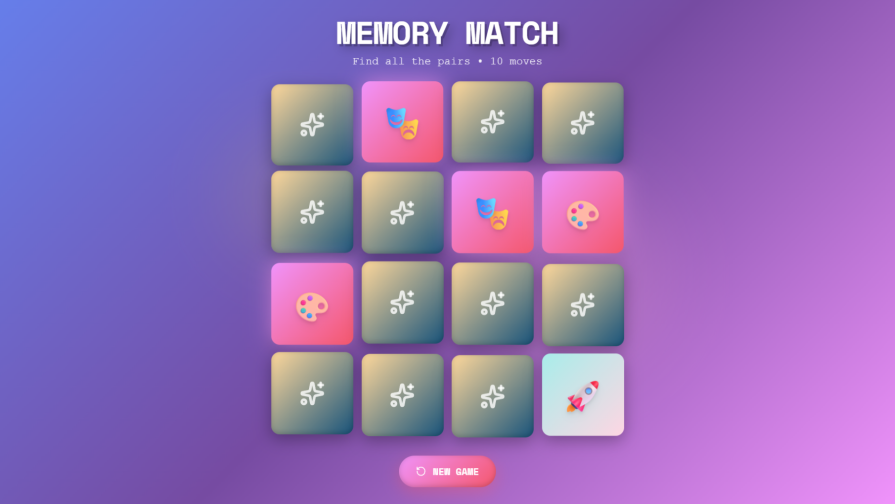

An experiment: what it reveals about vibe coding, output quality, and framework weight?

To see whether this theory shows up in practice, I ran a small experiment using Claude to generate a memory game. Different tools may behave differently, so this should be treated as a single data point rather than a universal result.

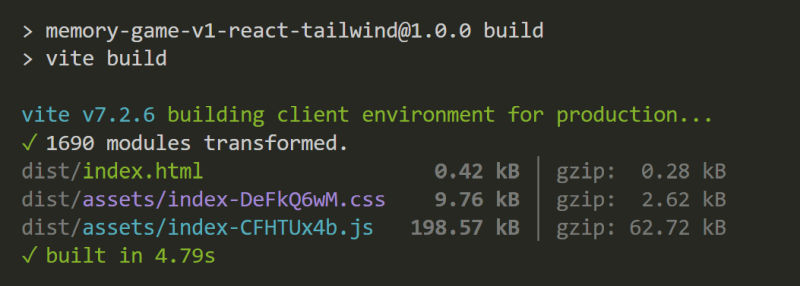

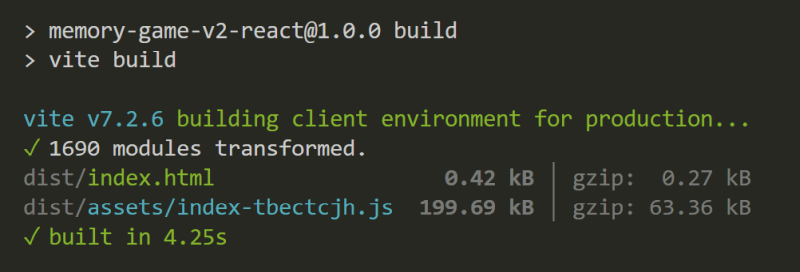

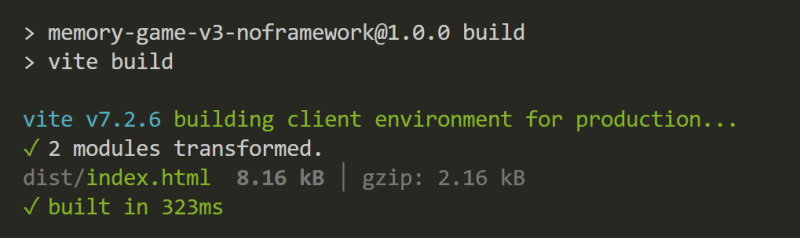

In the table below, you can see the key findings:

| V1 (React + Tailwind) | V2 (React) | V3 (No framework) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prompt | “Create a memory game” | “Create a simple memory game” | “Create a simple HTML memory game” |

| Prompt specificity | Low (minimal guidance) | Medium (no tech specified) | High (HTML specified) |

| Functionality | Card matching, flip animations, move counter, win detection, reset | Card matching, flip animations, move counter, win detection, reset | Card matching, flip animations, move counter, win detection, reset |

| Frameworks | React, ReactDOM, Tailwind CSS, lucide-react | React, ReactDOM, lucide-react | None |

| Fonts | Google Fonts (Space Mono) | Google Fonts (Fredoka) | System font (Arial) |

| Icons | lucide-react (UI icons: Sparkles, RotateCcw) + UTF-8 emoji for cards | lucide-react (8 card icons: Sparkles, Star, Heart, Zap, Sun, Moon, Cloud, Flame) | UTF-8 emoji (🎮🎯🎨🎭🎪🎸🎺🎻) |

| Core bundle (min + gzip) | 65.62 KB | 63.63 KB | 2.16 KB |

| Demo links | Demo v1 (React + Tailwind) |

Demo v2 (React) |

Demo v3 (No framework) |

| Screenshot of demo |  |

|

|

| Bundle size (VSCodium) |  |

|

|

As you can see above, the memory game functionality is identical across all versions, and the aesthetics are just slightly better in the framework-based versions, thanks to React Lucide (however, note that you can add Lucide icons as inline SVG without React). Yet v1 and v2 are both about 30× larger than the vanilla one, with 95% of the bundle being framework overhead. React and Tailwind didn’t make the output noticeably better; they just made it heavier.

This also demonstrates dead framework theory in action. Without specific guidance, AI defaults to React indeed. You can fight this by increasing prompt specificity, but since most people using AI tools won’t do that, this remains a huge win for frameworkism.

Frameworks introduce real performance overhead. In the memory game example above, the React versions are roughly 30× larger than the native JavaScript implementation.

In larger production applications, that overhead grows well beyond the initial ~60 KB as routing, state management, UI libraries, and other utilities are added. A typical React application with a full ecosystem can easily ship 150–300 KB of framework-related code.

Vanilla applications also grow in size as complexity increases, which makes proportional comparisons harder. Even so, frameworks add a fixed layer of overhead that exists regardless of application scale.

Lower page weight and faster load times are clear UX wins for an anti-frameworkist approach, but they come with trade-offs in developer experience. Writing Web Components by hand can be verbose. Passing props, handling events, and managing updates requires more manual work than in most frameworks, and state management across many components becomes difficult without established patterns.

This is where lighter alternatives can help bridge the gap between vanilla verbosity (a DX cost) and framework bloat (aUX cost):

These libraries improve developer experience compared to fully vanilla JavaScript while keeping bundle sizes in check. That said, users don’t care about your DX. They care that the site loads quickly on their device and connection, and that it does what they came for.

For small to medium applications, the DX benefits of heavyweight frameworks like React rarely justify the UX costs they introduce. They can still make sense for enterprise-scale, highly interactive dashboards built by large teams, but those cases represent a small minority of the websites and applications that use them today.

Web platform features work at scale. When Netflix replaced React with vanilla JavaScript on its landing page, load time and Time to Interactive dropped by more than 50 percent, and the JavaScript bundle shrank by roughly 200 KB. GitHubrelies heavily on custom Web Components through Catalyst, its open-source library for reducing boilerplate. Adobe moved Photoshop to the web using Lit-based Web Components. These aren’t edge cases – they show that the web platform is production-ready.

The job market, however, is messier. Resume-driven development is a well-documented reality, and React still dominates job listings. To stay employable, you’ll almost certainly need to learn React. But the job market reflects what companies already use, not what’s technically best for new projects. To become excellent – not just employable – you need to understand native web APIs and know when each approach makes sense.

Anti-frameworkism isn’t about rejecting tools. It’s about starting from the problem instead of the trend, weighing real-world impact before convenience, and choosing the technology that best serves your users.

Discover five practical ways to scale knowledge sharing across engineering teams and reduce onboarding time, bottlenecks, and lost context.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the March 4th issue.

Paige, Jack, Paul, and Noel dig into the biggest shifts reshaping web development right now, from OpenClaw’s foundation move to AI-powered browsers and the growing mental load of agent-driven workflows.

Check out alternatives to the Headless UI library to find unstyled components to optimize your website’s performance without compromising your design.

Would you be interested in joining LogRocket's developer community?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

One Reply to "Anti-frameworkism: Choosing native web APIs over frameworks"

The transitions API also makes the case for a ‘SPA’ less necessary as you can achieve a smoother client side UX without building an actual SPA.