Ever since the inception of the Android OS, the concept of intents has been one of the main building blocks for navigation within the operating system. As defined by Google, an Intent is an abstract description of an operation to be performed. It may also be looked at as a messaging object you can use to request an action from another app component, as the Android official documentation further explains, and intents are generally known to be used for three main use cases: starting an Activity, a Service, and to deliver messages to a BroadcastReceiver.

There are two main types of intents: explicit, and implicit intents. Without getting too much detail and the differences between the two, it is the latter type of intent that actively deals with intent filters, the main topic of this article.

Jump ahead:

Activity intents

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

Intent filters are defined by the Android documentation as “an expression in an app’s Manifest.xml file that specifies the type of intents that the component would like to receive.” As it was previously alluded to, intent filters only work when we’re working with implicit intents, as these kind of intents require the Android system to find the appropriate component to start by comparing the contents of the intent to the intent filters declared in the Manifest file of other applications on the device.

In this article, we will explore the nature of <intent-filter>, its relationship to the Android OS, as well as its usage inside the Manifest.xml file and the ecosystem. We will then go over some common examples of intent filters, as well as some more advanced ways of using them, with the goal of better understanding the role that these crucial pieces of information play in an Android application.

Intent filters are inexorably married to implicit intents, because these declare a general action to perform, as the Android documentation explains, which then allows a component from another application to handle it instead.

An easy example to think of is whenever we want to send an email, we invoke an implicit intent that email applications may then consume and help us achieve our end goal. It is because of this strong relationship between implicit intents and intent filters that from here on, every time we mention an intent in this article we will be explicitly talking about implicit intents, unless otherwise stated.

As previously suggested, intent filters are defined in code inside the Manifest.xml file. The Manifest is typically used for much of the main set up of any application, as it declares the application name, icon, the permissions it needs, etc. The Manifest is also responsible for declaring activities, services and broadcast receivers, and it is within these components that we define our intent filters.

The simplest example of an <intent-filter> can be found in the application’s main activity — or the activity that the user sees first — where we add an intent filter declaring it to be the main activity of the application, as well as the launching activity:

<activity

android:name="com.ivangarzab.examples.MainActivity"

android:exported="true">

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="android.intent.action.MAIN" />

<category android:name="android.intent.category.LAUNCHER" />

</intent-filter>

</activity>

It’s worth nothing in this example that the attribute of android:exported has to be explicitly set in all types of app components — i.e. activities, services, broadcast receivers — or otherwise the application will not be able to successfully install on devices running Android 12 or higher.

Speaking of attributes, intent filters have a small pool of attributes that may be set within them in order to specify the type of intents that this component accepts: action, data, and category. Here are the definitions of each one of these elements according to the Android developer guide:

<action> – Declares the intent action accepted, in the name attribute. The value must be the literal string value of an action, not the class constant<data> – Declares the type of data accepted, using one or more attributes that specify various aspects of the data URI (scheme, host, port, path) and MIME type<category> – Declares the intent category accepted in the name attribute. The value must be the literal string value of an action, not the class constantIf we look back at our first example above, we can see the most basic use of both <action> and <category> attributes, where the action to declare an Activity into the main activity reads android.intent.action.MAIN, and the category to declare that same activity the launching activity similarly reads android.intent.category.LAUNCHER.

Let’s jump into another example to further demonstrate how to use all of these different intent filter elements at the same time:

<activity android:name="com.ivangarzab.examples.SendActivity"

android:exported="false">

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="android.intent.action.SEND"/>

<category android:name="android.intent.category.DEFAULT"/>

<data android:mimeType="text/plain"/>

</intent-filter>

</activity>

For this second example, we’re declaring another Activity named SendActivity that contains a nested <intent-filter> declaring all three types of attributes inside of it. It has an action of type ACTION_SEND, a category of type DEFAULT, and a data element that contains the kind of data we want to send using the incoming intent, which reads text/plain.

Evidently, the kind of intent that is being consumed here is meant to deliver some data to someone else, as per its official documentation, and this type of intent is commonly declared by email applications, for example.

It should be noted that the only way for your activities to correctly receive implicit intents is for the CATEGORY_DEFAULT filter to be declared. Both functions startActivity() and startActivityForResult() declare that category by default when called, which means that the intent filter should expect that category from the receiving end as well.

Activity intentsSo far we’ve only seen how to declare intent filters in the Manifest file, which allows the application to receive intents. In contrast, sending intents is done directly in code, and requires a bit of setup in order to make sure we include all of the attributes and information needed to land and successfully communicate an intent to another application.

Conversely, the actual receiving and processing of incoming intents, i.e., intents that have been filtered by the Manifest and are being consumed by our application, requires a conditional block statement within their respective app components for handling as well.

Let’s start by showcasing how to set up and send an intent. In our last example with the ACTION_SEND intent, we briefly mentioned that this could be used to send information over to somebody else, like in an email.

The way you would set up an ACTION_SEND intent that would be correctly filtered by the code specified above, would require something like this:

fun composeEmail(data: EmailData) =

Intent(Intent.ACTION_SEND).apply {

type = "text/plain"

putExtra(Intent.EXTRA_EMAIL, data.addresses)

putExtra(Intent.EXTRA_SUBJECT, data.subject)

}.let { intent ->

if (intent.resolveActivity(packageManager) != null) {

startActivity(intent)

}

}

In this example, we have a function that creates an Intent object first, specifying the content type inside its type field, and then adding some extra fields that may be leveraged by the receiving end. After that, we make sure that there is an <activity> component that can be resolved to our specifications, and if so, we go ahead and call startActivity(intent) passing in the recently created intent, with the hopes of delivering our message to another application.

Similarly enough, sending a Service or BroadcastReceiver intent is not very different from sending an Activity intent, as they would simply call startService(intent) and sendBroadcast(intent), respectively. However, these alternative types of components may require a different kind of setup in order to be correctly filtered by other applications.

Differently but in parallel, app components need to be set up to handle incoming intents. This is usually done in the main override method of the component, like in the onCreate() of an Activity component.

Finishing off with the series of examples using the ACTION_SEND intent, the SendActivity class that we declared in the Manifest file two examples above would need to add the following block of code to its onCreate(..) method in order to be able to process the intent correctly:

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

...

intent?.let {

when (it.action) {

Intent.ACTION_SEND -> {

// All send intents land here

if (it.type == "text/plain") {

// Handle sending text

} else // Handle all other type of send intent actions

}

}

}

...

}

In this final example of the ACTION_SEND series, we’ve set up the onCreate() method of an Activity so that it is able to process the given kind of intent, and even added a further conditional statement discriminating ACTION_SEND intent by the type of data that they are holding.

Now that we have a better understanding of what intent filters are, how they relate to intents and how they are sent and received, let’s look at different types of intent filters, and some of their different uses for other Android components.

A common example of an implicit intent declaration in the Manifest could be showing a location on a map.

Map applications, as well as driving or food delivering apps, may expose their activities to the OS, allowing them to receive intents attempting to show a location in a map. The following code shows what kind of intent filters would be needed to achieve that goal:

<activity

android:name="com.ivangarzab.examples.MapActivity"

android:exported="false">

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="android.intent.action.VIEW" />

<category android:name="android.intent.category.DEFAULT" />

<data android:scheme="geo" />

</intent-filter>

</activity>

Another very common example that almost any application could implement is that of capturing a picture or video using the built-in camera. The following code shows how to set up the correct <intent-filter> to achieve the capturing of a picture or video, as well as returning it to the calling application:

<activity

android:name="com.ivangarzab.examples.CaptureActivity"

android:exported="false">

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="android.media.action.IMAGE_CAPTURE" />

<category android:name="android.intent.category.DEFAULT" />

</intent-filter>

</activity>

So far, most of the examples that we have gone through have been dealing with intent and intent filters with relation to Activity components. However, activities are not the only app components that can be started using intents.

Both services and broadcast receivers may also be started and handled using intents, and both of these component types also utilize intent filters in their Manifest declarations:

<service

android:name="com.ivangarzab.examples.AudioService"

android:exported="false">

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="android.media.browse.MediaBrowserService" />

</intent-filter>

</service>

<receiver

android:name="androidx.media.session.MediaButtonReceiver"

android:exported="false">

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="android.intent.action.MEDIA_BUTTON" />

</intent-filter>

</receiver>

In this example, we’re showing a common <service> and <receiver> setup for dealing with an audio playing service and its companion media notification. There’s obviously a lot of context that we’re ignoring, but it should be apparent what the similarities and differences are, with respect to our previous <activity> examples above.

Now that we’ve seen some common examples of typical intents and their intent filters, as well as intents that attempt to communicate with components other than activities like services and broadcast receivers, let’s take one last look at an example in which we’ll be demonstrating two advanced ways of using intent filters: implementing custom intent actions, and having multiple filters in the same component:

<activity

android:name="com.ivangarzab.examples.MainActivity"

android:exported="true">

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="android.intent.action.MAIN" />

<category android:name="android.intent.category.LAUNCHER" />

</intent-filter>

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="ivangarzab.examples.action.TODO" />

<category android:name="android.intent.category.DEFAULT" />

</intent-filter>

</activity>

As previously mentioned, the example above shows two advanced cases of intent filters. First, we’re taking the MainActivity from the from our very first example, and extending it by adding a secondary <intent-filter> that defines a custom action of type TODO. Having multiple intent filters in a single component allows the given component to process and handle different kinds of incoming intents.

As it may be apparent, this second intent filter’s action element is not something we’re deriving from the Android SDK. Instead, custom actions may be defined per app, and can be used to extend a piece of functionality to be triggered from outside the application.

For example, our application could have a to-do list feature that allows outside applications to send new to-do elements as part of an intent. Our application would have to not only define custom intent filter action inside our activity’s Manifest declaration, but also handle the arrival of such type of intents inside the given Activity class as well:

class MainActivity : AppCompatActivity() {

...

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

...

intent?.let {

when (it.action) {

"ivangarzab.examples.action.TODO" -> {

// Handle TODO custom action

}

}

}

...

}

...

}

This final code block should look very familiar, as the handling of a custom action is exactly the same as how we would handle almost any other kind of specific Intent. The main difference between the code above and our example in the section about receiving intents is that, instead of grabbing the intent action definition from a pre-defined class inside the Android SDK, we’re manually defining the full name of the intent action.

Lastly, an outside application would have to know the exact definition of the custom intent as well, namely ivangarzab.examples.action.TODO, in order to ask the OS to find a component whose intent filter accepts that kind of action:

// Outside application

fun createToDo(data: ToDoData) =

Intent("ivangarzab.examples.action.TODO").apply {

putExtra(KEY_TASK, data.task)

putExtra(KEY_DATE, data.date)

startActivity(this)

}

All in all, intents are a very broad concept that may appear in myriad topics across the Android platform. Intents have became so important for the Android OS that an entire paradigm of software architecture known as MVI Architecture was created and dedicated to intents, their functionality, and their advantages.

In this article we’ve merely scratched the surface of what intents can do, and by concentrating on the usage of implicit intents, we’ve neglected a whole other world when it comes to explicit intents. Furthermore, broadcast receivers and services have a completely different approach to their intent handling, and usually find themselves using them in their own way as edge cases that better serve that kind of application component.

For those who would like to learn more about common intents and their intent filters, check out this list of common intents to try to find the best kind of implicit intents to integrate into your application.

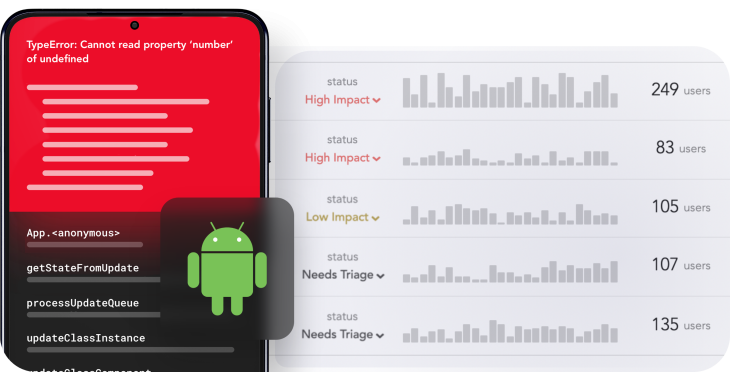

LogRocket is an Android monitoring solution that helps you reproduce issues instantly, prioritize bugs, and understand performance in your Android apps.

LogRocket's Galileo AI watches sessions for you, instantly identifying and explaining user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

LogRocket also helps you increase conversion rates and product usage by showing you exactly how users are interacting with your app. LogRocket's product analytics features surface the reasons why users don't complete a particular flow or don't adopt a new feature.

Start proactively monitoring your Android apps — try LogRocket for free.

Compare the top AI development tools and models of February 2026. View updated rankings, feature breakdowns, and find the best fit for you.

Broken npm packages often fail due to small packaging mistakes. This guide shows how to use Publint to validate exports, entry points, and module formats before publishing.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the February 11th issue.

Cut React LCP from 28s to ~1s with a four-phase framework covering bundle analysis, React optimizations, SSR, and asset/image tuning.

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now