The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

For frontend developers, JavaScript frameworks have become increasingly important due to how fundamentally they change the way we approach building our applications.

While not everyone uses them professional, or at all, the development community sure loves to talk about them. Unfortunately, these discussions often devolve into a diatribe about Framework X being better than Framework Y, or Framework Z not being “real JavaScript.”

As an engineer, I have always found it strange to think of one framework as “better” than another when they’re really all flavors of the same. Essentially, these tools are all trying to solve the same problems and improve the developer experience; they just take different approaches.

The intent of those building these frameworks is to empower developers to make better applications by making it easier for them to:

Sometimes it can feel like there is a hot new framework every other day (looking at you, Svelte), but React and Vue have been two of the most popular in recent years. Both are widely used at scale and have large, active open source communities.

As a React developer at Guru, I primarily work with React. However, I have recently been working with a local Vue meetup to coordinate the use of our office space for their events. Having not built anything with Vue in a while, I decided this would be the perfect opportunity to build something cool and re-familiarize myself, with the added benefit of comparing it to React.

Before we go any further, I just want to say: this article is not intended to determine whether React or Vue is better than the other. Instead, I hope to examine both frameworks in a practical sense and see how they differ when it comes to solving common problems. Examining another framework can even inform us of how to better use our own.

I recently bought a house and moved to a new neighborhood, so I no longer have access to the subway and must rely on the bus system to get to work. While having some time to read on my slightly longer commute can be nice, standing outside for a bus that never seems to come is not.

This seemed like a problem for which I could build a solution using Vue. Even though I could easily check SEPTA’s website or Google Maps (more on this later), I wanted to create a simple app that would tell me how much time I had until the next bus so I could quickly check it and run out the door.

Since there are more aspects to any given framework than can be covered in this article, we are going to focus on the difference I encountered while trying to achieve the goals of this small project:

Side note: My local transit authority did not have a solid API, so I ultimately ended up having to rely on Google Maps. To prevent tons of API calls, I set up a timed job to hit the API and then write a JSON file to cloud storage. This JSON is the data the app uses to render.

In the end, the application ended up looking like this:

Brew Bus

Brew Bus by ryancharris using axios, query-string, vue

As we discussed earlier, React and Vue both have similar goals but differ slightly in their approach. When I say approach, I am referring to the way in which you, the developer, go about building your components.

Of the two frameworks, Vue takes a more template-like approach, not dissimilar from the markup and templating tools used with Model-View-Controller frameworks in other languages like Ruby, Elixir, and PHP.

React, on the other hand, feels a bit more like HTML-in-JavaScript. Take a look at the two components below and see if you can figure out what’s happening.

First, with React:

function Accordion() {

const [isAccordionOpen, toggleAccordion] = React.useState(false);

return (

<div className="Accordion">

<h3>Accordion Header</h3>

<button

onClick={() => {

toggleAccordion(!isAccordionOpen);

}}

>

Toggle Accordion

</button>

{isAccordionOpen && <p>Accordion content lives here...</p>}

</div>

);

}

Now Vue:

<template>

<div class="accordion">

<button @click="toggleAccordion">Toggle Accordion</button>

<p v-if="isAccordionOpen">Accordion content lives here...</p>

</div>

</template>

<script>

export default {

name: "Accordion",

data: function() {

return {

isAccordionOpen: false

};

},

methods: {

toggleAccordion() {

this.isAccordionOpen = !this.isAccordionOpen;

}

}

};

</script>

One is not necessarily better than the other; they’re just different. And that’s what makes them so interesting!

Below, I’ve highlighted five tasks a developer commonly performs when building applications and created examples of how to achieve the desired outcome using either framework.

A common strategy developers use is called conditional rendering. Essentially, this is a fancy way of saying “if X, then Y.” This is often how we show or hide parts of our interface from the user.

We can see an example of this in App.vue within the <template> tags. Two of our components (<Work /> and <Home />) are being conditionally rendered using Vue’s v-bindings. In this case, the user sees <Work /> if our local state (i.e., data.isWorkScreen) has a value of true. Otherwise, they see, <Home />.

<div id="app">

<h1 class="app__header">{{createHeader}}</h1>

<Toggle @toggled="handleToggleChange"/>

<Work v-if="isWorkScreen"/>

<Home v-else/>

</div>

In React, we would do this slightly differently. There are a number of ways we could replicate the behavior seen above, but the most straightforward way would be to use an inline JSX expression right inside of the render function.

<div id="App">

<h1 className="App_header">My Cool App</h1>

<Toggle onClick={handleToggleChange} />

{isWorkScreen ? <Work /> : <Home />}

</div>

Another common thing I find myself doing when building an application is iterating through a data object and creating component instances for each item in the list. For example, this would be a good way to create every <Item /> in a <ToDoList />.

In our case, we’re creating two instances of <BusRoute /> in Work.vue and another two in Home.vue. In both files, we are iterating through our route information using the v-for binding in order to create each individual route component.

<div class="Work">

<BusRoute

v-for="bus in buses"

:key="`BusRoute-${bus.routeNumber}`"

:routeNumber="bus.routeNumber"

:origin="bus.origin"

:destination="bus.destination"

:jsonUrl="bus.jsonUrl"

/>

</div>

To replicate this in React, we can use something as simple as .map to create a <BusRoute /> for each item in our data object. Then, we can interpolate this value into the JSX tree we’re returning.

const { buses } = this.state;

const busRoutes = buses.map(bus => {

return (

<BusRoute

key={`BusRoute-${bus.routeNumber}`}

routeNumber={bus.routeNumber}

origin={bus.origin}

destination={bus.destination}

jsonUrl={bus.jsonUrl}

/>

)

})

return (

<div className="Work">

{busRoutes}

</div>

);

This one probably seems straightforward, and for the most part, it is. However, coming from a React background, there was one “gotcha” when it came to working with child components.

In React, this whole process is easy. You simply import the file and then use it in your renders.

Vue components require an extra step. In addition to importing and using child components, Vue components must locally register their component dependencies using the Vue instance’s component field. This overhead is intended to help with efficient bundling, thus reducing client download sizes.

App.vue would be the best example of this in our bus application as it is responsible for rendering three child components at various points in its lifecycle.

export default {

name: "App",

components: {

Home,

Toggle,

Work

}

}

Injecting data into your components in Vue is similar to how it was done in React before Hooks were released. Like React’s componentDidMount, Vue has a similar lifecycle method called created, which is where you would retrieve your data from an external source and ostensibly store it in local state.

Here’s what these two lifecycle methods look like one after the other.

React:

componentDidMount() {

axios({

method: "get",

url: this.props.jsonUrl

})

.then(res => {

const { routes } = res.data;

this.setState({

departureTime: routes[0].legs[0].departure_time.text

});

})

.catch(err => {

console.log(err);

});

}

Vue:

created: function(jsonUrl) {

axios({

method: "get",

url: this.$props.jsonUrl

})

.then(res => {

const { routes } = res.data;

this.departureTime = routes[0].legs[0].departure_time.text;

})

.catch(err => {

console.log(err);

});

}

And let’s not forget our new friend, Hooks! If you happen to be using React 16.8 (or newer), you may have already begun writing function components that use Hooks, so here’s how the above would be done in React going forward:

React.useEffect(() => {

axios({

method: "get",

url: props.jsonUrl

})

.then(res => {

const { routes } = res.data;

// setState is part of a useState hook unseen here

setRoute(routes[0].legs[0].departure_time.text);

})

.catch(err => {

console.log(err);

});

}, []);

Earlier we used the local state (i.e., data.isHomeScreen in App.vue) to determine whether the user saw the Home or Work child component. But how was this value changing? Great question!

If you looked at the Codesandbox, I’m sure you saw that Home and Work are not alone; they have a sibling called Toggle, which has some interesting markup we haven’t seen before.

<Toggle @toggled="handleToggleChange"/>

The @toggled=”handleToggleChange” is shorthand for another v-binding, v-on, which tells Vue to fire the local method handleToggleChange.

methods: {

handleToggleChange(newView) {

this.isWorkScreen = Boolean(newView === "work");

}

}

This function simply changes the local state to flip between the Home and Work screens. But what is toggled?

To answer this, we have to look inside the Toggle component. In the template, there are two ToggleButtons, both which have v-on:clicked bindings. These are essentially the equivalent of an onClick prop in React.

<template>

<div class="toggle">

<ToggleButton

@clicked="workClicked"

:class="{'toggle__button': true, 'active': workActive}"

text="Work"

/>

<ToggleButton

@clicked="homeClicked"

:class="{'toggle__button': true, 'active': homeActive}"

text="Home"

/>

</div>

</template>

Both of the callback functions toggle some local state, but the important part here is the last line of each function: this.$emit(...).

methods: {

workClicked() {

this.workActive = true;

this.homeActive = false;

this.$emit("toggled", "work");

},

homeClicked() {

this.workActive = false;

this.homeActive = true;

this.$emit("toggled", "home");

}

}

Notice the first argument, “toggled”. Essentially, this line triggers an event that App is now listening for due to the @toggled binding we added above.

In React, we do something similar, but instead of listening for an event emitted from the child, we pass a function prop from parent to child and execute that function inside the local event listener within the child component.

function Child(props) {

return (

<div>

<button onClick={() => props.toggleView("work")}>

Work

</button>

<button onClick={() => props.toggleView("home")}>

Home

</button>

</div>

);

}

function Parent() {

const [isWorkView, setWorkView] = React.useState(true);

return <Child toggleView={setWorkView} />;

}

Again, the result here is the same: a child component is manipulating the state of its parent.

Building an app, even one this small, in a framework other than React was an interesting exercise for a couple reasons. Not only did I gain experience working with another framework, but I was also forced to think in a non-React way for the first time since I started using it.

This, perhaps, is the most important thing to take away: it is important to explore other technologies to help us think outside the box our usual tools have put us in. Though I think I still prefer React, I don’t think I can say it’s better than Vue — just different.

Here are some other thoughts I had after going through this process:

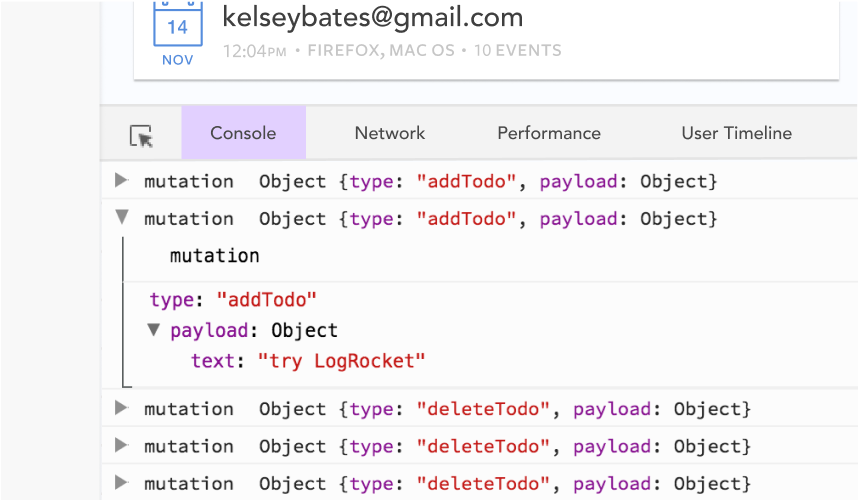

Debugging Vue.js applications can be difficult, especially when users experience issues that are difficult to reproduce. If you’re interested in monitoring and tracking Vue mutations and actions for all of your users in production, try LogRocket.

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings — compatible with all frameworks.

With Galileo AI, you can instantly identify and explain user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

Modernize how you debug your Vue apps — start monitoring for free.

Install LogRocket via npm or script tag. LogRocket.init() must be called client-side, not

server-side

$ npm i --save logrocket

// Code:

import LogRocket from 'logrocket';

LogRocket.init('app/id');

// Add to your HTML:

<script src="https://cdn.lr-ingest.com/LogRocket.min.js"></script>

<script>window.LogRocket && window.LogRocket.init('app/id');</script>

@container scroll-state: Replace JS scroll listeners nowCSS @container scroll-state lets you build sticky headers, snapping carousels, and scroll indicators without JavaScript. Here’s how to replace scroll listeners with clean, declarative state queries.

Explore 10 Web APIs that replace common JavaScript libraries and reduce npm dependencies, bundle size, and performance overhead.

Russ Miles, a software development expert and educator, joins the show to unpack why “developer productivity” platforms so often disappoint.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the February 18th issue.

Would you be interested in joining LogRocket's developer community?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now