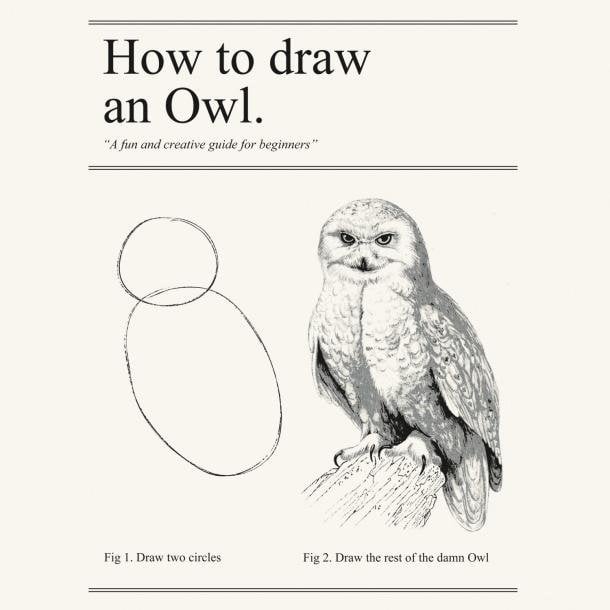

This is probably a topic that has been beaten to death since Node.js and (especially) Socket.io were released. The problem I see is most of the articles out there tend to stay above the surface of what a chat server should do and even though they end up solving the initial predicament, it is such a basic use case that taking that code and turning it into a production-ready chat server is the equivalent of the following image:

So instead of doing that, in this article, I want to share with you an actual chat server, one that is a bit basic due to the restrictions of the medium, mind you, but one that you’ll be able to use from day one. One that in fact, I’m using already in one of my personal projects.

But first, let’s quickly review what is needed for a chat server to indeed, be useful. Leaving aside your particular requirements, a chat server should be capable of doing the following:

That is the extent of what our little chat server will be capable of doing.

For the purposes of this article, I will create this server as a back-end service, able to work without a defined front end and I will also create a basic HTML application using jQuery and vanilla JavaScript.

Now that we know what the chat server is going to be doing, let’s define the basic interface for it. Needless to say, the entire thing will be based on Socket.io, so this tutorial assumes you’re already familiar with the library. If you aren’t though, I strongly recommend you check it out before moving forward.

With that out of the way, let’s go into more details about our server’s tasks:

The way I’ll structure the code, is by creating a single class called ChatServer , inside it, we can abstract the inner workings of the socket, like this:

// Setup basic express server

const config = require("config");

const ChatServer = require("./lib/chat-server")

const port = process.env.PORT || config.get('app.port');

// Chatroom

let numUsers = 0;

const chatServer = new ChatServer({

port

})

chatServer.start( socket => {

console.log('Server listening at port %d', port);

chatServer.onMessage( socket, (newmsg) => {

if(newmsg.type = config.get("chat.message_types.generic")) {

console.log("New message received: ", newmsg)

chatServer.distributeMsg(socket, newmsg, _ => {

console.log("Distribution sent")

})

}

if(newmsg.type == config.get('chat.message_types.private')) {

chatServer.sendMessage(socket, newmsg, _ => {

console.log("PM sent")

})

}

})

chatServer.onJoin( socket, newUser => {

console.log("New user joined: ", newUser.username)

chatServer.distributeMsg(socket, newUser.username + ' has joined !', () => {

console.log("Message sent")

})

})

})

Notice how I’m just starting the server, and once it’s up and running, I just set up two different callback functions:

Let me show you now how the methods from the chat server were implemented.

To make a long story short, a socket is a persistent bi-directional connection between two computers, usually, one acting as a client and other acting as a server ( in other words: a service provider and a consumer).

There are two main differences (if we keep to the high level definition I just gave you) between sockets and the other, very well known method of communication between client and server (i.e REST APIs):

That being said, the following code tries to simplify the logic needed by Socket.io to handle and manage socket connections:

let express = require('express');

let config = require("config")

let app = express();

let socketIO = require("socket.io")

let http = require('http')

module.exports = class ChatServer {

constructor(opts) {

this.server = http.createServer(app);

this.io = socketIO(this.server);

this.opts = opts

this.userMaps = new Map()

}

start(cb) {

this.server.listen(this.opts.port, () => {

console.log("Up and running...")

this.io.on('connection', socket => {

cb(socket)

})

});

}

sendMessage(socket, msgObj, done) {

// we tell the client to execute 'new message'

let target = msgObj.target

this.userMaps[target].emit(config.get("chat.events.NEWMSG"), msgObj)

done()

}

onJoin(socket, cb) {

socket.on(config.get('chat.events.JOINROOM'), (data) => {

console.log("Requesting to join a room: ", data)

socket.roomname = data.roomname

socket.username = data.username

this.userMaps.set(data.username, socket)

socket.join(data.roomname, _ => {

cb({

username: data.username,

roomname: data.roomname

})

})

})

}

distributeMsg(socket, msg, done) {

socket.to(socket.roomname).emit(config.get('chat.events.NEWMSG'), msg);

done()

}

onMessage(socket, cb) {

socket.on(config.get('chat.events.NEWMSG'), (data) => {

let room = socket.roomname

if(!socket.roomname) {

socket.emit(config.get('chat.events.NEWMSG'), )

return cb({

error: true,

msg: "You're not part of a room yet"

})

}

let newMsg = {

room: room,

type: config.get("chat.message_types.generic"),

username: socket.username,

message: data

}

return cb(newMsg)

});

socket.on(config.get('chat.events.PRIVATEMSG'), (data) => {

let room = socket.roomname

let captureTarget = /(@[a-zA-Z0-9]+)(.+)/

let matches = data.match(captureTarget)

let targetUser = matches[1]

console.log("New pm received, target: ", matches)

let newMsg = {

room: room,

type: config.get("chat.message_types.private"),

username: socket.username,

message: matches[2].trim(),

target: targetUser

}

return cb(newMsg)

})

}

}

The start method takes care of starting the socket server, using the Express HTTP server as a basis (this is a requirement from the library). There is not a lot more you can do here, the result of this initialization will be a call to whatever callback you set up on your code. The point here is to ensure you can’t start doing anything until the server is actually up and running (which is when your callback gets called).

Inside this callback, we set up a handler for the connection event, which is the one that gets triggered every time a new client connects. This callback will receive the actual socket instance, so we need to make sure we keep it safe because that’ll be the object we’ll use to communicate with the client application.

As you noticed in the first code sample, the socket actually gets passed as the first parameter for all methods that require it. That is how I’m making sure I don’t overwrite existing instances of the socket created by other clients.

After the socket connection is established, client apps need to manually join the chat and a particular room inside it. This implies the client is sending a username and a room name as part of the request, and the server is, among other things, keeping record of the username-socket pairs in a Map object. I’ll show you in a second the need for this map, but right now, that is all we take care of doing.

The join method of the socket instance makes sure that particular socket is assigned to the correct room. By doing this, we can limit the scope of broadcast messages (those that need to be sent to every relevant user). Lucky for us, this method and the entire room management logistics are provided by Socket.io out of the box, so we don’t really need to do anything other than using the methods.

This is probably the most complex method of the module, and as you’ve probably seen, it’s not that complicated. This method takes care of setting up a handler for every new message received. This could be interpreted as the equivalent of a route handler for your REST API using Express.

Now, if we go down the abstraction rabbit hole you’ll notice that sockets don’t really understand “messages”, instead, they just care about events. And for this module, we’re only allowing two different event names, “new message” and “new pm”, to be a message received or sent event, so both server and client need to make sure they use the same event names. This is part of a contract that has to happen, just like how clients need to know the API endpoints in order to use them, this should be specified in the documentation of your server.

Now, upon reception of a message event we do similar things:2

Once that is done, we create a JSON payload and pass it along to the provided callback. So basically, this method is meant to receive the message, check it, parse it and return it. There is no extra logic associated to it.

Whatever logic is needed after this step, will be inside your custom callback, which as you can see in the first example takes care distributing the message to the correct destination based on the type (either doing a broadcast to everyone on the same chat room) or delivering a private message to the targeted user.

Although quite straightforward, the sendMessage method is using the map I originally mentioned, so I wanted to cover it as well.

The way we can deliver a message to a particular client app (thus delivering it to the actual user) is by using the socket connection that lives between the server and that user, which is where our userMaps property comes into play. With it, the server can quickly find the correct connection based on the targeted username and use that to send the message with the emit method.

This is also something that we don’t really need to worry about, Socket.io takes care of doing all the heavy lifting for us. In order to send a message to the entire room skipping the source client (basically, the client that sent the original message to the room) is by calling the emit method for the room, using as a connection source the socket for that particular client.

The logic to repeat the message for everyone on the room except the source client is completely outside our control (just the way I like it! ).

That’s right, there is nothing else relevant to cover for the code, between both examples, you have all the information you need to replicate the server and start using it in your code.

I’ll leave you with a very simple client that you can use to test your progress in case you haven’t done one before:

const io = require('socket.io-client')

// Use https or wss in production.

let url = 'ws://localhost:8000/'

let usrname = process.argv[2] //grab the username from the command line

console.log("Username: ", usrname)

// Connect to a server.

let socket = io(url)

// Rooms messages handler (own messages are here too).

socket.on("new message", function (msg) {

console.log("New message received")

console.log(msg)

console.log(arguments)

})

socket.on('connect', _ => {

console.log("CONNECTED!")

})

socket.emit("new message", "Hey World!")

socket.emit("join room", {

roomname: "testroom",

username: usrname

})

socket.emit("new message", 'Hello there!')

This is a very simple client, but it covers the message sending and the room joining events. You can quickly edit it to send private messages to different users or add input gathering code to actually create a working chat client.

In either case, this example should be enough to get your chat server jump-started! There are tons of ways to keep improving this, as is expected, since once of the main problems with it, is that there is no persistence, should the service die, upon being restarted, all connection information would be lost. Same for user information and room history, you can quickly add storage support in order to save that information permanently and then restore it during startup.

Let me know in the comments below if you’ve implemented this type of socket-based chat services in the past and what else have you done with it, I’d love to know!

Otherwise, see you on the next one!

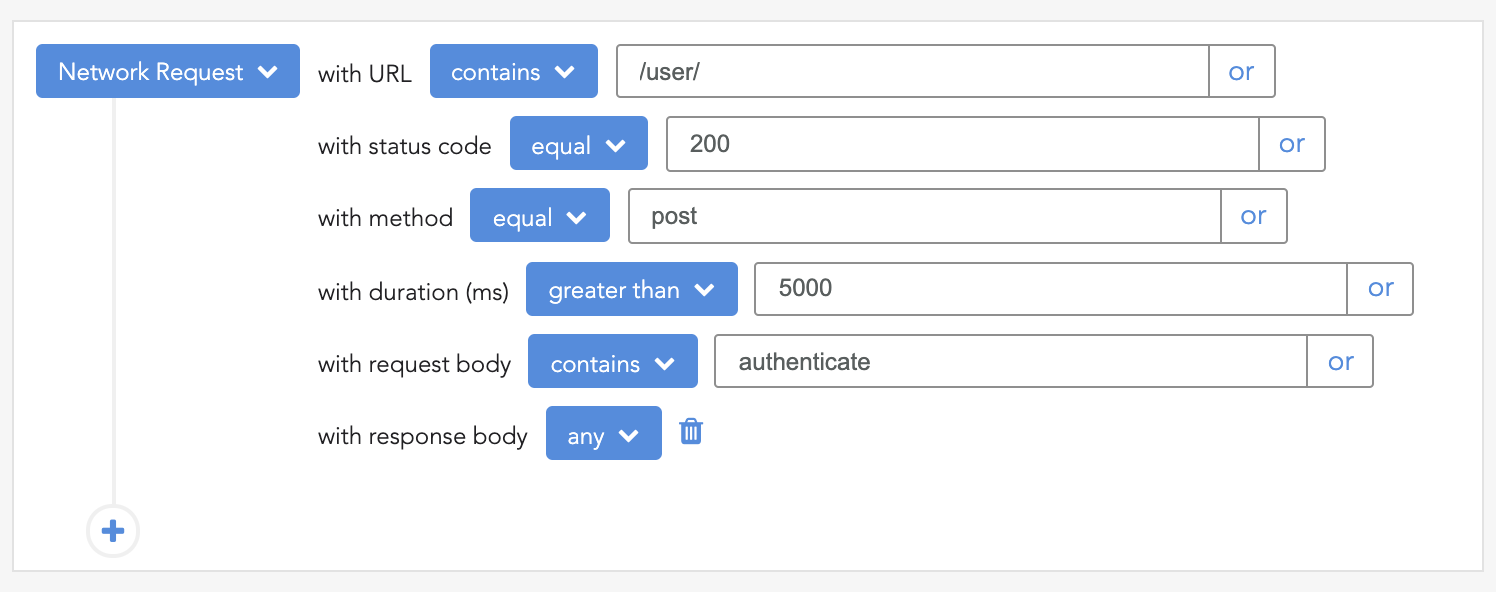

Monitor failed and slow network requests in production

Monitor failed and slow network requests in productionDeploying a Node-based web app or website is the easy part. Making sure your Node instance continues to serve resources to your app is where things get tougher. If you’re interested in ensuring requests to the backend or third-party services are successful, try LogRocket.

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork around why bugs happen by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings — compatible with all frameworks.

LogRocket's Galileo AI watches sessions for you, instantly identifying and explaining user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

LogRocket instruments your app to record baseline performance timings such as page load time, time to first byte, slow network requests, and also logs Redux, NgRx, and Vuex actions/state. Start monitoring for free.

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

This guide explores how to use Anthropic’s Claude 4 models, including Opus 4 and Sonnet 4, to build AI-powered applications.

Which AI frontend dev tool reigns supreme in July 2025? Check out our power rankings and use our interactive comparison tool to find out.

Learn how OpenAPI can automate API client generation to save time, reduce bugs, and streamline how your frontend app talks to backend APIs.

Discover how the Interface Segregation Principle (ISP) keeps your code lean, modular, and maintainable using real-world analogies and practical examples.

3 Replies to "Writing a working chat server in Node"

This is a nice breakdown of Socket chat servers. I’m currently doing something similar on a personal project. I also have events emitted when a user sends a friend request, accepts the request, etc.

Do you recommend storing that Socket instance to user ID map in a service like Redis? I’m thinking of ways to scale up my current implementation.

Hey O. Okeh, thanks for reading!

In regards to your question, it depends. If what you’re looking for is scaling up to accommodate more users, you need more instances running. +

I’m assuming you’ve created a dedicated chat service, which you should be able to clone.Then storing session information in Redis will help you more than storing the socket instance-user id map, because that way, your services can remain stateless, and clients can connect to any copy of your service (and any service will have access to the shared memory that Redis represents) without without losing session data.

So my recommendation would be to use Redis as a shared memory if that is what you need, and keep cloning your chat services with a possible load balancer in front of them.

Left the reply as a separate comment, by bad!