What is virtual scrolling and why do we need it? Imagine you have a dataset of 100,000 or more items you want to display as a scrollable list without pagination. Rendering that many rows would pollute the DOM, consume too much memory, and degrade the app’s performance.

Instead, you want to show the user only a small portion of data at a given time. Other items should be emulated (virtualized) via top and bottom padding elements, which are empty but have some height necessary to provide consistent scrollbar parameters. Each time the user scrolls out of the set of visible items, the content is rebuilt: new items are fetched and rendered, old ones are destroyed, padding elements are recalculated, etc.

That’s the virtual scrolling core principle in a nutshell. In this tutorial, we’ll go over the basics and learn how to create a reusable React component to solve the simplest virtual scrolling issues.

You can view the complete demo repository on my GitHub, and I’ve synced an app in CodeSandbox to play with it in runtime.

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

While there are myriad use cases and requirements associated with virtual scrolling, today we’ll focus on understanding the core principles and building a small component to satisfy some very basic requirements. Let’s define the conditions to start:

A first step toward any interface development can be to imagine how it could be used in the end. Let’s say we already have a component named VirtualScroller. To use it, we’ll need to do three things:

<VirtualScroller settings={SETTINGS} get={getData} row={rowTemplate}/>

We could provide settings as a set of separate HTML attributes, but instead we’ll define a single static object. Its fields should determine the desired behavior and reflect the initial conditions. Let’s start with minimal values (we can always increase maxIndex to 100,000).

const SETTINGS = {

minIndex: 1,

maxIndex: 16,

startIndex: 6,

itemHeight: 20,

amount: 5,

tolerance: 2

}

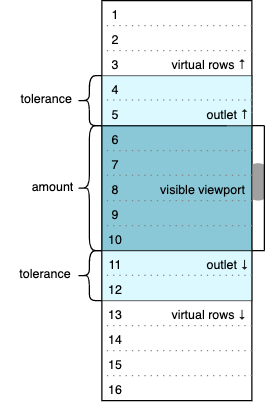

amount and tolerance require special attention. amount defines the number of items we want to be visible in the viewport. tolerance determines the viewport’s outlets, which contains additional items that will be rendered but invisible to the user. The diagram below represents the selected values of the SETTINGS object and the animated gif demonstrates how the initial state can change while scrolling.

The colored window contains real data rows (from 4 to 12 initially). The dark blue area represents a visible part of the viewport; its height is fixed and equal to amount * itemHeight. The light blue outlets have real but invisible rows because they are out of the viewport. White areas above and below are two empty containers; their height corresponds to virtualized rows that we don’t want to be present in the DOM. We can calculate the initial number of virtual rows as follows.

(maxIndex - minIndex + 1) - (amount + 2 * tolerance) = 16 - 9 = 7

Seven breaks into three virtual rows at the top and four virtual rows at the bottom.

The image changes each time we scroll up and down. For example, if we scroll to the very top (zero) position, the visible part of the viewport will have between one and five rows, the bottom outlet will have between six and seven rows, the bottom padding container will virtualize between eight and 16 rows, the top padding container will accept zero height, and the top outlet will not be present. The logic of such transitions is discussed below, and we’ll get to the VirtualScroller component in part two.

We defined the get property and passed it to the VirtualScroller component with the getData value. What is getData? It’s a method that provides a portion of our dataset to VirtualScroller. The scroller will request the data via this method, so we need to parameterize it with the appropriate arguments. Let’s call it offset and limit.

const getData = (offset, limit) => {

const data = []

const start = Math.max(SETTINGS.minIndex, offset)

const end = Math.min(offset + limit - 1, SETTINGS.maxIndex)

if (start <= end) {

for (let i = start; i <= end; i++) {

data.push({ index: i, text: `item ${i}` })

}

}

return data

}

The getData(4, 9) call means we want to receive nine items started from index 4. This particular call correlates with the diagram above: 4 to 12 items are needed to fill the viewport with outlets on start. With the help of Math.min and Math.max, we’ll restrict a requested data portion to fall within the dataset boundaries defined by the max/min index settings. This is also where we generate items; one item is an object with index and text properties. index is unique because these properties will take part in the row template.

Instead of generating items, we can request data from somewhere else, even from a remote source. We could return Promise to handle async data source requests, but for now we’ll focus on virtualizing rather than data flow to keep the implementation as simple as possible.

A very simple template that just displays the text property might look like this:

const rowTemplate = item =>

<div className="item" key={item.index}>

{ item.text }

</div>

The row template depends on the app’s unique needs. The complexity may vary, but it must be consistent with what getData returns. The row template’s item must have the same structure as each data list item. The key property is also required because VirtualScroller creates lists of rows and we need to provide a stable identity to the elements.

Let’s take another look:

<VirtualScroller settings={SETTINGS} get={getData} row={rowTemplate}/>

We’ve successfully passed the three things we wanted to pass to the VirtualScroller. This way, VirtualScroller does not have to know anything about the data it is dealing with. This information will come from outside the scroller via the get and row properties, which is key to the component’s reusability. We could also treat the agreement on the scroller properties we just set up as our future component API.

Now that half the work is done, on to phase two: building a virtual scroll component to satisfy the API we developed in the previous section. This might sound a little bit like how to draw an owl, but I promise, we really are halfway there.

Going back to the image from the previous section, it seems obvious that we’ll need the following DOM elements:

height and overflow-y: auto styleheightsdata items wrapped with row templatesrender() {

const { viewportHeight, topPaddingHeight, bottomPaddingHeight, data } = this.state

return (

<div className='viewport' style={{ height: viewportHeight }}>

<div style={{ height: topPaddingHeight }}></div>

{ data.map(this.props.row) }

<div style={{ height: bottomPaddingHeight }}></div>

</div>

)

}

This is what the render method might look like. Four state properties reflect the requirements we set up for the DOM structure: three heights and the current portion of data. Also, we see this.props.row, which is simply the row template passed from the outside, so data.map(this.props.row) will render a list of current data items in accordance with our API. We need to define the state props before we add scrolling.

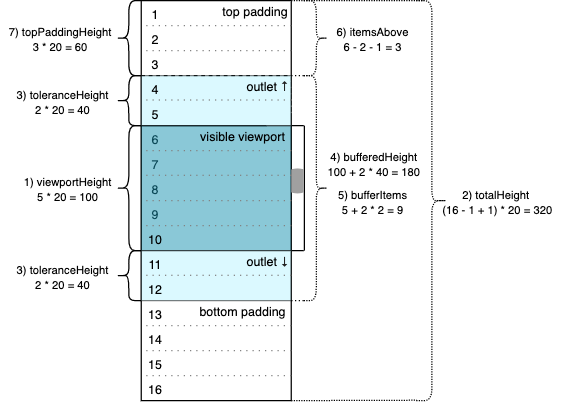

Now it’s time to initialize the inner component’s state. Let’s try to implement a pure function returning the initial state object based on the settings object discussed in part one. Along with the four state properties we put in render, we’ll need some other properties for scrolling so we won’t be surprised when the state object has a bit more props than needed for render. Having said that, our primary goal for this part is to force the initial picture to be drawn by the first render.

const setInitialState = ({

minIndex, maxIndex, startIndex, itemHeight, amount, tolerance

}) => {

// 1) height of the visible part of the viewport (px)

const viewportHeight = amount * itemHeight

// 2) total height of rendered and virtualized items (px)

const totalHeight = (maxIndex - minIndex + 1) * itemHeight

// 3) single viewport outlet height, filled with rendered but invisible rows (px)

const toleranceHeight = tolerance * itemHeight

// 4) all rendered rows height, visible part + invisible outlets (px)

const bufferHeight = viewportHeight + 2 * toleranceHeight

// 5) number of items to be rendered, buffered dataset length (pcs)

const bufferedItems = amount + 2 * tolerance

// 6) how many items will be virtualized above (pcs)

const itemsAbove = startIndex - tolerance - minIndex

// 7) initial height of the top padding element (px)

const topPaddingHeight = itemsAbove * itemHeight

// 8) initial height of the bottom padding element (px)

const bottomPaddingHeight = totalHeight - topPaddingHeight

// 9) initial scroll position (px)

const initialPosition = topPaddingHeight + toleranceHeight

// initial state object

return {

settings,

viewportHeight,

totalHeight,

toleranceHeight,

bufferHeight,

bufferedItems,

topPaddingHeight,

bottomPaddingHeight,

initialPosition,

data: []

}

}

Let’s take a look at the updated image:

Calculations (8) and (9) are not on the diagram. The scroller would not have any items in the buffer on initialization; the buffer remains empty until the first get method call returns a non-empty result. That’s also why we see an empty array [] as the data state property initial value. So the viewport should contain only two empty padding elements initially, and the bottom one should fill all the space that remains after the top one. Thus, 320 – 60 = 260 (px) would be the initial value of bottomPaddingHeight in our sample.

Finally, initialPosition determines the position of the scrollbar on start. It should be consistent with the startIndex value, so in our sample the scrollbar position should be fixed at the sixth row, top coordinate. This corresponds to 60 + 40 = 100 (px) value.

The initialization of the state is placed in the scroller component constructor, along with the creation of the viewport element reference, which is necessary to manually set the scroll position.

constructor(props) {

super(props)

this.state = setInitialState(props.settings)

this.viewportElement = React.createRef()

}

This enables us to initialize our viewport with two padding elements in which cumulative height corresponds to the volume of all the data we are going to show/virtualize. Also, the render method should be updated to assign the viewport element reference.

return (

<div className='viewport'

style={{ height: viewportHeight }}

ref={this.viewportElement}

> ... </div>

)

Right after the first render is done and the padding elements are initialized, set the viewport scrollbar position to its initial value. The DidMount lifecycle method is the right place for that.

componentDidMount() {

this.viewportElement.current.scrollTop = this.state.initialPosition

}

Now we have to handle scrolling. The runScroller method will be responsible for fetching data items and adjusting padding elements. We’ll implement that momentarily, but first let’s bind it with the scroll event of the viewport element on render.

return (

<div className='viewport'

style={{ height: viewportHeight }}

ref={this.viewportElement}

onScroll={this.runScroller}

> ... </div>

)

The DidMount method is invoked after the first render is done. Assigning the initialPosition value to the viewport’s scrollTop property will implicitly call the runScroller method. This way, the initial data request will be triggered automatically.

There’s also the edge case in which the initial scroll position is 0 and scrollTop won’t change; this is technically relevant to a situation where minIndex is equal to startIndex. In this case, runScroller should be invoked explicitly.

componentDidMount() {

this.viewportElement.current.scrollTop = this.state.initialPosition

if (!this.state.initialPosition) {

this.runScroller({ target: { scrollTop: 0 } })

}

}

We need to emulate the event object, but scrollTop is the only thing the runScroller handler will deal with. Now we have reached the last piece of logic.

runScroller = ({ target: { scrollTop } }) => {

const { totalHeight, toleranceHeight, bufferedItems, settings: { itemHeight, minIndex }} = this.state

const index = minIndex + Math.floor((scrollTop - toleranceHeight) / itemHeight)

const data = this.props.get(index, bufferedItems)

const topPaddingHeight = Math.max((index - minIndex) * itemHeight, 0)

const bottomPaddingHeight = Math.max(totalHeight - topPaddingHeight - data.length * itemHeight, 0)

this.setState({

topPaddingHeight,

bottomPaddingHeight,

data

})

}

runScroller is a class property of the scroller component (see also this issue I created in the TC39 repo) that has access to its state and props via this. It makes some calculations based on the current scroll position passed as an argument and the current state destructured in the first line of the body.

Lines 2 and 3 are for taking a new portion of the dataset, which will be a new scroller data items buffer. Lines 4 and 5 are for getting new values for the height of the top and bottom padding elements. The results go to the state and the render updates the view.

A few words on the math. In accordance with the API we developed in part one, the get method does require two arguments to answer the following questions.

limit argument, which is bufferedItems)?offset argument, which is index)?The index is calculated bearing in mind the top outlet, which results in the subtraction of the toleranceHeight value that was set before. Dividing by itemHeight leaves us with a number of rows before the index that we want to be first in the buffer. The addition of minIndex converts the number of rows to the index. Scroll position (scrollTop) can take place in the middle of random row and, in this way, may not be a multiple of itemHeight. That’s why we need to round the result of the division — index must be an integer.

The height of the top padding element is being taken via a number of rows before the index is multiplied by the known height of the row. The Math.max expression ensures that the result is not negative. We may shift this protection to the index step (say, index cannot be less than minIndex), but the result would be the same. It’s also worth noting that we already put such a restriction inside getData implementation.

The height of the bottom padding element takes into account the height of new items retrieved for the scroller buffer (data.length * itemHeight). I don’t believe it can be negative in this implementation, but we won’t worry about that for now. The logic is pretty basic, and we are trying to focus on the approach itself. As a result, some details might not be 100 percent perfect.

The history of virtual scroll engineering in frontend development dates back to the early 2010s, possibly earlier. My personal virtual scrolling journey started in 2014. Today, I maintain two Angular-universe repos — angular-ui-scroll and ngx-ui-scroll — and I used React to develop this simple demonstration.

The VirtualScroller component we just implemented can virtualize a fixed-size dataset, assuming the row height is constant. It consumes data using a special method that the developer is responsible for implementing. It also accepts the template and static settings properties that impact the view and behavior.

This article does not profess to be a source of absolute truth; it’s just an approach, one of many possible solutions suited for the simplest case. There are lots of all-inclusive solutions built on top of this or that framework, including React, but they all have their limitations and none truly cover all possible requirements. One library can always do something that another can’t — it’s a common situation.

Our abilities in applying the virtual scroll technique have been increased by the option to build a solution from scratch. It’s not sacred knowledge, but it’s something we can move on with.

Speaking of requirements, what other developments could we propose to make our implementation even better?

tolerance?min and max indexes can be unknownmaxIndex?That is by no means a complete list, and most of the features above have their own edge cases, various implementation methods, and performance and usability issues. And let’s not even get started about testing.

Also, each individual mouse, touchpad, phone, and browser could potentially behave differently, especially in the field of inertia. Sometimes I just want to cry. But for all the frustration associated with virtual scrolling, it’s also really fun and rewarding to develop. So get started today, and help carry the banner of virtual scrolling into a new age!

Install LogRocket via npm or script tag. LogRocket.init() must be called client-side, not

server-side

$ npm i --save logrocket

// Code:

import LogRocket from 'logrocket';

LogRocket.init('app/id');

// Add to your HTML:

<script src="https://cdn.lr-ingest.com/LogRocket.min.js"></script>

<script>window.LogRocket && window.LogRocket.init('app/id');</script>

Signal Forms in Angular 21 replace FormGroup pain and ControlValueAccessor complexity with a cleaner, reactive model built on signals.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the February 25th issue.

Explore how the Universal Commerce Protocol (UCP) allows AI agents to connect with merchants, handle checkout sessions, and securely process payments in real-world e-commerce flows.

React Server Components and the Next.js App Router enable streaming and smaller client bundles, but only when used correctly. This article explores six common mistakes that block streaming, bloat hydration, and create stale UI in production.

Would you be interested in joining LogRocket's developer community?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

16 Replies to "Virtual scrolling: Core principles and basic implementation in React"

Nice idea with custom component.. But Just wonder what changes should we do if we want the scroll for whole window not for a scrollable div and elements inside.

Thanks

Hey! I just made quick demo for the entire window case based on the original approach:

https://codesandbox.io/s/dhilt-react-virtual-scrolling-entire-window-hr9fc

I tried to persist basic ideas, but you’ll see some differences:

– react onScroll event had been replaced with plain old addEventListener of global “window”, and we rely on window.scrollY now;

– “amount” setting is gone due to window height might be random; now it is calculated as window.innerHeight / itemHeight rounded down; I’m pretty sure, it would be better if we’d change the concept and move to fractional approach, but this is cheaper, more consistent with previous version and still works;

– class component had been turned into a functional one; this.state and didMount are replaced with useState and useEffect; they are performant, no extra calls.

“`

// 8) initial height of the bottom padding element (px)

const bottomPaddingHeight = totalHeight – topPaddingHeight

“`

From the name, ‘topPaddingHeight’ and ‘bottomPaddingHeight’ have similar meanings. I think ‘bottomPaddingHeight’ is height of ‘bottom-virtual-rows’. So, bottomPaddingHeight = totalHeight – topPaddingHeight – viewportHeight – 2*toleranceHeight.

Looking forward to your reply.

I’m trying to put the example (from codesandbox) you provided into my MVC application. First I have to use type=”text/babel” in script tags when I add them into HTML page. Second, when I’m running the site then, I see that it fails with:

VM3783:3 Uncaught ReferenceError: exports is not defined

at :3:23

at i (babel.min.js:24)

at r (babel.min.js:24)

at e.src.n..l.content (babel.min.js:24)

at XMLHttpRequest.n.onreadystatechange (babel.min.js:24)

Can you please help?

UPD: Solved the issue above. Another question – how can I link the grid to depend on the parent element scroll event, but not the entire window? The grid will be a certain height with a scroll, and when I mouse scroll inside the element, or move the scroll control on the right, then scroll event shall fire.

It looks like a compile error. Don’t know what the infrastructure you are trying to build, I would suggest to look at the configuration on the github repo (link at the top of the article) as it provides pretty common way of compiling and running ReactJS application. The sample has no any additional external dependencies, only React core, so the question could be asked as following: “how to run simplest ReactJS application”.

Have you considered adding multiple columns / headers to the sample, with ability to sort columns?

Just to clarify, why are we copying the settings from the props to the state? I don’t think we are ever setting `settings` state internally, right? Nor would we even in more complex implementations. Thanks!

Agree. Basically, we are initializing state with props, and, there should be copying by value instead of reference, like { settings: { …settings }, … }. This should provide immutability for outer settings. Then we could think on listening for the props.settings change and provide state recalculation.

Hi!

I’ve implemented this but sometimes when I start scrolling at some point scroll kinda loops and keeps going down and padding keeps growing bigger automatically. Any ideas on what the issue may be?

Hello! Something is wrong with padding elements calculation. Post your issue here https://github.com/dhilt/react-virtual-scrolling and provide it with a demo on stackblitz, codesandbox or whatever. I’ll take a look and help to fix!

This is one of the best and simplest virtual scroller I used. I transformed in Angular, to avoid using Angular CDK. Well done.

Great! Would be nice if you share your implementation 🙂

Can you pls post github repo where you transformed this in Angular ?

Can you pls post the github repo here with the transformed version in Angular ?

That’s was great with virtualized DOM in ReactJS. The first i thank you for explain feature so detailed. It seem like if i have a div above virtualized container (i’m using window scroll with your example). And it like loop data when i rendering items. Additional, topPaddingHeight calculates wrong with empty space, which is the same height with a div above. Hope you see my comment :((((