User personas are a fundamental part of UX design projects. They help us empathize with users, prioritize pain points and solutions, and store research learnings in a digestible format.

But not everyone is familiar with proto-personas. They’re, to say the least, a great tool in a designer’s toolset. Worse yet, some people confuse personas with proto-personas. Although similar, there are a few critical differences that, when ignored, can cause more chaos than good.

So, in this blog, I save you the chaos. I’ll talk about proto-personas — what they are, when and why to use them, and how they differ from typical user personas.

A standard user persona is a snapshot summarizing key characteristics of a specific segment of users we are designing for. It includes information such as demographics, key pain points and needs, preferences, and skills.

Personas serve as a guiding light throughout the design process, helping ensure we’re designing for specific users, not for ourselves.

A proto-persona, on the other hand, may look identical to a traditional persona with similar content. But the difference comes in how they’re created.

A user persona is rooted in research and validated information about the user. A mixture of qualitative and quantitative research methods contributes to creating a well-informed, research-backed persona.

Proto personas, however, are not backed in research. They’re more of a collection of assumptions and beliefs about the particular user. Insights may support some of these assumptions, but generally, they are far from “confirmed evidence” and closer to beliefs.

If you have ever been involved in creating a user persona based on high-level thoughts, some basic desk research, and stakeholders’ opinions, you actually created a proto persona.

I’ll put it simply — a proto-persona is, in fact, an inferior version of a proper user persona. But there are some major benefits of using proto-personas, which make them a tool worth considering:

If you don’t have solid research on your target audience, starting with a hypothetical proto persona is still better than having nowhere to begin.

Even an assumptions- and beliefs-driven persona will guide you on where to focus next and help you prioritize your user research and design decisions accordingly.

Regardless, though, the sooner you switch from proto persona to real personas, the better.

With proto-personas, you can identify and prioritize. Think of answers to questions like:

Creating a proto-persona can actually speed up the process of building a fully developed user persona.

Building a proto-persona doesn’t take much time or cost. All you need to do is gather a few informed people in one room and discuss and “assume” the characteristics of your audience.

It might sound like it’s not ideal, but if your resources are tight, you’re better off working with a proto persona than not having a persona at all. Even if your design fails, you’ll be able to point out which proto-persona assumptions didn’t work and require revisions.

To put everything in context, I’ll now share an example of when using a proto persona helped us immensely,

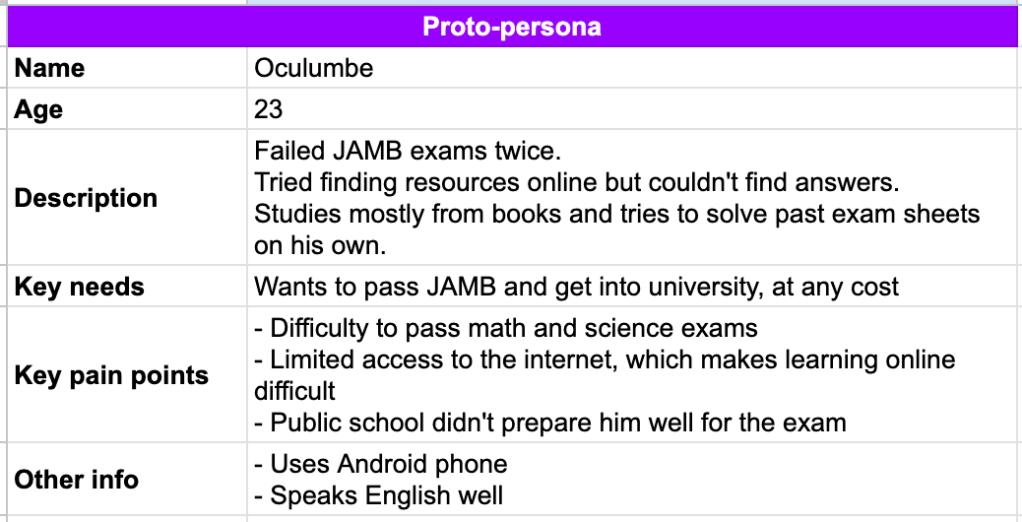

My team was developing an EdTech mobile app that aimed to help students in Nigeria pass their university entrance exams.

We didn’t have strong research on our target audience and were under pressure to deliver before the next exam cycle. So, we started by gathering all the beliefs and assumptions.

We ended up with these insights into our end user:

We listed these assumptions and beliefs based on common knowledge and past experiences. They weren’t random guesses, but they weren’t validated statements either.

I am a huge proponent of a visual approach to creating UX artifacts. But a simple Excel template like this can help you structure your train of thought if you are looking for a quick starting point:

You might find information such as age or name superficial at this stage. However, if you are working with multiple (proto)personas simultaneously, this information will help create mental differentiation between them.

If you want to begin with something more robust, any standard user persona template will work.

Next, we began to prioritize which assumptions were

We were pretty confident that our user:

But we needed to be more confident in our subject focus. We weren’t sure if math and science were our best picks. And we knew these students were committed to passing the exam. But this assumption that they were willing to practice daily was essential for the product’s design, so we decided to validate that further.

Our next and last task was to validate the riskiest assumptions, update the proto-persona, and repeat the process.

After several interviews and surveys, we reinforced our belief that exam-takers are willing to practice daily. Surprisingly, though, we discovered that biology and chemistry were significantly more desirable subjects to pass than math and science. We also gathered a few other insights, which we added to the proto-persona for further validation.

We then continued work on developing our MVP (focusing on the most validated assumptions) while continuing our validation research around the proto-persona. This continuous iteration cycle helped us turn the proto-persona into an actual user persona step-by-step without needing all insights upfront.

Proto-personas are a great starting point and often better than a blank page. But they might not always be your best choice. I recommend avoiding them for a few situations:

When designing for a challenging project without much initial insight or even assumptions, you definitely need to put in hours for proper research.

Yes, proto-personas tend to speed up research by giving some guidance on structuring further research, but they might not be the best for complex and ambiguous challenges. You’ll likely be missing many important things.

Starting an exploratory project with an open mind is more efficient than putting preexisting assumptions into the picture.

There are situations when you can easily get access to important user data — say, if:

In such circumstances, you’re better off investing some extra time at the beginning to gather and use this data and starting with the proper persona from day one.

For projects where mistakes can have serious consequences — like designing interfaces for 911 dispatch or missile launches — there’s no room for error. In these cases, it’s essential to have fully validated user personas before proceeding.

Proto-personas are a great tool in each UX designer’s skillset. This assumption-driven first draft of an actual persona helps kickstart MVP explorations, structure research, prioritize assumptions, and give a sense of direction.

Be careful, though.

I’ve met too many designers who based strategic decisions on proto-personas. The more you use your proto-persona, the more “real” it begins to feel, and the easier it is to forget that it’s still a box of assumptions.

I like to add some funny warning signs to my proto-personas, such as “Warning! Everything here might be false!” to avoid that bias.

Over time, though, the more you iterate on your proto-persona based on actual evidence from actual research, the more real it’ll become, and at some point, it’s okay to start treating it as a fully-fledged persona.

If you can make mistakes, go fast, break things, and learn on the go.

But if a mistake is not an option, avoid proto-personas.

LogRocket's Galileo AI watches sessions and understands user feedback for you, automating the most time-intensive parts of your job and giving you more time to focus on great design.

See how design choices, interactions, and issues affect your users — get a demo of LogRocket today.

Discover how to craft UX-friendly hero sections with examples, design tips, and strategies that drive engagement and conversion.

While Apple’s Liquid Glass can’t yet be perfectly recreated with CSS or Figma, we can still think about how to adopt the effect thoughtfully in our designs.

Figma Make is here to automate your design-to-code workflow. I tested it. Let’s talk about the good, the bad, and the straight-up weird.

After designing AI search systems, I’ve seen what builds trust — and what kills it. Here’s my take on what really works.