There are two main types of mnemonic manifestations — meaning, memory is not a homogeneous phenomenon. We have recognition and recall.

We’ve discovered relevant publications dating back to 1913, like the study “Characteristic Differences between Recall and Recognition.” It highlights how, until then, scientists concentrated on recall, ignoring recognition. Since then, both terms were solidified as types of memory: Google Scholar notes over 83,000 studies on recognition and recall.

How can we apply these studies to UX design? We can leverage the correct modality of memory for our users to guide them to make decisions. Let me show you what I mean.

We nowadays settle on the definition that recognition is the ability to say that something is familiar while recall is the ability to remember specific information about it.

Another way of putting this is that recognition is the ability to distinguish something as having been experienced before while recall is the ability to remember specific details about that experience, and it focuses on the sixth point of the 10 Usability Heuristics for User Interface Design.

While considering recognition and recall for designing good digital products, keep in mind (no pun intended) that they are influenced by speed and cognitive load. We can easily track speed and cognitive load with UX KPIs because they impact aspects such as:

In addition to these KPIs related to speed and cognitive load, the proper use of techniques that trigger recognition and make good use of recall can positively affect:

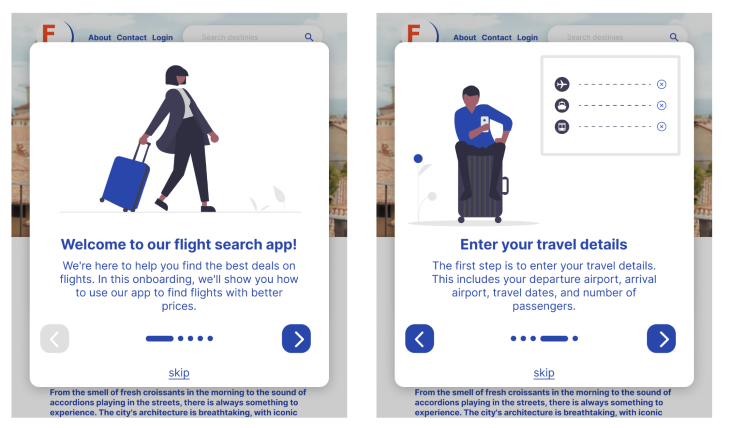

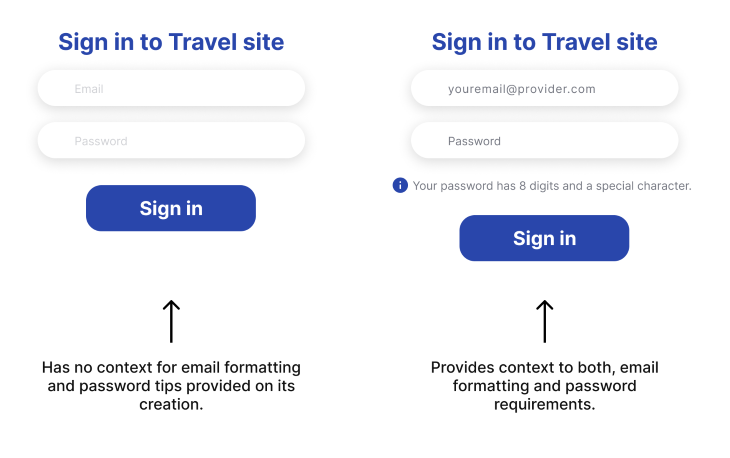

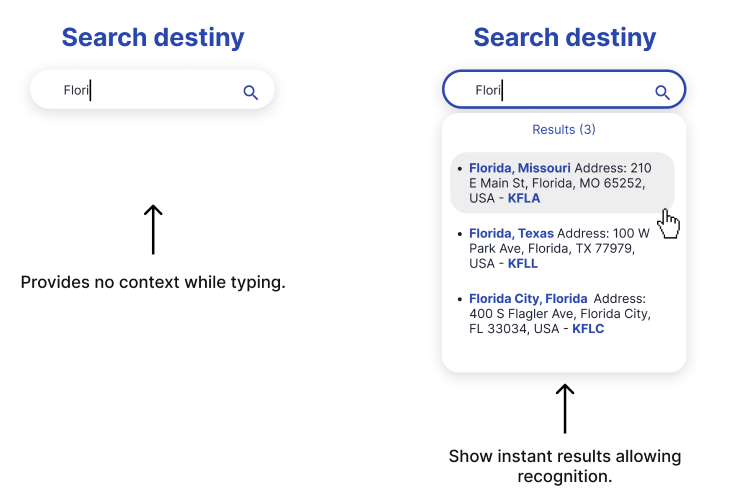

In the Usability Heuristics for User Interface Design, we read, “Recognition rather than recall,” and reasons abound. When users are faced with a task to perform, the less context they have to reconstruct through the process, the easier is the usability of such interfaces. This means that one of the most important aspects of the role of a UX designer is to provide users with signs that remind them of familiar experiences, rather than forcing them to remember (recall) contexts on how to make something.

Users should not have to be demanded to recall information because it means to build context and transfer it into action by itself. In the two-stage theory of memory (research and retrieve), it can be summarized as follows:

After that, it will be subjected to context, and a user will make a decision.

To recognize something, on the other hand, is to acknowledge that something is known because you are presented with partial elements of that one thing. We all know that feeling of “I know this,” even if you can’t remember how you know this. That is recalling in action.

A UX utopia would be a world in which designed applications are so friendly that they didn’t require retrieving information but only reacting to natural impulses. This is why natural language interfaces such as voice assistants are so highly valuable and, at the same time, so difficult to achieve.

In natural language, we reach a task starting from any familiarized phrase I have on my mind. For example, John and Mary both want to buy new shoes online:

For both, the system would consider purchase history in order to perform the task, but the inputs were highly personal approaches to the same question.

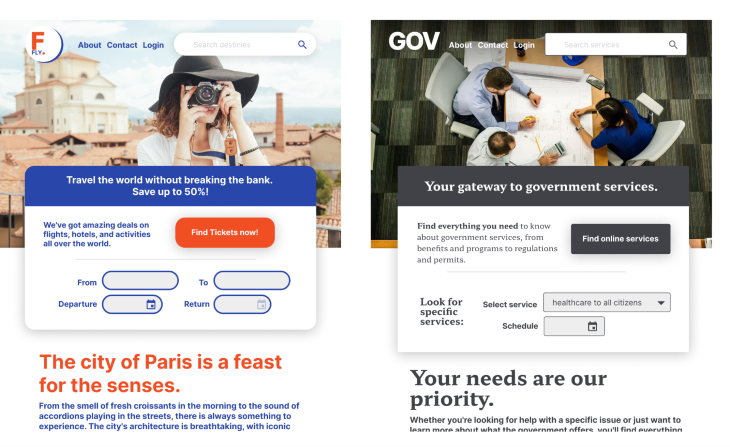

You can apply recognition techniques in user interfaces by good use of semiotics. Semiotics is the science that deals specifically with the forms of relations of things in cognitive processes. In semiotics, there are three main modes of relations:

If the UX designer knows its users, he or she can easily define which signs will be at the user’s disposal in order to provide instant recognition of known contexts.

Contextualizing an interface with cues or signs guides users to your intended behaviors. Let’s see some ways you can use recognition to evoke a response in users.

![]()

To recall is to build up information without context being given. In other words, recall asks you to retrieve information from memory without any cues being provided. We’ve spoken about why this is less ideal than recognition, but sometimes it’s necessary.

In user interfaces, recall is commonly related to open fields in forms, where the interface cannot provide sufficient information and it is fully dependent on the user’s memory. Open fields such as:

In order to register the effectiveness of using techniques for recognition instead of recall, we must center our KPIs around time to completion as a metric. We can subdivide “completion rate” as the percentage of people capable of finishing a proposed user journey (funneling) by measuring:

Your project needs clear usability tasks defined as tags to be tracked. Apart from that, developing systems that aim on recognition recall instead are hypotheses that can be evaluated with usability testing, more specifically A/B tests.

We can securely say that recognition and recall are fundamental cognitive processes in designing user interfaces. Prioritizing recognition over recall can lead to more efficient and user friendly digital products.

By understanding the importance of contextual cues, semiotics, and mental models, UX designers can create interfaces that facilitate recognition, ultimately enhancing the overall user experience. Usability testing and evaluation are crucial for validating the impact of recognition techniques and guiding future design decisions based on proven insights.

LogRocket's Galileo AI watches sessions and understands user feedback for you, automating the most time-intensive parts of your job and giving you more time to focus on great design.

See how design choices, interactions, and issues affect your users — get a demo of LogRocket today.

2FA has evolved far beyond simple SMS codes. This guide explores authentication methods, UX flows, recovery strategies, and how to design secure, frictionless two-factor systems.

Designing for background jobs means designing for uncertainty. Learn how to expose job states, communicate progress meaningfully, handle mixed outcomes, and test async workflows under real-world conditions.

There’s no universally “best” design language. This section breaks down when Linear-style design works well, how to build beyond it (or start from Radix UI), why it felt overused in SaaS marketing, and why conversion claims still need real testing.

Minimal doesn’t always mean usable. This comparison shows how Linear-style UI keeps contrast, affordances, and structure intact, unlike brutalism’s extremes or neumorphism’s low-clarity depth effects.