React Hooks were added to React in version 16.8. With the transition from class to functional components, Hooks let you use state and other features within functional components, i.e., without writing a class component.

useStateuseEffectuseContextuseReduceruseCallbackuseMemouseRefuseImperativeHandleuseLayoutEffectuseDebugValue

This reference guide will discuss all the Hooks natively available in React, but first, let’s start with the basic React Hooks: useState, useEffect, and useContext.

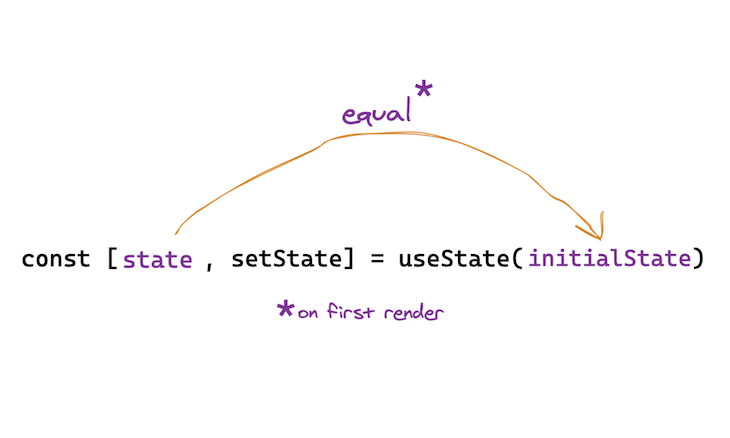

useStateThe signature for the useState Hook is as follows:

const [state, setState] = useState(initialState);

Here, state and setState refer to the state value and updater function returned on invoking useState with some initialState.

It’s important to note that when your component first renders and invokes useState, the initialState is the returned state from useState.

Also, to update state, the state updater function setState should be invoked with a new state value, as shown below:

setState(newValue)

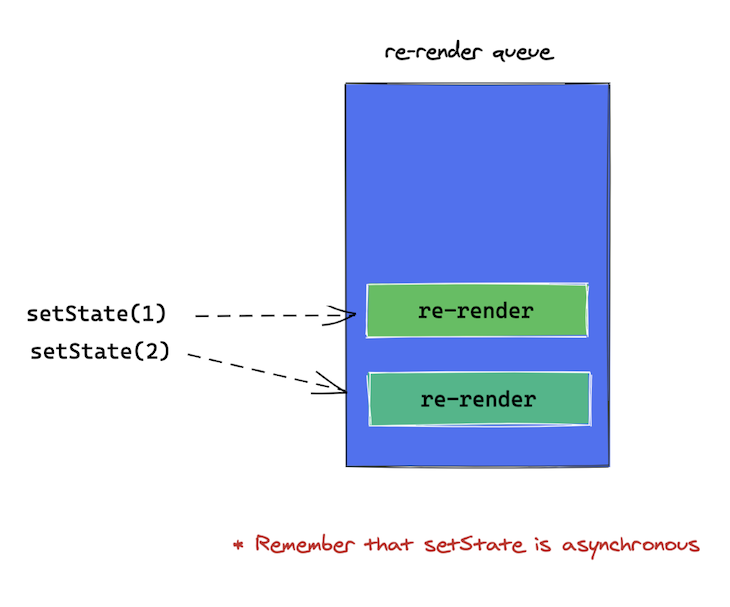

By doing this, a new re-render of the component is queued. useState guarantees that the state value will always be the most recent after applying updates.

For referential checks, the setState function’s reference never changes during re-renders.

Why is this important? It’s completely OK to have the updater function in the dependency list of other Hooks, such as useEffect and useCallback, as seen below:

useEffect(() => {

setState(5)

}, [setState]) //setState doesn't change, so useEffect is only called on mount.

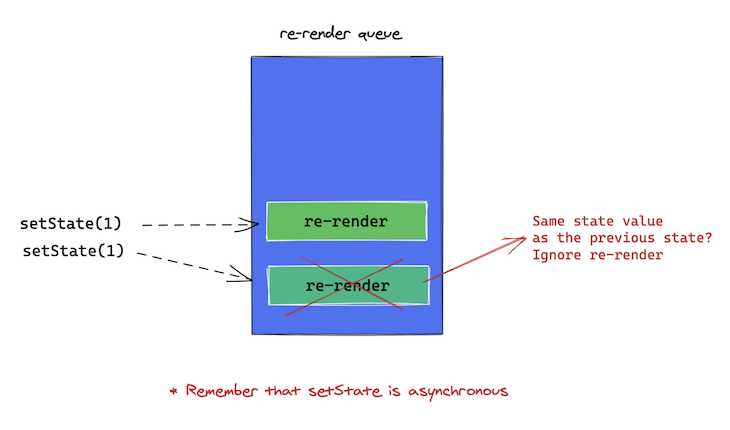

Note that if the updater function returns the exact same value as the current state, the subsequent re-render is skipped:

The state updater function returned by useState can be invoked in two ways. The first is by passing a new value directly as an argument:

const [state, setState] = useState(initialStateValue) // update state as follows setState(newStateValue)

This is correct and works perfectly in most cases. However, there are cases where a different form of state update is preferred: functional updates.

Here’s the example above revised to use the functional update form:

const [state, setState] = useState(initialStateValue) // update state as follows setState((previousStateValue) => newValue)

You pass a function argument to setState. Internally, React will invoke this function with the previous state as an argument. Whatever is returned from this function is set as the new state.

Let’s take a look at cases where this approach is preferred.

When your new state depends on the previous state value — e.g., a computation — favor the functional state update. Since setState is async, React guarantees that the previous state value is accurate.

Here’s an example:

function GrowingButton() {

const [width, setWidth] = useState(50);

// call setWidth with functional update

const increaseWidth = () => setWidth((previousWidth) => previousWidth + 10);

return (

<button style={{ width }} onClick={increaseWidth}>

I grow

</button>

);

}

In the example above, the button grows every time it’s clicked. Since the new state value depends on the old, the functional update form of setState is preferred.

Consider the following code block:

function CanYouFigureThisOut() {

const [state, setState] = useState({ name: "React" });

const updateState = () => setState({ creator: "Facebook" });

return (

<>

<pre>{JSON.stringify(state)}</pre>

<button onClick={updateState}>update state</button>

</>

);

}

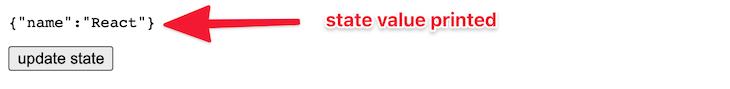

When you click the update state button, which of the state values below is printed?

//1.

{"name": "React", "creator": "Facebook"}

//2.

{"creator": "Facebook"}

//3.

{"name": "React"}

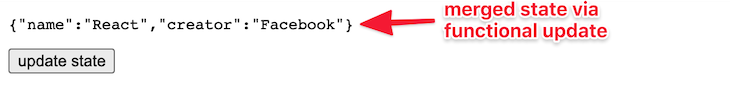

The correct answer is 2 because with Hooks, the updater function does not merge objects, unlike the setState function in class components. It replaces the state value with whatever new value is passed as an argument.

Here’s how to fix that using the functional update form of the state updater function:

const updateState = () => setState((prevState) => ({ ...prevState, creator: "Facebook" }));

Pass a function to setState and return a merged object by using the spread operator (Object.assign also works).

There are legitimate cases where you may include a state value as a dependency to useEffect or useCallback. However, if you’re getting needless fires from your useEffect callback owing to a state dependency used by setState, the updater form can alleviate the need for that.

See an example below:

const [state, setState] = useState(0)

// before

useEffect(() => {

setState(state * 10)

}, [state, setState]) //add dependencies to prevent eslint warning

// after: if your goal is to run the callback only on mount

useEffect(() => {

setState(prevState => prevState * 10)

}, [setState]) //remove state dependency. setState can be safely used here.

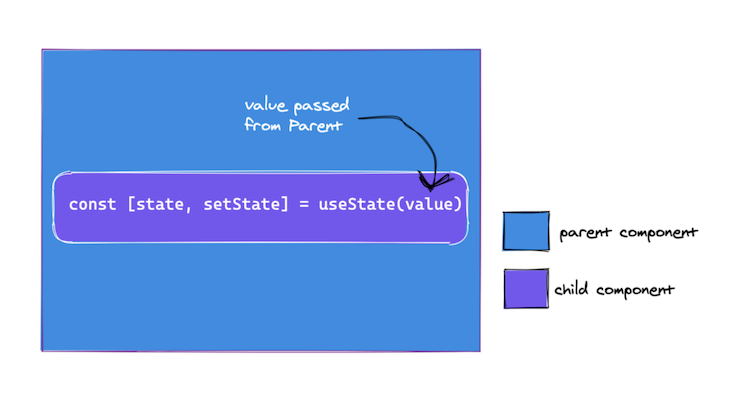

The initialState argument to useState is only used during your initial render.

// this is OK

const [state, setState] = useState(10)

// subsequent prop updates are ignored

const App = ({myProp}) => {

const [state, setState] = useState(myProp)

}

// only the initial myProp value on initial render is passed as initialState. subsequent updates are ignored.

However, if the initial state is a result of an expensive computation, you could also pass a function, which will be invoked only on initial render:

const [state, setState] = useState(() => yourExpensiveComputation(props))

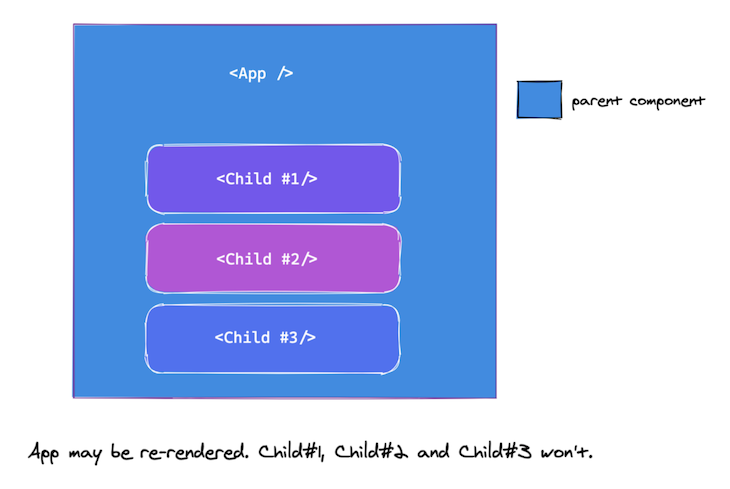

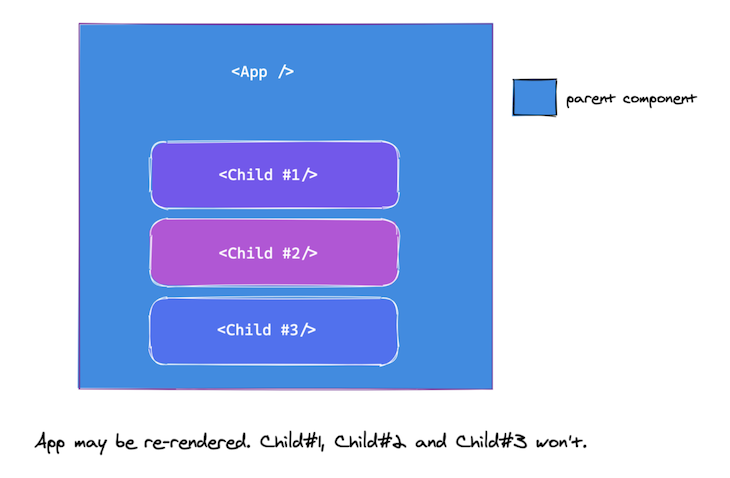

If you try to update state with the same value as the current state, React won’t render the component children or fire effects, e.g., useEffect callbacks. React compares previous and current state via the Object.is comparison algorithm; if they are equal, it ignores the re-render.

It’s important to note that in some cases, React may still render the specific component whose state was updated. That’s OK because React will not go deeper into the tree, i.e., render the component’s children.

If expensive calculations are done within the body of your functional component, i.e., before the return statement, consider optimizing these with useMemo.

useEffectThe basic signature of useEffect is as follows:

useEffect(() => {

})

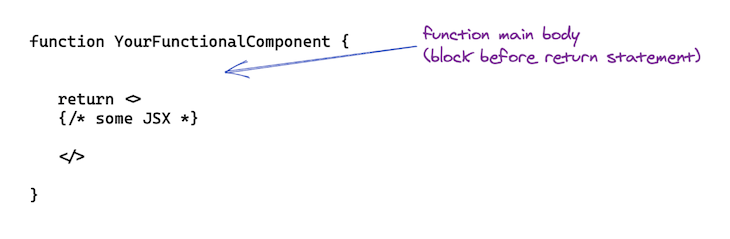

useEffect accepts a function that ideally contains some imperative, possibly effectual code. Examples include mutations, subscriptions, timers, loggers, etc. — essentially, side effects that aren’t allowed inside the main body of your function component.

Having such side effects in the main body of your function can lead to confusing bugs and inconsistent UIs. Don’t do this. Use useEffect.

The function you pass to useEffect is invoked after the render is committed to the screen. We’ll explain this in greater depth in a later section. For now, think of the callback as the perfect location to place imperative code within your functional component.

By default, the useEffect callback is invoked after every completed render, but you can choose to have this callback invoked only when certain values have changed — as discussed in a later section.

useEffect(() => {

// this callback will be invoked after every render

})

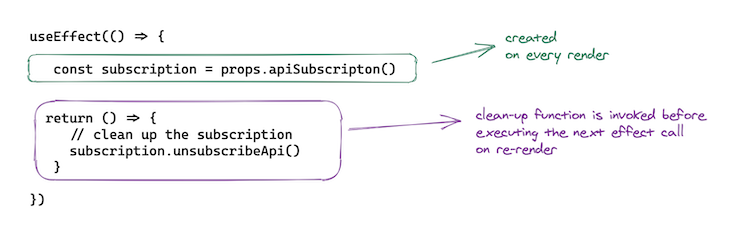

Some imperative code needs to be cleaned up. For example, subscriptions need to be cleaned up, timers need to be invalidated, etc. To do this, return a function from the callback passed to useEffect:

useEffect(() => {

const subscription = props.apiSubscription()

return () => {

// clean up the subscription

subscription.unsubscribeApi()

}

})

The cleanup function is guaranteed to be invoked before the component is removed from the user interface.

What about cases where a component is rendered multiple times, e.g., a certain component A renders twice? In this case, on first render, the effect subscription is set up and cleaned before the second render. In the second render, a new subscription is set up.

The implication of this is that a new subscription is created on every render. There are cases where you wouldn’t want this to happen, and you’d rather limit when the effect callback is invoked. Please refer to the next section for this.

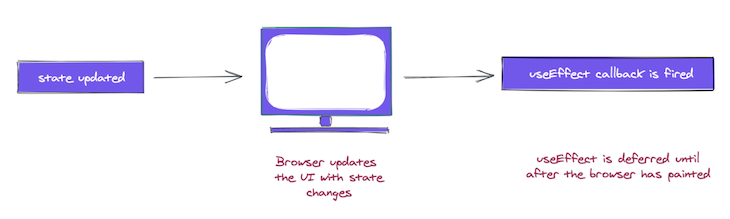

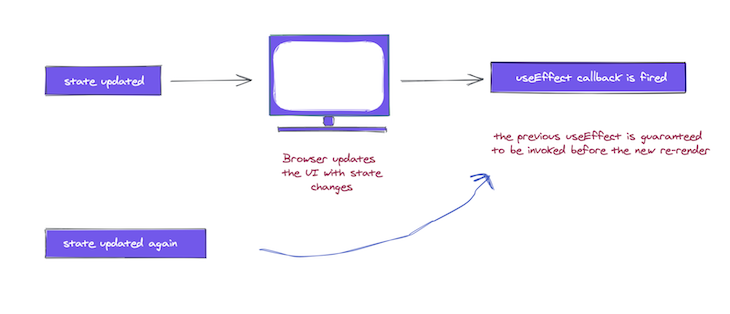

There’s a very big difference between when the useEffect callback is invoked and when class methods such as componentDidMount and componentDidUpdate are invoked.

The effect callback is invoked after the browser layout and painting are carried out. This makes it suitable for many common side effects, such as setting up subscriptions and event handlers since most of these shouldn’t block the browser from updating the screen.

This is the case for useEffect, but this behavior is not always ideal.

What if you wanted a side effect to be visible to the user before the browser’s next paint? Sometimes, this is important to prevent visual inconsistencies in the UI, e.g., with DOM mutations.

For such cases, React provides another Hook called useLayoutEffect. It has the same signature as useEffect; the only difference is in when it’s fired, i.e., when the callback function is invoked.

N.B., although

useEffectis deferred until the browser has painted, it is still guaranteed to be fired before any re-renders. This is important.

React will always flush a previous render’s effect before starting a new update.

By default, the useEffect callback is invoked after every render.

useEffect(() => {

// this is invoked after every render

})

This is done so that the effect is recreated if any of its dependencies change. This is great, but sometimes it’s overkill.

Consider the example we had in an earlier section:

useEffect(() => {

const subscription = props.apiSubscription()

return () => {

// clean up the subscription

subscription.unsubscribeApi()

}

})

In this case, it doesn’t make a lot of sense to recreate the subscription every time a render happens. This should only be done when props.apiSubscription changes.

To handle such cases, useEffect takes a second argument known as an array dependency.

useEffect(() => {

}, []) //note the array passed here

In the example above, we can prevent the effect call from running on every render as follows:

useEffect(() => {

const subscription = props.apiSubscription()

return () => {

// clean up the subscription

subscription.unsubscribeApi()

}

}, [props.apiSubscription]) // look here

Let’s take a close look at the array dependency list.

If you want your effect to run only on mount (clean up when unmounted), pass an empty array dependency:

useEffect(() => {

// effect callback will run on mount

// clean up will run on unmount.

}, [])

If your effect depends on some state or prop value in scope, be sure to pass it as an array dependency to prevent stale values being accessed within the callback. If the referenced values change over time and are used in the callback, be sure to place them in the array dependency, as seen below:

useEfect(() => {

console.log(props1 + props2 + props3)

},[props1, props2, props3])

Let’s say you did this:

useEffect(() => {

console.log(props1 + props2 + props3)

},[])

props1, props2, and props3 will only have their initial values and the effect callback won’t be invoked when they change.

If you skipped one of them, e.g., props3:

useEfect(() => {

console.log(props1 + props2 + props3)

},[props1, props2])

Then the effect callback won’t run when props3 changes.

The React team recommends you use the eslint-plugin-react-hooks package. It warns when dependencies are specified incorrectly and suggests a fix.

You should also note that the useEffect callback will be run at least once. Here’s an example:

useEfect(() => {

console.log(props1)

},[props1])

Assuming props1 is updated once, i.e., it changes from its initial value to another, how many times would you have props1 logged?

props1 changesprops1 changesThe correct answer is 3 because the effect callback is first fired after the initial render, and subsequent invocations happen when props1 changes. Remember this.

Finally, the dependency array isn’t passed as arguments to the effect function. It does seem like that, though; that’s what the dependency array represents. In the future, the React team may have an advanced compiler that creates this array automatically. Until then, make sure to add them yourself.

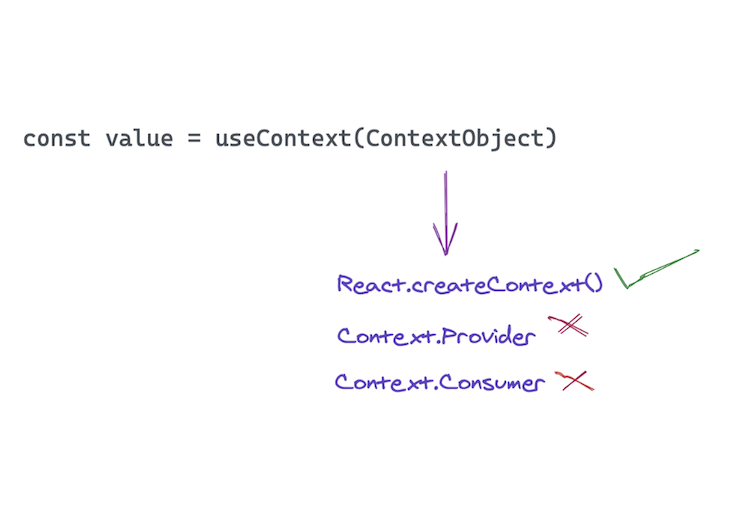

useContextHere’s how the useContext Hook is used:

const value = useContext(ContextObject)

Note that the value passed to useContext must be the context object, i.e., the return value from invoking React.createContext — not ContextObject.Provider or ContextObject.Consumer.

useContext is invoked with a context object (the result of calling React.createContext), and it returns the current value for that context.

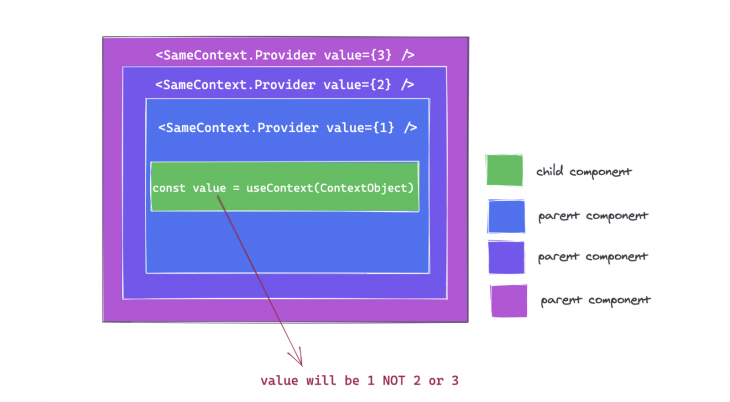

The value returned from useContext is determined by the value prop of the nearest Provider above the calling component in the tree.

Note that using the useContext Hook within a component implicitly subscribes to the nearest Provider in the component tree, i.e., when the Provider updates, this Hook will trigger a serenader with the latest value passed to that Provider.

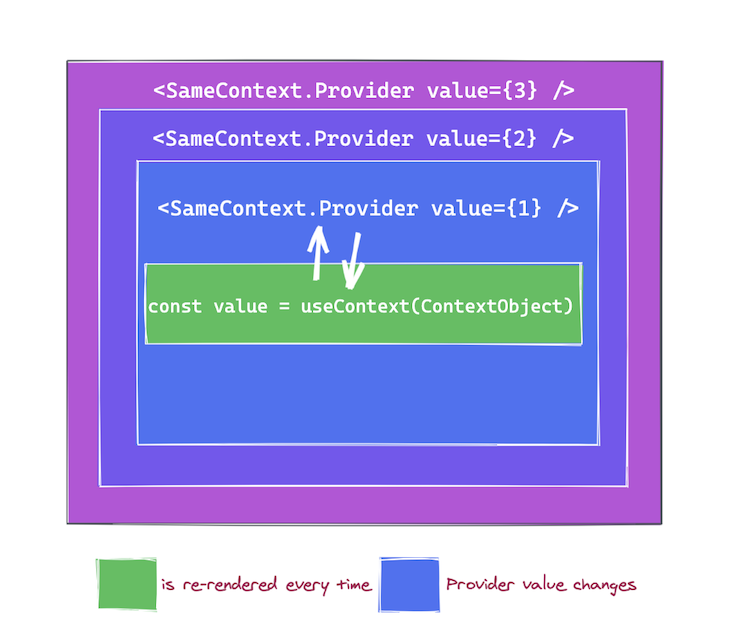

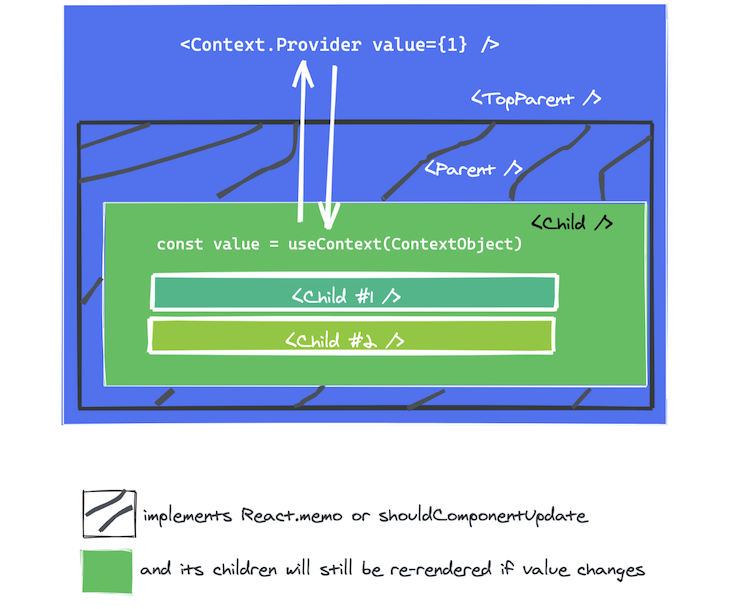

Here’s an even more important point to remember. If the ancestor component uses React.memo or shouldComponentUpdate, a re-render will still happen starting at the component that calls useContext.

A component calling useContext will be re-rendered when the context value changes. If this is expensive, you may consider optimizing it by using memoization.

Remember that useContext only lets you read the context and subscribe to its changes. You still need a context provider, i.e., ContextObject.Provider, above in the component tree to provide the value to be read by useContext.

Here’s an example:

const theme = {

light: {background: "#fff"},

dark: {background: "#000"}

}

// create context object with light theme as default

const ThemeContext = React.createContext(theme.light)

function App() {

return (

// have context provider up the tree (with its value set)

<ThemeContext.Provider value={theme.dark}>

<Body />

</ThemeContext.Provider>

)

}

function Body() {

//get theme value. make sure to pass context object

const theme = useContext(ThemeContext)

return (

{/* style element with theme from context*/}

<main style={{ background: theme.background, height: "50vh", color: "#fff" }}>

I am the main display styled by context!

</main>

)

}

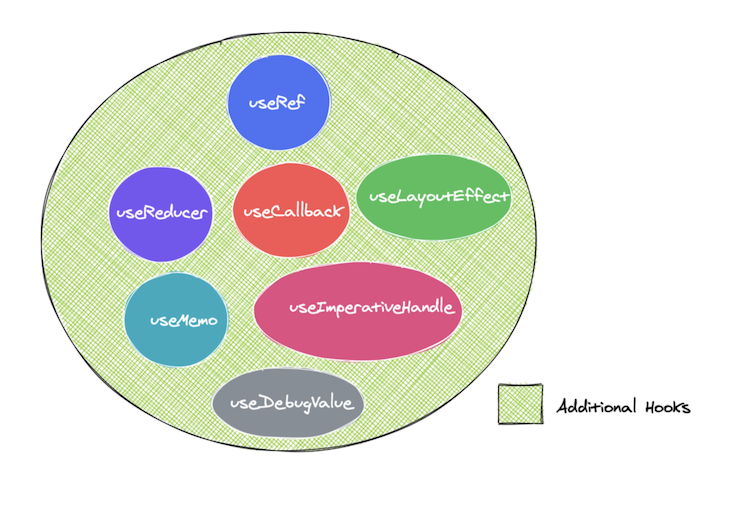

The following hooks are variants of the basic Hooks discussed in the sections above. If you’re new to Hooks, don’t bother learning these right now; they are only needed for specific edge cases.

useReduceruseReducer is an alternative to useState. Here’s how it’s used:

const [state, dispatch] = useReducer(reducer, initialArgument, init)

When invoked, useReducer returns an array that holds the current state value and a dispatch method. If you’re familiar with Redux, you already know how this dispatch works.

With useState, you invoke the state updater function to update state; with useReducer, you invoke the dispatch function and pass it an action, i.e., an object with at least a type property:

dispatch({type: 'increase'})

N.B., conventionally, an action object may also have a

payload, e.g.,{action: 'increase', payload: 10}.

While it’s not absolutely necessary to pass an action object that follows this pattern, it’s a very common pattern popularized by Redux.

useReducerWhen you have complex state logic that utilizes multiple sub-values, or when a state depends on the previous one, you should favor the use of useReducer over useState.

Like the setState updater function returned from calling useState, the dispatch method identity remains the same, so it can be passed down to child components instead of callbacks to update the state value held within useReducer.

reducer functionuseReducer accepts three arguments. The first, reducer, is a function of type (state, action) => newState. The reducer function takes in the current state and an action object and returns a new state value.

This takes some time to get used to unless you’re already familiar with the concepts of reducers.

Basically, whenever you attempt to update state managed via useReducer, i.e by calling dispatch, the current state value and the action argument passed to dispatch are passed on to the reducer.

//receives current state and dispatched action

const reducer = (state, action) => {

}

It’s your responsibility to then return the new state value from the reducer.

const reducer = (state, action) => {

// return new state value

return state * 10

}

A more common approach is to check the type of action being dispatched and act on that.

const reducer = (state, action) => {

// check action type

switch (action.type) {

case "increase":

//return new state

return state * 10;

default:

return state;

}

}

If you don’t pass the third argument to useReducer, the second argument to useReducer will be taken as the initialState for the Hook.

// two arguments useReducer(reducer, initialState) // three arguments useReducer(reducer, initialArgument, init) // I explain what the init function is in the "Lazy initialization" section below

Consider the example below:

const [state, dispatch] = useReducer(reducer, 10) // initial state will be 10

If you’re familiar with Redux, it’s worth mentioning that the state = initialState convention doesn’t work the same way with useReducer.

// where 10 represents the initial state

// doesn't work the same with useReducer

const reducer = (state = 10, action) {

}

The initialState sometimes needs to depend on props, and so is specified from the Hook call instead.

useReducer(state, 10) // where 10 represents the initial state

If you really want the redux style invocation, do this: useReducer(reducer, undefined, reducer). This is possible, but not encouraged.

The following is the growing button example from the useState Hook section refactored to use the useReducer Hook.

const reducer = (state, action) => {

switch (action.type) {

case "increase":

return state + 10;

default:

return state;

}

};

export default function App() {

const [width, dispatch] = useReducer(reducer, 50);

// you update state by calling dispatch

const increaseWidth = () => dispatch({ type: "increase" });

return (

<button style={{ width }} onClick={increaseWidth}>

I grow

</button>

);

}

You can also create the initial state lazily. To do this, pass a third argument to useReducer: the init function.

const [state, dispatch] = useReducer(reducer, initialArgument, init)

If you pass an init function, the initial state will be set to init(initialState), i.e., the function will be invoked with the second argument, initialArgument.

This lets you extract the logic for calculating the initial state outside the reducer, and this is maybe handy for resetting the state later in response to an action.

function init(someInitialValue) {

return { state: someInitialValue }

}

function reducer(state, action) {

switch(action.type) {

//reset by calling init function

case 'reset':

// an action object typically has a "type" and a "payload"

return init(action.payload)

}

}

...

const initialValue = 10;

const [state, dispatch] = useReducer(reducer, initialValue, init)

If you try to update state with the same value as the current state, React won’t render the component children or fire effects, e.g., useEffect callbacks. React compares previous and current state via the Object.is comparison algorithm.

It’s important to note that in some cases, React may still render the specific component whose state was updated. That’s OK because React will not go deeper into the tree, i.e., render the component’s children.

If expensive calculations are done within the body of your functional component, consider optimizing these with useMemo.

useCallbackThe basic signature for useCallback looks like this:

const memoizedCallback = useCallback(callback, arrayDependency)

useCallback takes a callback argument and an array dependency list and returns a memoized callback.

The memoized callback returned by useCallback is guaranteed to have the same reference. It’s especially useful when passing callbacks to child components that depend on referential checks to prevent needless re-renders.

The array dependency is equally important. useCallback will recompute the memoized callback if any of the array dependency changes. This is important if you make use of values within the component scope in the callback and need to keep the values up to date when the callback is invoked.

N.B., be sure to include all referenced variables within the callback in the array dependency. You should also take advantage of the official ESLint plugin to help with checking that your array dependency is correct and providing a fix.

Consider the following example:

const App = () => {

const handleCallback = () => {

// do something important

}

return <ExpensiveComponent callback={handleCallback}/>

}

const ExpensiveComponent = React.memo(({props}) => {

// expensive stuff

})

Even though ExpensiveComponent is memoized via React.memo, it will still be re-rendered anytime App is re-rendered because the reference to the prop callback will change.

To keep the reference to callback the same, we can use the useCallback Hook:

const App = () => {

// use the useCallback hook

const handleCallback = useCallback(() => {

// do something important

})

return <ExpensiveComponent callback={handleCallback}/>

}

The above solution is incomplete. Without passing an array dependency, useCallback will recompute the returned memoized callback on every render. That’s not ideal. Let’s fix that:

const App = () => {

const handleCallback = useCallback(() => {

// do something important

}, []) // see array dependency

return <ExpensiveComponent callback={handleCallback}/>

}

Passing an empty array dependency means the memoized callback is only computed once: on mount.

Let’s assume that the callback required access to some props from the App component:

const App = ({props1, props2}) => {

const handleCallback = useCallback(() => {

// do something important

return props1 + props2

}, [props1, props2]) // see array dependency

return <ExpensiveComponent callback={handleCallback}/>

}

In such a case, it is important to have props1 and props2 as part of the array dependency list. Except you have good reasons not to do so, you should always do this.

Assuming props1 and props2 are JavaScript values compared by value and not reference, e.g., strings or Booleans, the example above is straightforward and easy to comprehend.

What if props1 refers to a function?

const App = ({props1, props2}) => {

const handleCallback = useCallback(() => {

return props1(props2)

}, [props1, props2]) // see array dependency

return <ExpensiveComponent callback={handleCallback}/>

}

By placing props1 the function as an array dependency, you’ve got to be certain its reference doesn’t change all the time, i.e., on all re-renders. If it does, then it defies the purpose of using useCallback because the memoized callback returned by useCallback will change every time props1 changes.

There are different ways to deal with this, but in a nutshell, you may want to avoid passing such changing callbacks down to child components. props1 could also be memoized using useCallback or avoided altogether.

useMemoWhile useCallback returns a memoized callback, useMemo returns a memoized value. This is a bit of an ambiguous statement since a callback could also be a value, but essentially, useCallback(fn, deps) is equivalent to useMemo(() => fn, deps).

If that’s confusing, consider the basic signature for useMemo:

const memoizedValue = useMemo(callback, arrayDependency);

This looks very similar to the signature for useCallback. The difference here is that the callback for useMemo is a “create” function; it is invoked and a value is returned. The returned value is what’s memoized by useMemo.

Now you may take a second look at the statement made earlier:

useCallback(fn, deps) === useMemo(() => fn, deps)

The statement above is true because useMemo invokes the “create” function () => fn. Remember that arrow functions implicitly return. In this case, invoking the “create” function returns fn . Making it equivalent to the useCallback alternative.

Use useCallback to memoize callbacks and useMemo to memoize values; typically the result of an expensive operation you don’t want to be recomputed on every render:

const memoizedValue = useMemo(() => computeExpensiveValue(a, b), [a,b]);

useMemo can be used as an optimization to avoid expensive calculations on every render. While this is encouraged, it isn’t a semantic guarantee. In the future, React may choose to ignore previously memoized values and recompute them on next render, e.g., to free memory for offscreen components.

The rule of thumb is that your code should work without useMemo, then add useMemo for performance optimization. Note that the array dependency for useMemoworks the same as in useCallback:

const App = () => {

useMemo(() => someExpensiveCalculation())

return null

}

Without an array dependency, as seen above, someExpensiveCalculation will still be run on every re-render.

const App = () => {

// see array below

useMemo(() => someExpensiveCalculation(), [])

return null

}

With an empty array, it only runs on mount.

N.B., be sure to include all referenced variables within the callback in the array dependency. You should also take advantage of the official ESLint plugin to help with checking that your array dependency is correct and providing a fix.

useRefThe basic signature for the useRef Hook looks like this:

const refObject = useRef(initialValue)

useRef returns a mutable object whose value is set as: {current: initialValue}.

The difference between using useRef and manually setting an object value directly within your component, e.g., const myObject = {current: initialValue}, is that the ref object remains the same all through the lifetime of the component, i.e., across re-renders.

const App = () => {

const refObject = useRef("value")

//refObject will always be {current: "value"} every time App is re-rendered.

}

To update the value stored in the ref object, you go ahead and mutate the current property as follows:

const App = () => {

const refObject = useRef("value")

//update ref

refObject.current = "new value"

//refObject will always be {current: "new value"}

}

The returned object from invoking useRef will persist for the full lifetime of the component regardless of re-renders.

A common use case for useRef is to store child DOM nodes:

function TextInputWithFocusButton() {

//1. create a ref object with initialValue of null

const inputEl = useRef(null);

const onButtonClick = () => {

// 4. `current` points to the mounted text input element

// 5. Invoke the imperative focus method from the current property

inputEl.current.focus();

};

return (

<>

{/* 2. as soon as input is rendered, the element will be saved in the ref object, i.e., {current: *dom node*} */}

<input ref={inputEl} type="text" />

{/* 3. clicking the button invokes the onButtonClick handler above */}

<button onClick={onButtonClick}>Focus the input</button>

</>

);

}

The example above works because if you pass a ref object to React, e.g., <div ref={myRef} />, React will set its current property to the corresponding DOM node whenever that node changes, i.e., myRef = {current: *dom node*}.

useRef returns a plain JavaScript object, so it can be used for holding more than just DOM nodes — it can hold whatever value you want. This makes it the perfect choice for simulating instance-like variables in functional components:

const App = ({prop1}) => {

// save props1 in ref object on render

const initialProp1 = useRef(prop1)

useEffect(() => {

// see values logged here

console.log({

initialProp1: initialProp1.current,

prop1

})

}, [prop1])

}

In the example above, we log initialProp1 and prop1 via useEffect. This will be logged on mount and every time prop1 changes.

Since initialProp1 is prop1 saved on initial render, it never changes. It’ll always be the initial value of props1. Here’s what we mean.

If the first value of props1 passed to App were 2, i.e., <App prop1={2} />, the following will be logged on mount:

{

initialProp1: 2,

prop1: 2,

}

If prop1 passed to App were changed from 2 to 5 — say, owing to a state update — the following will be logged:

{

initialProp1: 2, // note how this remains the same

prop1: 5,

}

initialProp1 remains the same through the lifetime of the component because it is saved in the ref object. The only way to update this value is by mutating the current property of the ref object: initialProp1.current = *new value*.

With this, you can go ahead and create instance-like variables that don’t change within your functional component.

Remember, the only difference between useRef and creating a {current: ...} object yourself is that useRef will give you the same ref object on every render.

There’s one more thing to note. useRef doesn’t notify you when its content changes, i.e., mutating the current property doesn’t cause a re-render. For cases such as performing a state update after React sets the current property to a DOM node, make use of a callback ref as follows:

function UpdateStateOnSetRef() {

// set up local state to be updated when ref object is updated

const [height, setHeight] = useState(0);

// create an optimised callback via useCallback

const measuredRef = useCallback(node => {

// callback passed to "ref" will receive the DOM node as an argument

if (node !== null) {

// check that node isn't empty before calling state

setHeight(node.getBoundingClientRect().height);

}

}, []);

return (

<>

{/* pass callback to the DOM ref */}

<h1 ref={measuredRef}>Hello, world</h1>

<h2>The above header is {Math.round(height)}px tall</h2>

</>

);

}

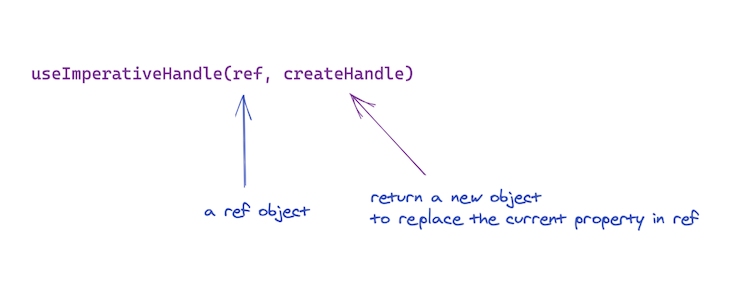

useImperativeHandleThe basic signature for the useImperativeHandle Hook is:

useImperativeHandle(ref, createHandle, [arrayDependency])

useImperativeHandle takes a ref object and a createHandle function whose return value “replaces” the stored value in the ref object.

Note that useImperativeHandle should be used with forwardRef.

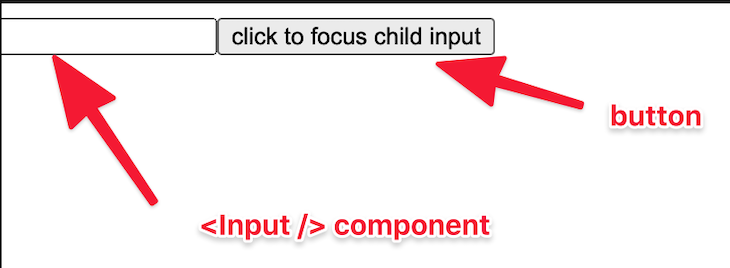

Consider the following example:

The goal of the application is to focus the input when the button element is clicked. A pretty simple problem.

const App = () => {

const inputRef = useRef(null);

const handleClick = () => {

inputRef.current.focus();

};

return (

<>

<Input ref={inputRef} />

<button onClick={handleClick}>click to focus child input</button>

</>

);

}

The solution above is correct. We create a ref object and pass that to the Input component. To forward the ref object to the Input child component, we use forwardRef as follows:

const Input = forwardRef((props, ref) => {

return <input ref={inputRef} {...props} />;

});

This is great, it works as expected.

However, in this solution, the parent component App has full access to the input element, i.e., the inputRef declared in App holds the full DOM node for the child input element.

What if you didn’t want this? What if you want to hide the DOM node from the parent and just expose a focus function, which is basically all the parent needs?

That’s where useImperativeHandle comes in.

Within the Input component, we can go ahead and use the useImperativeHandle Hook as follows:

const Input = forwardRef((props, ref) => {

// create internal ref object to hold actual input DOM node

const inputRef = useRef();

// pass ref from parent to useImperativeHandle and replace its value with the createHandle function

useImperativeHandle(ref, () => ({

focus: () => {

inputRef.current.focus();

}

}));

// pass internal ref to input to hold DOM node

return <input ref={inputRef} {...props} />;

});

Consider the useImperativeHandle invocation:

useImperativeHandle(ref, () => ({

focus: () => {

inputRef.current.focus();

}

}));

The function argument returns an object. This object return value is set as the current property for the ref passed in from the parent.

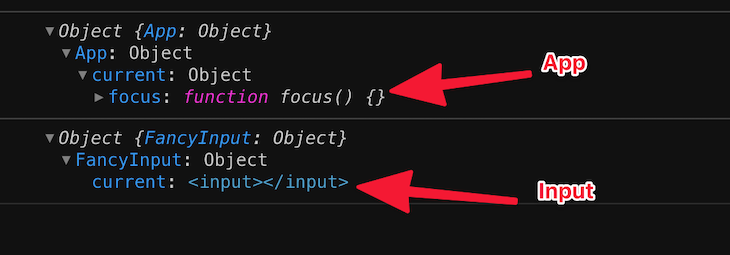

Instead of the parent having full access to the entire DOM node, the inputRef in App will now hold {current: focus: ..}, where focus represents the function we defined within useImperativeHandle.

If you went ahead and logged the ref objects in the parent component App and child component Input, this becomes even more apparent:

Now you know how useImperativeHandle works! It’s a way to customize the instance value that is exposed to parent components when using ref — a very specific use case.

If you need control over the re-computation of the value returned from the function argument to useImperativeHandle, be sure to take advantage of the array dependency list.

useLayoutEffectThe signature for useLayoutEffect is identical to useEffect; the difference is the time of execution.

Your useLayoutEffect callback/effects will be fired synchronously after all DOM mutations, i.e., before the browser has a chance to paint.

It is recommended that you use useEffect when possible to avoid blocking visual updates. However, there are legitimate use cases for useLayoutEffect, e.g., to read layout from the DOM and synchronously re-render.

If you are migrating code from a class component, useLayoutEffect fires in the same phase as componentDidMount and componentDidUpdate, but start with useEffect first, and only try useLayoutEffect if that causes a problem. Don’t block visual updates except when you’re absolutely sure you need to.

It’s also worth mentioning that with server-side rendering, neither useEffect nor useLayoutEffect are run until JavaScript is downloaded on the client.

You’ll get a warning with server-rendered components containing useLayoutEffect. To resolve this, you can either move the code to useEffect, i.e., to be fired after first render (and paint), or delay showing the component until after the client renders.

To exclude a component that needs layout effects from the server-rendered HTML, render it conditionally with showChild && <Child /> and defer showing it with useEffect(() => { setShowChild(true); }, []). This way, the UI doesn’t appear broken before hydration.

useDebugValueThe basic signature for useDebugValue is as follows:

useDebugValue(value)

useDebugValue can be used to display a label for custom Hooks in React DevTools.

Consider the following basic custom Hook:

const useAwake = () => {

const [state, setState] = useState(false);

const toggleState = () => setState((v) => !v);

return [state, toggleState];

};

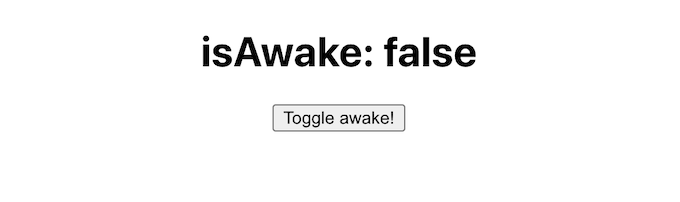

A glorified toggle Hook. Let’s go ahead and use this custom Hook:

export default function App() {

const [isAwake, toggleAwake] = useAwake();

return (

<div className="App">

<h1>isAwake: {isAwake.toString()} </h1>

<button onClick={toggleAwake}>Toggle awake!</button>

</div>

);

}

Here’s the result:

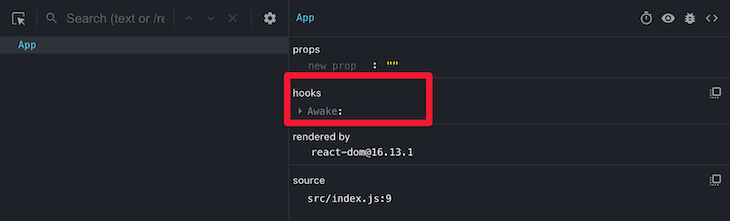

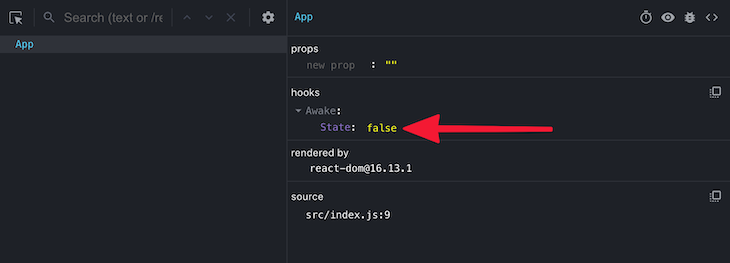

Consider how the React DevTools displays this:

Every custom Hook within your app is displayed in the DevTools. You can click on each Hook to view its internal state:

If you want to display a custom “label” in the DevTools, we can use the useDebugValue Hook as follows:

const useAwake = () => {

const [state, setState] = useState(false);

// look here

useDebugValue(state ? "Awake" : "Not awake");

...

};

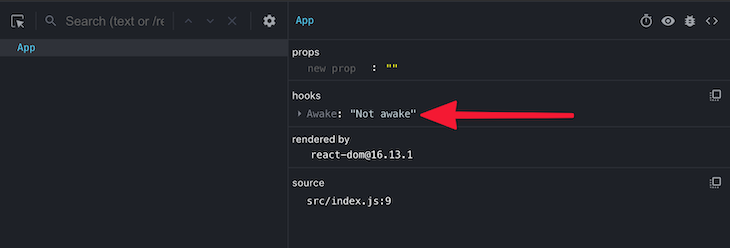

The custom label will now be displayed in the DevTools, as seen below:

N.B., don’t add debug values to every custom Hook. These are most valuable for custom Hooks that are part of shared libraries.

In some cases, formatting a value for display via useDebugValue might be an expensive operation. It’s also unnecessary to run this expensive operation unless a Hook is actually inspected. For such cases, you can pass a function to useDebugValue as a second argument.

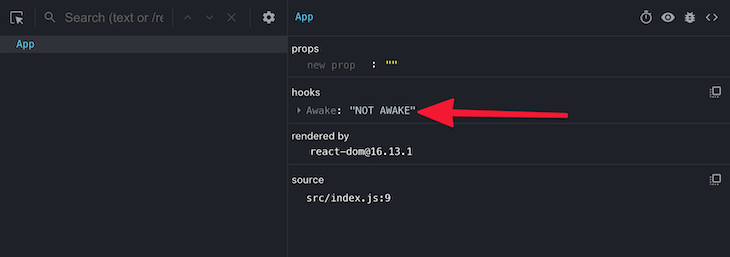

useDebugValue(state ? "Awake" : "Not awake", val => val.toUpperCase());

In the example above, we avoid calling val.toUpperCase unnecessarily as it’ll only be invoked if the Hook is inspected in the React DevTools.

Install LogRocket via npm or script tag. LogRocket.init() must be called client-side, not

server-side

$ npm i --save logrocket

// Code:

import LogRocket from 'logrocket';

LogRocket.init('app/id');

// Add to your HTML:

<script src="https://cdn.lr-ingest.com/LogRocket.min.js"></script>

<script>window.LogRocket && window.LogRocket.init('app/id');</script>

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

Discover how to use Gemini CLI, Google’s new open-source AI agent that brings Gemini directly to your terminal.

This article explores several proven patterns for writing safer, cleaner, and more readable code in React and TypeScript.

A breakdown of the wrapper and container CSS classes, how they’re used in real-world code, and when it makes sense to use one over the other.

This guide walks you through creating a web UI for an AI agent that browses, clicks, and extracts info from websites powered by Stagehand and Gemini.

One Reply to "React Reference Guide: Hooks API"

The effect callback is invoked after the browser layout and painting are carried out.