One of my favorite Dave Wascha talks, 20 years of product management in 25 minutes, discusses the dichotomy of paying attention to the competition and, at the same time, not doing so. He makes a point about copying what works but never forgetting about finding solutions for your own users’ problems.

But there is more to that than just it, right? Nothing in product works as a rule of thumb. Saying that you should pay attention to the competition and your users at the same time is close to saying nothing at all. When should you do each one? How? And more importantly, why?

Meta has been fighting a gruesome battle to stay on top of the social media food chain, and they have been doing remarkably well at it. Their uncontested leadership of both their Facebook and Instagram platforms has been severely challenged twice in the last 10 years — first by Snapchat and more recently by TikTok.

If you’re on both platforms, maybe you’ve noticed by now that Instagram (owned by Meta) has been playing a lot of catchup. Snapchat rolled out a “stories” feature, and Instagram did the exact same not very long after. With the rise in popularity of TikTok, Instagram now has a “reels” feature, mimicking the same infinite scrolling mechanism of TikTok’s feed of catered videos dependent on each user’s interests. Weird, right?

In this article, we’ll talk about TikTok vs. Instagram and the battle to stay ahead of the competition. Hopefully, we can learn a thing or two about product management in highly competitive environments.

When the two social platform contenders, Snapchat and TikTok, hit the market, both had stellar growth. Analysts were quick to deem Instagram and Facebook as dead because of these two new players, but twice already, they’ve been proven wrong.

According to Data.ai, Instagram was the most downloaded app in Q3 of 2022 and they had the third most active user base, behind only Facebook and WhatsApp (both are Meta’s businesses).

The reason why Meta systematically wins those battles is because they are master copycats. It’s not just about copying, it’s about knowing whom to copy and when. The product team inside Meta has a singular awareness of who they are, what their market looks like, what their users think, and, finally, who they should pick a fight with.

Again, Meta has three main platforms under their belt: Instagram, Facebook, and WhatsApp. For the sake of this case study, let’s put WhatsApp aside. One can hardly call it a “social network” and it’s the least historically-challenged platform of the three.

Before thinking about your competition, you must have a pristine understanding of what your strengths and weaknesses are, and in which context you find yourself. I’m not talking about features, but the actual strategy and vision of what your product can or cannot do.

Facebook was born in 2004. It has consolidated itself as the leader of a market that was the size of a pea compared to what it is now. The first alternative to question its authority was Instagram, which was quickly bought out by Facebook, aka Meta, in 2012.

Up until that moment, Facebook’s strategy was a pretty common one for big businesses: buy the challengers before they become too big to fight against. Google did that with YouTube (now the second biggest search engine in the world), Amazon acquired Zappos, Apple bought Beats — the list goes on.

Facebook intended to stick to that plan when Snapchat became a menace, but they received a cold, hard, “no thanks” from the founders. After denying Google as well, it was clear that Snapchat was in for the long run. Facebook had to shift strategies before it was too late.

Snapchat was born in 2011, Facebook tried to buy it in 2013, and Instagram launched stories in 2016, basically just copying that key feature of Snapchat. Looking at the history, one can clearly see the strategic shift from Facebook. The definitive evidence is that years later, when TikTok became a thing, Facebook skipped the buyout attempt entirely.

TikTok was launched in 2017 and Instagram released a reels component to mimic it in 2020. The TikTok vs. Instagram war began.

Now that we have some context, let’s dive into what matters: successful competition management.

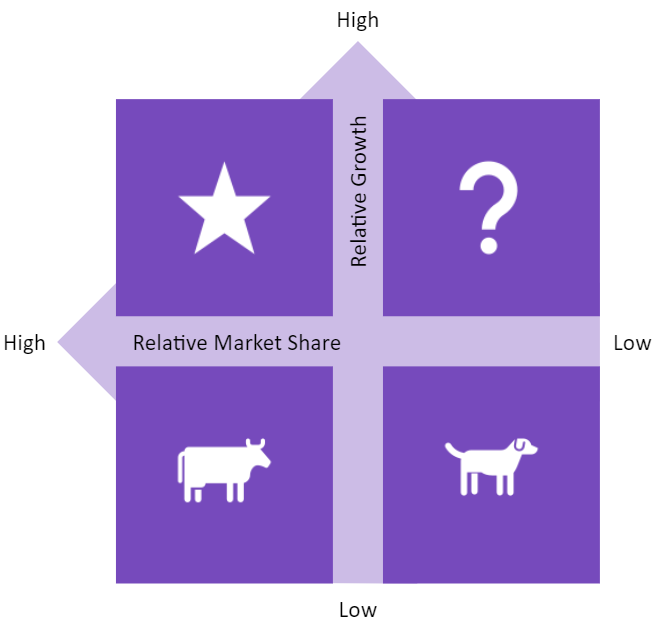

The backbone of my train of thought will be the BCG Matrix or “growth-share matrix.” This is a framework used to assess the market trends of different businesses, products, or features inside a market. Very versatile, this matrix can be used on all sorts of analyses — from internal platform adoption to macroeconomic planning.

The matrix has two axes: relative growth and relative market share. Those two axes cross each other at the center, creating four quadrants: stars, question marks, cash cows, and dogs. The image below illustrates what the matrix looks like:

Stars are assessed as an already big market share holder, but they still grow a lot. Think of Netflix before streaming became a commonplace strategy for content businesses.

Cash cows have a big market share, but they don’t grow that much. They are there to make money and losing the function would hurt the business badly. Think of Windows or Microsoft Office within Microsoft’s portfolio.

Question marks are normally newcomers inside the market. They have small market shares but accelerated growth. Almost all big tech companies we know today were once question marks.

Dogs are low growth, low share assessments. They might be dying, they might be looking for market fit, or they might be niche solutions. Either way, dogs often are irrelevant unless it’s you that fits on this quadrant.

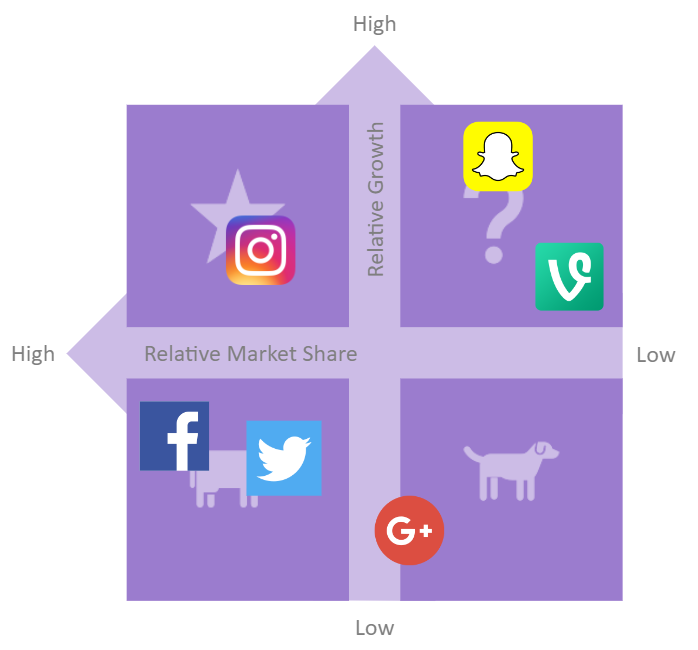

Back to our case study, 2012–2013 would look something like this, considering active users for social media:

This visual representation is far from a precise assessment, but for this article, it’s good enough to present the landscape of the market back in the early 2010s. Facebook was growing at a stable rate, Twitter was beginning to plateau, Instagram was still growing exponentially despite its size, and Google+ never became a real contender. There were two open questions: Snapchat and Vine.

It was pretty clear who should be observed. Either Snapchat or Vine had the opportunity to become stars if left unchecked for too long. If someone else was to become a star other than Instagram, that would most probably mean that Instagram would become a cash cow (which Facebook already was) or worse, a dog.

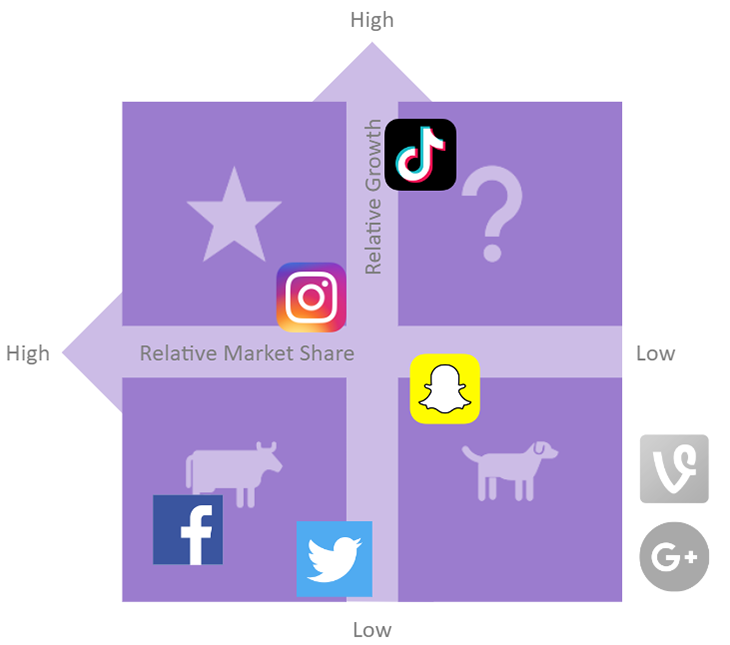

The 2020s have presented a similar challenge to Meta, but way more threatening. Despite having fewer players to deal with, TikTok was a much stronger opponent, dangerous from birth given its sharp growth. Even worse, Facebook is now far from the power player it once was, and as it loses market share, the more and more it starts to look like a dog:

Some things remain the same between the 2013s and the 2020s, though. Instagram is still a star (barely), Facebook is still a reliable source of income for Meta (mainly due to advertising), and TikTok is still an open question in the likes of what Snapchat once was. Some sources estimate that TikTok already has more users than Instagram.

Meta had their priorities straight, targeting both Snapchat and TikTok, but it’s more important to understand why these two were growing so much in the first place. After all, that’s essentially what separates a new player from becoming a star or a dog in the way that Vine did.

For a free product, price is not something to take into consideration. With the distribution channels in pretty much the same boat, it’s a matter of studying the only thing that can make a difference: features.

Comparing features is not always an easy job. More than the functionalities, you must compare perceived values against each other. Nobody buys iPhones over Androids because they have a better synergy between hardware and software. People do it because an iPhone delivers status and a familiar experience, while an Android phone is just a phone.

Likewise, Facebook could not simply compare features and call it a day. They had to understand where their users’ hearts and minds belonged, and how to transform those perceived points of difference into points of parity.

I just dropped two pretty classic marketing concepts on your lap, so let me take a step back and explain those to you:

Having a user top of heart and top of mind are completely different things, but not exclusive ones.

Being top of mind means that your product or brand is the first thing that comes to mind when someone thinks of a category. Coke is the most famous example: when someone asks you to name a soft drink, your mind goes probably directly to Coke.

Being top of heart, on the other hand, is about being the favorite brand or product of your audience. You might not be the first thing that pops into your consumer’s heads, but they will choose you over anything else when presented with an option. People who drink Pepsi swear that it tastes better than Coke, even though blind tests have proven over and over again that they are almost indistinguishable from one another.

Being top of mind is important, but being top of heart is where power really lies. Top of mind is about awareness and trendiness — it comes and goes with your marketing budget. Blackberry was top of mind for some time before iPhones became a thing, and now people just think of the fruit.

Building top of heart is about delight and experiences. It’s about associating your product with personal experiences that are part of your consumer’s character. Maybe your holiday parties always had Coke. The first time the cool kid called you by name was because you had a new iPhone. The first video recording of your newborn was posted right to Instagram.

Hold that thought for later…

This is a simpler concept. A differentiation point is anything that presents your product or brand as different from another option. In the same way, a parity point is something you have in common with your competitors.

The most interesting characteristic of this concept is that pursuing the delivery of differentiation or parity points is completely context-dependent. There is no “right” or “wrong.”

If you are a consolidated player (such as Meta) and a new competitor pops out in the market (such as TikTok), you must pay attention to its differentiation points compared to you. What you can do later is:

If you’re a newcomer, on the other hand, you can’t rely on differentiation points alone. You must attend to some basic parity points of that market before you call yourself a competitor. In the TikTok example, it had to implement a follow feature, timelines, and “like” buttons to be considered a social network.

There is an interesting dichotomy between parity and differentiation in the sense that they are not set in stone. If a differentiation point becomes too popular, it’s transformed into a parity one by the rest of the market. If the market gives up on some parity except for one player, it is now a differentiation point.

Now that we’re familiar with the concepts, time to break down Meta’s logic:

Both Snapchat and TikTok brought something new to the game. They were not just photo albums like the first iterations of Instagram and Facebook were. They were live feeds, it was something in between YouTube and Twitter.

Snapchat’s differentiation was that every photo quickly expired, while TikTok brought in automatic discovery. More than the video features themselves, the value each delivered was vastly different from what Meta had to offer.

Snapchat created the concept of exclusivity for your feed — if you saw it, you were “in,” and if you didn’t, you were “out.” TikTok built up a similar concept, but it gave those creators reach. Now a man from Singapore could laugh at your silly Canadian video, even though both of you have no idea who the other person is.

Each of those differentiation points took the concept of “social network” away from the parity points that Meta knew and controlled. They had to step up their game if they were to use the only weapon they had: top of mind AND top of heart. Something that both contender networks had little to no of in most demographics.

Fighting a two-front war is almost a guarantee of loss. Luckily, Meta had a lot of time between one battle and the other. Snapchat was completely nullified as a threat in 2017. TikTok has (apparently) been put under control as of the end of 2022, despite it having more active users than Instagram already according to some sources.

The action plan here is quite straightforward: implement the same functionalities, advertise them, and let top of mind and top of heart do their job. The interesting thing here, and probably an important part of the strategy’s success, is why Instagram first?

The 1997 book, The Innovator’s Dilemma by Clayton M. Christensen, coined an interesting concept that explains why big companies die from time to time because of smaller businesses. The basic premise is that innovation is an S-curve, in the sense that early iterations of a product generate way more adoption than late-stage iterations.

Newer businesses that build on top of the parities lead previous players to deliver stronger differentiations, therefore gaining users more effectively and transforming the business to the point of old players not being able to compete anymore.

The point is that innovation can’t be controlled by a single player, and those that come after will innovate in ways that previous players can’t even fathom. Since legacy user bases are large and well consolidated, they won’t accept receiving a worse service just because it’s new. Therefore, to innovate constantly, a business should accept hurting its cash cow, which leads to a decline the same way. Hence the dilemma.

Snapchat and TikTok were nothing more than that: new players threatening a well-consolidated market leader. Following the recommendations of Christensen, Facebook had a faster, more nimble business that could pivot with greater ease without compromising its main cash cow: the one and only Instagram. The TikTok vs. Instagram battle has mellowed out.

So that’s the plan: leverage the more flexible part of the business (Instagram) to match new features with an innovative value delivery from Snapchat or TikTok. Counting on both the top of mind and (most importantly) top of heart that Meta’s brands so tactfully built, users should flock back to their platform after delivery.

It was a hit with Snapchat and apparently, it’s working somehow against TikTok. With TikTok numbers still strong and Snapchat making a comeback, only time will tell if Zuckerberg just postponed the inevitable or if the crown indeed belongs to him.

This case study is a gross reductionism of the real situation. There are a plethora of other factors that influence those numbers: trade wars, the Kardashians, Zuckerberg and the Metaverse, Gen Z’s purchase behavior, and so forth.

The whole point is to illustrate how apparently disconnected concepts work with each other. The innovator’s dilemma exists because question marks in the market build differentiations on top of established parities. Some cash cows can’t pivot easily and are all doomed to die, while others ascend to starhood. You can keep it inside the family or let another one snag it away from you, but nothing is set in stone.

Be it a star, a cow, a dog, or a question mark, business is cruel to all, and you only have product sense to fight with.

Is Instagram’s New ‘Reels’ a Genuine Threat to TikTok? — Sambda Digital

Instagram Beats TikTok For Top App Among A Record 39 Billion Apps Installed Last Quarter — Forbes

TikTok User Statistics: Everything You Need To Know About TikTok Users — Search Logistics

LogRocket identifies friction points in the user experience so you can make informed decisions about product and design changes that must happen to hit your goals.

With LogRocket, you can understand the scope of the issues affecting your product and prioritize the changes that need to be made. LogRocket simplifies workflows by allowing Engineering, Product, UX, and Design teams to work from the same data as you, eliminating any confusion about what needs to be done.

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

AI governance is now a product feature. Learn how to embed trust, transparency, and compliance into your build cycles.

Rachel Bentley shares the importance of companies remaining transparent about reviews and where they’re sourced from to foster user trust.

Michal Ochnicki talks about the importance of ensuring that the ecommerce side of a business is complementary to the whole organization.

Christina Valls shares how her teams have transformed digital experiences at Cedars-Sinai, including building a digital scheduling platform.