To use a method on a given array, we type [].methodName. They are all defined in the Array.prototype object. Here, however, we won’t be using these; instead, we’ll define our own versions starting from the simple method and build up on top of these until we get them all.

There is no better way to learn than to take things apart and put them back together. Note that when working on our implementations, we won’t be overriding existing methods, since that is never a good idea (some packages we import may be dependent on it). Also, this is going to allow us to compare how our versions fare against the original methods.

So instead of writing this:

Array.prototype.map = function map() {

// implementation

};

We are going to do this:

function map(array) {

// takes an array as the first argument

// implementation

}

We could also implement our methods by using the class keyword and extending the Array constructor like so:

class OwnArray extends Array {

public constructor(...args) {

super(...args);

}

public map() {

// implementation

return this;

}

}

The only difference would be that instead of using the array argument, we would be using the this keyword.

However, I felt this would bring about unnecessary confusion, so we are going to stick with the first approach.

With that out of the way, let’s kick it off by implementing the easiest one — the forEach method!

The Array.prototype.forEach method takes a callback function and executes it for each item in the array without mutating the array in any way.

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5].forEach(value => console.log(value));

function forEach(array, callback) {

const { length } = array;

for (let index = 0; index < length; index += 1) {

const value = array[index];

callback(value, index, array);

}

}

We iterate over the array and execute the callback for each element. The important thing to note here is that the method doesn’t return anything — so, in a way, it returns undefined.

What’s great about working with array methods is the possibility of chaining operations together. Consider the following code:

function getTodosWithCategory(todos, category) {

return todos

.filter(todo => todo.category === category)

.map(todo => normalizeTodo(todo));

}

This way, we don’t have to save the result of map to a variable and generally have better-looking code as a result.

Unfortunately, forEach doesn’t return the input array! This means we can’t to do the following:

// Won't work!

function getTodosWithCategory(todos, category) {

return todos

.filter(todo => todo.category === category)

.forEach((value) => console.log(value))

.map(todo => normalizeTodo(todo));

}

The console.log here, of course, is useless.

I have written a simple utility function that will better explain what each method does: what it takes as input, what it returns, and whether or not it mutates the array.

function logOperation(operationName, array, callback) {

const input = [...array];

const result = callback(array);

console.log({

operation: operationName,

arrayBefore: input,

arrayAfter: array,

mutates: mutatesArray(input, array), // shallow check

result,

});

}

Here’s the utility function run for our implementation of forEach:

logOperation('forEach', [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], array => forEach(array, value => console.log(value)));

{

operation: 'forEach',

arrayBefore: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

arrayAfter: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

mutates: false,

result: undefined

}

Due to the fact that we implement the methods as functions, we have to use the following syntax: forEach(array, ...) instead of array.forEach(...).

Note: I have also created test cases for every method to be sure they work as expected — you can find them in the repository.

One of the most commonly used methods is Array.prototype.map. It lets us create a new array by converting the existing values into new ones.

[1, 2, 3].map(number => number * 5); // -> [5, 10, 15]

function map(array, callback) {

const result = [];

const { length } = array;

for (let index = 0; index < length; index += 1) {

const value = array[index];

result[index] = callback(value, index, array);

}

return result;

}

The callback provided to the method takes the old value as an argument and returns a new value, which is then saved under the same index in the new array, here called result.

It is important to note here that we return a new array; we don’t modify the old one. This is an important distinction to make due to arrays and objects being passed as references here. If you are confused by the whole references versus values thing, here’s a great read.

logOperation('map', [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], array => map(array, value => value + 5));

{

operation: 'map',

input: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

output: [ 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 ],

mutates: false

}

Another very useful method is Array.prototype.filter. As the name suggests, it filters out the values for which the callback returned is false. Each value is saved in a new array that is later returned.

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5].filter(number => number >= 3); // -> [3, 4, 5]

function filter(array, callback) {

const result = [];

const { length } = array;

for (let index = 0; index < length; index += 1) {

const value = array[index];

if (callback(value, index, array)) {

push(result, value);

}

}

return result;

}

We take each value and check whether the provided callback has returned true or false and either append the value to the newly created array or discard it, appropriately.

Note that here we use the push method on the result array instead of saving the value at the same index it was placed in the input array. This way, result won’t have empty slots because of the discarded values.

logOperation('filter', [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], array => filter(array, value => value >= 2));

{

operation: 'filter',

input: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

output: [ 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

mutates: false

}

The reduce method is, admittedly, one of the more complicated methods. The extensiveness of its use, however, cannot be overstated, and so it is crucial to get a good grasp on how it works. It takes an array and spits out a single value. In a sense, it reduces the array down to that very value.

How that value is computed, exactly, is what needs to be specified in the callback. Let’s consider an example — the simplest use of reduce, i.e., summing an array of numbers:

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10].reduce((sum, number) => {

return sum + number;

}, 0) // -> 55

Note how the callback here takes two arguments: sum and number. The first one is always the result returned by the previous iteration, and the second one is the element of the array we’re currently considering in the loop.

And so here, as we iterate over the array, sum is going to contain the sum of numbers up to the current index of the loop since with each iteration we just add to it the current value of the array.

function reduce(array, callback, initValue) {

const { length } = array;

let acc = initValue;

let startAtIndex = 0;

if (initValue === undefined) {

acc = array[0];

startAtIndex = 1;

}

for (let index = startAtIndex; index < length; index += 1) {

const value = array[index];

acc = callback(acc, value, index, array);

}

return acc;

}

We create two variables, acc and startAtIndex, and initialize them with their default values, which are the argument initValue and 0, respectively.

Then, we check whether or not initValue is undefined. If it is, we have to set as the initial value the first value of the array and, so as not to count the initial element twice, set the startAtIndex to 1.

Each iteration, the reduce method saves the result of the callback in the accumulator (acc), which is then available in the next iteration. For the first iteration, the accumulator is set to either the initValue or array[0].

logOperation('reduce', [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], array => reduce(array, (sum, number) => sum + number, 0));

{

operation: 'reduce',

arrayBefore: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

arrayAfter: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

mutates: false,

result: 15

}

What operation on arrays can be more common than searching for some specific value? Here are a few methods to help us with this.

As the name suggests, findIndex helps us find the index of a given value inside the array.

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7].findIndex(value => value === 5); // 4

The method executes the provided callback for each item in the array until the callback returns true. The method then returns the current index. Should no value be found, -1 is returned.

function findIndex(array, callback) {

const { length } = array;

for (let index = 0; index < length; index += 1) {

const value = array[index];

if (callback(value, index, array)) {

return index;

}

}

return -1;

}

logOperation('findIndex', [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], array => findIndex(array, number => number === 3));

{

operation: 'findIndex',

arrayBefore: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

arrayAfter: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

mutates: false,

result: 2

}

find only differs from findIndex in that it returns the actual value instead of its index. In our implementation, we can reuse the already-implemented findIndex.

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7].findIndex(value => value === 5); // 5

function find(array, callback) {

const index = findIndex(array, callback);

if (index === -1) {

return undefined;

}

return array[index];

}

logOperation('find', [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], array => find(array, number => number === 3));

{

operation: 'find',

arrayBefore: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

arrayAfter: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

mutates: false,

result: 3

}

indexOf is another method for getting an index of a given value. This time, however, we pass the actual value as an argument instead of a function. Again, to simplify the implementation, we can use the previously implemented findIndex!

[3, 2, 3].indexOf(3); // -> 0

function indexOf(array, searchedValue) {

return findIndex(array, value => value === searchedValue);

}

We provide an appropriate callback to findIndex, based on the value we are searching for.

logOperation('indexOf', [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], array => indexOf(array, 3));

{

operation: 'indexOf',

arrayBefore: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

arrayAfter: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

mutates: false,

result: 2

}

lastIndexOf works the same way as indexOf, only it starts at the end of an array. We also (like indexOf) pass the value we are looking for as an argument instead of a callback.

[3, 2, 3].lastIndexOf(3); // -> 2

function lastIndexOf(array, searchedValue) {

for (let index = array.length - 1; index > -1; index -= 1) {

const value = array[index];

if (value === searchedValue) {

return index;

}

}

return -1;

}

We do the same thing we did for findIndex, but instead of executing a callback, we compare value and searchedValue. Should the comparison yield true, we return the index; if we don’t find the value, we return -1.

logOperation('lastIndexOf', [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 3], array => lastIndexOf(array, 3));

{

operation: 'lastIndexOf',

arrayBefore: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 3 ],

arrayAfter: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 3 ],

mutates: false,

result: 5

}

The every method comes in handy when we want to check whether all elements of an array satisfy a given condition.

[1, 2, 3].every(value => Number.isInteger(value)); // -> true

You can think of the every method as an array equivalent of the logical AND.

function every(array, callback) {

const { length } = array;

for (let index = 0; index < length; index += 1) {

const value = array[index];

if (!callback(value, index, array)) {

return false;

}

}

return true;

}

We execute the callback for each value. If false is returned at any point, we exit the loop and the whole method returns false. If the loop terminates without setting off the if statement (all elements yield true), the method returns true.

logOperation('every', [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], array => every(array, number => Number.isInteger(number)));

{

operation: 'every',

arrayBefore: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

arrayAfter: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

mutates: false,

result: true

}

And now for the complete opposite of every: some. Even if only one execution of the callback returns true, the function returns true. Analogically to the every method, you can think of the some method as an array equivalent of the logical OR.

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5].some(number => number === 5); // -> true

function some(array, callback) {

const { length } = array;

for (let index = 0; index < length; index += 1) {

const value = array[index];

if (callback(value, index, array)) {

return true;

}

}

return false;

}

We execute the callback for each value. If true is returned at any point we exit the loop and the whole method returns true. If the loop terminates without setting off the if statement (all elements yield false), the method returns false.

logOperation('some', [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], array => some(array, number => number === 5));

{

operation: 'some',

arrayBefore: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

arrayAfter: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

mutates: false,

result: true

}

The includes method works like the some method, but instead of a callback, we provide as an argument a value to compare elements to.

[1, 2, 3].includes(3); // -> true

function includes(array, searchedValue) {

return some(array, value => value === searchedValue);

}

logOperation('includes', [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], array => includes(array, 5));

{

operation: 'includes',

arrayBefore: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

arrayAfter: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

mutates: false,

result: true

}

Sometimes our arrays become two or three levels deep and we would like to flatten them, i.e., reduce the degree to which they are nested. For example, say we’d like to bring all values to the top level. To our aid come two new additions to the language: the flat and flatMap methods.

The flat method reduces the depth of the nesting by pulling the values out of the nested array.

[1, 2, 3, [4, 5, [6, 7, [8]]]].flat(1); // -> [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, [6, 7, [8]]]

Since the level we provided as an argument is 1, only the first level of arrays is flattened; the rest stay the same.

[1, 2, 3, [4, 5]].flat(1) // -> [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

function flat(array, depth = 0) {

if (depth < 1 || !Array.isArray(array)) {

return array;

}

return reduce(

array,

(result, current) => {

return concat(result, flat(current, depth - 1));

},

[],

);

}

First, we check whether or not the depth argument is lower than 1. If it is, it means there is nothing to flatten, and we should simply return the array.

Second, we check whether the array argument is actually of the type Array, because if it isn’t, then the notion of flattening is meaningless, so we simply return this argument instead.

We make use of the reduce function, which we have implemented before. We start with an empty array and then take each value of the array and flatten it.

Note that we call the flat function with (depth - 1). With each call, we decrement the depth argument as to not cause an infinite loop. Once the flattening is done, we append the returned value to the result array.

Note: the concat function is used here to merge two arrays together. The implementation of the function is explained below.

logOperation('flat', [1, 2, 3, [4, 5, [6]]], array => flat(array, 2));

{

operation: 'flat',

arrayBefore: [ 1, 2, 3, [ 4, 5, [Array] ] ],

arrayAfter: [ 1, 2, 3, [ 4, 5, [Array] ] ],

mutates: false,

result: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 ]

}

flatMap, as the name might suggest, is a combination of flat and map. First we map according to the callback and later flatten the result.

In the map method above, for each value, we returned precisely one value. This way, an array with three items still had three items after the mapping. With flatMap, inside the provided callback we can return an array, which is later flattened.

[1, 2, 3].flatMap(value => [value, value, value]); // [1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 3, 3, 3]

Each returned array gets flattened, and instead of getting an array with three arrays nested inside, we get one array with nine items.

function flatMap(array, callback) {

return flat(map(array, callback), 1);

}

As per the explanation above, we first use map and then flatten the resulting array of arrays by one level.

logOperation('flatMap', [1, 2, 3], array => flatMap(array, number => [number, number]));

{

operation: 'flatMap',

arrayBefore: [ 1, 2, 3 ],

arrayAfter: [ 1, 2, 3 ],

mutates: false,

result: [ 1, 1, 2, 2, 3, 3 ]

}

As you’ve just seen, the concat method is very useful for merging two or more arrays together. It is widely used because it doesn’t mutate the arrays; instead, it returns a new one that all the provided arrays are merged into.

[1, 2, 3].concat([4, 5], 6, [7, 8]) // -> [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]

function concat(array, ...values) {

const result = [...array];

const { length } = values;

for (let index = 0; index < length; index += 1) {

const value = values[index];

if (Array.isArray(value)) {

push(result, ...value);

} else {

push(result, value);

}

}

return result;

}

concat takes an array as the first argument and an unspecified number of values that could be arrays (but also could be anything else — say, primitive values) as the second argument.

At first, we create the result array by copying the provided array (using the spread operator, which spreads the provided array’s values into a new array). Then, as we iterate over the rest of the values provided, we check whether the value is an array or not. If it is, we use the push function to append its values to the result array.

If we did push(result, value), we would only append the array as one element. Instead, by using the spread operator push(result, ...value), we are appending all the values of the array to the result array. In a way, we flatten the array one level deep!

Otherwise, if the current value is not an array, we also push the value to the result array — this time, of course, without the spread operator.

logOperation('concat', [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], array => concat(array, 1, 2, [3, 4]));

{

arrayAfter: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

mutates: false,

result: [

1, 2, 3, 4, 5,

1, 2, 3, 4

]

}

The join method turns an array into a string, separating the values with a string of choice.

['Brian', 'Matt', 'Kate'].join(', ') // -> Brian, Matt, Kate

function join(array, joinWith) {

return reduce(

array,

(result, current, index) => {

if (index === 0) {

return current;

}

return `${result}${joinWith}${current}`;

},

'',

);

}

We make use of the reduce function: we pass to it the provided array and set the initial value to an empty string. Pretty straightforward so far.

The callback of reduce is where the magic happens: reduce iterates over the provided array and pieces together the resulting string, placing the desired separator (passed as joinWith) in between the values of the array.

The array[0] value requires some special treatment, since at that point result is still undefined (it’s an empty string), and we don’t want the separator (joinWith) in front of the first element, either.

logOperation('join', [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], array => join(array, ', '));

{

operation: 'join',

arrayBefore: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

arrayAfter: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

mutates: false,

result: '1, 2, 3, 4, 5'

}

The reverse method reverses the order of values in an array.

[1, 2, 3].reverse(); // -> [3, 2, 1]

function reverse(array) {

const result = [];

const lastIndex = array.length - 1;

for (let index = lastIndex; index > -1; index -= 1) {

const value = array[index];

result[lastIndex - index] = value;

}

return result;

}

The idea is simple: first, we define an empty array and save the last index of the one provided as an argument. We iterate over the provided array in reverse, saving each value at (lastIndex - index) place in the result array, which we return afterwards.

logOperation('reverse', [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], array => reverse(array));

{

operation: 'reverse',

arrayBefore: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

arrayAfter: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

mutates: false,

result: [ 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 ]

}

The shift method shifts the values of an array down by one index and by doing so removes the first value, which is then returned.

[1, 2, 3].shift(); // -> 1

function shift(array) {

const { length } = array;

const firstValue = array[0];

for (let index = 1; index < length; index += 1) {

const value = array[index];

array[index - 1] = value;

}

array.length = length - 1;

return firstValue;

}

We start by saving the provided array’s original length and its initial value (the one we’ll drop when we shift everything by one). We then iterate over the array and move each value down by one index. Once done, we update the length of the array and return the once-initial value.

logOperation('shift', [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], array => shift(array));

{

operation: 'shift',

arrayBefore: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

arrayAfter: [ 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

mutates: true,

result: 1

}

The unshift method adds one or more values to the beginning of an array and returns that array’s length.

[2, 3, 4].unshift(1); // -> [1, 2, 3, 4]

function unshift(array, ...values) {

const mergedArrays = concat(values, ...array);

const { length: mergedArraysLength } = mergedArrays;

for (let index = 0; index < mergedArraysLength; index += 1) {

const value = mergedArrays[index];

array[index] = value;

}

return array.length;

}

We start by concatenating values (individual values passed as arguments) and array (the array we want to unshift). It is important to note here that values come first; they are to be placed in front of the original array.

We then save the length of this new array and iterate over it, saving its values in the original array and overwriting what was there to begin with.

logOperation('unshift', [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], array => unshift(array, 0));

{

operation: 'unshift',

arrayBefore: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

arrayAfter: [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

mutates: true,

result: 6

}

Taking out a single value out of an array is simple: we just refer to it using its index. Sometimes, however, we would like to take a bigger slice of an array — say, three or four elements at once. That’s when the slice method comes in handy.

We specify the start and the end indices, and slice hands us the array cut from the original array at these indices. Note, however, that the end index argument is not inclusive; in the following example, only elements of indices 3, 4, and 5 make it to the resulting array.

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7].slice(3, 6); // -> [4, 5, 6]

function slice(array, startIndex = 0, endIndex = array.length) {

const result = [];

for (let index = startIndex; index < endIndex; index += 1) {

const value = array[index];

if (index < array.length) {

push(result, value);

}

}

return result;

}

We iterate over the array from startIndex to endIndex and push each value to the result. We also make use of the default parameters here so that the slice method simply creates a copy of the array when no arguments are passed. We achieve this by setting by default startIndex to 0 and endIndex to the array’s length.

Note: the if statement makes sure we push only if the value under a given index exists in the original array.

logOperation('slice', [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], array => slice(array, 1, 3));

{

operation: 'slice',

arrayBefore: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

arrayAfter: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

mutates: false,

result: [ 2, 3 ]

}

The splice method simultaneously removes a given number of values from the array and inserts in their place some other values. Although not obvious at first, we can add more values than we remove and vice versa.

First, we specify the starting index, then how many values we would like to remove, and the rest of the arguments are the values to be inserted.

const arr = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]; arr.splice(0, 2, 3, 4, 5); arr // -> [3, 4, 5, 3, 4, 5]

function splice<T>(array: T[], insertAtIndex: number, removeNumberOfElements: number, ...values: T[]) {

const firstPart = slice(array, 0, insertAtIndex);

const secondPart = slice(array, insertAtIndex + removeNumberOfElements);

const removedElements = slice(array, insertAtIndex, insertAtIndex + removeNumberOfElements);

const joinedParts = firstPart.concat(values, secondPart);

const { length: joinedPartsLength } = joinedParts;

for (let index = 0; index < joinedPartsLength; index += 1) {

array[index] = joinedParts[index];

}

array.length = joinedPartsLength;

return removedElements;

}

The idea is to make two cuts at insertAtIndex and insertAtIndex + removeNumberOfElements. This way, we slice the original array into three pieces. The first piece (firstPart) as well as the third one (here called secondPart) are what will make it into the resulting array.

It is between these two that we will insert the values we passed as arguments. We do this with the concat method. The remaining middle part is removedElements, which we return in the end.

logOperation('splice', [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], array => splice(array, 1, 3));

{

operation: 'splice',

arrayBefore: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

arrayAfter: [ 1, 5 ],

mutates: true,

result: [ 2, 3, 4 ]

}

The pop method removes the last value of an array and returns it.

[1, 2, 3].pop(); // -> 3

function pop(array) {

const value = array[array.length - 1];

array.length = array.length - 1;

return value;

}

First, we save the last value of the array in a variable. Then we simply reduce the array’s length by one, removing the last value as a result.

logOperation('pop', [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], array => pop(array));

{

operation: 'pop',

arrayBefore: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

arrayAfter: [ 1, 2, 3, 4 ],

mutates: true,

result: 5

}

The push method lets us append values at the end of an array.

[1, 2, 3, 4].push(5); // -> [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

export function push(array, ...values) {

const { length: arrayLength } = array;

const { length: valuesLength } = values;

for (let index = 0; index < valuesLength; index += 1) {

array[arrayLength + index] = values[index];

}

return array.length;

}

First we save the length of the original array and how many values to append there are in their respective variables. We then iterate over the provided values and append them to the original array.

We start the loop at index = 0, so each iteration we add to index the array’s length. This way we don’t overwrite any values in the original array, but actually append them.

logOperation('push', [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], array => push(array, 6, 7));

{

operation: 'push',

arrayBefore: [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ],

arrayAfter: [

1, 2, 3, 4,

5, 6, 7

],

mutates: true,

result: 7

}

The fill method is of use when we want to fill an empty array with, say, a placeholder value. If we wanted to create an array with a specified number of null elements, we could do it like this:

[...Array(5)].fill(null) // -> [null, null, null, null, null]

function fill(array, value, startIndex = 0, endIndex = array.length) {

for (let index = startIndex; index <= endIndex; index += 1) {

array[index] = value;

}

return array;

}

All the fill method really does is replace an array’s values in the specified range of indexes. If the range is not provided, the method replaces all the array’s values.

logOperation('fill', [...new Array(5)], array => fill(array, 0));

{

operation: 'fill',

arrayBefore: [ undefined, undefined, undefined, undefined, undefined ],

arrayAfter: [ 0, 0, 0, 0, 0 ],

mutates: true,

result: [ 0, 0, 0, 0, 0 ]

}

The last three methods are special in the way that they return generators. If you are not familiar with generators, feel free to skip them, as you likely won’t use them anytime soon.

The values method returns a generator that yields values of an array.

const valuesGenerator = values([1, 2, 3, 4, 5]);

valuesGenerator.next(); // { value: 1, done: false }

function values(array) {

const { length } = array;

function* createGenerator() {

for (let index = 0; index < length; index += 1) {

const value = array[index];

yield value;

}

}

return createGenerator();

}

First, we define the createGenerator function. In it, we iterate over the array and yield each value.

The keys method returns a generator that yields indices of an array.

const keysGenerator = keys([1, 2, 3, 4, 5]);

keysGenerator.next(); // { value: 0, done: false }

function keys(array) {

function* createGenerator() {

const { length } = array;

for (let index = 0; index < length; index += 1) {

yield index;

}

}

return createGenerator();

}

The implementation is exactly the same, but this time, we yield an index, not a value.

The entries method returns a generator that yields index-value pairs.

const entriesGenerator = entries([1, 2, 3, 4, 5]);

entriesGenerator.next(); // { value: [0, 1], done: false }

function entries(array) {

const { length } = array;

function* createGenerator() {

for (let index = 0; index < length; index += 1) {

const value = array[index];

yield [index, value];

}

}

return createGenerator();

}

Again, the same implementation, but now we combine both the index and the value and yield them in an array.

Using the array’s methods efficiently is the basis for becoming a good developer. Acquainting yourself with the intricacies of their inner workings is the best way I know to get good at it.

Note: I didn’t cover sort and toLocaleString here because their implementations are overly complicated and, for my taste, too convoluted for beginners. I also didn’t discuss copyWithin, since it’s never used — it’s absolutely useless.

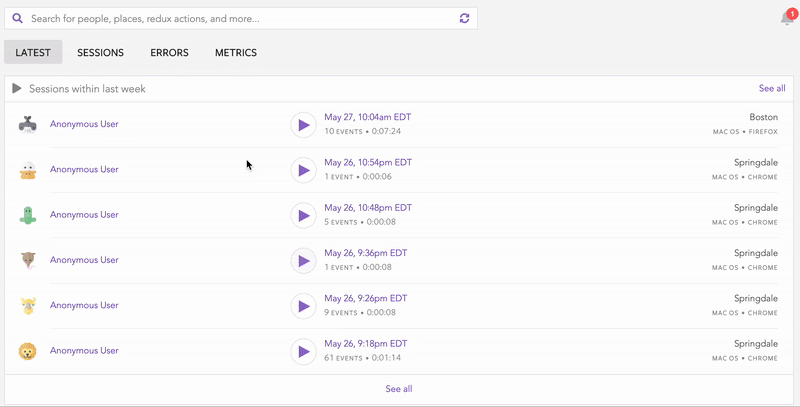

Debugging code is always a tedious task. But the more you understand your errors, the easier it is to fix them.

LogRocket allows you to understand these errors in new and unique ways. Our frontend monitoring solution tracks user engagement with your JavaScript frontends to give you the ability to see exactly what the user did that led to an error.

LogRocket records console logs, page load times, stack traces, slow network requests/responses with headers + bodies, browser metadata, and custom logs. Understanding the impact of your JavaScript code will never be easier!

Would you be interested in joining LogRocket's developer community?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

This guide explores how to use Anthropic’s Claude 4 models, including Opus 4 and Sonnet 4, to build AI-powered applications.

Which AI frontend dev tool reigns supreme in July 2025? Check out our power rankings and use our interactive comparison tool to find out.

Learn how OpenAPI can automate API client generation to save time, reduce bugs, and streamline how your frontend app talks to backend APIs.

Discover how the Interface Segregation Principle (ISP) keeps your code lean, modular, and maintainable using real-world analogies and practical examples.

2 Replies to "How to implement every JavaScript array method"

Hi! The .fill method has a tiny glitch – it should have

index <= endIndex

not '<' there.

Hi Tomek! Thanks for catching that, I will adjust the code accordingly.