GraphQL is the layer that provides data to the application, so it must serve the needs of the application. But sometimes GraphQL imposes its own way of working, and the application has to be adapted to work the GraphQL way.

This situation is most evident when using GraphQL with a CMS because CMSs are naturally opinionated and GraphQL might override their behavior. If we aren’t depending on a CMS and are instead building a site from scratch, then we should have full control of the site’s architecture and we may be willing to adapt it for GraphQL — and this conflict will not happen.

In this article, we will explore the way in which GraphQL imposes its own preconditions during data fetching, why it happens, and what options we have to work around it. We’ll be using WordPress as our example CMS.

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

Any application can have entities that contain children items of the same type. For instance, a menu contains items, which can have subitems, and those subitems can themselves contain subitems, and so on for several levels. Similarly, a comment can have responses that can themselves have responses.

Let’s see how to work with multi-level menus in GraphQL. Fetching the menu data in GraphQL involves querying the items inside the menu for all the different levels.

For instance, in this query, the menu has three levels and we use the fragment MenuItemProps to fetch the same fields (id, label, and url) for all of the menu items at all levels:

query GetMenu {

menu(id: 176) {

id

items {

...MenuItemProps

children {

...MenuItemProps

children {

...MenuItemProps

}

}

}

}

}

fragment MenuItemProps on MenuItem {

id

label

url

}

As it can be appreciated, the number of levels is reflected in the GraphQL query. Because the menu in the application has three levels, the GraphQL query has three levels of nesting.

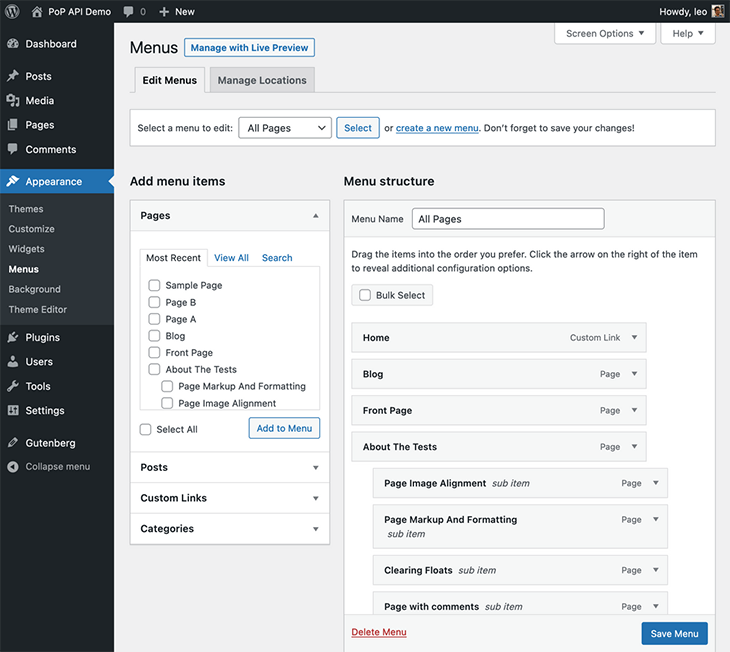

However, in WordPress, the creation of the menu is not decided in advance, by the theme or any plugin — instead, it is configured by the site’s admin via the Menus screen, and stored in the database:

This presents a problem: when a site admin adds an extra level to the menu via the user interface, this new level will not appear in the site if it is not also reflected in the GraphQL query. A developer must be engaged to modify the code — add the extra level to the GraphQL query, regenerate the theme’s .zip file, and reinstall it on the site. Only then will the new level show up in the query.

You might guess that by having to do all of this, the advantage of using a CMS is pretty much gone.

Indeed, WordPress is used not just by developers but also by non-developers, people who may not appreciate that their site’s theme would need to be updated in order to update a menu. This runs counterintuitive and contrary to the idea of a CMS, so GraphQL would be imposing its own way of working on its host WordPress.

Let’s look at three potential ways we can work around this issue.

A simple way of working around this issue is to initially structure the GraphQL query so that it fetches more levels than those needed, so there is room for a site admin to keep adding levels later on, without the need for a developer.

For instance, if the application needs three levels, the GraphQL query could nevertheless fetch data for six levels:

query GetMenu {

menu(id:176) {

id

items {

...MenuItemProps

children {

...MenuItemProps

children {

...MenuItemProps

children {

...MenuItemProps

children {

...MenuItemProps

children {

...MenuItemProps

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

fragment MenuItemProps on MenuItem {

id

label

url

}

This solution is not extremely elegant, but will work in most cases.

A better solution would be to tell GraphQL to keep iterating down the sublevels until there are no more of them, i.e., until the field children is null. When working with PHP, for instance, a function can call itself recursively, until the input is the basic element:

function filterFieldArgsWithNullValues(array $fieldArgs): array

{

return array_filter(

$fieldArgs,

function (mixed $elem): bool {

if (is_array($elem)) {

$filteredElem = $this->filterFieldArgsWithNullValues($elem);

return count($elem) === count($filteredElem);

}

return $elem !== null;

}

);

}

Porting this strategy to GraphQL would involve having a recursive fragment, where the fragment is once again applied to the children elements:

fragment MenuItemProps on MenuItem {

id

label

url

children {

...MenuItemProps

}

}

However, the GraphQL spec forbids fragments from being recursive, so this strategy is not possible.

Another solution would be to create a custom directive, @recursive, which recursively applies a fragment to a field’s connections and its sub-connections all the way down until reaching the leaf nodes in the graph:

query GetMenu {

menu(id:176) {

id

items @recursive(field: "children") {

...MenuItemProps

}

}

}

fragment MenuItemProps on MenuItem {

id

label

url

}

But this solution is also forbidden by the GraphQL spec because the shape of the response must match the shape of the query, and that would be compromised by the @recursive directive.

The last solution that comes to mind is to relax the use of nesting in the query, and create a single field, itemDataEntries, to produce a structured JSONObject with all of the menu data, including all levels and sublevels, as done in this query:

query GetMenu {

menu(id:176) {

id

itemDataEntries

}

}

The response to this query looks like this:

{

"data": {

"menu": {

"id": 176,

"itemDataEntries": [

{

"id": 735,

"objectID": "6",

"parentID": null,

"label": "About The Tests",

"url": "https://newapi.getpop.org/about/",

"children": [

{

"id": 1451,

"objectID": "1133",

"parentID": "735",

"label": "Page Image Alignment",

"url": "https://newapi.getpop.org/about/page-image-alignment/",

"children": []

},

{

"id": 1452,

"objectID": "1134",

"parentID": "735",

"label": "Page Markup And Formatting",

"url": "https://newapi.getpop.org/about/page-markup-and-formatting/",

"children": []

}

]

},

{

"id": 739,

"objectID": "174",

"parentID": null,

"label": "Level 1",

"url": "https://newapi.getpop.org/level-1/",

"children": [

{

"id": 740,

"objectID": "173",

"parentID": "739",

"label": "Level 2",

"url": "https://newapi.getpop.org/level-1/level-2/",

"children": [

{

"id": 741,

"objectID": "172",

"parentID": "740",

"label": "Level 3",

"url": "https://newapi.getpop.org/level-1/level-2/level-3/",

"children": []

},

{

"id": 1453,

"objectID": "747",

"parentID": "740",

"label": "Level 3a",

"url": "https://newapi.getpop.org/level-1/level-2/level-3a/",

"children": []

},

{

"id": 1454,

"objectID": "748",

"parentID": "740",

"label": "Level 3b",

"url": "https://newapi.getpop.org/level-1/level-2/level-3b/",

"children": []

}

]

}

]

},

{

"id": 742,

"objectID": "146",

"parentID": null,

"label": "Lorem Ipsum",

"url": "https://newapi.getpop.org/lorem-ipsum/",

"children": []

}

]

}

}

}

This method has the following advantages:

However, this method also has a clear disadvantage: we lose the strong typing from GraphQL. Instead of receiving a menu item with strongly typed fields — url as a URL, label as a String, objectID as an ID, and so on — we get a plain object that will not be understood by the GraphQL tools and clients, such as Apollo or Relay. Hence, we won’t really make the most out of GraphQL’s benefits.

We come to another issue when we need to fetch entities that are driven by the user interface and stored in the database. For instance, WordPress allows for settings menus whose options names are dynamically created, and meta values to be dynamically created by either site admins or the themes and plugins they choose. This means these menu options and meta values are not known or shared in advance with the GraphQL server.

In this section, we’ll explore how settings are delivered by two GraphQL servers for WordPress, WPGraphQL and the GraphQL API for WordPress.

WPGraphQL has mapped the settings under a special type, GeneralSettings, that contains these fields:

# The general setting type

type GeneralSettings {

# A date format for all date strings.

dateFormat: String

# Site tagline.

description: String

# This address is used for admin purposes, like new user notification.

email: String

# WordPress locale code.

language: String

# A day number of the week that the week should start on.

startOfWeek: Int

# A time format for all time strings.

timeFormat: String

# A city in the same timezone as you.

timezone: String

# Site title.

title: String

# Site URL.

url: String

}

In this context, WPGraphQL is opinionated, having decided in advance which options are important enough to have already been included in its schema. If there is an option the application needs and it’s not there — say, homeurl, which is different than the site URL — then the developer must extend the schema.

The GraphQL API for WordPress takes a different approach: the options are themselves not hardcoded in the schema, but are accessed via a single option field that receives the name of the option:

type Root {

option(name: String): AnyScalar

}

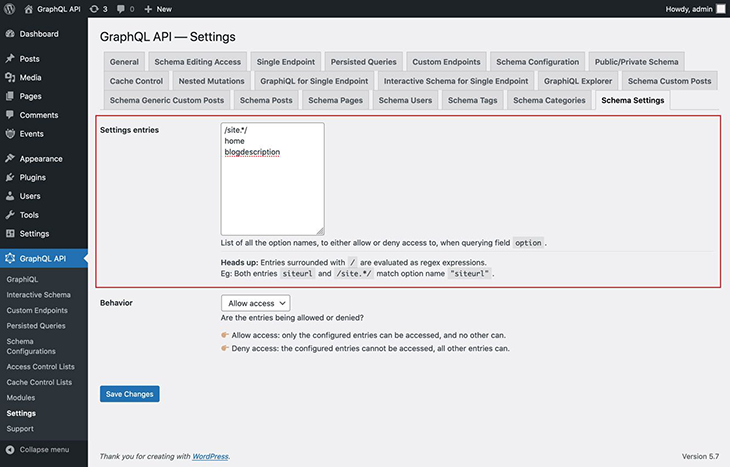

Not all options are meant to be exposed via the API; the site’s admin must explicitly safelist them, either by their full name or a regex, in the plugin settings:

Now, the query can fetch the safelisted options:

{

siteURL: option(name: "home")

siteName: option(name: "blogname")

siteDescription: option(name: "blogdescription")

}

This approach is not opinionated in advance. If the application needs an extra option, it can be made available to the API as a configuration and stored in the database, so there’s no need to modify the code to extend the GraphQL schema.

The disadvantage of this approach is that the strict typing is still lost. In WPGraphQL’s approach, the field description has the type String and startOfWeek has type Int, but in the GraphQL API for WP approach, the option field is always of type AnyScalar, which is a custom type used to represent all the inbuilt types (String, Int, Float, Boolean, and ID).

So far, we have seen that the solutions for the two different use cases exposed above have several disadvantages:

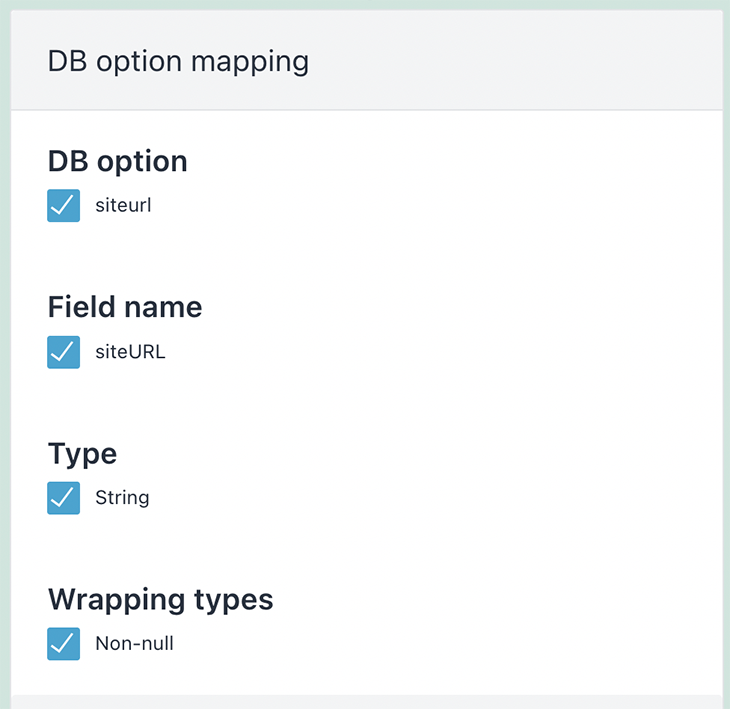

A solution to avoid these drawbacks is to generate the GraphQL API automatically from the different inputs, including the data entered by the site’s admin into the CMS. With such a method, there would be no need to employ a developer to extend the schema, and we won’t lose the benefit of GraphQL’s strict typing.

What would this look like? Concerning the example to expose settings, the GraphQL server would allow us to select the options that must be exposed in the API via some configuration page, and request to define their types. With this input, the GraphQL server could then generate the GraphQL API schema, adding one field per selected option, which would be of the expected type.

This solution is, however, not easy to implement.

Particularly when working with SDL-first GraphQL servers, we must provide the GraphQL schema via SDL, which conflicts with the idea of having the server automatically generate the schema. For code-first servers, there is no inherent conflict, but the implementation will nevertheless likely be non-trivial because we need to satisfy the features of the CMS we’re working with.

Our best bet is for the GraphQL server to already implement this approach, customized for a specific CMS. For instance, because both WPGraphQL and the GraphQL API for WordPress are custom-made for WordPress, they could very well automatically produce the schema taking into account all inputs from this CMS, including the user-provided menus, and the options from the DB.

For JS-based servers, there are already services which automatically generate the GraphQL schema, such as PostGraphile and Hasura. However, these services use the DB as input to generate the GraphQL schema (PostgreSQL for PostGraphile; PostgreSQL, and a few others for Hasura), and not a CMS. Hence, custom features offered by some particular CMSs, such as configuring what options to expose, or how many levels nested comments can span, would require custom development.

When the API is meant to be used by third parties, then automatically generating the GraphQL schema should be done carefully, tackling a specific feature at a time. This is because this approach may not produce a well designed API, which could confuse your users and, more importantly, expose information that makes the API insecure. We must make sure that the input data, which contains admin-side information (such as a table column name), does not leak to the public-facing layer.

We explored two different circumstances in which GraphQL imposes a way to work that may run contrary to how an application works, specifically those based on a CMS like WordPress.

The first case involves the nesting of menu items and comments. The best way to deal with it is to add additional nesting layers to the GraphQL query for menu items and comments, even if these extra levels are not initially needed, as to allow the site’s admin to increase this number from within the user interface without having to employ a developer to update code and deploy the changes.

The second case involves querying data that is created dynamically, as happens with settings and meta values. We explored two approaches, as implemented by WPGraphQL and the GraphQL API for WP, which both have drawbacks. The best solution would be to combine them, having the GraphQL schema be generated dynamically from configuration provided by the site’s admin via a user interface.

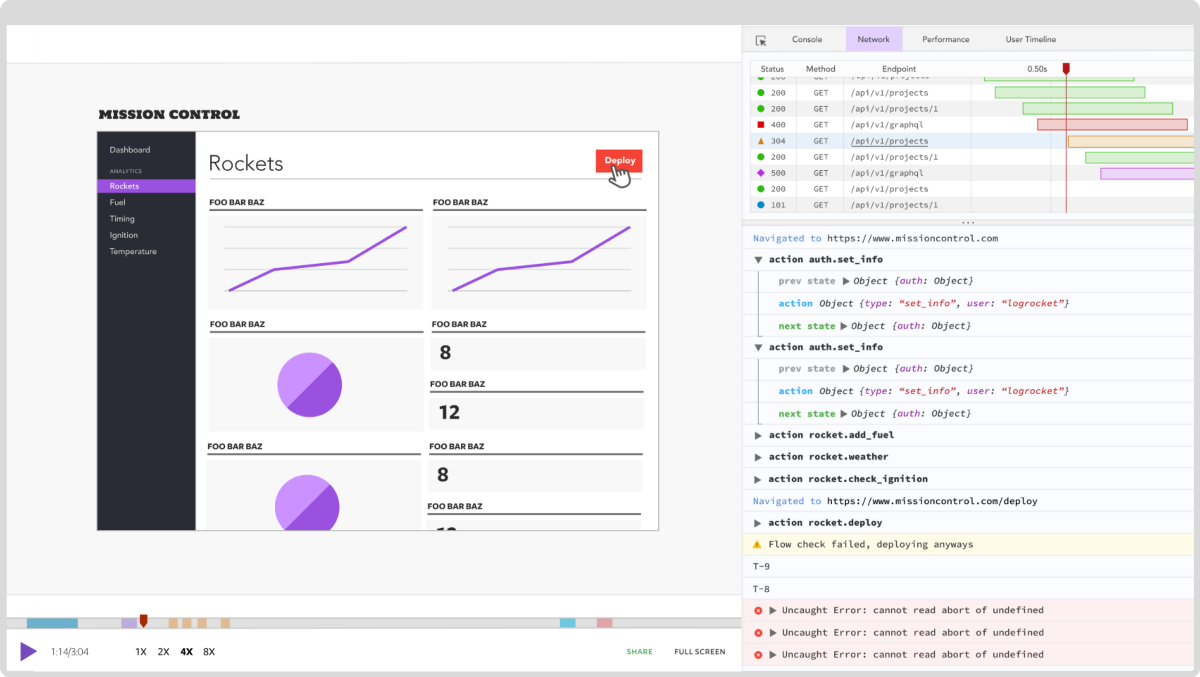

While GraphQL has some features for debugging requests and responses, making sure GraphQL reliably serves resources to your production app is where things get tougher. If you’re interested in ensuring network requests to the backend or third party services are successful, try LogRocket.

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork around why bugs happen by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings — compatible with all frameworks.

LogRocket's Galileo AI watches sessions for you, instantly aggregating and reporting on problematic GraphQL requests to quickly understand the root cause. In addition, you can track Apollo client state and inspect GraphQL queries' key-value pairs.

Solve coordination problems in Islands architecture using event-driven patterns instead of localStorage polling.

Signal Forms in Angular 21 replace FormGroup pain and ControlValueAccessor complexity with a cleaner, reactive model built on signals.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the February 25th issue.

Explore how the Universal Commerce Protocol (UCP) allows AI agents to connect with merchants, handle checkout sessions, and securely process payments in real-world e-commerce flows.

Would you be interested in joining LogRocket's developer community?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

4 Replies to "Fetching dynamically structured data in a CMS with GraphQL"

Been playing around with WPEngine’s FaustJS. It uses gqty to dynamically build GraphQL queries, which means you can just loop through the indeterminate number of children without worrying about how many levels you need to nest your queries.

Sounds interesting, I’d like to learn more, if you don’t mind. How do you like using gqty versus composing the queries manually? Do you like the experience, or is it too hand-off? Benefits/disadvantages you’ve encountered so far?

From my experience, there’s 2 types of devs in the WP Headless space: frontend devs looking to use WP as a cms, and WP devs looking to break free of the native php frontend shackles while still benefiting from the ecosystem.

I’m in the latter camp, and gqty definitely helps me and my WP_Query() trained brain, where I can focus on what to do with the data instead of wasting time writing hundreds of lines of gql in order to retrieve it.

Only downside _for me_ is that the docs are pretty sparse, though the folks at gqty and WPEngine’s discords are very helpful. There are some advanced graphql cases that gqty doesn’t handle… Or so I’m told, haven’t run into any issues yet, but that’s prob because I anyway don’t know how to do those things in graphql. That said, there’s nothing stopping you from using regular graphql for a specific query (like how Gatsby users handle mutations).

Great, thanks for the info!