Errors are an inevitable part of every programming language, and Rust is no exception. While Rust’s design encourages writing error-free code, neglecting proper error handling can lead to unexpected failures and unreliable software.

By learning how to handle errors efficiently, you’ll not only write cleaner, more maintainable Rust code, but also create a more predictable and user-friendly software.

In this guide, we’ll cover how to implement and use several Rust features and popular third-party error-handling libraries like anyhow, thiserror, and color-eyre to effectively handle errors. We’ll also discuss some common errors you might encounter in Rust and how to fix them.

Let’s get into it…

Not all errors are created equally. Rust errors, for example, are categorized into recoverable and unrecoverable errors.

You can interpret and return a response to recoverable errors. Meanwhile, unrecoverable errors require your program to terminate immediately.

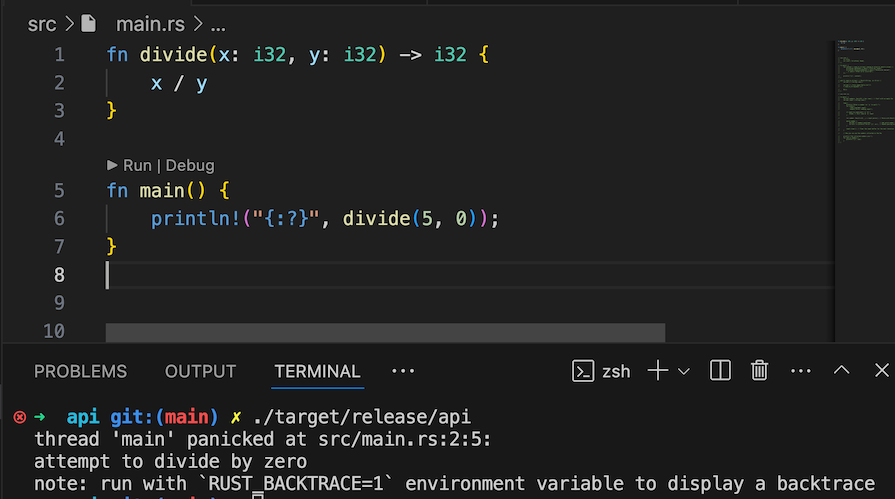

Even though unrecoverable errors leads to program termination, you can still provide informative error messages or take actions like logging the error. We can provide informative messages before termination with the panic! macro. Here’s an example of a code that will panic at runtime:

fn divide(x: i32, y: i32) -> i32 {

x / y

}

fn main() {

println!("{:?}", divide(5, 0));

}

The code above will throw a divide-by-zero panic response, and the program will terminate immediately with an error message that reads attempt to divide by zero as shown below:

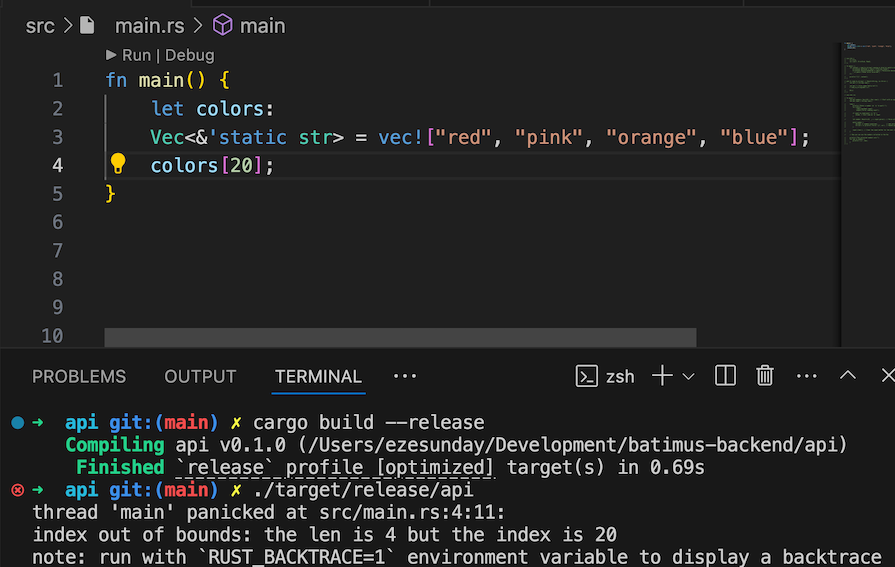

Another example could be when you are trying to access the index of a vector that is not in existence. You’ll get an index out of bounds panic response, as shown below and the program will terminate:

Most of the time, you won’t be able to anticipate this error. But when you can, you can prevent it from happening.

For example, we can prevent the divide by zero panic by making sure the division by zero does not happen in the first place. We can achieve that by returning a friendly error message or by returning a result like so:

fn divide(x: u32, y: u32) -> Result<u32, String> {

if y == 0 {

return Err("Division by zero is not supported".to_string());

}

Ok(x / y)

}

fn main() {

println!("{:?}", divide(5, 0));

}

With this implementation, we have converted the unrecoverable error to a recoverable one, and our program execution won’t be terminated.

We have seen how our code can automatically panic and terminate the program. However, if you also want to manually cause the program to panic and halt the execution, you can do so by calling the panic! macro like so:

fn main() {

panic!("Battery critically low! Shutting down to prevent data loss.");

}

By default, when a program invokes the panic! macro, it unwinds the stack and deallocates resources. This can take some time, so if you want the operating system to just take care of it, you can set the panic to abort in your Cargo.toml file:

[profile.release] panic = 'abort'

Recoverable errors are primarily handled through the Result enum. The Result enum can hold either a valid value (Ok) or an error value (Err).

In addition to the Result enum, the Option enum can also be useful when dealing with optional values. While not strictly intended for errors, the Option enum signifies the presence (Some) or absence (None) of a value, which can be useful when you’re handling errors in Rust.

The Result type signature looks like this:

Result <T, Err>

The first variant T can be any type that represents a successful execution, while the second variant Err represents an error type.

A simple example of a recoverable error is the error that occurs when you attempt to read the content of a file from the file system and the file does not exist.

Here’s a simple example:

pub fn read_file_to_string(path: &str) -> Result<String, io::Error> {

let mut file_content = String::new();

let mut file = match File::open(path) {

Ok(f) => f,

Err(e) => return Err(e),

};

match file.read_to_string(&mut file_content) {

Ok(_) => Ok(file_content),

Err(e) => Err(e),

}

}

The function above accepts a string slice — the path to the file we intend to open — and returns a a result of a String (the content of the file) or an Error (in case there is an issue reading the file). That means any function calling this function will have to consider both scenarios.

As we can see from the code, the File::open(path) method also returns a result, which makes it easier for us to handle with a match pattern in case the file path doesn’t exist:

let mut file = match File::open(path) {

Ok(f) => f,

Err(e) => return Err(e),

};

Also, we’re able to handle any error that occurs while we are reading the content of the file to the string:

match file.read_to_string(&mut file_content) {

Ok(_) => Ok(file_content),

Err(e) => Err(e),

}

This is all made possible because of the Result type. In the most basic form of handling Result types, we can use the match keyword; in other cases, you could leverage other Rust features that allow you to do similar tasks, but in an easier and more concise way. We’ll discuss the common methods in the next section.

On the other hand, the Option<T> enum helps you prevent errors that could arise from assuming a value is always present when it might not be. It allows you to return a valid value of a specific type (Some(value)) or indicate the absence of a value (None).

Here is a simple example:

#[derive(Debug)]

struct User {

name: String,

id: i32,

}

fn get_user_name_by_id(id: u32) -> Option<User> {

// Simulate fetching user data from a database

if id == 1 {

let user = User {

name: String::from("Okon"),

id: 1,

};

Some(user)

} else {

None // User not found, return None

}

}

fn main() {

match get_user_name_by_id(1) {

Some(user) => println!(

"The user {} with the Id {}, has been retrieved",

user.name, user.id

),

None => println!("User not found"),

}

}

The example above illustrates a scenario where you are trying to retrieve a user from the database. You’re not guaranteed the user is there, so there are two possible outcomes: either the user data or a None value indicating that the user does not exist.

While this is not an error per se, Option is an interesting feature to help you handle such situations.

Result and Option enumIn this next section , we’ll explore the error handling methods that Rust provides for the Result and Option enum.

.unwrap_or_else and unwrap_orUse unwrap_or_else and unwrap_or when you need to get the outcome of a Result or an Option. However, note that when something goes wrong, you’ll want to return a default.

For unwrap_or, you want to pass the default value straight up. With unwrap_or_else, you want to call a function that could probably do some math or something before returning the default value.

Here’s an example:

fn parse_int(val: &str) -> Option<i32> {

match val.parse::<i32>() {

Ok(item) => Some(item),

Err(_) => None,

}

}

fn main() {

let value = parse_int("32fg").unwrap_or(100);

let value = parse_int("12fg").unwrap_or_else(|| {

// Do something

// This closure will be called if there's an error

100

});

}

.or and or_else.or and or_else does similar things like the unwrap_ counter part in the previous section only that it doesn’t allow you to set the inner value directly but with with the variants type. For example, for an Option, we’ll add the default value with the Some() variant like so:

let value = parse_int("123f").or(Some(100));

Or the None variant like so:

let value = parse_int("123f").or(None);

Likewise, for the Result type, we’ll have either Ok or Err:

fn parse_int(val: &str) -> Option<i32> {

match val.parse::<i32>() {

Ok(item) => Some(item),

Err(_) => None,

}

}

fn main() {

let value = parse_int("123f").or(Some(100));

let value = parse_int("123f").or_else(|| {

// This closure will be called if there's an error

Some(100)

});

}

.expect vs unwrap.expect and .unwrap methods are common ways to return the inner value or success value of either a Result or Option type and a panic response.

There’s only one difference between using .expect or .unwrap. .expect allows you to return a custom message before the panic, which during debugging can help you figure out where the actual error happened. Meanwhile, .unwrap just panics without giving you enough information.

You should use .unwrap for situations where you are absolutely sure of the returned value:

let value = "123".parse::<i32>().unwrap();

And use .expect when there is even a slight chance that they could be an issue. For example, here’s a scenario where you’re trying to retrieve a value from the environment variables:

let url = std::env::var("DATABASE_URL").expect("Value is not an i32 integer");

If the DATABASE_URL is not found in the environment variables, your code will panic and and terminate the execution process.

To limit crashes, use both .expect and .unwrap sparingly and give more consideration to other error handling mechanisms, such as pattern matching or match statements.

match statements for error handlingWe can pattern-match the Result enum or the Option enum to get the result or handle the error appropriately. Here’s a simple example of how we can do that for the Option enum:

fn parse_int(val: &str) -> Option<i32> {

match val.parse::<i32>() {

Ok(item) => Some(item),

Err(_) => None,

}

}

And for the the Result enum:

fn parse_int(val: &str) -> Result<i32, ParseIntError> {

match val.parse::<i32>() {

Ok(value) => Ok(value),

Err(err) => Err(err),

}

}

This approach is more ergonomic, and you’re less likely to experience your program crashing.

? to propagate errorsUsing pattern matching as demonstrated above is great and easy to read. However, the question mark operator was released on November, 10th, 2016 to make error handling even more convenient. It’s a shorthand for an entire match operation.

For example, this entire match operation:

fn parse_int(val: &str) -> Result<i32, ParseIntError> {

match val.parse::<i32>() {

Ok(value) => Ok(value),

Err(err) => Err(err),

}

}

Can become this:

fn parse_int(val: &str) -> Result<i32, ParseIntError> {

let value = val.parse::<i32>()?;

Ok(value)

}

Technically, the ? operator returns the variant from the Result operation, either the Ok() or the Err variant. Regardless of which one gets returned, the ? operator will know to propagate it to the calling function.

Additionally, we can also chain the result or errors of multiple method calls like so:

foo()?.bar()?.baz()?

Each method propagates the Ok result or Err result to the next function in the chain. If there is an error in any of the methods, the chain is broken and the error is returned to the function calling it.

Error traitWhen your program gets complicated, you might consider creating custom errors. This approach will add context to your error handling and provide a consistent error handling interface throughout your project.

To do this in Rust, you need to implement the Error trait for your custom error type. The std::error::Error trait represents the basic expectations for error values and allows us to convert our Enum or Struct to an Err type.

The Error trait requires you to implement Display and Debug trait for your own Error type, as the signature is like this:

use std::fmt::{Debug, Display};

pub trait Error: Debug + Display {

//

}

So, if we have a custom error like so:

enum CustomError {

FileNotFound,

PermissionDenied,

UnknownError(String),

}

Then we can derive the Debug trait and implement the Display trait as shown below:

use std::{error::Error, fmt};

#[derive(Debug)]

enum CustomError {

FileNotFound,

PermissionDenied,

UnknownError(String),

}

impl fmt::Display for CustomError {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut fmt::Formatter) -> fmt::Result {

match self {

CustomError::FileNotFound => write!(f, "File not found"),

CustomError::PermissionDenied => write!(f, "Permission denied"),

}

}

}

The above code should work just fine as a basic CustomError. However, you can add the impl Error block to get the additional implementations from the Error trait:

impl Error for CustomError {}

If you want to get this even further to make your code more ergonomic, you might want to implement your CustomError using the From trait. Let’s take a look at the Rust documentation to understand why it’s important to do so:

While performing error handling it is often useful to implement

Fromfor your own error type. By converting underlying error types to our own custom error type that encapsulates the underlying error type, we can return a single error type without losing information on the underlying cause. The ‘?’ operator automatically converts the underlying error type to our custom error type withFrom::from.

The From trait is a trait used for value conversion between types. So, we could typically use it to convert errors from one type to another — like in this example below, where we convert the Error trait from from the standard library to MyError, our own custom error:

#[derive(Debug)]

enum MyError {

InvalidInput(String),

IoError(std::io::Error),

}

impl From<std::io::Error> for MyError {

fn from(err: std::io::Error) -> Self {

MyError::IoError(err)

}

}

Implementing your own custom error handling from the ground up can become messy sometimes, as you’ll have lots of boilerplate code. Using popular and well tested open source libraries like thiserror, color-eyre, and anyhow could simplify your error handling system and allow you to focus more on your business logic.

Below is a table showing a comparison of these three top error handling libraries, including their benefits and use cases:

| Feature | thiserror | anyhow | color-eyre |

|---|---|---|---|

| Error type definition | Uses macros to define custom error types | Works with any type implementing the Error trait | Works with any type implementing the Error trait |

| Boilerplate reduction | Reduces boilerplate for defining error types | Reduces boilerplate for error handling | Reduces boilerplate for error handling with colorful backtraces |

| Context addition | Limited context addition during error creation | Allows adding context to any error type | Allows adding context to any error type |

| Backtrace information | Basic backtrace | Basic backtrace | More detailed and colorful backtrace information |

| Use case | Ideal for libraries defining custom error types | Ideal for applications working with various error types | Ideal for applications wanting informative error messages with colorful backtraces |

| Common usage | #[derive(Error)] macro | anyhow::Result<T, E> type and conversion methods | eyre::Result<T, E> type and conversion methods |

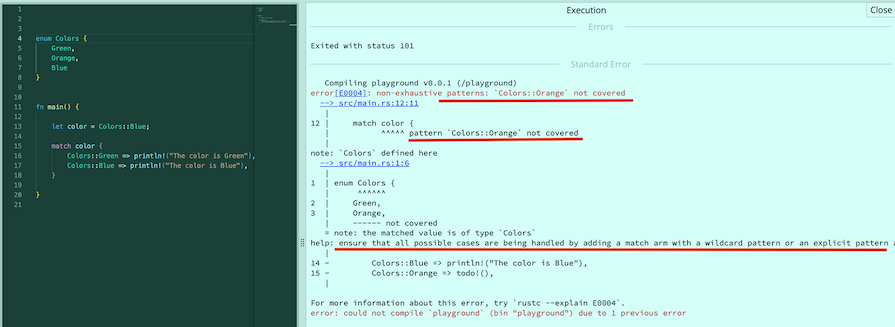

Often, the compiler won’t even let you compile Rust code containing errors. So, when these errors happen, it’s crucial that you understand why the error is happening in the first place. However, there could be various potential causes for Rust errors, so let’s explore some best practices for getting to the root cause.

One of the best things about Rust is that it simplifies debugging. In most cases, if you pay attention to the error message, you’ll find exactly what is wrong in plain English, often with suggestions on how to fix the issue.

Errors like can't find rust compiler could simply indicate an improper Rust installation. Again, here is a simple example of a situation where all the variants in an enum are not exhaustive. The compiler provides enough information and provides context and suggestions to help solve the problem:

Integrating logging and tracing in your codebase can help you visualize errors and understand the state of your system when issues occur. This is particularly useful for diagnosing problems in production environments.

unwrap and expect wiselyunwrap and expect can cause panics if used carelessly. You should only use them when you’re certain that the value is not an Err or None. If in doubt, use proper error handling instead to prevent unexpected behaviors in production.

For example, instead of the following usage of unwrap:

let value = some_option.unwrap();

Or this example of expect:

let value = some_option.expect("Expected a value, but got None");

You could use match for a better result:

let value = match some_option {

Some(v) => v,

None => {

eprintln!("Error: expected a value, but got None");

return;

},

};

I enjoy working with Rust. In fact, the way Rust makes handling errors a lot easier is a blessing.

Throughout this guide, we’ve covered several ways you can handle errors in Rust using the Result and Option types. We also highlighted some functions and features that allow you to handle Rust errors more ergonomically. I hope it helps you become a better Rust developer.

Happy hacking!

Debugging Rust applications can be difficult, especially when users experience issues that are hard to reproduce. If you’re interested in monitoring and tracking the performance of your Rust apps, automatically surfacing errors, and tracking slow network requests and load time, try LogRocket.

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork around why bugs happen by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings — compatible with all frameworks.

LogRocket's Galileo AI watches sessions for you, instantly identifying and explaining user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

Modernize how you debug your Rust apps — start monitoring for free.

Would you be interested in joining LogRocket's developer community?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

Not sure if low-code is right for your next project? This guide breaks down when to use it, when to avoid it, and how to make the right call.

Compare Firebase Studio, Lovable, and Replit for AI-powered app building. Find the best tool for your project needs.

Discover how to use Gemini CLI, Google’s new open-source AI agent that brings Gemini directly to your terminal.

This article explores several proven patterns for writing safer, cleaner, and more readable code in React and TypeScript.