The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

In the JavaScript/Node.js ecosystem, there are a host of tools used for linting our code. Some of the most popular ones include JSLint, JSHint and ESLint. These tools help ensure that issues or errors (mainly programmer-induced) in our source code can be detected via static code analysis – parsing and analyzing source code and returning a new result.

These tools exist so that developers adhere to best practices and stick to a uniform standard in terms of code style. In return, this not only helps prevent bugs (thereby reducing a lot of back and forth in debugging) but also enforces code consistency in terms of style.

Although linters have existed before now, in the past they were mostly used as a utility library to analyze and fix issues in the C programming language and other Unix-based softwares.

These days, linting describes the process of applying rules on a codebase that help catch bugs and code patterns that violate those rules specified in a configuration file. In this post, we are going to explore some of these linting rules when working in Node.

We will also learn how these rules can help improve coding standards and enforce best practices and consistency amongst developers. The end goal is that code is consistent, cleaner, and easy to understand by the machine or interpreter.

Because a codebase can potentially grow so large overtime, and due to the nature of the JavaScript programming language, linters help provide a sort of mechanism to check for programmer errors or bugs in a codebase in order to help fix them.

Usually, there is a configuration file with a bunch of rules outlined with best practices in mind, thus ensuring code quality and great syntax formatting. While different developers can decide to make use of different linting tools in their projects, the end goal most of the time is usually the same.

For the JavaScript language, some of these rules have been presented and explained earlier in the book How JavaScript Works by the famous author of JSLint, Douglas Crockford.

Some of the outlined rules define what happens and how the program reacts to certain issues introduced by the programmer. For example, what should happen when there is an unused variable or inaccessible code, or even wrong types, in our code?

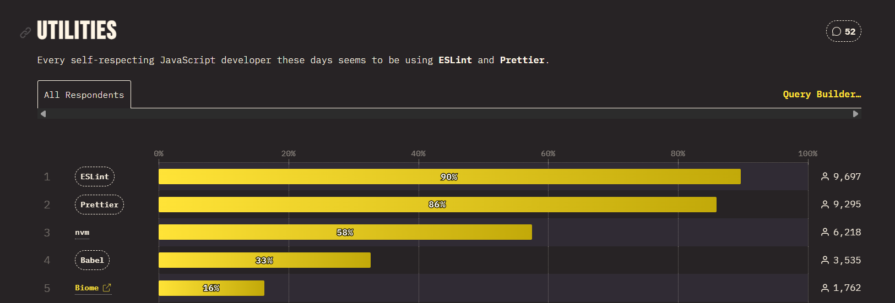

Linters also come in handy as useful tools for code formatting, although nowadays we have style guides like Prettier, a popular tool that handles style and formatting rules and enables the programmer adhere to language-specific best practices.

Linting rules are important in interpreted languages like JavaScript, as they ensure errors or bugs are quickly spotted on the fly, just before runtime.

This is unlike compiled languages like Go and TypeScript (a JavaScript superset), where errors are spotted and thrown during the code compilation phase.

In essence, linting rules will run through our source code and find issues relating to:

For a good example, say we are working on an API in JavaScript or Node, and we have an undefined variable passed in as an argument to a function. Without actually using a linter or working with compiled languages, or even writing any unit tests, it would be difficult to detect or fix these sort of issues.

By analyzing our code before runtime, we can be assured that at the end of the day, we have built a comfortable level of code reliability and quality.

Overall, linting rules in Node are especially helpful when working in large cross-functional teams where developers with different ideologies and patterns of writing code collaborate on the same codebase. In essence, these rules ensures code quality is kept in check at all times.

With the increased usage of linters in the JavaScript community, style guides were invented to help fix stylistic rules for linters.

Style guides work by reprinting a particular portion of a codebase with inconsistent styles. Therefore, we do not necessarily have to specify stylistic rules with linters, because we can simply configure a style guide to handle that part, with linters to handle rules specifically relating to code quality.

With ESlint, we can achieve both stylistic and formatting rules. This means that the rules we configure or specify with linters can be applied to both the code quality and formatting aspect. However, it is usually used alongside style guides like Prettier, which are specifically meant for stylistic purposes.

One benefit of style guides is that they enforce a certain way of writing code (supposed best practices) that all team members working on the same codebase must adapt or adhere to. Nowadays, one of the most popular style guide is Javascript Standard Style, a JavaScript style guide that comes with automatic code fixers and linters.

Under the hood, Javascript Standard Style is built on top of ESLint. As such, no configuration file is needed as there are already pre-configured style rules, formatting, and code quality rules built in to the tool.

If you have noticed, I have made specific reference to ESLint. This is because it is one of the most-used and popular linting tools in the JavaScript ecosystem today. In fact, it is gradually becoming a standard for Node apps, with around 19 million weekly downloads per week on npm.

While the other linting libraries mentioned earlier can work in any environment where JavaScript runs, we will be making lots of references to the ESlint library to explore some linting rules. However, these rules are all encompassing and generally applicable.

In this section, we will explore how these rules can help developers to write better code. Specifically, we will be making reference to the ESLint library and exploring some of its rules. But before we begin, let us look at some of its features.

According to the documentation, ESLint is a syntax checker and formatter for JavaScript. It is easily extensible and comes with a bunch of custom plugins for each rule. We can also configure our own rules by writing our own plugins.

The library improves and fixes some of the shortcomings associated with earlier linting tools, which were not as extensible and customizable and prevented developers from creating their own rules.

ESLint comes with a couple of philosophies that allow every rule to stand alone and be turned on and off at any time. One of the greatest benefits is that the library does not favor any particular coding style, meaning developers are free to add or remove rules based on the needs and use cases of their projects.

Further, ESLint comes with two major rule categories, comprising of different subcategories.

First is the API that contains rules relating to code quality. They are further subdivided into different categories for easier understanding:

Secondly, we have stylistic rules that relate to style guidelines. These rules are usually subjective and are based on individual preferences. Don’t forget that we can also decide to combine ESLint with a style guide like Prettier to handle these stylistic rules.

no-unused-vars is aimed at eliminating unused variables, functions, and function parameters. By default this rule is enabled with the all option for variables and after-used for arguments. A link to the arguments can be found here in the documentation.

{

"rules": {

"no-unused-vars": ["error", { "vars": "all", "args": "after-used", "ignoreRestSiblings": false }]

}

}

radix – When using the parseInt() function it is common to omit the second argument (the radix) and let the function try to determine from the first argument what type of number it is.

In the example below, ESLint would flag the first use of parseInt below as unsafe:

/ without a radix argument - Unsafe const count = parseInt(countString); // with a radix parameter specified - Safe const count = parseInt(countString, 10);

no-use-before-define will warn the developer when it encounters a reference to an identifier that has not yet been declared. Prior to ES6, variable and function declarations were hoisted to the top of a scope, so it’s possible to use variables before they are declared.

See the rule config below:

{

"no-use-before-define": ["error", { "functions": true, "classes": true }]

}

no-useless-catch reports catch clauses that only throw the generic caught error. A catch clause that returns the original error is redundant, and has no effect on the runtime behavior of the program.

See correct usage of the rule below:

try {

runCode();

} catch (e) {

handleAxiosError(e);

}

no-self-compare – Comparing a variable against itself is usually an error. This is because, it is confusing to whoever is reading the code and could potentially introduce a runtime error.

no-useless-return aims to report redundant return statements. A return; statement with nothing after it is redundant, and has no effect on the runtime behavior of a function.

no-const-assign disallows reassigning const variables. We cannot modify variables that are declared using const keyword, as this will raise a runtime error.

no-useless-constructor disallows creating unnecessary constructor functions. As such, it is unnecessary to provide an empty constructor or one that simply delegates into its parent class.

prefer-destructuring – With ES6, a new syntax was added for creating variables from an array index or object property, called destructuring.

no-param-reassign – Often, assignment to function parameters is unintended and indicative of a mistake or programmer error. This rule disallows reassigning function parameters.

max-len is used to enforce a maximum line length. In order to aid in readability and maintainability, coders have developed a convention to limit lines of code to X number of characters (traditionally 80).

no-mixed-spaces-and-tabs disallows mixed spaces and tabs for indentation. Most code conventions require either tabs or spaces be used for indentation. As such, it’s usually an error if a single line of code is indented with both tabs and spaces.

keyword-spacing– As an important part of the language, style guides often refer to the spacing that should be used around keywords. This rule enforces consistent spacing before and after keywords.

no-ternary disallows ternary operators. The ternary operator is used to conditionally assign a value to a variable. Some believe that the use of ternary operators leads to unclear code.

camelcase enforces camelcase naming convention. This rule looks for any underscores (_) located within the source code. It ignores leading and trailing underscores and only checks those in the middle of a variable name.

Also, it is worthy to note that some problems reported by these rules are automatically fixable with the --fix command line option. Also, some problems reported by the rule are manually fixable by editor suggestions.

As a side note, npm-package-json-lint is a configurable linter to enforce standards in npm package.json files. Code Conventions for the JavaScript Programming Language is a document detailing community standards for JavaScript code style.

Linters help spot and eventually fix issues and problems in our code. They scan the source code and report syntax errors and bugs, and enforce conventions in our code styles to help improve overall code quality.

As we may already know, different people have different patterns of writing code. Linters with style guides contain some rules and best practices relating to the kind of styles we adopt, thereby enforcing a certain level of consistency in a code base.

In a nutshell, this post has explored some linting rules applicable in the Node ecosystem and how they help entrench and imbue common standard across teams. It also allows team members to write clean, readable, and legible code.

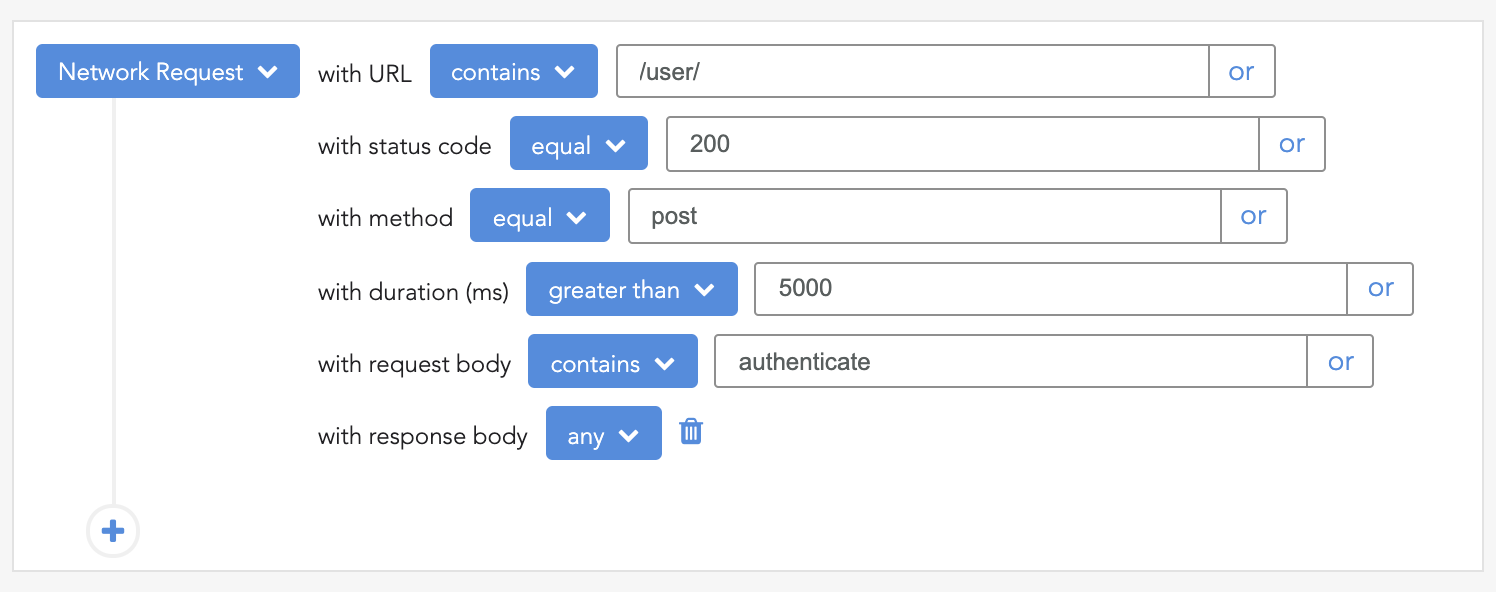

Monitor failed and slow network requests in production

Monitor failed and slow network requests in productionDeploying a Node-based web app or website is the easy part. Making sure your Node instance continues to serve resources to your app is where things get tougher. If you’re interested in ensuring requests to the backend or third-party services are successful, try LogRocket.

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork around why bugs happen by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings — compatible with all frameworks.

LogRocket's Galileo AI watches sessions for you, instantly identifying and explaining user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

LogRocket instruments your app to record baseline performance timings such as page load time, time to first byte, slow network requests, and also logs Redux, NgRx, and Vuex actions/state. Start monitoring for free.

If your AI app or agent works perfectly in development but falls apart in production, you’re not alone. In a […]

Compare ESLint and Oxlint, benchmark real speed gains, and learn when migrating to Oxlint makes sense for modern JavaScript teams.

Discover five practical ways to scale knowledge sharing across engineering teams and reduce onboarding time, bottlenecks, and lost context.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the March 4th issue.

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now