Events are everywhere in a web application. From the DOMContentLoaded event, which is triggered immediately when the browser is done loading and parsing HTML, to the unload event, which is triggered just before the user leaves your site, the experience of using a web app is essentially just a series of events. For developers, these events help us determine what just happened in an application, what a user’s state was at a specific time, and more.

Sometimes, the available JavaScript events don’t adequately or correctly describe the state of an application. For example, when a user login fails and you want the parent component or element to know about the failure, there is no login-failed event or anything similar available to be dispatched.

Fortunately, there’s a way to create JavaScript custom events for your application, which is what we’ll cover in this tutorial.

We’ll go over the following in detail:

To follow along with this tutorial, you should have basic knowledge of:

Let’s get started!

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

Custom events can be created in two ways:

Event constructorCustomEvent constructorCustom events can also be created using document.createEvent, but most of the methods exposed by the object returned from the function have been deprecated.

A custom event can be created using the event constructor, like this:

const myEvent = new Event('myevent', {

bubbles: true,

cancelable: true,

composed: false

})

In the above snippet, we created an event, myevent, by passing the event name to the Event constructor. Event names are case-insensitive, so myevent is the same as myEvent and MyEvent, etc.

The event constructor also accepts an object that specifies some important properties regarding the event.

bubblesThe bubbles property specifies whether the event should be propagated upward to the parent element. Setting this to true means that if the event gets dispatched in a child element, the parent element can listen on the event and perform an action based on that. This is the behavior of most native DOM events, but for custom events, it is set to false by default.

If you only want the event to be dispatched at a particular element, you can stop the propagation of the event via event.stopPropagation(). This should be in the callback that listens on the event. More on this later.

cancelableAs the name implies, cancelable specifies whether the event should be cancelable.

Native DOM events are cancelable by default, so you can call event.preventDefault() on them, which will prevent the default action of the event. If the custom event has cancelable set to false, calling event.preventDefault() will not perform any action.

composedThe composed property specifies whether an event should bubble across from the shadow DOM (created when using web components) to the real DOM. If bubbles is set to false, the value of this property won’t matter because you’re explicitly telling the event not to bubble upward. However, if you want to dispatch a custom event in a web component and listen on it on a parent element in the real DOM, then the composed property needs to be set to true.

A drawback of using this method is that you can’t send data across to the listener. However, in most applications, we would want to be able to send data across from where the event is being dispatched to the listener. To do this, we can use the CustomEvent controller

You can’t also send data using native DOM events. Data can only be gotten from the event’s target.

CustomEvent constructorA custom event can be created using the CustomEvent constructor:

const myEvent = new CustomEvent("myevent", {

detail: {},

bubbles: true,

cancelable: true,

composed: false,

});

As shown above, creating a custom event via the CustomEvent constructor is similar to creating one using the Event constructor. The only difference is in the object passed as the second parameter to the constructor.

When creating events with the Event constructor, we were limited by the fact that we can’t pass data through the event to the listener. Here, any data that needs to be passed to the listener can be passed in the detail property, which is created when initializing the event.

After creating the events, you need to be able to dispatch them. Events can be dispatched to any object that extends EventTarget, and they include all HTML elements, the document, the window, etc.

You can dispatch custom events like so:

const myEvent = new CustomEvent("myevent", {

detail: {},

bubbles: true,

cancelable: true,

composed: false,

});

document.querySelector("#someElement").dispatchEvent(myEvent);

To listen for the custom event, add an event listener to the element you want to listen on, just as you would with native DOM events.

document.querySelector("#someElement").addEventListener("myevent", (event) => {

console.log("I'm listening on a custom event");

});

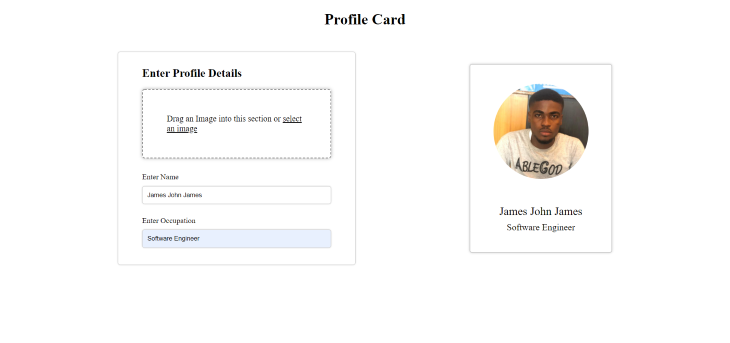

To show how to use custom events in a JavaScript application, we’ll build a simple app that allows users to add a profile and automatically get a profile card.

Here is what the page will look like when we’re done:

Create a folder, name it anything you like, and create an index.html file in the folder.

Add the following to index.html:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0" />

<title>Custom Events Application</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="style.css" />

</head>

<body>

<h1>Profile Card</h1>

<main>

<form class="form">

<h2>Enter Profile Details</h2>

<section>

Drag an Image into this section or

<label>

select an image

<input type="file" id="file-input" accept="image/*" />

</label>

</section>

<div class="form-group">

<label for="name"> Enter Name </label>

<input type="text" name="name" id="name" autofocus />

</div>

<div class="form-group">

<label for="occupation"> Enter Occupation </label>

<input type="text" name="occupation" id="occupation" />

</div>

</form>

<section class="profile-card">

<div class="img-container">

<img src="http://via.placeholder.com/200" alt="" />

</div>

<span class="name">No Name Entered</span>

<span class="occupation">No Occupation Entered</span>

</section>

</main>

<script src="index.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

Here, we’re adding the markup for the page.

The page has two sections. The first section is a form, which allows the user to do the following:

The data gotten from the form will be displayed in the second section, which is the profile card. The second section just contains some placeholder text and images. The data received from the form will overwrite the content placeholder data.

Create a style.css file and populate it with the following:

* {

box-sizing: border-box;

}

h1 {

text-align: center;

}

main {

display: flex;

margin-top: 50px;

justify-content: space-evenly;

}

.form {

flex-basis: 500px;

border: solid 1px #cccccc;

padding: 10px 50px;

box-shadow: 0 0 3px #cccccc;

border-radius: 5px;

}

.form section {

border: dashed 2px #aaaaaa;

border-radius: 5px;

box-shadow: 0 0 3px #aaaaaa;

transition: all 0.2s;

margin-bottom: 30px;

padding: 50px;

font-size: 1.1rem;

}

.form section:hover {

box-shadow: 0 0 8px #aaaaaa;

border-color: #888888;

}

.form section label {

text-decoration: underline #000000;

cursor: pointer;

}

.form-group {

margin-bottom: 25px;

}

.form-group label {

display: block;

margin-bottom: 10px;

}

.form-group input {

width: 100%;

padding: 10px;

border-radius: 5px;

border: solid 1px #cccccc;

box-shadow: 0 0 2px #cccccc;

}

#file-input {

display: none;

}

.profile-card {

flex-basis: 300px;

border: solid 2px #cccccc;

border-radius: 5px;

box-shadow: 0 0 5px #cccccc;

padding: 40px 35px;

align-self: center;

display: flex;

flex-direction: column;

justify-content: center;

align-items: center;

}

.img-container {

margin-bottom: 50px;

}

.img-container img {

border-radius: 50%;

width: 200px;

height: 200px;

}

.profile-card .name {

margin-bottom: 10px;

font-size: 1.5rem;

}

.profile-card .occupation {

font-size: 1.2rem;

}

Lastly, create an index.js file so you can add functionality to the application.

The first functionality we’ll add to the application is the ability to upload images. For this, we’ll support drag-and-drop as well as manual upload.

Add the following to the JavaScript file:

const section = document.querySelector(".form section");

section.addEventListener("dragover", handleDragOver);

section.addEventListener("dragenter", handleDragEnter);

section.addEventListener("drop", handleDrop);

/**

* @param {DragEvent} event

*/

function handleDragOver(event) {

// Only allow files to be dropped here.

if (!event.dataTransfer.types.includes("Files")) {

return;

}

event.preventDefault();

// Specify Drop Effect.

event.dataTransfer.dropEffect = "copy";

}

/**

* @param {DragEvent} event

*/

function handleDragEnter(event) {

// Only allow files to be dropped here.

if (!event.dataTransfer.types.includes("Files")) {

return;

}

event.preventDefault();

}

/**

* @param {DragEvent} event

*/

function handleDrop(event) {

event.preventDefault();

// Get the first item here since we only want one image

const file = event.dataTransfer.files[0];

// Check that file is an image.

if (!file.type.startsWith("image/")) {

alert("Only image files are allowed.");

return;

}

handleFileUpload(file);

}

Here, we’re selecting the section from the DOM. This allows us listen on the appropriate events that are required to allow drag-and-drop operations — namely, dragover, dragenter, and drop.

For a deeper dive, check out our comprehensive tutorial on the HTML drag-and-drop API.

In the handleDragOver function, we’re ensuring that the item being dragged is a fileand setting the drop effect to copy. handleDragEnter also performs a similar function, ensuring that we’re only handling the dragging of files.

The actual functionality happens when the file is dropped, and we handle that using handleDrop. First, we prevent the browser’s default action, which is to open a file before delivering it.

We validate that the file is an image. If it’s not, we send an error message to let the user know we only accept image files. If the validation passes, we proceed to process the file in the handleFileUpload function, which we’ll create next/

Update index.js with the following:

/**

* @param {File} file

*/

function handleFileUpload(file) {

const fileReader = new FileReader();

fileReader.addEventListener("load", (event) => {

// Dispatch an event to the profile card containing the updated profile.

dispatchCardEvent({

image: event.target.result,

});

});

fileReader.readAsDataURL(file);

}

const profileCard = document.querySelector(".profile-card");

const CARD_UPDATE_EVENT_NAME = "cardupdate";

function dispatchCardEvent(data) {

profileCard.dispatchEvent(

new CustomEvent(CARD_UPDATE_EVENT_NAME, {

detail: data,

})

);

}

The handleFileUpload function takes in a file as a parameter and attempts to read the file as a data URL using a file reader.

The FileReader constructor extends from EventTarget, which enables us to listen in on events. The load event is fired after the image is loaded — in our case, as a data URL.

You could also load images in other formats. MDN has a great documentation on the FileReader API if you’re looking to learn more about file readers.

Once the image has been loaded, we need to display it in the profile card. For this, we’ll dispatch a custom event, cardupdate, to the profile card. dispatchCardEvent handles creating and dispatching the event to the profile card.

If you recall from the section above, custom events have a detail property, which can be used to pass data around. In this case, we’re passing an object containing the image URL, which was gotten from the file reader.

Next, we need the profile card to listen for card updates and update the DOM accordingly.

profileCard.addEventListener(CARD_UPDATE_EVENT_NAME, handleCardUpdate);

/**

* @param {CustomEvent} event

*/

function handleCardUpdate(event) {

const { image } = event.detail;

if (image) {

profileCard.querySelector("img").src = image;

}

}

As shown above, you simply add the event listener as you normally would and call the handleCardUpdate function when the event is triggered.

handleCardUpdate receives the event as a parameter. Using object destructuring, you can get the image property from event.detail. Next, set the src attribute of the image in the profile card to be the image URL gotten from the event.

To allow users to upload images via the input field:

const fileInput = document.querySelector("#file-input");

fileInput.addEventListener("change", (event) => {

handleFileUpload(event.target.files[0]);

});

When a user selects an image, the change event will be triggered on file input. We can handle the upload of the first image since we only need one image for the profile card.

Now we don’t need need to do anything new since we developed all the functionality when adding support for drag-and-drop.

The next functionality to add is updating name and occupation:

const nameInput = document.querySelector("#name");

const occupationInput = document.querySelector("#occupation");

occupationInput.addEventListener("change", (event) => {

dispatchCardEvent({

occupation: event.target.value,

});

});

nameInput.addEventListener("change", (event) => {

dispatchCardEvent({

name: event.target.value,

});

});

For this, we’re listening on the change event and dispatching the card update event, but this time with different data. We need to update the handler to be able to handle more than images.

/**

* @param {CustomEvent} event

*/

function handleCardUpdate(event) {

const { image, name, occupation } = event.detail;

if (image) {

profileCard.querySelector("img").src = image;

}

if (name) {

profileCard.querySelector("span.name").textContent = name;

}

if (occupation) {

profileCard.querySelector("span.occupation").textContent = occupation;

}

}

Update the handleCardUpdate function to look like the above snippet. Here, again, we’re using object destructuring to get the image, name, and occupation from event.detail. After getting the data, we display them on the profile card.

It’s sometimes easier to understand your code when you think of it in terms of events — both custom and native DOM events — being dispatched. JavaScript custom events can enhance the user experience of your app when used properly. No surprise, then, that it’s included in some of the top JavaScript frameworks, such as Vue.js (in Vue, you dispatch custom events using $emit).

The code for the demo used in this tutorial is available on GitHub.

Debugging code is always a tedious task. But the more you understand your errors, the easier it is to fix them.

LogRocket allows you to understand these errors in new and unique ways. Our frontend monitoring solution tracks user engagement with your JavaScript frontends to give you the ability to see exactly what the user did that led to an error.

LogRocket records console logs, page load times, stack traces, slow network requests/responses with headers + bodies, browser metadata, and custom logs. Understanding the impact of your JavaScript code will never be easier!

React Server Components and the Next.js App Router enable streaming and smaller client bundles, but only when used correctly. This article explores six common mistakes that block streaming, bloat hydration, and create stale UI in production.

Gil Fink (SparXis CEO) joins PodRocket to break down today’s most common web rendering patterns: SSR, CSR, static rednering, and islands/resumability.

@container scroll-state: Replace JS scroll listeners nowCSS @container scroll-state lets you build sticky headers, snapping carousels, and scroll indicators without JavaScript. Here’s how to replace scroll listeners with clean, declarative state queries.

Explore 10 Web APIs that replace common JavaScript libraries and reduce npm dependencies, bundle size, and performance overhead.

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

One Reply to "Custom events in JavaScript: A complete guide"

Incredible!

I wanted to know how to make a script always active…

Currently things I write don’t work with new elements loaded via Ajax for example.

Is there a way to always work like CSS works with rules?