Building with CSS utility classes is an incredible boost to productivity and organization. It allows you to define a library of property: value pairs that power all your styles, managed from a single directory.

In this article, we’re going to cover:

Utility classes are self-descriptive, single-purpose CSS classes:

.flex {

display: flex;

}

Developers use these functional classes to build without writing additional CSS because if the style is in the library, you can use it over and over and over…

<aside class="flex flex-column bg-black">

<div class="flex align-center justify-center">

<img src="#" />

</div>

<div class="flex flex-column">

<h1>Jamie Thrift</h1>

<p class="flex align-center">

<svg>…</svg>

Head of HR

</p>

</div>

</aside>

The classes tell us exactly what they do, so developers can visualize how these elements will be laid out instead of needing to scan through the underlying CSS.

Utility classes are generated for you as part of a framework. Some of these popular tools and frameworks provide lots of styles out of the box, so you can just use class="padding-10" and be confident that the style already exists. Others give you the tools to define only the utilities you require for your project.

By configuring your library of styles in one place, you avoid littering your codebase with outliers and losing sight of what is new CSS and what has already been written somewhere else.

Working with utilities massively increases the organization of your project and promotes predictability and consistency for both developers and end users.

This mode of thinking has also materialized in the UI design camp, where there is an emergent practice of defining, reusing, and maintaining a central library of styles. These styles are ordinarily found in the Styleguide section of a Design System.

Styleguides mostly consist of the foundations of color, typography, spacing, grids, and iconography. These low-level fundamentals are a set of rules that designers follow to create consistent work.

There are quite a few frameworks, libraries and tools that have gained popularity in this space over the years. Here is a quick run-down of the history of some well-known options as they were released, alongside some case studies from developers who have taken a utility-first approach.

|

Tailwind CSS

|

Tachyons

|

iotaCSS

|

|

|

Best feature

|

Superb documentation

|

Pre-composed components for rapid development

|

Intuitive organization of components, objects, and utilities

|

|

Worst feature

|

JavaScript configuration

|

Hard to customize

|

Each set of utilities is a package

|

|

Class syntax

|

.text-2xlor…

.propertyalias-valuealias |

.f-headlineor…

.propertyalias-valuealias |

.o-type-smallor…

.namespace-propertyalias-valuealias

|

|

Responsive syntax

|

.md:flex-shrink-0or…

.breakpointalias:propertyalias-valuealias |

.w-100-mor…

.propertyalias-valuealias-breakpointalias |

u-text-right@smor…

.namespace-propertyalias-valuealias-breakpointalias |

|

Hover/focus syntax

|

.focus:outline-noneor…

.state:propertyalias-valuealias |

.hover-orangeor…

.state-propertyalias-valuealiasLimited combinations

|

.u-color-orange@hoveror…

.namespace-propertyalias-valuealias-state |

|

Built with

|

JavaScript (config)

CSS

|

CSS

|

SCSS

|

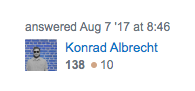

Let’s build something simple to see how these utility classes work. Here, we’re going to replicate the author component you’ll probably recognize from Stack Overflow.

I’m going to use the syntax from Tailwind CSS for this example.

Tailwindcss – Author Component

No Description

<div class="p-3">

<p class="text-gray-600">answered <span title="2017-08-07 08:46:14Z">Aug 7 '17 at 8:46</span></p>

<figure class="flex items-center mt-3">

<img class="w-10 h-10" src="https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com/525f1d2d-c241-00a9-f169-8b2061aeb3da/e53a3a2b-f539-4ab9-a3ec-7cf7a2b6a664/aleksandra_zamojc.png" alt="Photo of Konrad Albrecht" />

<figcaption class="ml-2">

<p>

<a class="text-blue-600" href="/user">Konrad Albrecht</a>

</p>

<p class="flex items-center mt-1">

<span class="font-bold text-gray-800" title="reputation score">138</span>

<span class="rounded-full w-2 h-2 bg-orange-400 ml-2"></span>

<span class="ml-1 text-gray-600" title="badge count">10</span>

</p>

</figcaption>

</figure>

</div>

“Once you name it, you get attached to it.”

Notice that none of this markup required us to name anything — because naming things is hard. We haven’t had to commit to a structure like .user or .author… which allows us to build our components faster and will leave us with less to maintain. If we later add another component that includes an author, we don’t have to rethink the naming scheme.

Truth be told, I had only quickly glanced at the Tailwind CSS documentation before starting to build that component, and I only had to look up two of the classes that I wasn’t able to guess (.rounded-full and items-center).

This means that building a component can happen in one file instead of flipping between two.

As with any approach you adopt in development, there are always compromises made. Let’s explore a few of the complications at hand.

A never-ending, wrapped line of text is very hard to decipher. When we write normal CSS, we have a few techniques that help us to scan a set of properties:

When we relocate that long list of styles back into our markup, we tend to abandon the above as it would make our HTML incredibly lengthy. This leads to exceedingly long strings of classes that are difficult to make sense of — or even lint.

Try finding the weight property in here that you’d like to adjust:

<a href="https://myurl.com/" class="bgcolor-blue bg-color-darkblue@hover bg-color-darkblue@focus radius-tlbr-3 radius-trbl-12 font-europa color-light-grey color-white@hover color-white@focus weight-medium shadow-black-thin padv-3 padh-4 whitespace-nowrap size-6rem line-thin pos-relative top-3@hover top-3@focus">Incredible pace in this place</a>

It’s worth mentioning this example doesn’t even have any responsive styles — if it were to change properties at one or two breakpoints, this could feasibly double in length.

If we go all in, some frameworks generate a class for every possible value for every property for every breakpoint and every state. That’s a huge dumpster of CSS, of which you are probably using 1 percent. Frameworks know this, and they have their own ways of dealing with it.

Tailwind CSS (350kB minified) has a section on controlling file size that recommends setting up PurgeCSS.

Purge will scan your project files to find the classes that you have used and delete the rest from your compiled CSS file. This means an extra step in your build and perhaps even a delay when running your scripts if your codebase is considerably large. There may also be inaccuracies where your programming language obscures your class names (class="bgcolor-${foo}") to worry about.

Many of CSS’s most helpful shortcuts are found in its powerful selectors. Consider, for example, a form section that fades away when the user is not interacting with it:

.fieldset:not(:focus-within):not(:hover) {

opacity: .5;

}

Or just working with pseudo-elements:

.title:after {

position: absolute;

bottom: -2px;

left: 0;

right: 0;

border-bottom: 2px solid orange;

content: '';

}

Or even something as simple as a zebra-striped table row:

.table-row:nth-child(odd) {

background-color: grey;

}

To use (fairly common!) styles like these, you would likely end up maintaining some custom CSS alongside your utility framework, or using components in iotaCSS.

Not only that, but being able to target using the cascade is also a huge time-saver when laying out elements — like deploying everybody’s favorite lobotomized owl selector:

.margin-top-siblings-2 > * + * {

margin-top: 2rem;

}

These time-saving styles are not provided by default in any of the frameworks I’ve seen, which means you’ll end up adding a lot more classes in you markup to compensate.

Having provided both sides of the story on utility classes, we can definitely see room for improvement in the way existing frameworks are provided.

To build our own utility framework in SCSS, we’ll stick to the following principles:

To achieve that, we’re going to take advantage of:

%placeholders and @extend.u-, .o-, .c-)Using a small namespace for your class types, you have a structured way to indicate what a class does depending on its type. Most of the frameworks we mentioned earlier do not do this, as they are written to cater for utility only.

We will use namespaces in all of the following examples.

Placeholders are “ghost” definitions made in SCSS to define a style. Their unique feature is that they do not compile unless you reference them somewhere. It’s as if you defined a $variable but never used it.

// Define the placeholder…

%u-display-flex {

display: flex;

}

// This will not compile, until…

.u-flex {

@extend %u-display-flex;

}

// Now we have our utility class ready to use…

.u-flex {

display: flex;

}

Because placeholders won’t show up until we want them to, we can also go ahead and make a placeholder for every breakpoint and state variation on a style.

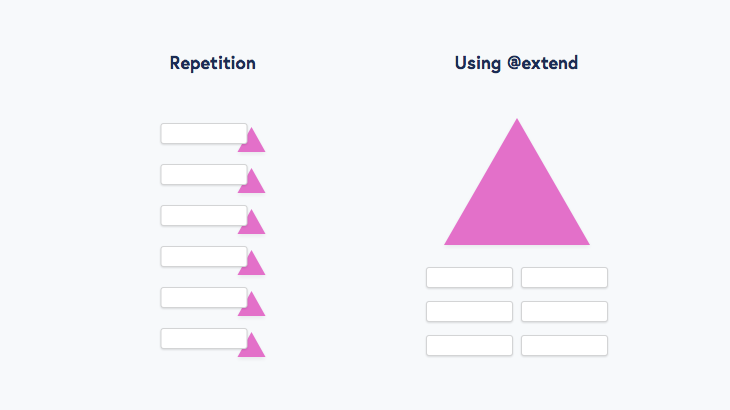

@extend to apply our placeholdersWith our placeholders defined, we can now decide how we want to use them. By using @extend (as opposed to Tailwind CSS’s @apply), we also reduce the amount of repetition in our CSS.

As an example, let’s imagine that lots of our components use a specific border. Our CSS is unnecessarily large if it reads:

.c-sidebar {

border: 1px solid #222;

}

.c-card {

border: 1px solid #222;

}

.c-header {

border: 1px solid #222;

}

When we are consistently using low-specificity classes, we can group these styles together and DRY out the end result:

.c-sidebar {

@extend %border-grey;

}

.c-card {

@extend %border-grey;

}

.c-header {

@extend %border-grey;

}

// Which compiles to…

.c-sidebar,

.c-card,

.c-header {

border: 1px solid #222;

}

Our components can @extend any styles we have in our library, and by referencing a placeholder, we know we’re not creating a wasteful new style definition. Let’s rewrite that messy component example from earlier:

.c-featured-link {

@extend

%u-pos-relative,

%u-padv-3,

%u-padh-4,

%u-bgcolor-blue,

%u-shadow-black-thin,

%u-radius-tlbr-3,

%u-radius-trbl-12,

%u-weight-medium,

%u-size-6rem,

%u-line-thin,

%u-font-europa,

%u-color-light-grey,

%u-whitespace-nowrap;

}

We can also hugely improve the readability of these components by nesting our breakpoints and states.

.c-featured-link {

// …

&:hover,

&:focus {

@extend

%u-top-3,

%u-bg-color-darkblue,

%u-color-white;

}

}

Finally, I’ll walk you through the tools you’ll need in your SCSS to pull off the above. I’m going to describe how they work first so you can rebuild them to your own liking, and then offer a link to a framework that already has the complete set working.

@mixin make-placeholder($utility-name, $properties) {

// No breakpoint

%#{$utility-name} {

@each $property, $value in $properties {

#{$property}: $value;

}

}

// Every breakpoint

@each $breakpoint-key, $breakpoint-value in $global-breakpoints {

%#{$utility-name + $global-breakpoint-separator + $breakpoint-key} {

@include breakpoint($breakpoint-key) {

@each $property, $value in $properties {

#{$property}: $value;

}

}

}

}

}

The mixin above first creates a placeholder for each property sent in the $properties argument. Then, we loop through all the breakpoints we’ve defined elsewhere in the $global-breakpoints map to ensure we have breakpoint placeholders, too.

This will provide us with placeholders as follows:

@media (min-width: 600px) {

%u-bgcolor-primary\@medium {

background-color: blue;

}

}

We escape the @ symbol (our breakpoint and state identifier) as it’s an invalid character; you’re welcome to choose your own separator character to replace it.

@mixin make-class-from-placeholder($utility-name, $properties) {

.#{$utility-name} {

@extend %#{$utility-name};

}

}

As we need to (in the next mixin), create a utility class directly from our new %placeholder.

@mixin make-utility($args) {

$class: map-use(

$args,

class,

false

);

$args: map-remove($args, class);

// If 'alias' key exists in $args, use that for the placeholder-name,

// otherwise use the key and value of the first property in $args

$utility-name: map-use(

$args,

alias,

first(map-keys($args)) + '-' + first(map-values($args))

);

$utility-name: 'u-' + $utility-name;

$properties: map-remove($args, alias);

@include make-placeholder($utility-name, $properties);

@if ($class) {

@include make-class-from-placeholder($utility-name, $properties);

}

}

The last step is to support aliases, which allows you to decide if you prefer to go letter for letter in your class names (justify-content-space-between) or if you prefer a tiny shortcut (jc-sb).

It’s completely up to you — the longer name means that any developer can jump in and will know the pattern immediately, but the shorter name is easier to scan for and faster to type.

With the alias decided (or left blank), we then check if you want to use Make Class and complete the placeholder.

To get the most our of our placeholder-building, you’ll want to list properties and values to add to your library.

Here are a few helpful loops to get you on your way:

@each $wrap in (nowrap, wrap, wrap-reverse) {

@include make-utility((

alias: 'fw-' + $wrap,

flex-wrap: $wrap

));

}

@each $property in (translateX, translateY) {

@each $value in (-100, -50, 0, 50, 100) {

@include make-utility((

alias: $property + '-' + $value + $global-unit-percent,

transform: $property + '(' + $value + '%)'

));

}

}

@each $property in (margin-top, margin-right, margin-bottom, margin-left) {

@for $value from 1 through 30 {

@include make-utility((

$property: #{$value + 'rem'};

));

}

}

If you’d like to quick-start your own framework, you can grab the latest version of stemCSS.

Recent tools and frameworks have rocketed the idea of utility classes into the mainstream, and they are reaping the benefits of their exceptional documentation (hat-tip to Tailwind CSS). It’s clear that utility classes have shifted the landscape for how developers use low-specificity CSS classes as a methodology for consistent styling.

What will the future of stylesheets throw at us next?

As web frontends get increasingly complex, resource-greedy features demand more and more from the browser. If you’re interested in monitoring and tracking client-side CPU usage, memory usage, and more for all of your users in production, try LogRocket.

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork around why bugs happen by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings — compatible with all frameworks.

LogRocket's Galileo AI watches sessions for you, instantly identifying and explaining user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

Modernize how you debug web and mobile apps — start monitoring for free.

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

A breakdown of the wrapper and container CSS classes, how they’re used in real-world code, and when it makes sense to use one over the other.

This guide walks you through creating a web UI for an AI agent that browses, clicks, and extracts info from websites powered by Stagehand and Gemini.

This guide explores how to use Anthropic’s Claude 4 models, including Opus 4 and Sonnet 4, to build AI-powered applications.

Which AI frontend dev tool reigns supreme in July 2025? Check out our power rankings and use our interactive comparison tool to find out.

3 Replies to "CSS utility classes: Your library of extendable styles"

See no reason to invent utility classes, tailwind done it right and easy to use anywhere.

By your logic Tailwind wouldn’t exist, because Tachyons already ‘did it right’ 🙂

Hello Russel,

Your second bullet point within the StemCSS list (Further reading: “On Moving to a Utility-first CSS Framework,” by Debra Ohayon) points to an article on TailwindCSS. I thought I would let you know.

Cheers!