If you do any type of frontend web development today, animation is likely part of your daily work, or at least the project that you’re working on. Animation in JavaScript has come very far in recent years, from animating text or an image to full-fledged 3D animation with tools like WebGL.

There are a lot of JavaScript frameworks that provide animation functionality. There are also several libraries that work with the canvas and WebGL to create interactive experiences.

In this post, I’m going to do a comparison of four different JavaScript animation libraries. The libraries I’m listing here are by no means the only options, but hopefully, they’ll show you patterns that you can follow when adding any animation to your projects.

For this post, we’ll look at the following:

I’ll cover implementations with a React project, but you should be able to follow similar patterns for any frontend framework (or vanilla JavaScript as well). You can view the project I built here. I’ve also built components for examples with each of the libraries, which you can be see here.

In the next sections, I’ll discuss how to use each of the above libraries. I’m going to cover basics and their implementation in a React project. I’ll also offer some pros and cons that I found when working with them.

This post assumes some familiarity with React and JavaScript projects. All the libraries I discuss can be applied to any JavaScript framework, it’s just a matter of correctly importing the library and calling the APIs discussed.

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

Anime.js provides a basic API that lets you animate almost anything you can think of. With Anime.js, you can do basic animations where you move objects back and forth, or you can do more advanced animations where you restyle a component with an action.

Anime.js also offers support for things like timelines, where you can create an animated sequence of events. This is particularly useful when it comes to presenting several events at once.

To use Anime.js, you first have to install it through either npm install or download it directly from the GitHub project here.

Since the example project is based on React, I’m using npm:

npm install animejs --save

Once you’ve got it installed, you can import it into your component with standard JavaScript imports:

import anime from "animejs";

Once imported, you can define animations with the anime object:

anime({

targets: ".anime__label",

translateX: "250px",

rotate: "1turn",

backgroundColor: "#FFC0CB",

duration: 800,

direction: "alternate"

});

Anime.js always requires a “target,” as you see here. Targets can include anything that you use to identify DOM elements. In this case, I’ve identified elements that contain the .container__label class.

Beyond defining your target, you also typically define CSS properties — in this case, I’ve defined a backgroundColor.

You also define “Property Parameters” and “Animation Parameters,” as I have done in this example with:

translateXrotatedurationdirectionSo if you define the animation like I have above, you are saying the following:

.container__label class elements to move to the right 250px#FFC0CBdirection: "``alternate``")Putting it all together, it should look like this:

Now if you want to animate multiple objects, you can connect the animations together with a timeline. The process for this is just to define a timeline, and then add additional animations like the following (this example was copied from the Anime.js docs):

const tl = anime.timeline({

easing: 'easeOutExpo',

duration: 800,

direction: "alternate"

});

tl

.add({

targets: '.anime__timeline--pink',

translateX: 250,

})

.add({

targets: '.anime__timeline--blue',

translateX: 250,

})

.add({

targets: '.anime__timeline--yellow',

translateX: 250,

});

So what this does is define an initial animation event that uses easing (movement behavior) that lasts for 800ms and alternates just like the text animation.

Then, with the .add methods, we add additional animations specific to elements that have the .anime__timeline--pink, .anime__timeline--blue, and .anime__timeline--yellow classes.

The resulting behavior looks like the following:

For a complete copy of the code for these elements, please look at the animejs component here.

These two examples just scratch the surface of what Anime.js can do for your projects. There are multiple examples in their docs here. Additionally, there are a lot of great examples available on codepen here.

Pros:

Cons:

Ultimately, I really liked Anime.js, except that I would definitely recommend adding more documentation. Also, since the animations required selectors, it made it a little difficult at times to translate elements styling to what I wanted animated.

The p5.js library is an interpretation of the original Processing project started by Casey Reas and Ben Fry at MIT. Processing included an editor and language that attempted to make visual designs easier for artists and creators.

The original project was supported in multiple languages, and made creating visual elements much easier than other basic libraries like Java’s Swing, for example. p5.js brings these concepts to JavaScript and enables you to quickly build out animations with the HTML canvas. p5.js also lets you create 3D images and audio.

To get started, you can either directly download the p5.js library or install it with npm:

npm i p5

Wherever you want to use p5.js, you create animations as a “sketch” object.

The setup method enables you to initiate your canvas object and apply any sizing, etc. The draw method lets you apply any recurring behavior to the page as your canvas refreshes.

If you look to the Get Started page for p5.js, they define a simple example (with an animation) as the following:

function setup() {

createCanvas(640, 480);

}

function draw() {

if (mouseIsPressed) {

fill("#000000");

} else {

fill("#FFFFFF");

}

ellipse(mouseX, mouseY, 80, 80);

}

In setup above, the call to createCanvas creates a canvas that is 640x480px.

Then, the draw method adds an event listener for the mouseIsPressed event to apply a fill property based on whether the mouse is clicked. This fill property is basically applying the color specified in the parentheses (in our case, it’s black when pressed and white when not pressed).

Then, the ellipse method is called to draw an ellipse on the screen. Since this method is called whenever the canvas pages or refreshes, it creates an animation effect of drawing circles on the screen.

Since in our example application we are using React, this is a little different. In React, we just have to reference the p5 library and then append a sketch to the DOM that is returned, as you can see here:

import React, { Component } from "react";

import "./../styles/_title.scss";

import p5 from 'p5';

class P5WithSketch extends Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props)

this.myRef = React.createRef()

}

Sketch = (p) => {

let x = 100;

let y = 100;

p.setup = () => {

p.createCanvas(640, 480);

}

p.draw = () => {

if (p.mouseIsPressed) {

p.fill("#000000");

} else {

p.fill("#FFFFFF");

}

p.ellipse(p.mouseX, p.mouseY, 80, 80);

}

}

componentDidMount() {

this.myP5 = new p5(this.Sketch, this.myRef.current);

}

render() {

return (

<div>

<section className="title">

<a

className="title__heading"

href="https://p5js.org/"

>

P5.js

</a>

</section>

<section ref={this.myRef}>

</section>

</div>

);

}

}

export default P5WithSketch;

The final animation that is created looks like the following:

This is just the start of what you could do with p5.js. You can easily extend the basic animation here to react to user input as well as render full 3D elements. There are a lot of really great examples of p5.js sketches that showcase this behavior. Check out their example page here for more info.

The full working component in my sample project can be found here.

Pros:

Cons:

The Green Sock Animation Platform (GSAP) provides a fairly robust library that has animations for almost any type of effect your project could need. Additionally, they have really strong documentation that includes examples of how to interact with their APIs.

To get started with GSAP, you first just need to install it as a dependency to your project:

npm i gsap

Once you’ve loaded it into your project, then it’s just a matter of defining animation behavior with the gsap object, like you see here:

animateText = () => {

gsap.to(".gsap__label", { duration: 3, rotation: 360, scale: 0.5 });

};

animateSquare = () => {

gsap.to(".gsap__square", { duration: 2, x: 200, ease: "bounce" });

};

When working with GSAP, you’ll often notice the docs refer to animations as “tweens,” which is similar to the way we saw p5.js refer to animations as “sketches.”

When using GSAP, you use to and from methods to indicate start and stop behaviors. In the case of the two examples I’ve put here, they are applying animations to elements that have the .container__label and .container__square style.

Similar to the way we worked with Anime.js, GSAP offers properties like duration, rotation, ease, and scale.

When applied to a template, the above example looks like the following:

Similar to Anime.js, there are a lot of cool things you can do with GSAP. You can also do timelines and other sequenced animations. For a more in-depth walkthrough, check out the Getting Started with GSAP page. For a full list of examples, you can check out the GSAP CodePen page.

A full working copy of the component that I’ve covered is in my sample project here.

Pros:

Cons:

Up until this point, all of the animations have either interacted directly with DOM elements or added custom elements. The Three.js library uses WebGL to render animations.

What is WebGL? WebGL is a DOM API that enables you to render graphics in the browser. It does use the canvas element, but rather than generating a canvas and writing on top of it, as we saw with p5.js, WebGL allows you to call APIs to do the rendering for you.

Three.js is a library that orchestrates the WebGL calls in order to render images and graphics within the browser. This is really great if you want to create an animation or 3D graphic associated with your project.

Three.js has a great walkthrough sample project that can be reached here. As I mentioned, my sample project is using React, so the setup is slightly different. The core concepts and API calls are all the same.

If you have any issues with understanding (or getting the example to work), I recommend reviewing the explanation in the Three.js documentation here.

To get this working is a multistep process. We must first define the renderer to use for our animation:

const scene = new THREE.Scene();

let camera = new THREE.PerspectiveCamera(75, 400 / 400, 0.1, 1000);

const renderer = new THREE.WebGLRenderer();

renderer.setSize(400, 400);

this.mount.appendChild(renderer.domElement);

Three.js calls this “creating a scene.” The long and short of it is basically creating the area for the animation to occur.

Next we define objects we want to animate:

const geometry = new THREE.BoxGeometry(1, 1, 1);

const material = new THREE.MeshNormalMaterial();

const cube = new THREE.Mesh(geometry, material);

scene.add(cube);

Here, we’re using Three.js global objects to define the cube and material associated with it for animation.

Next, we define the animation method:

camera.position.z = 5;

const animate = function () {

requestAnimationFrame(animate);

cube.rotation.x += 0.01;

cube.rotation.y += 0.01;

renderer.render(scene, camera);

};

This is what will be called, and how Three.js calls the WebGL API methods to show the animation.

Finally, we call the animate method directly to render the animation:

animate();

To get all this working with React, we just put it in the componentDidMount lifecycle method of the component we want to show:

componentDidMount() {

// create the scene and renderer for the animation

const scene = new THREE.Scene();

let camera = new THREE.PerspectiveCamera(75, 400 / 400, 0.1, 1000);

const renderer = new THREE.WebGLRenderer();

renderer.setSize(400, 400);

this.mount.appendChild(renderer.domElement);

// create the elements that become a rotating cube and add them to the scene

const geometry = new THREE.BoxGeometry(1, 1, 1);

const material = new THREE.MeshNormalMaterial();

const cube = new THREE.Mesh(geometry, material);

scene.add(cube);

// create the actual animation function that will draw the animation with WebGL

camera.position.z = 5;

const animate = function () {

requestAnimationFrame(animate);

cube.rotation.x += 0.01;

cube.rotation.y += 0.01;

renderer.render(scene, camera);

};

// call the animation function to show the rotating cube on the page

animate();

}

The resulting animation looks like the following:

There are a lot of cool things you can do with Three.js. I recommend checking out their docs here and examples here.

A full working copy of the component I’ve covered is available in my sample project here.

Pros:

Cons:

I hope this post gave you a basic look at some different JavaScript animation libraries that are available today.

I wanted to note some commonalities between the four libraries I covered.

With Anime.js and GSAP, they both accomplished animations by importing a global object, identifying elements to apply animations to, and then defining the animation, like so:

// anime.js

anime({

targets: ".anime__label",

translateX: "250px",

rotate: "1turn",

backgroundColor: "#FFC0CB",

duration: 800,

direction: "alternate"

});

// GSAP

gsap.to(".gsap__label", { duration: 3, rotation: 360, scale: 0.5 });

With p5.js and Three.js, custom elements were created and appended to the DOM. Both leveraged an HTML canvas to generate the associated animation, like so:

// P5.js

Sketch = (p) => {

let x = 100;

let y = 100;

p.setup = () => {

p.createCanvas(640, 480);

}

p.draw = () => {

if (p.mouseIsPressed) {

p.fill("#000000");

} else {

p.fill("#FFFFFF");

}

p.ellipse(p.mouseX, p.mouseY, 80, 80);

}

}

// Three.js

const scene = new THREE.Scene();

let camera = new THREE.PerspectiveCamera(75, 400 / 400, 0.1, 1000);

const renderer = new THREE.WebGLRenderer();

renderer.setSize(400, 400);

this.mount.appendChild(renderer.domElement);

Seeing these common behaviors gives you an idea of what you could expect with any JavaScript animation library. As I stated in the intro, while this post covered these four libraries specifically, there are still many others that are available to you today.

The best part is that with the advances in both web development and browser technologies, JavaScript animations can do much more than ever before. I encourage you to review the documentation associated with the libraries covered here for more info.

Thanks for reading my post! Follow me on Twitter at @AndrewEvans0102!

Debugging code is always a tedious task. But the more you understand your errors, the easier it is to fix them.

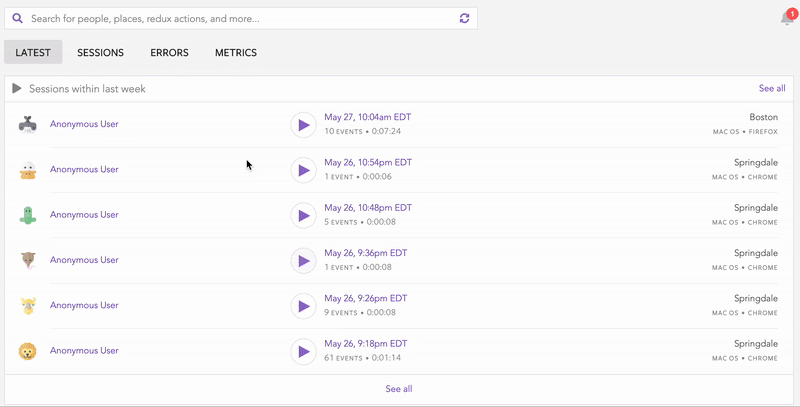

LogRocket allows you to understand these errors in new and unique ways. Our frontend monitoring solution tracks user engagement with your JavaScript frontends to give you the ability to see exactly what the user did that led to an error.

LogRocket records console logs, page load times, stack traces, slow network requests/responses with headers + bodies, browser metadata, and custom logs. Understanding the impact of your JavaScript code will never be easier!

Solve coordination problems in Islands architecture using event-driven patterns instead of localStorage polling.

Signal Forms in Angular 21 replace FormGroup pain and ControlValueAccessor complexity with a cleaner, reactive model built on signals.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the February 25th issue.

Explore how the Universal Commerce Protocol (UCP) allows AI agents to connect with merchants, handle checkout sessions, and securely process payments in real-world e-commerce flows.

Would you be interested in joining LogRocket's developer community?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

4 Replies to "Comparing JavaScript animation libraries"

Elephant in the room question: Why did you exclude `D3` in your review? Just curious.

I’d say that three.js & p5.js are in completely different ballpark. Even three.js is used most of the time in conjunction with tween.js (animating/tweeting library that’s not even mentioned here).

Although, it’s good rundown with comprehensive information and example code. I just find the title misleading.

Interesting article

One must refer this article before starting with creating the animations using Javascript.