In a previous blog post with LogRocket, I covered the RGB and HSL color models and how to manipulate their various color properties. One aspect that I did not have the chance to cover was some of the upcoming models coming to CSS. This post will overview all of the color models, new and old, that will be a part of the CSS Color Module Level 4, their properties, and when they might be useful.

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

RGB is the original color model to be part of CSS. An initialism for red, green, blue, the RGB model is an additive color model, which means the system works by adding colored lights together to make new colors.

For example, a “pure” red would have a red value of 100% and green and blue values of 0%. A “pure” yellow would have red and green values of 100% and a blue value of 0%. In CSS, the RGB notation can be conveyed with either the rgb() color function or the hexadecimal notation: red would be rgb(255 0 0) or #ff0000, respectively.

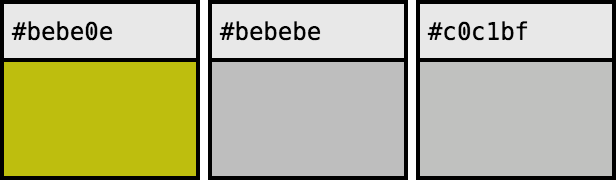

You can make a few inferences about a color before ever seeing it by reading its RGB components. For example, if the individual components are all equal, then you know the color is grayscale. The higher all the numbers are, the brighter the overall color is; conversely, the lower the numbers are, the darker the color is.

There are some advantages to the RGB color model. Perhaps the biggest among them is how ubiquitous it is as a color notation. The hexadecimal notation especially is used in many design tools. Another possible advantage is that the RGB model is similar to how the computer “thinks” about color: the monitor combines different colored lights to display the colors.

There are some disadvantages to RGB as well. For one, it is not a very legible system. Especially in the hexadecimal and “byte” size notations (#ffffff and rgb(255, 255, 255), respectively), the format is designed for computers more than for humans. The relationship between colors is especially difficult; it may be hard to see at a glance that #bebebe is almost identical to #c0c1bf but is drastically different from #bebe0e.

When does it make sense to use RGB? When you want to manipulate a color programmatically in real time, for example. You can manipulate an HTML5 canvas’s ImageData object by reading and manipulating its pixels in RGB. Since this is how the canvas shares its color information, it may make sense to stay “close to the metal” when manipulating it programmatically, especially since costly functions will multiply quickly on large images or video.

Another reason you might want to use RGB is if you are working on a large team that uses multiple design tools and platforms. Due to RGB’s ubiquity, it may make sense to use it for consistency’s sake.

The HSL color functions were added in CSS3. Standing for hue, saturation, lightness, it is designed to give a more intuitive mental model.

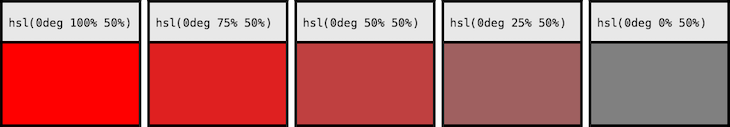

The hue value corresponds to the position of the color on the color wheel and is represented as an angle (usually degrees). The saturation value is a percentage that refers to the intensity of a color. The lightness value is a percentage that refers to how bright the color is. In CSS, a red would be portrayed as hsl(0deg, 100%, 50%).

Compared to RGB, HSL is a much more intuitive model, especially when dealing with the manipulation of colors. If you would like to brighten or desaturate a hue, you need only update a single number. The relationship between colors becomes much easier to see.

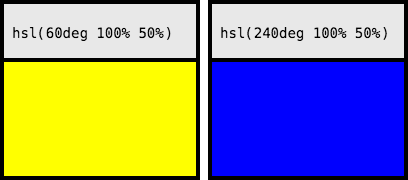

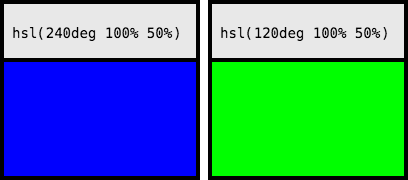

One of the biggest problems with HSL is how it deals with lightness. The HSL lightness is relative to its base color rather than as an absolute value. For example, a pure yellow (hsl(60deg, 100%, 50%)) and a pure blue (hsl(240deg, 100%, 50%)) both have a lightness of 50 percent, despite the blue appearing to be much less bright.

If we look at the same two colors notated in RGB — rgb(100%, 100%, 0) and rgb(0%, 0%, 100%), respectively — we notice that the yellow has twice as much physical light being emitted, as both the red and green channels are at 100 percent.

In addition to some hues physically emitting more light than others, there is another quirk that needs to be considered: human eyes don’t view all wavelengths as equally bright. For example, green and blue both emit the same amount of light, but the human eye perceives the green as being brighter than the blue.

Later in this post, I’ll cover an alternative to the HSL lightness.

Since HSL is already available to use as of CSS3, and it’s more intuitive when compared to RGB, I find that it is the best currently available solution for many web projects. When creating and viewing color palettes for design systems, the HSL model allows for much easier manipulation of colors. Although it is not perfect in how it treats lightness, HSL strikes a good balance between simplicity and usefulness.

Now, let’s take a look at some of the models coming in the CSS Color Module Level 4! First up is the color model HWB. HWB, an initialism for hue, whiteness, blackness, is a color model that was introduced by Alvy Ray Smith, a pioneer in computer animation and one of the co-founders of Pixar.

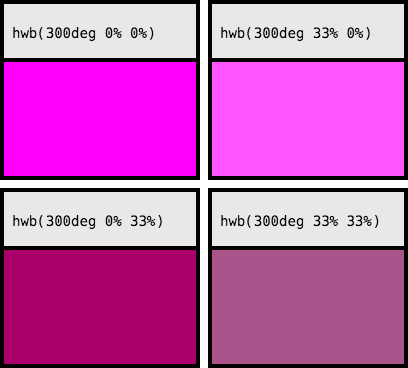

Created as an alternative to HSL (and HSV, which is not mentioned elsewhere in this article since it is not currently being considered for implementation in CSS), the HWB color model was created for its simplicity. In Smith’s words, all you need to do is: “Choose a hue. Lighten it with white. Darken it with black.”

The hue in HWB is identical to HSL. The whiteness and blackness attributes are both specified as percentages. To lighten a hue, increase the whiteness; to darken it, increase the blackness. To desaturate a color, increase both the whiteness and blackness.

If the two percentages add up to more than 100 percent, it is a shade of gray, and the two attributes are normalized to add up to exactly 100 percent. For example, a shade of hwb(0deg 75% 75%) is identical to hwb(0deg 50% 50%). A shade of hwb(0deg 25% 100%) is normalized to hwb(0deg 20% 80%).

If the normalized whiteness is 100 percent (and therefore the normalized blackness is 0), the color is a pure white. Conversely, a normalized blackness of 100 percent is a pure black.

Where might you use HWB? Because of its intuitiveness, the HWB color model works well for user-inputted colors. Since the concept of HWB is similar to mixing paint, non-technical users can understand it.

We discussed the problems with the HSL version of lightness. The alternative is to use models that use the International Commission on Illumination (CIE) scale of lightness. It differs from the HSL model in two ways.

First, whereas the HSL lightness is relative to its base color, the CIE lightness is an absolute model. This means the CIE lightness is based around the total amount of light being emitted. Secondly, CIE lightness adjusts for the fact that human eyes don’t perceive all colors equally. Together, this means that the CIE lightness is perceived equally between different hues.

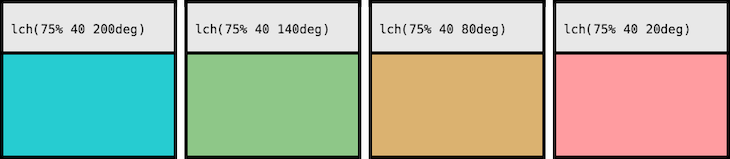

LCH is one of the color models that uses CIE lightness. It stands for lightness, chroma, hue. Chroma is related to saturation, but is subtly different.

The CIE’s definition of chroma is “colourfulness of an area judged as a proportion of the brightness of a similarly illuminated area that appears white or highly transmitting.” This is portrayed as a number. As per the CSS spec, this value is “theoretically unbounded (but in practice does not exceed 230).”

The hue in LCH is similar to that in HSL, but in a perceptually uniform space. If you compare sampling of a color wheel from HSL to LCH, you’ll notice that certain colors are over-sampled in the HSL wheel.

What are the advantages of the LCH system? The short answer is if you like the HSL color system but want to use a model that has a more uniform lightness, LCH is a good pick for you.

Another model that uses CIE lightness is the Lab color space. The L stands for the CIE lightness. The a and b are two color channels: a represents a green-to-red axis, and b represents a blue-to-yellow axis. Both values are numbers that can be either positive or negative. If both values are 0, the color is a shade of gray.

I personally find the cylindrical representation of LCH to be more intuitive to that of Lab, and therefore, I can’t think of any reasons that you might choose Lab over LCH. If you have any thoughts or ideas, please add your comment below!

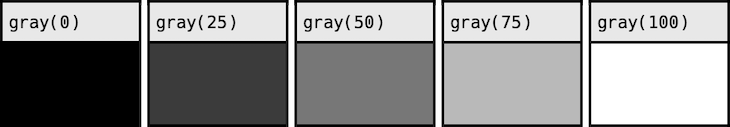

gray()There is another functional notation that is used specifically to notate shades of gray. The gray() functional notation accepts only a CIE lightness parameter. This notation is equivalent to Lab with both the a and b parameters set to 0.

You might want to use the gray() notation if your primary color model is Lab or LCH but you would like to explicitly signal in your code that the color is a shade of gray.

There is one color model that is slightly different than the rest. While all the other colors that we have talked about so far were designed to be used on screens, this next color model is made primarily for use with printers.

The model is CMYK, which stands for cyan, magenta, yellow, and key (black). The CMYK model is best understood when compared to RGB: just like RGB is an additive model, CMYK is a subtractive model. RGB works by adding light, and CMYK works by subtracting light — that is, adding pigments that absorb additional light.

Since CMYK is designed for printers, it is a device-dependent color model. This means that when converting between CMYK and RGB colors, the results may differ depending on the physical characteristics of the device. If the browser is provided a color profile, it will be used for a conversion. Otherwise, there is a “naive” conversion that is used.

In addition, you can provide a fallback to the device-cmyk() color function that will be used if there is no color profile. Because of these difficulties, the W3C Editor Draft says that “it’s recommended that if authors use any CMYK colors in their document, that they use only CMYK colors in their document to avoid any color-matching difficulties.”

When might you want to use the CMYK color model? This is pretty straightforward: CMYK is useful if you are creating a print stylesheet. Otherwise, the other color models will likely be a better choice.

Each of these color models brings something new to CSS: CMYK gives a printer-focused model; Lab, LCH, and gray() provide a more consistent lightness property; and the HWB brings an incredibly intuitive interface. The future of colors in CSS is bright.

As web frontends get increasingly complex, resource-greedy features demand more and more from the browser. If you’re interested in monitoring and tracking client-side CPU usage, memory usage, and more for all of your users in production, try LogRocket.

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork around why bugs happen by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings — compatible with all frameworks.

LogRocket's Galileo AI watches sessions for you, instantly identifying and explaining user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

Modernize how you debug web and mobile apps — start monitoring for free.

Discover five practical ways to scale knowledge sharing across engineering teams and reduce onboarding time, bottlenecks, and lost context.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the March 4th issue.

Paige, Jack, Paul, and Noel dig into the biggest shifts reshaping web development right now, from OpenClaw’s foundation move to AI-powered browsers and the growing mental load of agent-driven workflows.

Check out alternatives to the Headless UI library to find unstyled components to optimize your website’s performance without compromising your design.

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now