Navigation bars are probably the best way to allow users navigate around your websites effortlessly without getting lost.

People usually place navbars at the very top of the page, but you can also put a navbar on either side of your webpage if it compliments your design. Navbars can either be a horizontal list of nav items or hamburger-style at the top-left or top-right corners of webpages on smaller screens.

To allow better accessibility to navbars, you can sticky them at the top by using a few lines of CSS and JavaScript. More JavaScript code can become piled up as the complexity of the navbar increases.

In this post, we’ll see how you can create a custom sticky navbar that is responsive to all screen sizes with great functionality, using only CSS to create it. We’ll also learn how to use the SCSS’s syntactic sugar to write our CSS code much faster and cleaner.

Here is the demo of what we will be building!

So, let’s get started.

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

We’ll start with some simple stuff and gradually dive into more complex things as this article shall progress. The first thing we can do to create a nav bar is, write some HTML. So, start by copying this HTML code into your favorite code editor or in a Codepen.

<html>

<body>

<header class="header">

<nav class="header__nav" id="navbar">

<ul class="header__list">

<li class="header__item"><a href="index.html" class="header__link">Home</a></li>

<li class="header__item"><a href="about.html" class="header__link">About</a></li>

<li class="header__item"><a href="services.html" class="header__link">Services</a></li>

<li class="header__item"><a href="services.html" class="header__link">Contact</a></li>

</ul>

</nav>

</header>

</body>

</html>

The above-given HTML code is quite simple, and there’s nothing complex going on in it. I’d like you to note the conventions I used for writing the class names for every element. This little convention to write class names for HTML elements is known as BEM, which stands for Block, Element-, Modifier.

We give a block name to every wrapper element in our HTML code. In this case, the wrapper is our <header class="header">. You can also describe it as the parent element.

Each child element inside the wrapper or parent has the class name of its parent, followed by two underscores with a unique identifier. As you may have noticed, in our case, it’s:

<nav class="header__nav" id="navbar">

Now, we can give every child element in our wrapper a class name like this. Another thing to note here is that I have started their class names with the word header, even when they are the sub-child of the header. It is done on purpose to maintain consistency, and while writing SCSS code, it will eventually help us a lot. We’ll see this in a bit.

To proceed, you can copy the below given SCSS code in your SCSS file:

$color-blue: #00315c;

$color-purple: #6f479f;

$color-black: #202020;

$color-gray: #edebeb;

$color-white: #fcfcfc;

html {

font-size: 62.5%;

scroll-behavior: smooth;

}

html,

body {

width: 100%;

margin: 0px;

padding: 0px;

overflow-x: hidden;

}

body {

font-family: "Montserrat", sans-serif;

}

.header {

height: 20vh;

background-color: $color-gray;

padding: 1.5rem;

position: relative;

&__nav {

display: flex;

position: fixed;

top: 0;

left: 50%;

transform: translateX(-50%);

padding: 4rem 5rem;

justify-content: space-around;

align-items: center;

z-index: 100;

width: 100%;

transition: 0.6s;

}

&__list {

list-style: none;

display: flex;

}

&__item {

&:not(:last-child) {

margin-right: 5rem;

}

}

&__link {

font-size: 1.6rem;

color: $color-blue;

font-weight: 400;

text-decoration: none;

&:hover {

font-weight: 600;

transition: all 0.3s;

}

}

}

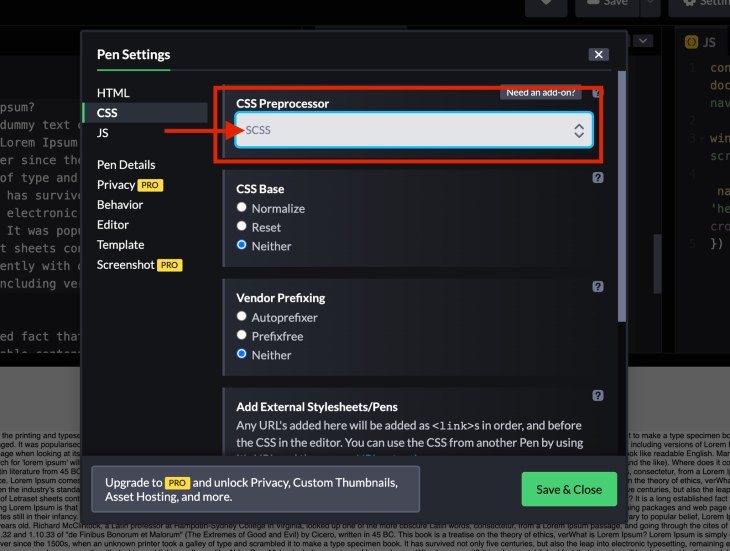

(Note: If you’re following along with me in Codepen, you can select the SCSS option in the settings menu in the CSS window. If you’re in an editor like VS Code, you can download the SCSS extension; it will compile your SCSS code into CSS code, which you can include in your HTML file)

If you are familiar with SCSS and understand what is going on in the above code, then feel free to skip the next few paragraphs.

The first few lines of code are the variables for the colors, which we’ll be using most in this tutorial. You can set these variables to any color you like, and then instead of writing the hash value or RGBA value every time you want to use a color, you can write the variable name.

The syntax that I want you to note starts from line 24. I have written the .header to initiate the styling for the header element. But, inside the same brackets, I have also written &__nav, which initiates the styling for our nav element.

In SCSS, you can write the styling of the nested elements in the same brackets. In addition, the & sign holds the value of your parent identifier. In this case, it’s .header If we were using IDs instead of class names, the & would mean #header

You can also see, in line 61, how I have used the &:hover because I wanted to apply the pseudo-hover class on my link elements. So, this makes it easy for us to write the nested styling and remove the redundant code. If you’d like, you can read more about SCSS and its syntax.

As you may have noticed, we didn’t put much effort into creating a navbar for larger screens because, as per good user experience, it should always be a horizontal list at the top of the screen. We can add the hamburger menu on larger screens, but to prevent extra clicks from users, the hamburger menu always goes on smaller screens, which we’ll be doing now.

Now, we can move our focus on creating a custom hamburger navbar on smaller screens by just using CSS.

To give you an overview of what we are building; it is not feasible to display horizontal nav items on smaller screens. Instead, we’ll create a hamburger menu, which will display the items by overlaying the background of the whole screen.

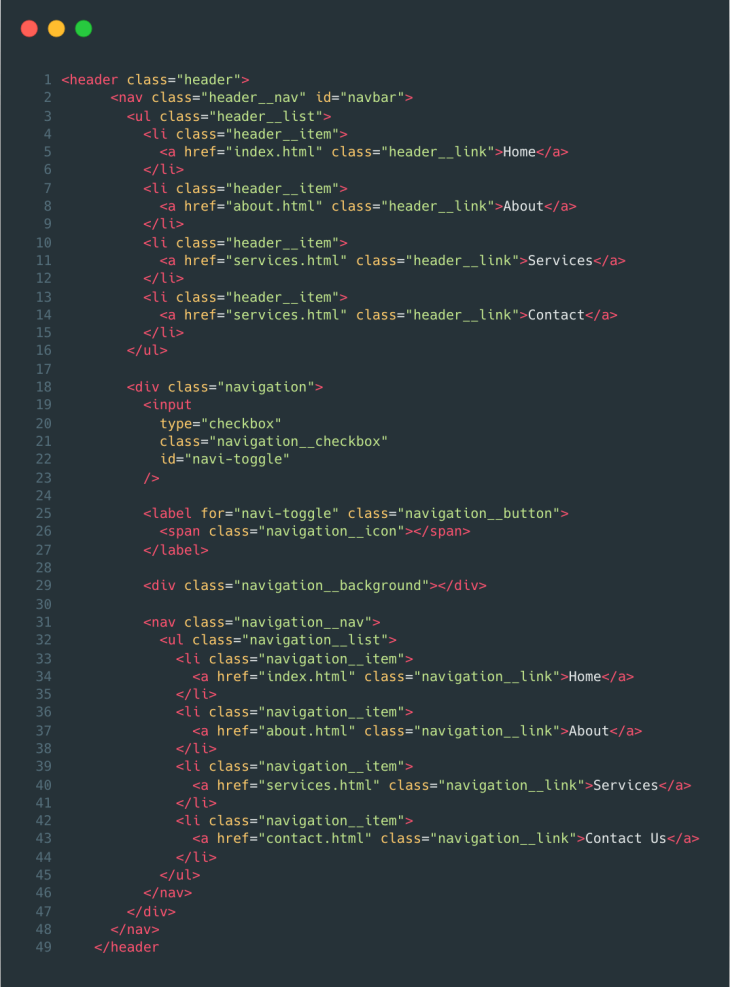

Let’s get started by writing some code. Copy the below HTML code after line 10 inside your existing HTML code.

<div class="navigation">

<input

type="checkbox"

class="navigation__checkbox"

id="navi-toggle"

/>

<label for="navi-toggle" class="navigation__button">

<span class="navigation__icon"></span>

</label>

<div class="navigation__background"></div>

<nav class="navigation__nav">

<ul class="navigation__list">

<li class="navigation__item">

<a href="index.html" class="navigation__link">Home</a>

</li>

<li class="navigation__item">

<a href="about.html" class="navigation__link">About</a>

</li>

<li class="navigation__item">

<a href="services.html" class="navigation__link">Services</a>

</li>

<li class="navigation__item">

<a href="contact.html" class="navigation__link">Contact Us</a>

</li>

</ul>

</nav>

</div>

After copying the code, your HTML file should look something like this:

It is the only HTML code we need to make a hamburger menu that looks good on smaller screens. So, let me explain to you some key points in this newly added code:

<div> element and given that <div> a class name of navigation. Inside the div, we have added a checkbox. This checkbox will help us to determine when we want our nav items to show and when we want to hide them<div> with a class name navigation__background. This div will provide a background overlay for our nav items to be displayed clearly on the screenN.B., I have used the same BEM naming conventions for writing class names for every element.

Now, all that is left is styling our navigation bar. So, we’ll be writing a lot of CSS code. I’ll try to explain each block of CSS we write one by one so that it does not cause any confusion.

Firstly, we’ll write some media queries because we need to display the hamburger menu at a certain width. For media queries, we’ll be using SCSS mixins, which are essentially functions.

For the argument, you will pass the breakpoint on which you want to see the changes. To make things easier, you can give each breakpoint a name of its own; for example, 400px can be named “phone” because that’s the average screen width of a phone.

Once called, you can write your CSS styles inside the curly brackets, and the styles will be applied to that breakpoint. Let’s see how we can achieve this by writing those media queries.

Copy the following code at the top of your SCSS file, and we’ll be ready to use these media queries.

@mixin respond($breakpoint) {

@if $breakpoint == phone {

@media only screen and (max-width: 37.5em) {

@content;

} //600px

}

@if $breakpoint == s-hundred {

@media only screen and (max-width: 43.75em) {

@content;

} //700px

}

@if $breakpoint == tab-port {

@media only screen and (max-width: 56.25em) {

@content;

} //900px

}

@if $breakpoint == tab-land {

@media only screen and (max-width: 75em) {

@content;

} //1200px

}

@if $breakpoint == big-desktop {

@media only screen and (min-width: 112.5em) {

@content;

} //1800

}

}

Did you get the syntax for these media queries? We created a mixin named respond, which takes any breakpoint as the argument and applies those styles within that media query.

Now, we can start styling our navigation bar based on these media queries. So, let’s start by copying this code:

.navigation {

display: none;

@include respond(s-hundred){

display: block;

}

z-index: 2000;

&__checkbox {

display: none;

}

}

In the above code, we are setting the display of our hamburger navigation to none because we only want to be visible on smaller screens. So, we have used our respond mixin to attain that functionality.

The z-index is set to 2000 because we want our navigation bar to overlay all the other content. We’ll get to see it later in this article.

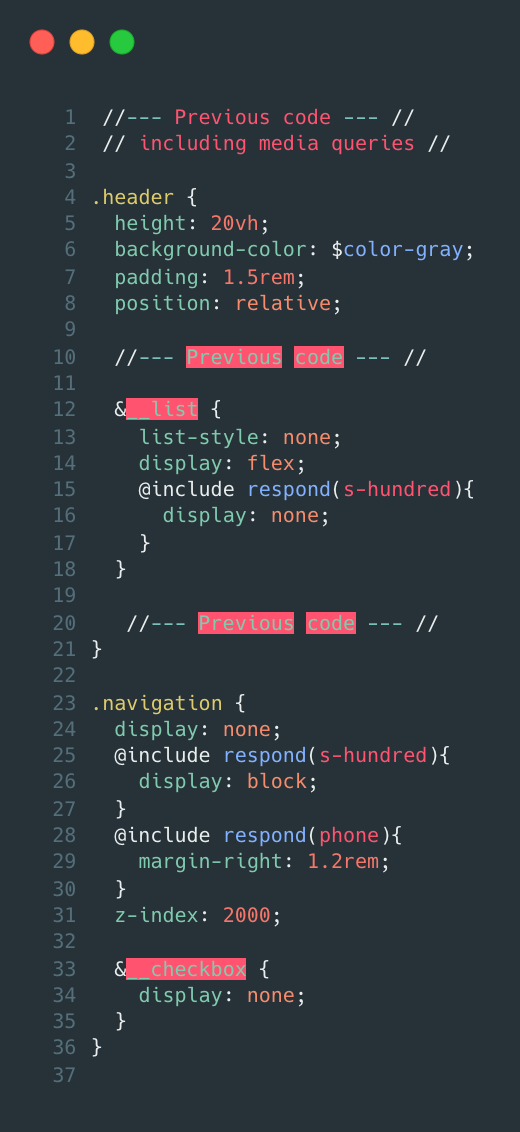

Since we are displaying our hamburger navigation at 700px, we can remove the display of our horizontal list at the same width. To do this, add this little highlighted media query inside your header__list style:

&__list {

list-style: none;

display: flex;

@include respond(s-hundred){

display: none;

}

}

After adding these code blocks, your SCSS file should look like this:

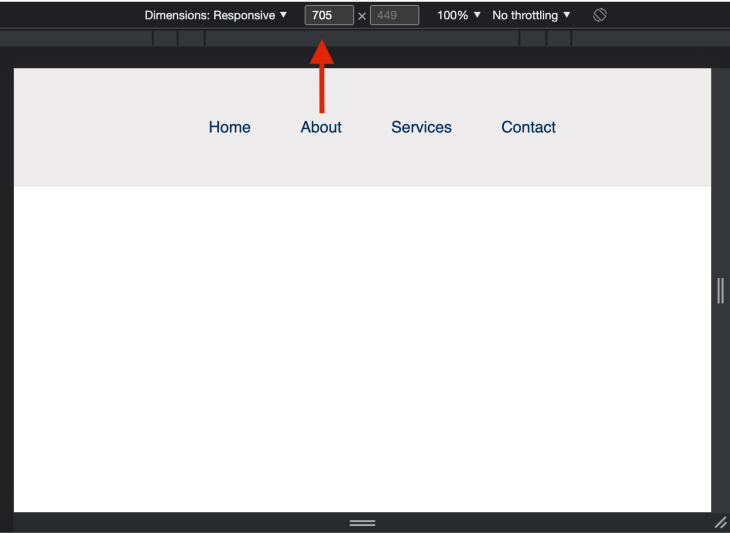

Screen size more than 700px:

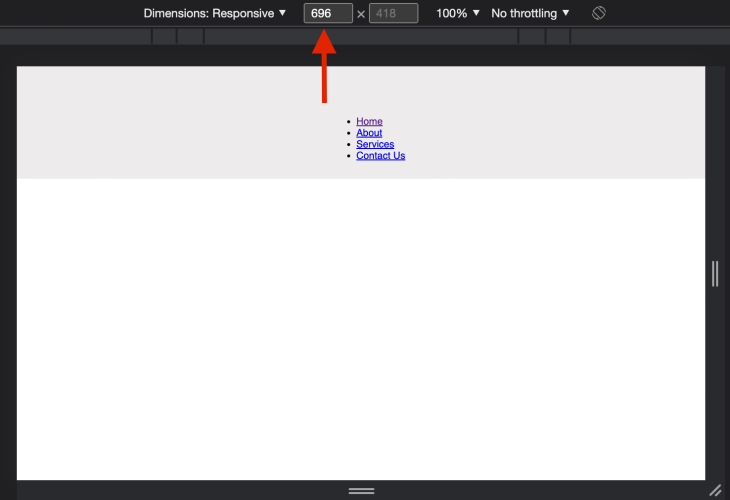

Screen size less than 700px for comparison:

From now on, we have to add all code blocks inside the .navigation style block because everything is nested.

The next piece of the code block is quite simple. This code will style our navigation button to be transparent and circular. We are making it transparent because the navigation icon element inside it will serve as the hamburger icon for this button.

&__button {

background-color: transparent;

height: 7rem;

width: 7rem;

top: 6rem;

right: 6rem;

border-radius: 50%;

z-index: 2000;

box-shadow: 0 1rem 3rem rgba($color-black, 0.1);

text-align: center;

cursor: pointer;

}

Now, we will style our hamburger icon. We will use the before and after pseudo-classes with position: absolute. Finally, we’ll add a little hover effect on our icon using the hover pseudo-class.

&__icon {

position: relative;

margin-left: 2rem;

&,

&::before,

&::after {

width: 4rem;

height: 3px;

background-color: $color-black;

display: inline-block;

}

&::before,

&::after {

content: '';

position: absolute;

left: 0;

transition: all 0.2s;

}

&::before {

top: -0.65rem;

}

&::after {

top: 0.65rem;

}

}

&__button:hover &__icon::before {

top: -1rem;

}

&__button:hover &__icon::after {

top: 1rem;

}

At this point, our hamburger menu icon should appear on the screen like in the image below:

![]()

Now, on the button press (or check), we want our hamburger icon to transform into an “X” close icon to indicate that our navigation bar is visible now and that further presses on it will close our navigation bar.

To do this, copy the below code, and we’ll be good to go with our icon.

&__checkbox:checked + &__button &__icon {

background-color: transparent;

}

&__checkbox:checked + &__button &__icon::before {

top: 0;

transform: rotate(135deg);

background-color: $color-white;

}

&__checkbox:checked + &__button &__icon::after {

top: 0;

transform: rotate(-135deg);

background-color: $color-white;

}

checked pseudo-class that is present in our checkbox element+ CSS selector. The + CSS selector helps us to select the element that is placed immediately after the specified elementbefore and after pseudo-elements of our icon to make it look like an “X”We’ll move forward by adding our background overlay. The logic behind our background is quite simple; we’ll add the background color on our button and, initially, it won’t be visible because its z-index would be behind the checkbox button.

As soon we click the checkbox, we will scale our background to cover the whole screen, and our navigation items become visible.

Copy the code below to achieve this.

&__background {

background: radial-gradient(

rgba($color-blue, 1),

rgba($color-purple, 1)

);

height: 6rem;

width: 6rem;

position: fixed;

top: -1rem;

right: 0rem;

z-index: -1000;

display: none;

border-radius: 50rem;

}

&__checkbox:checked ~ &__background {

@include respond(s-hundred) {

display: block;

transform: scale(80);

}

}

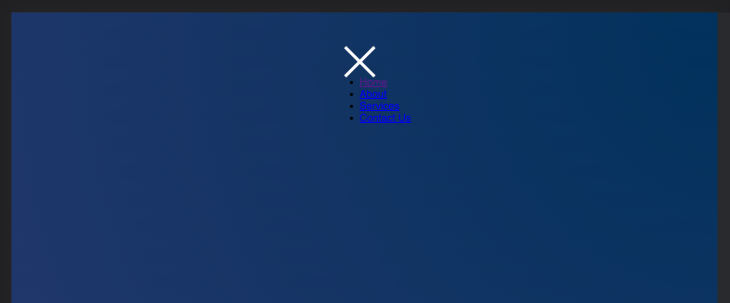

After applying the background overlay, the navbar should look like this:

The last thing remaining is to style our navigation items. For context, the navigation items should only appear when we click on the hamburger icon. It will cover the whole screen to offer a positive user experience on smaller screens.

Lastly, it should disappear once we click on the icon again. Some basic styling logic has gone into this code block, which is very similar to what we have done in the rest of the tutorial.

&__nav {

position: fixed;

margin-top: 1rem;

padding: 1.2rem;

font-size: 1.5rem;

font-weight: 400;

z-index: 1500;

@include respond(phone){

padding: 0;

}

}

&__list {

list-style: none;

opacity: 0;

visibility: hidden;

margin-top: 50%;

}

&__item {

&:not(:last-child) {

margin-bottom: 1.5rem;

}

}

&__link {

text-decoration: none;

color: $color-white;

&:hover {

color: $color-blue;

}

}

&__checkbox:checked ~ &__nav &__list {

opacity: 1;

visibility: visible;

transition: all 0.5s;

}

&__checkbox:checked ~ &__nav {

@include respond(s-hundred) {

font-size: 4rem;

position: absolute;

top: 32rem;

left: 50%;

transform: translate(-50%, -50%);

}

}

&__checkbox:checked ~ &__nav &__link {

@include respond(s-hundred) {

color: $color-white;

}

}

Finally, our custom sticky navigation bar should look like this on smaller screens:

You can style the navigation bar or its items as you want. I have the “X” close symbol in the middle, but it usually goes to the top-right side. You are free to do the rest of the styling as you see fit.

Finally, if you want to add some little animation on your navigation bar on scroll, you can add this little block of CSS code inside your header style block:

&__sticky {

padding: 5rem 10rem;

background-color: $color-gray;

box-shadow: 0px 3px 5px rgba($color-blue, 0.5);

}

Also, don’t forget to add this JavaScript code:

const navBar = document.getElementById('navbar');

window.addEventListener('scroll', () => {

navBar.classList.toggle('header__sticky', window.scrollY > 0);

});

The tools and techniques that CSS provides us right now are enough to build super-cool things like our navigation bar without using JavaScript. The full code from this demo is available in Codepen.

If we check the initial CSS styles that we have written, you must have noticed that for the navbar styles and for their counterparts, I have used position: fixed, which is very similar to another CSS property named position: sticky. Now, to understand why we have used fixed instead of sticky, we should know the difference between these two.

A fixed position fixates the element to the initial viewport. When we apply position: fixed to any element, no extra space is created for that element in the DOM and hence it looks like it’s floating over the viewport at a fixed position, like our navbar being fixed at the very top.

With position: sticky, the element is positioned according to the normal flow of the document and acts relative to its nearest scrolling ancestor or containing block until it comes into the viewport. Once it comes into the viewport, it turns to a fixed element (relative to the position of its ancestor) instead of going out through a scroll.

Read more about position here.

In the context of our navbar, we want it at the very top, and this is one of the reasons we have used position: fixed instead of sticky because the navbar will always be in the viewport, and there is no ancestor to it.

If you really want to use position: sticky instead of fixed for our navbar, you’d have to change a bunch of styles in our CSS.

To try it, let’s go back to the initial styles we wrote. Inside the .header block under the &__nav styles, which looks like this:

&__nav {

display: flex;

position: fixed;

top: 0;

left: 50%;

transform: translateX(-50%);

padding: 1.5rem 5rem;

justify-content: space-around;

align-items: center;

z-index: 100;

width: 100%;

transition: 0.3s;

}

Remove/comment out these styles and change the value of the position from fixed to sticky. Now, your style block should look like this:

&__nav {

display: flex;

position: sticky;

top: 0;

// left: 50%; (deleted style)

// transform: translateX(-50%); (deleted style)

// padding: 1.5rem 5rem; (deleted style)

justify-content: space-around;

align-items: center;

z-index: 100;

width: 100%;

transition: 0.3s;

}

We removed the left and the transform property because an element with position: sticky needs only position to stick, and in our case, it’s the top. Note that, some of the other styles we are removing are totally for the looks of our navbar.

If you try out our navbar now, it will be a mess because there are still a few modifications that we need to do. We removed the padding from our navbar because we need to make it look stable with our new styles. But, if you check out the &__sticky style block (the style that we append to our navbar dynamically on scroll), it still has some padding in it. So, the next step is to remove that one:

&__sticky {

// padding: 1.5rem 5rem; (deleted style)

background-color: $color-gray;

box-shadow: 0px 3px 5px rgba($color-blue, 0.5);

}

As per the above explanation, psotion: sticky works relative to its ancestor scrolling element or container. In our case, it’s the <header> element. Although, if we think about it, we want to see our navbar the whole time and not just while our header is in the viewport. So, we can remove our navbar from the inside of the header and paste it outside at the same level as this:

<header class="header">

</header>

<nav class="header__nav" id="navbar">

<ul class="header__list">

<li class="header__item">

<a href="#section-a" class="header__link">Home</a>

</li>

<li class="header__item">

<a href="#section-b" class="header__link">About</a>

</li>

<li class="header__item">

<a href="#section-c" class="header__link">Services</a>

</li>

<li class="header__item">

<a href="#section-d" class="header__link">Contact</a>

</li>

</ul>

<div class="navigation">

<input

type="checkbox"

class="navigation__checkbox"

id="navi-toggle"

/>

<label for="navi-toggle" class="navigation__button">

<span class="navigation__icon"></span>

</label>

<div class="navigation__background"></div>

<nav class="navigation__nav">

<ul class="navigation__list">

<li class="navigation__item">

<a href="#section-a" class="navigation__link">Home</a>

</li>

<li class="navigation__item">

<a href="#section-b" class="navigation__link">About</a>

</li>

<li class="navigation__item">

<a href="#section-c" class="navigation__link">Services</a>

</li>

<li class="navigation__item">

<a href="#section-d" class="navigation__link">Contact Us</a>

</li>

</ul>

</nav>

</div>

</nav>

Also, remove the position: relative style from your header block because our navbar is now relative to the whole viewport and not just the header:

.header {

height: 10vh;

background-color: $color-gray;

padding: 1.5rem;

// position: relative; (deleted style)

If we test out our navbar now, it will still not be working, but we are very close because it seems to stick at the top but it does not when we scroll past it.

This is happening because we have the overflow property set to hidden in our body styles. Any child element will not stick to its position in this scenario because there is no fixed height of the parent, and that makes it constrained because the child won’t know when the parent element is going out of the viewport.

You can read more about overflow here.

But, in our case, we can simply remove that property and we are good to go:

html,

body {

width: 100%;

margin: 0px;

padding: 0px;

// overflow-x: hidden; (deleted style)

}

After this, you will see that our navbar is working fine.

If we are using the position: sticky, we need to keep a bunch of stuff in mind to make it work properly. This is not the case with the position: fixed. Generally, for navbars, position: fixed is used because it sits at the top of the webpage. But, if you want to fix something in the middle of the webpage concerning some other element, position: sticky is the go-to solution.

You can find the CodePen link for this custom sticky navbar here.

You can do tons of stuff with only CSS. If you see tutorials on custom navigation bars or any other fancy stuff, for which you have to download some library or write some JavaScript code, then consider other alternatives first, because JavaScript is not the only way!

As web frontends get increasingly complex, resource-greedy features demand more and more from the browser. If you’re interested in monitoring and tracking client-side CPU usage, memory usage, and more for all of your users in production, try LogRocket.

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork around why bugs happen by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings — compatible with all frameworks.

LogRocket's Galileo AI watches sessions for you, instantly identifying and explaining user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

Modernize how you debug web and mobile apps — start monitoring for free.

Solve coordination problems in Islands architecture using event-driven patterns instead of localStorage polling.

Signal Forms in Angular 21 replace FormGroup pain and ControlValueAccessor complexity with a cleaner, reactive model built on signals.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the February 25th issue.

Explore how the Universal Commerce Protocol (UCP) allows AI agents to connect with merchants, handle checkout sessions, and securely process payments in real-world e-commerce flows.

Would you be interested in joining LogRocket's developer community?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

2 Replies to "Build a custom sticky navbar with CSS"

Clear and simple explanation. Thanks!

I have been looking for months for a navbar that has the Titles in the middle and I couldn’t find one until late one night I found your site. Thanks 🙂