Editor’s note: This post was last updated on 13 August 2021 to reflect any changes in technologies mentioned or updates to code. However, it may still contain information that is out of date.

At this point, React is one of the most loved libraries on the planet. There is a tremendous amount of interest in React, and new developers are brought to the platform because of its UI-first approach.

And while both the library and the entire React ecosystem have matured over the years, there are certain instances when we wonder, “What’s the right way to do this, exactly?”

It’s a fair question to ask — there isn’t always a firm “right” way of doing things. In fact, sometimes best practices aren’t so great. Some of them can compromise performance, readability, and make things unproductive in the long run.

In this article, we’ll review five generally accepted development practices that you can actually avoid when using React, why they’re avoidable, and alternative approaches that accomplish the same thing.

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

React is known for its speed and new optimizations are often added to each new update. But, before using these new optimizations, it’s often best to wait to see the actual performance.

Since it’s easier to scale React compared to other frontend platforms, developers don’t need to rewrite entire modules to make things faster. The usual culprit that causes performance issues is the reconciliation process that React uses to update the virtual DOM.

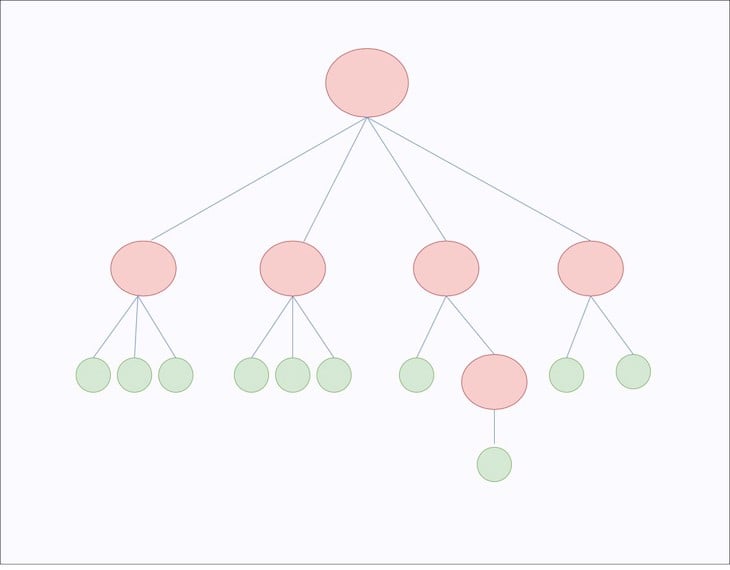

Let’s look at how React handles this under the hood. On each component render, React generates a tree that’s composed of UI elements, and the leaf nodes are the DOM elements.

When updating the state or props, React must generate a new tree with minimal changes and keep things predictable.

For instance, the tree can look like this:

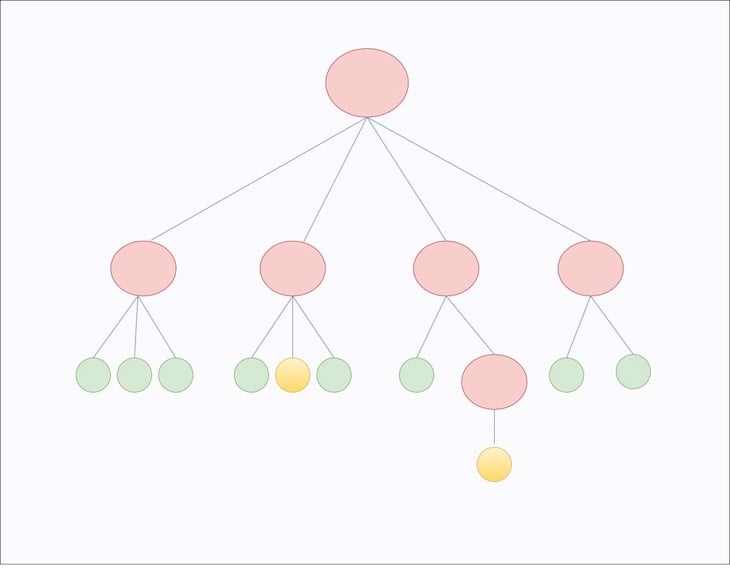

Imagine that the application receives new data and the following nodes, in yellow, need to update:

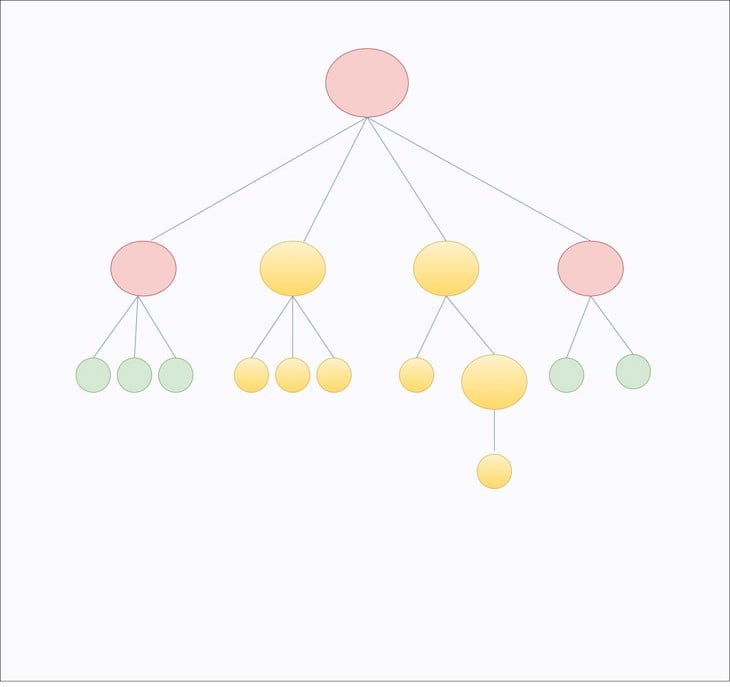

React usually rerenders the entire subtree instead of rendering only the relevant nodes:

When the state changes at top-order components, all components below it rerender. This default behavior is acceptable for a small-sized application. However, as the application grows, measuring the actual performance using the Profiler tool in the React DevTools can be beneficial.

The Profiler tool gives precise details about the time wasted on unwanted renders. If the numbers are significant, you can optimize them by preventing rerendering of the unaffected pure functional components. In this case, you can memoize the component using React.memo().

The React.memo() does a shallow comparison of the prop received and will only rerender a component if the prop differs and not just because the parent state changes.

const AChildComponent = React.memo(function AChildComponent(props) {

// component will re-render if the prop changes

return (

<div />

);

});

For class-based components, you can perform a shallow comparison of the props by extending a React.PureComponent or defining a custom implementation using shouldComponentUpdate():

shouldComponentUpdate(nextProps, nextState) {

if (this.props.color !== nextProps.color) {

return true;

}

if (this.state.count !== nextState.count) {

return true;

}

return false;

}

With this, the component won’t update if any other props or state change except color or count.

Apart from this, there are certain non-React optimization tricks that developers usually miss, but they impact the application’s performance. This can be avoided by considering unoptimized images and uncompressed build files.

If you’re building on dynamic images, images with huge file sizes can give the users the impression that an application is slow. To rectify this issue, compress the images before pushing them into the server or use a dynamic image manipulation solution instead.

Cloudinary is a great tool to optimize React images because it has its own React library; other options include Amazon S3 or Firebase.

Gzipping build files (bundle.js) can reduce file size drastically. However, you must modify the web server configuration.

Webpack has a gzip compression plugin known as compression-webpack-plugin. Use this technique to generate bundle.js.gz during build time.

Although single-page applications (SPAs) are awesome, they cause two main issues.

One, when an application initially loads, there is no JavaScript cache in the browser. If the application is big, the time taken to initially load the application will also be long.

And two, since the application renders on the client side, the web crawlers search engines use can’t index the JavaScript-generated content. The search engines will see an application as blank and then rank it poorly, driving away traffic.

That’s where the server-side rendering (SSR) technique comes in handy. In SSR, the JavaScript content initially renders from the server. After the initial render, the client-side script takes over and works like a normal SPA.

The complexity and cost involved in setting up a traditional SSR are higher because you need a Node.js/Express.js server. However, there’s good news if you’re in it for the SEO benefit. Google indexes and crawls JavaScript content without any trouble.

Here’s an excerpt from the Google Search Central Blog back in October 2015:

Today, as long as you’re not blocking Googlebot from crawling your JavaScript or CSS files, we are generally able to render and understand your web pages like modern browsers. To reflect this improvement, we recently updated our technical Webmaster Guidelines to recommend against disallowing Googlebot from crawling your site’s CSS or JS files.

If you’re only using SSR because you’re worried about your Google Page Rank, then you don’t need to use SSR. However, if you’re using SSR to improve the initial render speed, try an easier implementation of SSR using a library like Next.js.

This saves you time that you would otherwise spend setting up a Node.js/Express.js server.

The traditional CSS-in-CSS approach to introducing styles in React has been around for decades and works with React components. With this method, all stylesheets go into a stylesheets directory and import the required CSS into the component.

However, when working with components now, stylesheets don’t make sense anymore. While React encourages developers to think of applications in terms of components, stylesheets force you to think of it at the document level.

Various other approaches merge the CSS and JavaScript code into a single file. The inline style is probably the most popular among them:

import React from 'react';

const divStyle = {

margin: '40px',

border: '5px solid pink'

};

const pStyle = {

fontSize: '15px',

textAlign: 'center'

};

const TextBox = () => (

<div style={divStyle}>

<p style={pStyle}>Yeah!</p>

</div>

);

export default TextBox;

You don’t have to import CSS anymore, but you’re sacrificing readability and maintainability.

Apart from that, inline styles don’t support media queries, pseudo classes, pseudo elements, and style fallbacks. Sure, there are hacks that let you do some of them, but it’s not that convenient.

That’s where CSS-in-JSS comes in handy, and inline styles are not exactly CSS-in-JSS. The code below demonstrates the concept using styled-components:

import styled from 'styled-components'; const Text = styled.div` color: white, background: black ` <Text>This is CSS-in-JS</Text>

What the browser sees is something like this:

<style>

.hash234dd2 {

background-color: black;

color: white;

}

</style>

<p class="hash234dd3">This is CSS-in-JS</p>

A new <style> tag is added to the top of the DOM, and, unlike inline styles, actual CSS styles generate here. So, anything that works in CSS works in styled-components, too.

Furthermore, this technique enhances CSS, improves readability, and fits into the component architecture. With the styled-components library, you also get SASS support that’s been bundled into the library.

Ternary operators are popular in React; it’s my go-to operator for creating conditional statements and it works great inside the render() method.

For instance, they help you render elements inline. In the example below, I use it to display login status:

render() {

const isLoggedIn = this.state.isLoggedIn;

return (

The user is {isLoggedIn ? 'currently' : 'not'} logged in.

);

}

However, when you nest the ternary operators over and over, they can become ugly and hard to read:

int median(int a, int b, int c) {

return (a<b) ? (b<c) ? b : (a<c) ? c : a : (a<c) ? a : (b<c) ? c : b;

}

As you can see, the shorthand notations are more compact, but they make the code appear messy. Now, imagine if you had a dozen or more nested ternaries in your structure (it happens a lot often than you think).

Once you start with the conditional operators, it’s easy to keep nesting it until you reach a point where you decide that you need a better technique to handle conditional rendering.

But, the good thing is that you have many alternatives that you can choose from. You can use a Babel plugin like JSX Control Statements that extends JSX to include components for conditional statements and loops:

// before transformation

<If condition={ test }>

<span>Truth</span>

</If>

// after transformation

{ test ? <span>Truth</span> : null }

There’s another popular technique called Immediately-invoked function expressions (IIFE) . It’s an anonymous function that invokes immediately after defined:

(function() {

// Do something

}

)()

We’ve wrapped the function inside a pair of parentheses to make the anonymous function a function expression. This pattern is popular in JavaScript, but in React, you can place all the if/else statements inside the function and return whatever you want to render.

Here is an example that demonstrates how we’re going to use IFFE in React:

{

(() => {

if (this.props.status === 'PENDING') {

return (<div className="loading" />);

}

else {

return (<div className="container" />);

})()

}

There are more methods to run conditional statements in React and we’ve covered that in 8 methods for conditional rendering in React.

Closures are inner functions that have access to the outer function’s variables and parameters. Closures are everywhere in JavaScript, and you’ve probably used them whether you realized it or not:

class SayHi extends Component {

render () {

return () {

<Button onClick={(e) => console.log('Say Hi', e)}>

Click Me

</Button>

}

}

}

But when you are using closures inside the render() method, it’s actually bad. Every time the SayHi component renders, a new anonymous function is created and passed to the Button component.

Although the props haven’t changed, <Button /> will be forced to rerender. As previously mentioned, wasted renders can have a direct impact on performance.

Instead, replace the closures with a class method, which is more readable and easier to debug:

class SayHi extends Component {

showHiMessage = (e) => {

console.log('Say Hi', e)

};

render () {

return () {

<Button onClick={this.showHiMessage}>

Click Me

</Button>

}

}

}

For a function component, a function passed to a child component as prop also causes a rerender whether the child component is memoized or not. In this case, we use the useCallback Hook to memoize the function between renders:

const showHiMessage = React.useCallback((e) => console.log('Say Hi', e), []);

When a platform grows, new patterns emerge each day. Some patterns help you improve your overall workflow whereas others have significant side effects.

When the side effects impact your application’s performance or compromise readability, it’s probably a better idea to look for alternatives. In this post, I’ve covered some of the practices in React that you can avoid because of their shortcomings.

What are your thoughts about React and the best practices in React? Share them in the comments.

Solve coordination problems in Islands architecture using event-driven patterns instead of localStorage polling.

Signal Forms in Angular 21 replace FormGroup pain and ControlValueAccessor complexity with a cleaner, reactive model built on signals.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the February 25th issue.

Explore how the Universal Commerce Protocol (UCP) allows AI agents to connect with merchants, handle checkout sessions, and securely process payments in real-world e-commerce flows.

Would you be interested in joining LogRocket's developer community?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

4 Replies to "5 things not to do when building React applications"

Shouldn’t `showHiMessage = this.showMessage(‘Hi’)` in the last example be

`showHiMessage (e) { console.log(‘Say Hi’, e); }`

Hi- if a parent component re-renders, all of its children are also re-rendered, correct? Therefore, how does passing a closure as props to a child cause a performance decrease? Wouldn’t the Button component re-render every time SayHi component renders, regardless of if a closure is passed?

I obsessive compulsively write clean and tidy HTML and I’m being forced to use react, and it seems like react was deliberately designed to piss me and others like me off. Why is it so messy?

Haha. Well, being someone who loves React, I am slightly intrigued. Which part of React do you find annoying?