Editor’s note: This guide was last updated in December 2024 by Isaac Okoro to add a section on updated performance benchmarks and clarify the security advantages of Deno over Node.js.

Deno and Node.js are both performant JavaScript runtimes that differ in approach. Deno restricts file and network access unless explicitly permitted, making it secure by default, whereas Node.js provides unrestricted file and network access. Alongside this, Deno supports TypeScript natively, while Node.js requires extra configuration. Deno also includes a standard library with common utilities, while Node.js relies heavily on npm for additional packages. Finally, Deno focuses on security and simplicity, while Node.js offers extensive flexibility and compatibility.

Ryan Dahl, creator of Node.js, officially released Deno in May 2018. This new runtime for JavaScript was designed to fix a long list of inherent problems in Node.js.

Don’t get me wrong: Node is a great server-side JavaScript runtime in its own right (mostly due to its vast ecosystem and the usage of JavaScript). However, Dahl admitted at the 2018 JSConf EU that there are a few things he should have thought about more — security, modules, and dependencies, to name a few.

In his defense, it’s not like he could envision how much the platform would grow in such a short period of time. Also, back in 2009, JavaScript was still this weird little language that everyone made fun of, and many of its features weren’t there yet.

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

Deno is a secure TypeScript runtime built on V8, the Google runtime engine for JavaScript.

Deno was built with:

Deno’s features are designed to improve upon the capabilities of Node.js. Let’s take a closer look at some of the main features that make Deno a compelling alternative to Node.

Among the most important of Deno’s features is its focus on security.

Unlike Node.js, Deno 2 has ensured a steady focus on security through sandboxing. Sandboxing involves creating a safe isolated space to test code and application thus reducing the chances of unauthorized access to essential resources. Deno’s default sandbox disables network access, filesystem, environment variables, and subprocesses unless explicitly enabled by the developer through specified flags or permissions. This method helps reduce the threats posed by completely or partially trusted code by implementing code inside a container that restricts access to critical assets, unlike Node.js, where there is unrestricted system access by default.

To take a look at how the permission system works in Deno in contrast to Node.js, we’ll run a simple function that saves a string to a file using Deno and Node.js.

// write-file-deno.ts

const writeFile = async () => {

const encoder = new TextEncoder();

const data = encoder.encode('Hello world\n');

try {

// Deno 2's enhanced error handling

const status = await Deno.permissions.query({ name: "write", path: "." });

if (status.state !== "granted") {

throw new Deno.errors.PermissionDenied("Write permission required");

}

await Deno.writeFile('hello.txt', data);

console.log('File written successfully');

} catch (error) {

if (error instanceof Deno.errors.PermissionDenied) {

console.error('Permission denied. Run with --allow-write flag');

} else {

console.error('An error occurred:', error);

}

}

};

await writeFile();

The Deno script above encodes and write “Hello world” to a file. It also uses Deno’s permission checks to ensure the script has write access to the current directory before proceeding.

When trying to run the command below, it will prompt a request for permission:

deno run write-file-deno.ts

We are prompted with the following:

⚠️Deno requests write access to "/Users/user/folder/hello.txt". Grant? [a/y/n/d (a = allow always, y = allow once, n = deny once, d = deny always)]

We are actually prompted twice since each call from the sandbox must ask for permission. Of course, if we chose the allow always option, we would only get asked once.

If we choose the deny option, the PermissionDenied error will be thrown, and the process will be terminated since we don’t have any error-handling logic.

While running the command with an explicit permission flag the code execute seamlessly as seen below:

deno run --allow-write write-file-deno.ts # Will succeed

Deno also provides granular permission handling through enhanced path matching. And this includes providing the absolute path to the permission needed to execute the code:

deno run --allow-write=hello.txt write-file-deno.ts # Will succeed only for hello.txt

const fs = require('fs/promises');

async function writeFile() {

try {

await fs.writeFile('hello.txt', 'Hello world\n');

console.log('File written successfully');

} catch (err) {

console.error('Error writing file:', err);

}

}

writeFile();

In the script above, the function runs without requesting for any permission from the Node server.

This clearly shows how Deno is built around security unlike Node.js which gives full permission to the system.

Below is a table showing Deno’s security features versus Node.js:

| Feature | Deno | Node.js |

| Default permissions | Secure by default. No file, network, or environment access unless explicitly enabled by the developer | It has no restrictions by default. All scripts have full access to the filesystem, network, and environment |

| Permission flags | It uses granular flags to control access to the system:

–allow-read, –allow-write, –allow-net, etc. |

It has no equivalent built-in mechanism for controlling access at runtime. It permissions must be enforced manually |

| Environment variables | It restricts access to environmental variables unless –allow-env is used | It grants access to environmental variables by default |

| Execution environment | It runs in a secure sandbox by default, thus preventing unintended operations without consent | It runs scripts in an unrestricted environment unless additional tools like containers are used |

| Module system | It directly fetches and uses modules from URLs, thus reducing reliance on a centralized package registries | It requires a centralized registries like npm for modules, which can introduce supply chain vulnerabilities |

| Runtime flags | It can restrict permissions at runtime, e.g., –allow-read=${path} to allow reading only a specific path | No runtime permission system |

Deno, just like browsers, loads modules by URLs. Many people get confused at first when they see an import statement with a URL on the server side, but it actually makes sense — just bear with me:

import { assertEquals } from "https://deno.land/std/testing/asserts.ts";

What’s the big deal with importing packages by their URLs? The answer is simple: by using URLs, Deno packages can be distributed without a centralized registry such as npm, which recently has had a lot of problems. These are explained here.

By importing code via URL, it’s possible for package creators to host their code wherever they see fit — decentralization at its finest. No more package.json and node_modules.

When we start the application, Deno downloads all the imported modules and caches them. Once they are cached, Deno will not download them again until we specifically ask for it with the --reload flag.

There are a few important questions to be asked here:

Since it’s not a centralized registry, the website that hosts the module may be taken down for many reasons. Depending on its being up during development — or, even worse, during production — is risky.

As we mentioned before, Deno caches the downloaded modules. Since the cache is stored on our local disk, the creators of Deno recommend checking it in our version control system (i.e., git) and keeping it in the repository. This way, even when the website goes down, all the developers retain access to the downloaded version.

Deno stores the cache in the directory specified under the $DENO_DIR environmental variable. If we don’t set the variable ourselves, it’ll be set to the system’s default cache directory. We can set the $DENO_DIR somewhere in our local repository and check it into the version control system.

Constantly typing URLs would be very tedious. Thankfully, Deno presents us with two options to avoid doing that.

The first option is to re-export the imported module from a local file, like so:

export { test, assertEquals } from "https://deno.land/std/testing/mod.ts";

Let’s say the file above is called local-test-utils.ts. Now, if we want to again make use of either test or assertEquals functions, we can just reference it like this:

import { test, assertEquals } from './local-test-utils.ts';

So it doesn’t really matter if it’s loaded from a URL or not.

The second option is to create an imports map, which we specify in a JSON file:

{

"imports": {

"http/": "https://deno.land/std/http/"

}

}

And then import it as such:

import { serve } from "http/server.ts";

In order for it to work, we have to tell Deno about the imports map by including the --importmap flag:

deno run --importmap=import_map.json hello_server.ts

Versioning has to be supported by the package provider, but from the client side it comes down to just setting the version number in the URL like so:

https://unpkg.com/[email protected]/dist/liltest.js

Deno aims to be browser-compatible. Technically speaking, when using the ES modules, we don’t have to use any build tools like webpack to make our application ready to use in a browser.

However, tools like Babel will transpile the code to the ES5 version of JavaScript, and as a result, the code can be run even in older browsers that don’t support all the newest features of the language. But that also comes at the price of including a lot of unnecessary code in the final file and bloating the output file.

It is up to us to decide what our main goal is and choose accordingly.

Deno makes it easy to use TypeScript without the need for any config files. Still, it is possible to write programs in plain JavaScript and execute them with Deno without any trouble.

Deno has been steadily growing for quite some time now. Deno v1.0 was officially released on May 13 to much fanfare and has been growing steadily ever since.

The most recent stable release at the time of writing is Deno v1.7.0, published on Jan. 19, 2021. The latest version of Deno features improved compilation and data URL capabilities. Highlights of the new release include the ability to cross-compile from anything in stable, supported architecture (including Windows x64, MacOS x64, and Linux x64) with deno compile. In addition, deno compile now generates binaries that are 40–60 percent smaller than those generated by Deno v. 1.6, as well as binaries that have built-in CA certificates, custom V8 flags, locked-down permissions, and more.

Other notable features in Deno v.1.7 include support for data URLs, support for formatting Markdown files with deno fmt, and a --location flag to set document location for scripts. Learn more about the most recent updates to Deno.

With its decentralized approach, Deno takes the necessary step of freeing the JavaScript ecosystem from the centralized package registry that is npm.

Comparing the performance of Node.js and Deno is hard due to Deno’s relatively young age. Most of the available benchmarks are very simple, such as logging a message to the console, so we can’t just assume that the performance will stay the same as the application grows.

One thing we know for sure is that both Node.js and Deno use the same JavaScript engine, Google’s V8, so there won’t be any difference in performance when it comes to running the JavaScript itself.

The only difference that could potentially impact performance is the fact that Deno is built on Rust and Node.js on C++. Deno’s team publishes a set of benchmarks for each release that presents Deno’s performance, in many cases in comparison to Node. As at March 2021, it seemed Node.js performs better when it comes to HTTP throughput and Deno when it comes to lower latency.

However, this isn’t the case in 2024, as recent benchmarks show that Deno has lower average latencies than Node.js. Deno also edges Node.js in HTTP throughput benchmarks by handling the most data. Overall, Deno shows itself to be the more performant of the two frameworks

A common misconception about Deno’s first-class TypeScript support is that it somehow affects runtime performance due to type checking. I couldn’t find where that misconception originated, but, as anyone who knows the first thing about how TypeScript works will tell you, TypeScript only checks types during transpilation. Therefore, there’s no way it could negatively impact any kind of runtime performance. Once we use the bundle command, the output is a single JavaScript file.

All in all, both runtimes are extremely fast and make use of heavy optimizations to deliver the best possible performance. I don’t think either Deno or Node.js will be able to significantly outperform the other.

Deno’s goal is not to be a Node replacement, but an alternative. I would say that the majority of developers are happy with the way Node.js is evolving and aren’t really looking to switch things up.

Deno’s focus on security and the possibility of bundling the entire codebase into a single file presents a great opportunity for Deno to become the go-to tool for JavaScript developers when it comes to creating utility scripts that may have otherwise been written in languages such as Bash or Python.

If you’re trying to decide which one to choose, I would stick with Node as it’s mature, stable, and comes with a dedicated developer ecosystem. Below are some real-world use cases where you might choose to use one runtime over the other:

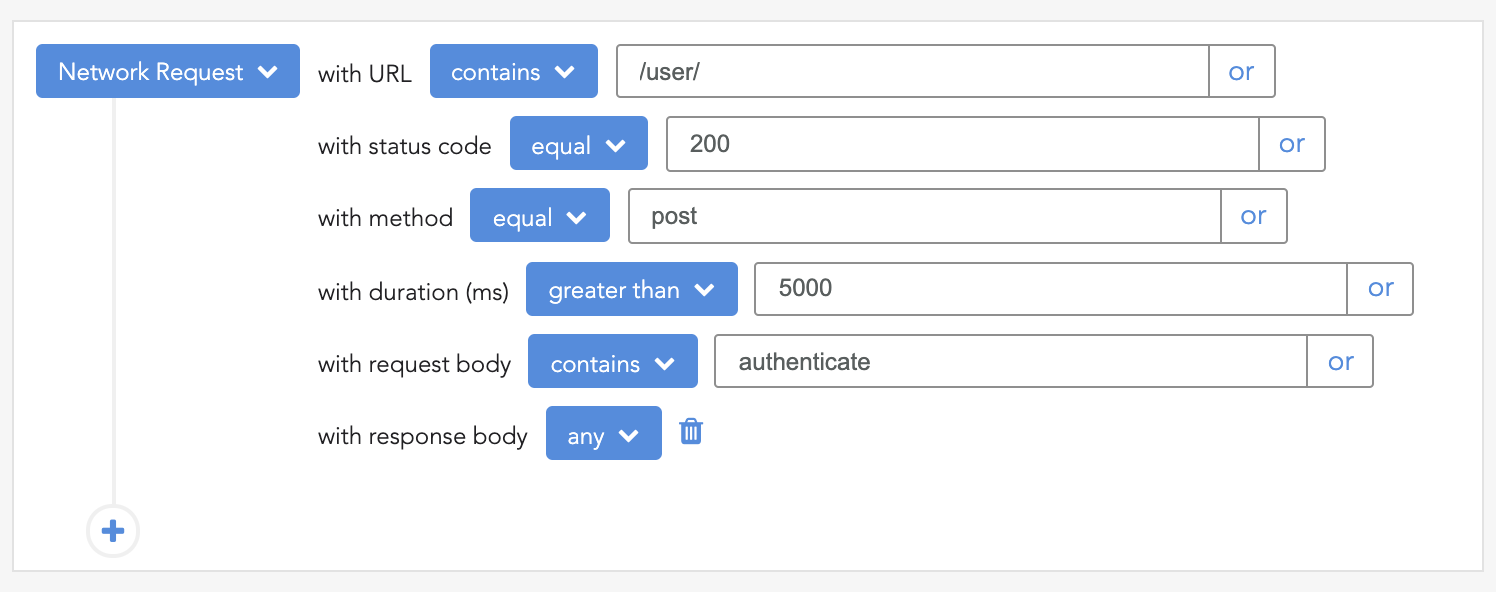

Monitor failed and slow network requests in production

Monitor failed and slow network requests in productionDeploying a Node-based web app or website is the easy part. Making sure your Node instance continues to serve resources to your app is where things get tougher. If you’re interested in ensuring requests to the backend or third-party services are successful, try LogRocket.

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork around why bugs happen by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings — compatible with all frameworks.

LogRocket's Galileo AI watches sessions for you, instantly identifying and explaining user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

LogRocket instruments your app to record baseline performance timings such as page load time, time to first byte, slow network requests, and also logs Redux, NgRx, and Vuex actions/state. Start monitoring for free.

Solve coordination problems in Islands architecture using event-driven patterns instead of localStorage polling.

Signal Forms in Angular 21 replace FormGroup pain and ControlValueAccessor complexity with a cleaner, reactive model built on signals.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the February 25th issue.

Explore how the Universal Commerce Protocol (UCP) allows AI agents to connect with merchants, handle checkout sessions, and securely process payments in real-world e-commerce flows.

Would you be interested in joining LogRocket's developer community?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

13 Replies to "What is Deno, and how is it different from Node.js?"

Why should people commit the modules into their repo? Man, it’s a waste of space. I had hoped Node.js creators will follow Go creators in terms of managing package.

Yes would it be possible to get a citation for the Deno team recommending storing the cache in the project directory?

@alastair

“Relying on external servers is convenient for development but brittle in production. Production software should always bundle its dependencies. In Deno this is done by checking the $DENO_DIR into your source control system, and specifying that path as the $DENO_DIR environmental variable at runtime.”

@Maciej thanks for the reply; I more meant a link to wherever the Deno team recommended storing the cache in the project directory *over* the system’s default cache directory.

Great article on the whole btw, really interesting stuff.

This is very surprising, it’s like asking to check-in node_modules to avoid dependency issues. Which actually would avoid a ton of issues but it makes the git repository huge and hard to use.

There are typically tens of thousands of files in node_modules, that’s why we avoid to commit this folder. I wonder how this will work in practice, I actually wouldn’t mind taking longer to clone a repo if it ensures that no-one will run into versioning issues in the project, due to different machines having installed different versions of some library.

i always push my modules, recommendation to ignore modules was wrong all the way

I don’t understand these complaints. How is bundling dependencies and cloning them later any different than doing an `npm install`? You have to download these files one way or another…

I guess the difference will be that in npm you are downloading a lot of garbage with every package like readme files etc. In deno on the other hand you will be caching nothing more than minified javascript.

Well, a package represents a artifact, while a repo should only hold source code and configs.

We don’t like package.json, that’s why we are using map JSON file …., We don’t like node_modules, that’s why we are using folder with a different name and store packages in our own repo …,

because module is code, it’s normal to push all the code to the repo and not rely on third party tools to do it for you each time on the client

I just wonder if allowing ‘anyone’ to publish from their own site, code that I’m going to use, is defeating the contention that Deno is improving security. I don’t know what npm does to ensure the code they host is not destructive or poorly written, but the downloading from npm site for me seems to provide a better way to do some type of inspection and validating of the code for the developer. If npm does nothing, then at least you can look at the popularity of the npm packages based on downloads. If anyone can publish from their own site, how can we even know the popularity of that code – who will track that?

Simple, Dont trust people who publish to their own sites, instead…

https://deno.land/x

It tracks populatity