A big part of UX research is obviously the people who participate in it. These people are extremely important because they’re far less biased than we are and the only people who can really tell us about themselves, the problems to be solved, and the effectiveness of the solutions that we’re building. But after all these years, finding quality research participants at an affordable price is still a tremendous challenge, but we keep hearing that research doesn’t have to be expensive, so how are UX designers actually going about it?

In this article, you’ll learn about the three methods of recruiting participants for UX research, their benefits and downsides, and how to go about them.

In short, no:

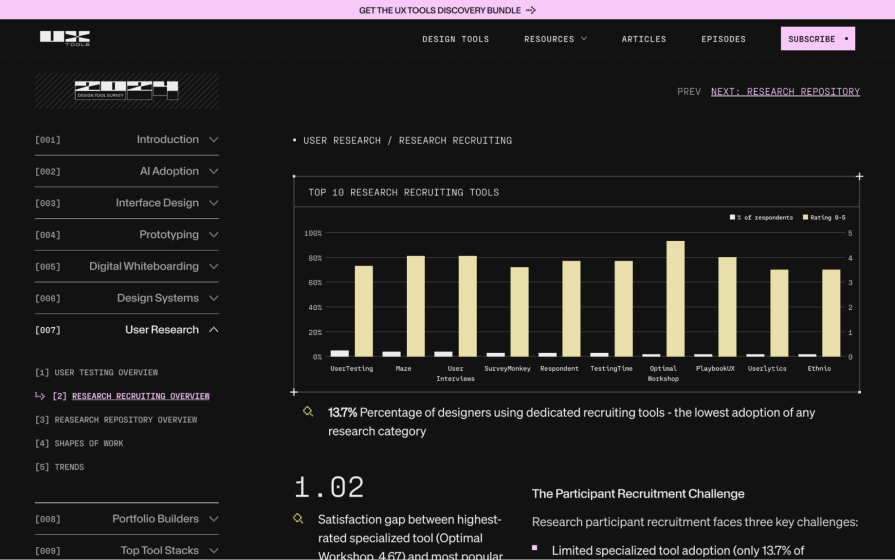

Not using dedicated research participant recruitment tools such as UserTesting anyway. According to the 2024 Design Tools Survey, only 13.7 percent of designers are using dedicated tools for recruiting research participants, a statistic that sharply declined from 28 percent the year before. 47.2 percent of designers (48 percent according to The Future of User Research Report 2025) say that finding qualified participants is the issue, but they also need to be paid for their time, right? It’s simply not cost-effective.

But what are the alternatives? Let’s find out.

This method requires a lot of time but provides great and sometimes unique benefits, not to mention the fact that if you don’t have users yet, this might be what it takes to find and research them. Simply put, this is a space for customers, users, visitors, or just people interested in your product’s space:

Starting the process of building a community for UX research should be a high-priority, day-one task, because it won’t fully pay off for a while.

The first benefit of building a community for UX research is that you’ll be able to reach a wider audience that includes potential users. The only other way to reach this segment is with on-site/in-app surveys and the like, but these people are more fleeting, so getting useful insights from them is harder.

On the flip side, you’ll be missing out on those that aren’t interested, which is fine if they’re not your target market, but if we’ve given them the wrong impression or the wrong information, we want to know about that, right? That’s why every method that I’ll outline today is vital — it’s not an either/or situation — always capture as much data as possible from as many contexts as possible, and document it in detail (more on that in a bit, though).

The second benefit is that these will be your most eager participants, and while there are some biases that come with that (that might disqualify them from certain studies), it nonetheless provides you with quick access to a panel of eager participants that are truly invested in your product, rather than only willing to give the bare minimum feedback needed to get their payout. As an added benefit, these recruits are typically happy to receive product perks rather than actual money — this still amounts to a gain for them but not really a loss for our business.

Similarly, they’re also likely to be your happiest/angriest users. Again, not a problem, it’s just important to understand that one channel isn’t representative of all users or potential users — document/label all data so that the full context is clear, especially for other stakeholders approaching the data for the first time. A research repository tool can help you with this.

Depending on your expertise and resources, your options are (with links to my ultimate favorite resources on how to create and/or scale them, although do note that the advice might include details relating to marketing and monetization, which you can ignore):

That being said, you don’t necessarily need to own the communities. However, keep in mind that the rules of unowned communities can prevent you from conducting business freely. In any case, pre-screen participants and post-filter the results accordingly, especially when cross-pollinating from various owned or unowned communities. Ultimately, you need to fully understand where participants are coming from/the context of the data. Again, and I can’t stress this enough, document/label data so that you can pull it from multiple sources at once according to how you’ve labeled/segmented it.

If sourcing from unowned communities, don’t shy away from smaller ones — some of the most engaged communities are those with less than 30 people. Today, these types of communities are very common, so ask around and see where people are spending their time.

Marketing isn’t the goal here, but it’s a shame to waste the opportunity. Make sure to capture consent for any marketing and avoid marketing to those who don’t give it. For participants, I suggest focusing more on the marketing of new features that they helped to shape, as this helps to keep them engaged. Otherwise, keep it very relevant/targeted.

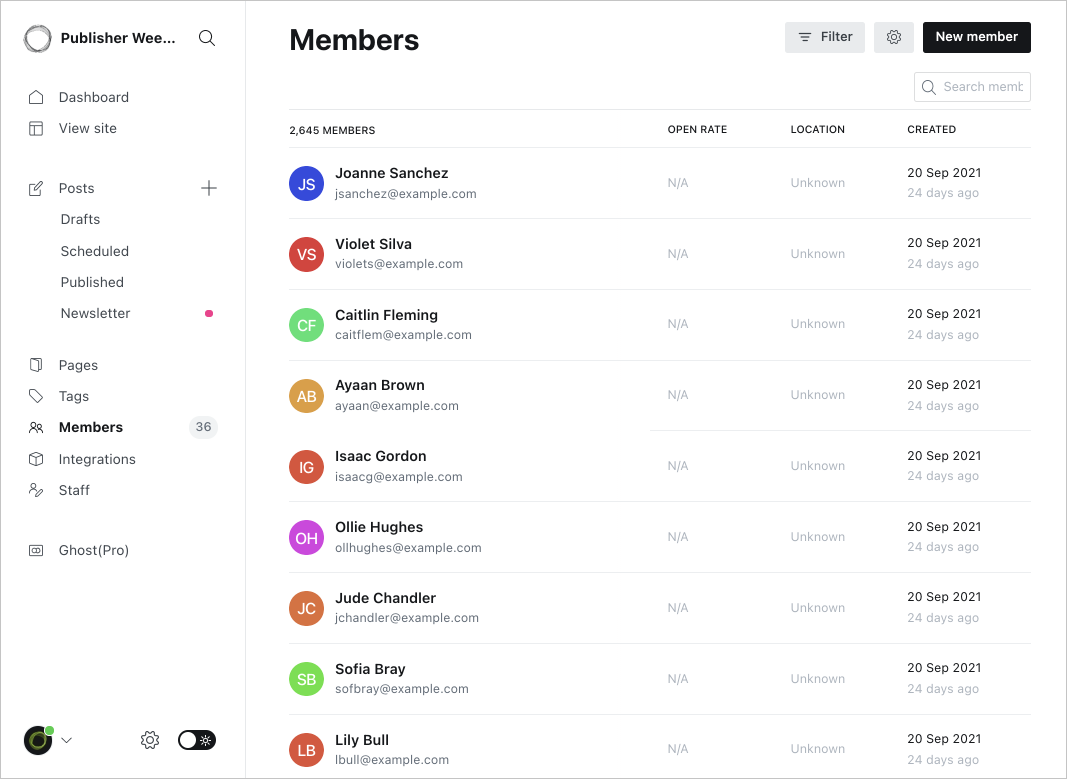

If your product has users already, you can leverage them to conduct UX research:

This is what most UX teams do, and I’m not here to convince you otherwise — it’s a terrific option with many benefits, but there are some downsides too, so let’s dive in.

Unlike other methods, the data resulting from this method is specifically representative of users actually using the product, an important segment that’s already segmented by nature (yay!).

Another benefit, assuming that you’re using a Customer Relationship Management (CRM) tool or CRM-like feature, maybe with built-in email features for extra convenience, is that this is the easiest audience to access. For example, if you were having difficulty with customer retention and wanted to get ahead of the problem, those that you’d need to research would be a part of this segment, whereas a community would be a more diverse set of folks that would require more segmentation and labeling.

Another comparison: while researching your product’s users can assist with customer retention, researching the non-user segment of your community can help you to cultivate or outright acquire new customers, including your very first ones. So again, it’s an additional method that you can utilize, not an alternative one.

As you might’ve guessed, this one’s super easy.

Simply reach out via email (or whatever) and invite them to participate in your study. The usual rules apply — create a file for them and note things that you’ve learned about them. These notes/labels supply additional context and enable you to segment participants further. With this particular method, you should be able to decipher how long they’ve been a customer/user, whether they’re possibly churning soon, what they’ve purchased, and so on from the get-go.

You are, after all, already acquainted with them, so you can begin to create something akin to a digital fingerprint from day one and then supplement that with further UX research. In fact, you should be doing this with all participants across all channels, at the very least, to ensure that you don’t end up with duplicate entries for people, tainting your data. Always collect email addresses for identification (be fully transparent about what this is for), tying any data sourced from your community to any data collected by reaching out directly, as well as any data autonomously collected by on-site/in-app methods such as surveys and analytics, which we’re going to move onto right this minute.

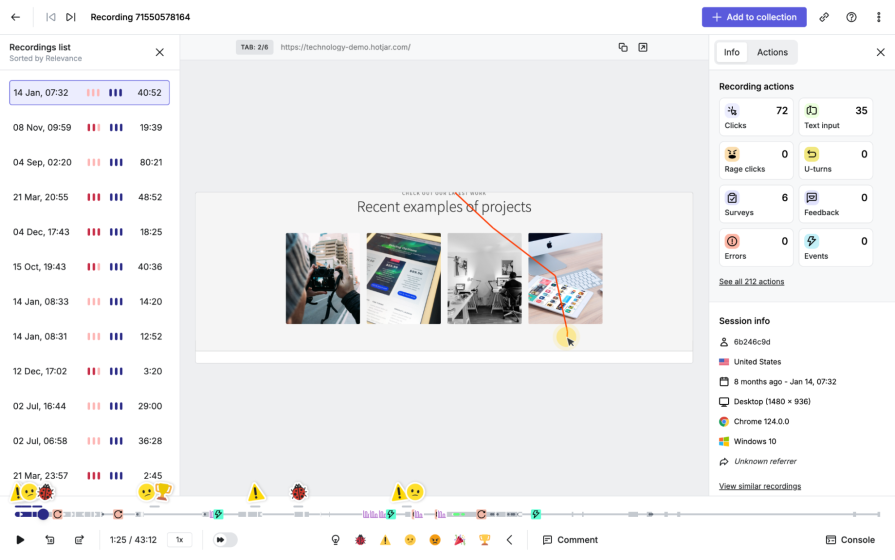

This method is more technical, but also more passive. It involves collecting data from those who use your website/app, whether they’re customers, users, or just visitors:

If you just synthesize the data into insights, then the research is totally unmoderated, but if you’re following up with participants, it’s moderated too. It depends on the method used, though — while it’s easy to follow up when surveying, since you can and should collect their email addresses to bind their data to data collected via other methods, it’s impossible to bind analytics, heatmaps, session recordings, and A/B test results to anonymous visitors.

Once again, let’s talk about the benefits and downsides.

As mentioned before, this approach targets customers, users, and visitors depending on the method and placement. Although uninterested visitors will likely ignore attempts to reach out, this is nonetheless the best method of accessing this audience.

The technicality of the implementation isn’t too tough, so I don’t consider that to be a true downside, and the mostly unmoderated nature of it all cancels out this downside anyway.

In addition to being unmoderated, this type of UX research is continuous as well — once you’ve set up your surveys/analytics/heatmaps/session recordings, they can accrue data for as long as you want them to (bar A/B tests, which you’d naturally dismantle once you’ve captured the data you need).

Also, and this probably goes without saying, this is the only method where data is collected during real scenarios, so you’re getting the truest and freshest data. However, keep in mind that non-surveying methods lack a lot of context, so the data has to be synthesized carefully and validated using summative research.

All in all, though, as long as you have a live product with people using it, this method is the least time-consuming, most versatile, and doesn’t even require participant recruitment.

Although dedicated tools exist, many tools conveniently cover surveys, heatmaps, session recordings, and A/B tests in a single implementation. The setup normally involves installing a script on your website/app, creating surveys and determining when they should show up, setting up heatmaps and session recordings, setting up A/B tests (when benchmarking multiple variations of a design), or simply setting up conversion flows using analytics.

Technically, marketing consent isn’t required for UX research, so logged-in users can have their data attributed to them. Other data will have to be anonymized, though.

Most businesses aren’t using research participant recruitment services, as they cost too much and the quality of the responses isn’t great. Although recruiting participants yourself can cost time in the short run, the long-term savings of time and money make it more than worth it.

The most difficult part is building a community of (or that includes) research participants, which is why I suggest working on that as soon as possible, especially if you don’t have actual users yet, as there aren’t really any effective ways to recruit research participants otherwise.

A bit further down the line, once you’ve acquired your first users, you’ll be able to approach them directly to recruit them for research studies.

In addition, having users (or just visitors, depending on the types of insights you’re looking for) enables you to passively capture analytics, survey responses, heatmaps, session recordings, A/B/multivariate test results via your website/app.

But it’s not just a matter of what you’re able to do. Each method has its pros and cons, foremost related to the type of audience it collects data from. Despite them having individual pros and cons, though, you can counteract their downsides by using all of the methods (at the appropriate times, of course).

Just remember, since you’re collecting data from all kinds of people in all kinds of contexts, you must file people, tag their data, and note the context to ensure that you acquire the right insights when needed. To acquire high-quality, accurate insights, you’ll also need to screen participants and filter out bad data from time to time.

It’s a lot of work, but it’s better than paying to recruit participants using recruitment tools, which, as mentioned before, yields data of questionable quality at a not-so-great price, not to mention that you’ll still need to put in most of the work mentioned above regardless. However, there are some secondary tools (the actual UX research tools being the primary ones) that are extremely underutilized in the design industry that can help with the researchOps side of things. Dovetail (or similar) helps with the address-booking of participants, labeling of data, and documenting of research, not to mention that it also uses AI to generate insights using the data. Also, automation tools like Zapier can pull data collected using different tools into a single source of truth. And finally, if you’re not sure which research methods to use, our handy introduction to the different types of research has you covered.

Got a question? Ask it in the comment section below!

And as always, thanks for reading.

LogRocket's Galileo AI watches sessions and understands user feedback for you, automating the most time-intensive parts of your job and giving you more time to focus on great design.

See how design choices, interactions, and issues affect your users — get a demo of LogRocket today.

There’s no universally “best” design language. This section breaks down when Linear-style design works well, how to build beyond it (or start from Radix UI), why it felt overused in SaaS marketing, and why conversion claims still need real testing.

Minimal doesn’t always mean usable. This comparison shows how Linear-style UI keeps contrast, affordances, and structure intact, unlike brutalism’s extremes or neumorphism’s low-clarity depth effects.

Linear-style UIs look simple, but the theming system has to do real work. Here’s how to meet WCAG 2.2 contrast requirements across light, dark, and high-contrast modes — whether you’re using a UI library or rolling your own tokens.

As product teams become more data-driven, UX designers are expected to connect design decisions to metrics. But real value comes from interpreting data, questioning assumptions, and bringing human behavior back into the conversation.