Design evaluation can be quite a puzzle. There’s a thin line between what you can “objectively” judge in design and its subjective nuances. But when you evaluate the effectiveness of a design, it’s essential to consider both holistically.

Objective criteria can be straightforward. They provide a structured framework for assessing usability, accessibility, and adherence to established standards. These criteria, rooted in principles such as anthropometry, heuristics, and standardized norms like ISO 9241, offer a tangible basis for evaluation.

But design excellence goes beyond meeting technical specifications. It encompasses subjective elements that tap into human psychology, emotions, and cultural associations. Subjective criteria encompass factors like personal preferences, emotional responses, and cultural influences, which significantly impact how we perceive a design.

Understanding and balancing both objective and subjective aspects are crucial for creating designs that both meet functional requirements and resonate with users on a deeper level.

Let’s talk about how we do this effectively.

An objective criterion for judging a design would be a set of rules that designers have to follow universally. Such things do exist, and we use them to ensure that a design is usable, comfortable, and acceptable to our users.

Objective criteria don’t give information about the aesthetic qualities of a design, and a lot of outdated designs were objectively good but wouldn’t be liked today.

Design aspects that can be judged objectively are:

I’m going to teach you how to use these to tell if your design is good.

Imagine getting in a car with a steering wheel so thick your hands can’t grab it, and the car requires pushing twenty-three random commands to start. That wouldn’t make sense even if the car is technically working.

It seems obvious that a design that would be out of reach for the user’s limbs or too hard to understand for the user’s mind would be bad. That’s why researchers defined a few metrics and regulations to serve as a basis for any product.

Anthropometry studies the physical capabilities of users. During the World Wars, militaries were developing new machines, notably tanks and submarines, but they weren’t designed with humans in mind. This resulted in some absurd situations, like French soldiers sitting in tanks on each other’s shoulders to drive and operate the cannon simultaneously.

To avoid bad design, engineers took every kind of measurement on soldiers and later on civilians to know the acceptable range of design. And that data is still used today.

Why are door handles at a certain height? Because it matches the resting position of the user’s arms and allows a large movement amplitude. Why is there so little place in planes? Because seats were designed with the minimum acceptable space in mind.

Anthropometric data are a good basis to objectively judge a design. They are the bare minimum to make something suited for the human body. But keep in mind, a design respecting the numbers isn’t necessarily good.

Remember, anthropometrical data are made to accommodate 95 percent of the users following a normal distribution. Very tall and very small people are excluded. To add to that, the data is theoretical because researchers supposed that people are always in an upright position. Writing that half-seated, slouching down in my chair, I can say with confidence that people rarely keep a straight position for long.

The first phablets failed their introduction on the mobile device market because it was way too large for normal people to hold in one hand. On the contrary, iPhones tend to get taller but rarely wider:

Other than these anthropometrical rules, accessibility is also a way to objectively evaluate a design. This topic can be harder to grasp because a lot of products we consider to have “good design” aren’t totally accessible.

Still, the WCGA edited a strict list of rules that are easy to follow. For example: text in an interface shouldn’t be smaller than 12px and should be around 16px to maximize readability. Evaluating the accessibility of a design objectively is relatively easy. Again, what is recognized by the WCGA is a bare minimum, and it will be up to the designer to define if it is enough for the users.

Accessibility rules cover a lot of aspects of a design and even touch the cognitive psychology that I can’t cover here. You should follow some clear rules in cognitive psychology, like the gestalt principle that influences how the users perceive elements linked together, or how much information you can stock in the working memory. However, it’s a bit harder to evaluate accessibility with psychology objectively and requires the designer to understand their user flow before making any judgment calls.

To define what makes a good design, UX researchers decided on a list of elements that should be included in any design one way or another to maximize usability and user experience. This is what we call heuristics. The most famous ones are Nielsen’s heuristics and Bastien and Scapin’s heuristics.

Referring to heuristics is really the basis of any audit in UX design. Even if they are not strict rules, the way to follow them can take a lot of forms. Designers must answer them one way or another if they want to create a good product.

Heuristics are not just a random list some designers came up with one day. If we look at Bastien and Scapin heuristics, they are the result of a Canadian study in the ‘90s, piling up every element of what was judged as “good design.” They came up with eight big topics divided into sub-topics covering every aspect of design. The heuristics were then tested and proved to help identify usability problems faster.

What can be objectively judged is if you can answer yes or no to every aspect on a heuristic list. But whether the solution is suited for the use case will depend on the context and should be judged subjectively by an expert.

ISO 9241 defines the criteria composing usability: a targeted population performing a specific task in a specific context. If one of these variables changes, a product can become unusable.

Those aspects are subjective for evaluation. Who are the real users? What is the true goal of a product? It depends. What can be considered objective, on the other hand, is how to evaluate usability.

By running user tests, we can document and compare metrics. Some could argue that user testing isn’t objective because it depends on your sample size and testing methods. But collecting large amounts of data to define a mean value is also the basis of every human science and one proven methodology to make human behavior objective.

The three elements to test are efficacity, efficiency, and global satisfaction:

Efficacity is the capacity to complete a goal. For example, a car and a bike have the same efficacity to travel a short distance.

Efficacity is measured by counting how many times a user doesn’t finish a task either by dropping out or because they made too many errors. To continue on the example, a car can have less efficacity than a bike if the users can’t find a place to park to complete their trip.

Efficiency is the amount of resources needed to reach a goal. Countable resources must be defined beforehand: time needed to complete a task, number of clicks, fuel burnt, money spent — it all depends on what needs to be counted. Generally, the less the better.

Satisfaction is how willing the users are to interact with the interface. It seems less objective than efficacity and efficiency, but by standardizing answers through a questionnaire like the SUS, you can objectively compare results.

As we saw, you can evaluate some elements of design from an objective point of view. It is mainly the overall usability that you can compare to norms, heuristics, and objective data, but it doesn’t say if the design choices are innovative, if the design is aesthetic, or if the design is answering a real problem. That’s why designers also need a dose of subjectivity.

When judging a design, we are naturally biased by our personal tastes. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, as long as we are self-aware and know the root of our tastes.

Personality, culture, and history condition what people like or dislike. An introvert and an extrovert will not like the same kind of design, or rather, they can like the same kind of design but not for the same reason. When browsing for a hotel room, an introvert might like the general atmosphere, the minimalistic design, the calm, whereas the extrovert could like the luxurious aspect and the view of the city.

Emotions will also impact our perception of a design. It’s not the same to judge something when you’re in a good mood versus after you’ve driven twelve hours.

Let’s cover how we understand subjectivity.

When we see any object, our natural reaction is, “Oh, it reminds me of…”. That aspect of human behavior will impact whether we perceive something positively or negatively.

A car with smooth curves will be associated with waves and elegance. Simply the word smooth connotes something positive. On the contrary, a car with harsh angles will be compared to a trash can or a yogurt cup.

The associations we make are totally arbitrary and don’t necessarily reflect the usefulness of a product, but they will impact how the customers receive it.

The memory aspect is also what influences our tastes in terms of color meanings. Green is the color of nature and organic food in the West but doesn’t hold that association everywhere. Purple is associated with creativity and luxury in the West, but with death in some countries in Asia. The choice of color in a product will be seen as coherent or not depending on what we interpret through this color.

Next, structures can be subjective, though some are rooted in psychology. We tend to prefer continuous lines and curves over breaking points and angles. Epurated designs tend to be smooth and more agreeable to the eyes. Charged design and hard angles tend to be less appreciated. There are a bunch of criteria like this that researchers found to impact our subjective judgment.

To go one step further, we can point out that researchers have defined a list of criteria that are impactful on what we like or not. In a study published in 2016, Mathieu Zen

Jean Vanderdonckt defined criteria that impact how people judge an interface. The criteria are

Those are some examples of criteria we use to unconsciously evaluate something. From the study, participants tend to judge more positively interfaces that are well-balanced, low-density, and centered. Simplicity and symmetry were moderately important.

Even if it’s nice to know we can measure things more or less objectively, and that subjectivity is influenced by our own experience and some universally perceived shapes, the most important thing in UX design is still context.

A design is only good in a given context; nothing is universal. Getting back to ISO norm 9241, a well-crafted design is the meeting point between a kind of user, a given context, and a specific task/goal. If you change one of these parameters, a design can go from good to bad in an instant.

And unfortunately, understanding those parameters is the hardest task in judging a design. There is no easy way to do it other than studying and research.

Interpreting context can be difficult. With mobile devices, people can use the same tool on their sofa or when walking through a crowd. It’s best to design for the worst situation possible, but in some cases, it’s even better to make two different designs corresponding to different points of interaction. An example of this is Airbnb being different on PC and mobile to accommodate calm vacation brainstorming and a stressful arrival.

You need to study your ideal user before and during the use of a product. It’s common to target an audience and later discover that another group has become the main user. The buyer might not even be the end user. For instance, a lot of healthcare devices are bought by children for their parents, resulting in a product that doesn’t help the end user but reassures the buyer.

And finally, you need to answer this for context: what is the true goal of a product? There is a notion called the “true task” that says there is always a difference between a supposed task and reality. To fully judge a design, understanding the true task is important. Keep testing, and never make assumptions!

Design evaluation needs a holistic approach that considers both objective and subjective criteria. Objective criteria, based on anthropometrics, accessibility guidelines, heuristics, and standardized norms, provide a framework for assessing usability

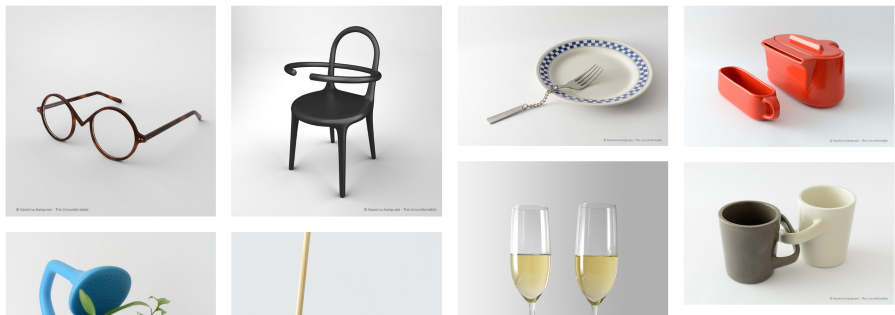

Subjective criteria, influenced by personal preferences, emotions, memories, cultural associations, and contextual factors, play a crucial role in shaping how users perceive and experience a design. Even if everyone has different tastes, the criteria shaping subjectivity are well documented and something you can analyze. Usability without emotion is boring, and a beautiful design without usability is useless:

Header image source: IconScout

LogRocket's Galileo AI watches sessions and understands user feedback for you, automating the most time-intensive parts of your job and giving you more time to focus on great design.

See how design choices, interactions, and issues affect your users — get a demo of LogRocket today.

Security requirements shouldn’t come at the cost of usability. This guide outlines 10 practical heuristics to design 2FA flows that protect users while minimizing friction, confusion, and recovery failures.

2FA failures shouldn’t mean permanent lockout. This guide breaks down recovery methods, failure handling, progressive disclosure, and UX strategies to balance security with accessibility.

Two-factor authentication should be secure, but it shouldn’t frustrate users. This guide explores standard 2FA user flow patterns for SMS, TOTP, and biometrics, along with edge cases, recovery strategies, and UX best practices.

2FA has evolved far beyond simple SMS codes. This guide explores authentication methods, UX flows, recovery strategies, and how to design secure, frictionless two-factor systems.