It hasn’t been too long since Adobe announced that their intent to acquire Figma for $20 billion had been terminated. Adobe has long dominated the creative market, offering software like Photoshop and Illustrator, which have become the industry standard in graphic design.

It seemed that the only things missing from their Creative Cloud suite of tools were a wireframing and prototyping tool, and design collaboration. Figma had both of these, through their main offering and their digital whiteboarding tool FigJam. When their merger failed to close, it gave industry competitors a glimmer of hope that there was still a chance to succeed in the market.

Recently, creative industry pioneer InVision announced the sale of their design collaboration tool Freehand to Miro, another competitor in the space, along with the discontinuation of the rest of their services by the end of 2024.

This news begs the question, where is the design collaboration software market headed? Will Miro soon become the Adobe of design collaboration? Let’s talk about the state of design collaboration services and what this might mean for the future of the industry.

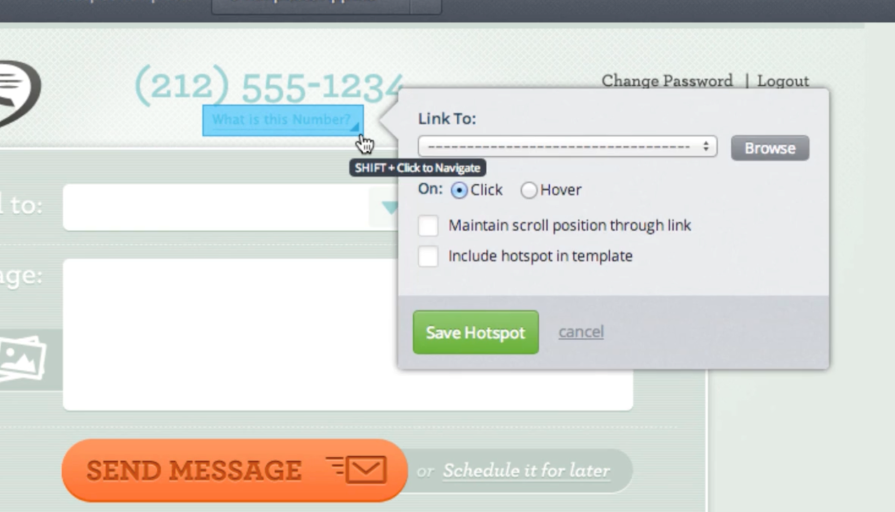

Launched in 2011, InVision was once a popular tool of choice in the design industry. Their prototyping, collaboration, and workflow features were used by many designers for the simplicity of creating interactive mockups for wireframes. By adding hotspots to your design screens, InVision enabled designers to quickly link them together and add transitions, making it feel like a live website or app without coding:

Over the years, InVision has introduced more advanced functionality but failed to truly innovate their product. They largely kept their core offering the same, which was a standalone prototyping tool. Users still had to navigate the challenges and frustrations of importing their designs from another tool, such as Sketch or Photoshop, into InVision.

Existing solutions were still inconvenient and time-consuming, especially when saving and transferring large files. This workflow caused friction for many designers, who eventually abandoned InVision to use other tools.

InVision’s use of hotspots was also not ideal because they often were a hassle to set up and not as accurate as the current tools on the market, which use the layers of the design as the interactive element.

However, because InVision only supported flat images of your designs, this was the best they could do. Over more than a decade, though, the company allowed their software to stagnate and failed to provide any sort of innovative solution that would address these common pain points for its users.

Half a decade after the initial release of InVision, the design industry was gifted the current reigning champion of collaborative interface design tools, Figma. Their web-based application offered a one-stop shop for designers to design, prototype, and collaborate with their teammates, all in one tool.

Their inclusive software solved the issues of navigating multiple tools as part of a designer’s workflow. Instead, designers could go from ideation to fully interactive prototype without leaving the app.

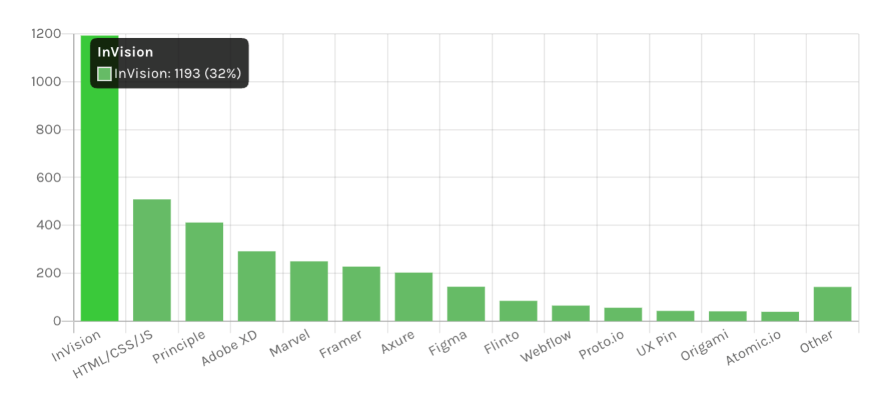

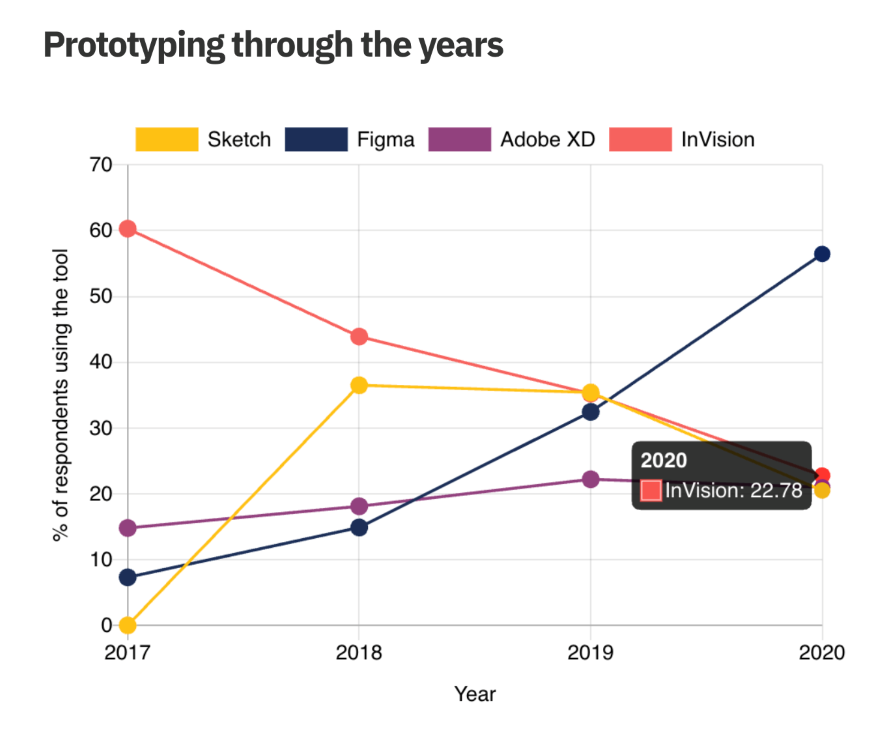

But InVision was still the prototyping tool of choice for designers in 2017. According to UX Tools’ 2017 Design Tools Survey, the company had almost a third of the market share, making them the clear winner at the time. On the other hand, Figma had less than 10 percent of users using its application for prototyping purposes:

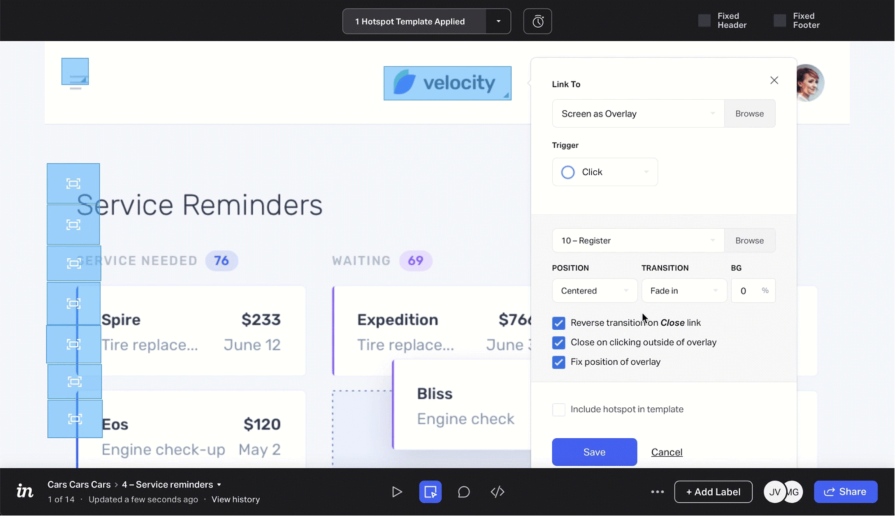

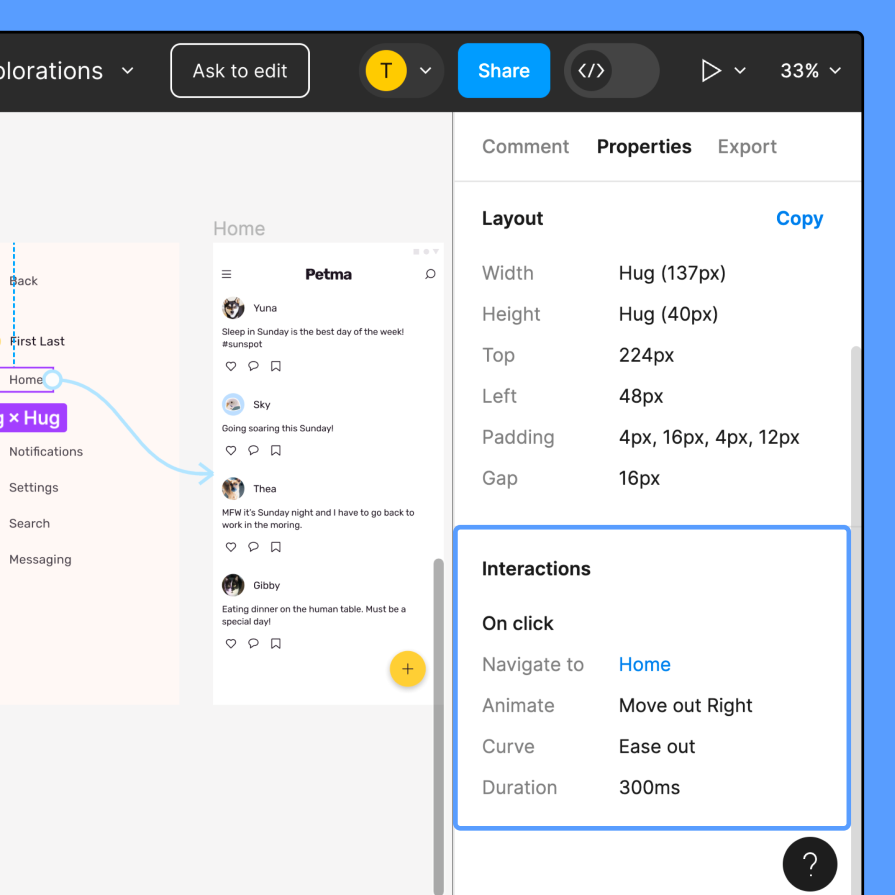

As an interface design tool, Figma was able to leverage the layers of a file as the interactive elements in a prototype, instead of using hotspots like InVision. This made it much more convenient to create prototypes quicker and more accurately.

Figma also didn’t require a space to manage a set of screens, like InVision had, because the file is already set up using frames that can be connected into a prototype flow:

With these powerful capabilities, designers slowly began to switch over to Figma from InVision over the next few years for their prototyping needs. Slowly but surely, Figma took the majority share of users in 2020, while InVision experienced a steep decline in active users:

In 2017, InVision announced the launch of their digital whiteboarding tool, Freehand. It competed against tools like Miro, Figma, and Sketch.

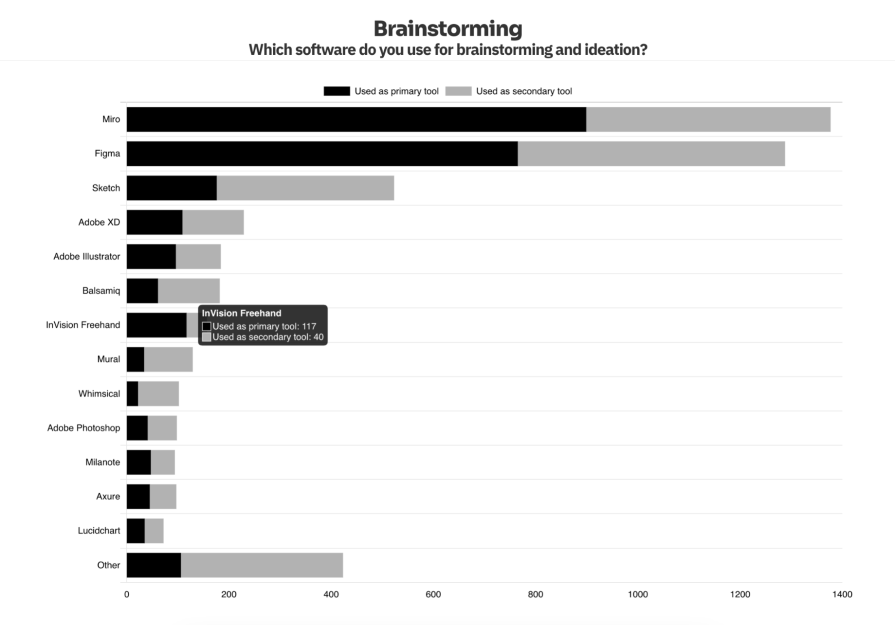

By 2020, the pandemic forced designers to work remotely, which led to a sudden rise in the use of digital whiteboarding and brainstorming tools. This presented an opportunity for InVision to regain some users with Freehand. However, according to UX Tools’ 2020 Design Tools Survey, Freehand was outchosen by its three bigger competitors as designers’ primary tools for brainstorming and ideation:

To top it all off, Figma released their own digital whiteboarding tool in 2021, FigJam. This further strengthened their presence in the market as an all-in-one interface design, prototyping, and collaboration platform.

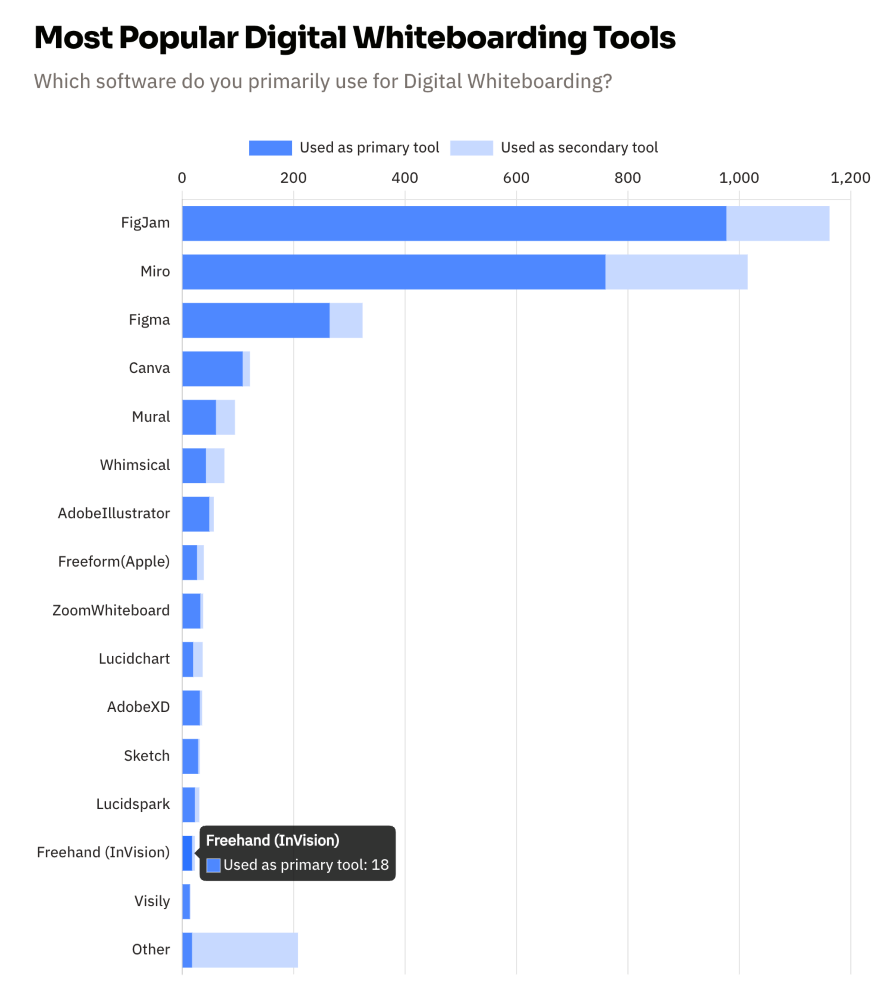

With Miro and Figma both dominating the design collaboration industry, InVision’s future wasn’t looking too good. As of 2023, InVision had less than 1 percent of designers using its tool for digital whiteboarding, according to UX Tools’ 2023 Design Tools Survey:

Now that leads us to 2024, when InVision announced the sale of Freehand to their biggest competitor, Miro, who dominates the digital whiteboarding space. Why was this deal allowed when just recently Adobe was forced to abandon the Figma acquisition?

Although Miro is the top brainstorming tool used by designers, their audience is much larger than just the design community. They are positioned as a visual collaboration and digital whiteboarding application.

Not only does Miro serve UX use cases, such as organizing user research notes or creating user flow diagrams, but they also cater toward any role that requires digital whiteboarding and remote collaboration. Since they are not tied to any design tool, their platform is often used by product managers, engineers, and marketers for workshops, agile ceremonies, and visualizing processes.

Adobe, by contrast, is a juggernaut of creative tools, including industry standards Photoshop and Illustrator. Acquiring Figma would have come with not only the preferred interface design and prototyping tool, but also FigJam, the preferred design collaboration tool. To top it off with owning their famous suite of creativity software for other types of creatives, such as graphic designers, animators, videographers, and photographers, Adobe would have monopolized and taken over most of the creative industry.

Miro’s acquisition of InVision’s Freehand simply consolidates and strengthens their digital whiteboarding offering, but doesn’t create a monopoly over the design collaboration market. A good deal of design collaboration is still done on Miro, especially since it is common for nondesigners to have access to Miro rather than a design-specific tool like Figma. However, their target market is not just designers, but any business that works with remote teams, so they don’t seem to pose any threat to the rest of the design industry.

As for Adobe, it doesn’t seem like they will continue pursuing the interface design space for now, as they have discontinued their investment in XD, their interface and wireframing tool.

However, it wouldn’t be a surprise if they attempted to acquire another design collaboration tool in the future, perhaps one not as big as Figma. By targeting a smaller competitor and adding it to their Creative Cloud, Adobe could potentially still have space to play in the design collaboration domain.

For the remaining design collaboration tools on the market today, such as Lucid, Mural, or Whimsical, the opportunity lies in your niche. Each of these tools is still able to find success in the market due to their focus on a specific sector of the market.

For example, Lucidchart appeals to teams that want to leverage their own data in technical diagrams. Whimsical aims to keep product teams aligned using both visuals and integrated documents. Mural positions themselves as an AI collaboration tool for enterprise teams.

In fact, with the rise of generative AI, we are still at the forefront of applying this technology to collaboration tools. We’ve started to see AI assistants and AI template generators within these tools, but there is still an incredible opportunity for these companies to continue developing their products with new applications of AI.

In the future, it won’t be unlikely that some of these tools merge with other collaboration or productivity tools, such as project management or file sharing tools, to form a centralized hub of collaboration and file management. They could also partner up with design tools to offer a more streamlined experience, just like what Figma offers with FigJam.

With the explosion in design collaboration services following the pandemic, there’s bound to be some level of consolidation down the road. After all, the fewer tools a designer needs to use, the better it is for their efficiency and productivity.

Companies are starting to follow the ecosystem model, where they offer all related services under one umbrella, such as Adobe Creative Cloud or Microsoft Office, either by organic growth or acquisition. This enables them to capture more users to use their services and keep them locked into the ecosystem.

Regulators love to shut down business deals from happening that could result in a potential monopoly over a market. The Figma acquisition by Adobe is one example of EU regulators preventing the creative giant from stealing even more market share into their ecosystem. Now, some might question if Figma will follow in Adobe’s footsteps, as they are seen as the top player in interface design and design collaboration today.

In terms of Figma monopolizing design collaboration, I don’t think there’s any need to worry about that. We’re already starting to some design teams flock to competitors on the interface design side like Penpot that offers an open-source platform.

Miro is another example of a competitor that isn’t directly selling to designers, but takes a chunk of market share. If Figma ever got to the size of Adobe, there’s a good chance regulators would step in if they felt threatened by a potential acquisition leading to a monopoly over the market.

Besides, design tools come and go. Just as InVision was once the favorite prototyping tool, the industry changes quickly and if companies aren’t able to evolve with it, they’ll eventually get left behind. There will always be the next tool that solves a painpoint in the market.

The key takeaway for designers is to not get caught up with the tools that you use. Your abilities as a designer come from your mind, your knowledge, and expertise, which is something that you will always have, no matter what tools you use.

LogRocket's Galileo AI watches sessions and understands user feedback for you, automating the most time-intensive parts of your job and giving you more time to focus on great design.

See how design choices, interactions, and issues affect your users — get a demo of LogRocket today.

Security requirements shouldn’t come at the cost of usability. This guide outlines 10 practical heuristics to design 2FA flows that protect users while minimizing friction, confusion, and recovery failures.

2FA failures shouldn’t mean permanent lockout. This guide breaks down recovery methods, failure handling, progressive disclosure, and UX strategies to balance security with accessibility.

Two-factor authentication should be secure, but it shouldn’t frustrate users. This guide explores standard 2FA user flow patterns for SMS, TOTP, and biometrics, along with edge cases, recovery strategies, and UX best practices.

2FA has evolved far beyond simple SMS codes. This guide explores authentication methods, UX flows, recovery strategies, and how to design secure, frictionless two-factor systems.