Regardless of skill level, very few developers write quality code on their first try. This is why experienced developers take time to refactor their code, even after they have an initial working solution. Refactors also happen over time as the app grows and evolves. Implementation details can and do change regularly.

When refactoring, it is essential to have good tests in place to prevent regressions and to keep yourself from making simple mistakes. But what if your tests aren’t quite as helpful as you think they are? If you’re not careful in how you write your tests, you may find yourself in this very trap.

In this article, we’ll take a look at a simple React component and observe how our test suite responds to simple refactors. We’ll use React Testing Library to highlight the power of testing how the user interacts with the app. We’ll also use Enzyme to explore the pitfalls of testing implementation details and the headaches this approach can bring.

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

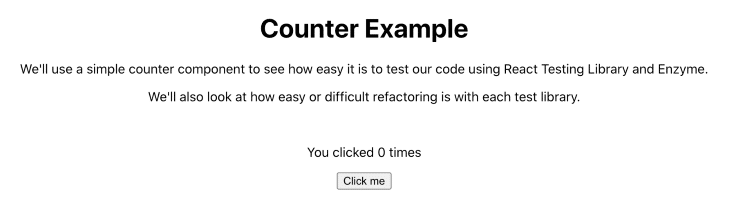

First, we will create a simple counter app, as seen below. Our app will contain some introduction text followed by a message displaying how many times the button has been clicked. Below, we will include the button.

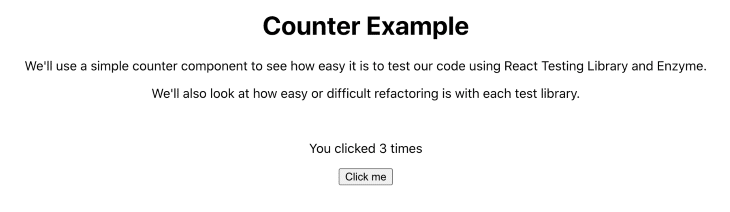

Each time the user clicks the button, the counter increments, and so does the message text on the screen. You can see this in the image below.

Simple enough, right? Here’s the JavaScript needed to implement this component:

import React, { Component } from 'react';

import './App.css';

class App extends Component {

state = {

count: 0,

}

handleClick = () => {

this.setState(prevState => ({ count: prevState.count + 1 }))

}

render() {

return (

<main className="App">

<h1>Counter Example</h1>

<p>We'll use a simple counter component to see how easy it is to test our code using React Testing Library and Enzyme.</p>

<p>We'll also look at how easy or difficult refactoring is with each test library.</p>

<br />

<p id="output">You clicked {this.state.count} times</p>

<button onClick={this.handleClick}>

Click me

</button>

</main>

);

}

}

export default App;

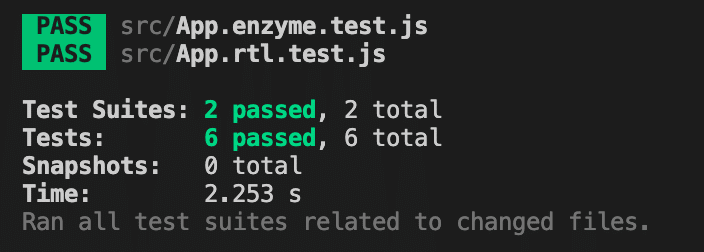

To make sure our counter is functioning properly, I’ve written tests that I run with Jest. Our test suite contains two files: one written using React Testing Library and one written using Enzyme.

The React Testing Library tests look like this:

import { fireEvent, render, screen } from '@testing-library/react';

import App from './App';

describe('App', () => {

it('renders the header text, the click count, and a button', () => {

render(<App />);

expect(screen.getByText('Counter Example')).toBeInTheDocument();

expect(screen.getByText('You clicked 0 times')).toBeInTheDocument();

expect(screen.getByText('Click me')).toBeInTheDocument();

});

it('increments the counter when clicked', () => {

render(<App />);

expect(screen.getByText('You clicked 0 times')).toBeInTheDocument();

fireEvent.click(screen.getByText('Click me'));

expect(screen.getByText('You clicked 1 times')).toBeInTheDocument();

});

});

You can see that we check for the presence of essential text on the page in the first test and how we test the behavior of clicking the button in the second test. These tests focus on what the user can see and how they can interact with the app.

On the other hand, the Enzyme tests look like this:

import { shallow } from 'enzyme';

import App from './App';

describe('App', () => {

it('renders the header text, the click count, and a button', () => {

const wrapper = shallow(<App />);

expect(wrapper.find('h1').text()).toEqual('Counter Example');

expect(wrapper.find('#output').text()).toEqual('You clicked 0 times');

expect(wrapper.find('button').text()).toEqual('Click me');

});

it('increments the counter when the handleClick method is called', () => {

const wrapper = shallow(<App />);

expect(wrapper.find('#output').text()).toEqual('You clicked 0 times');

wrapper.instance().handleClick();

expect(wrapper.find('#output').text()).toEqual('You clicked 1 times');

});

it('updates the output message in the UI when the count state is changed', () => {

const wrapper = shallow(<App />);

expect(wrapper.find('#output').text()).toEqual('You clicked 0 times');

wrapper.setState({ count: 1 });

expect(wrapper.find('#output').text()).toEqual('You clicked 1 times');

});

it('increments the counter when clicked', () => {

const wrapper = shallow(<App />);

expect(wrapper.find('#output').text()).toEqual('You clicked 0 times');

wrapper.find('button').simulate('click');

expect(wrapper.find('#output').text()).toEqual('You clicked 1 times');

});

});

Note that the Enzyme tests take a different approach. Instead of focusing on the end user experience, these tests fixate more on the implementation details.

For example, they target the output message by the paragraph’s id attribute. They even directly manipulate the component’s state count value and directly call the button’s handleClick method in some of the tests.

These are not things that a user can do (unless of course they are a developer playing around with their browser’s developer tools!).

If we run these tests, we will see that all six tests pass. They even give us 100% code coverage. Nice!

To be clear, we’re duplicating test coverage to some extent by writing two separate test files for a single component. In reality, a codebase would generally choose one testing library or the other, either React Testing Library or Enzyme.

The choice of library would then highly influence the testing strategy and how tests are written. But, using these two testing libraries side by side will allow us to observe some interesting trends as we make changes to our app.

For those following along, all of the code for this counter app can be found on Github.

Now that we’ve introduced the app and verified that it works, we’re ready to do some refactoring! It’s important to note that all of these refactors will change implementation details only – the actual functionality and behavior of the app will remain the same.

Our first refactor will change the component’s state property count to counterValue. With this simple naming change, our source code now looks like this:

import React, { Component } from 'react';

import './App.css';

class App extends Component {

state = {

counterValue: 0,

}

handleClick = () => {

this.setState(prevState => ({ counterValue: prevState.counterValue + 1 }))

}

render() {

return (

<main className="App">

<h1>Counter Example</h1>

<p>We'll use a simple counter component to see how easy it is to test our code using React Testing Library and Enzyme.</p>

<p>We'll also look at how easy or difficult refactoring is with each test library.</p>

<br />

<p id="output">You clicked {this.state.counterValue} times</p>

<button onClick={this.handleClick}>

Click me

</button>

</main>

);

}

}

export default App;

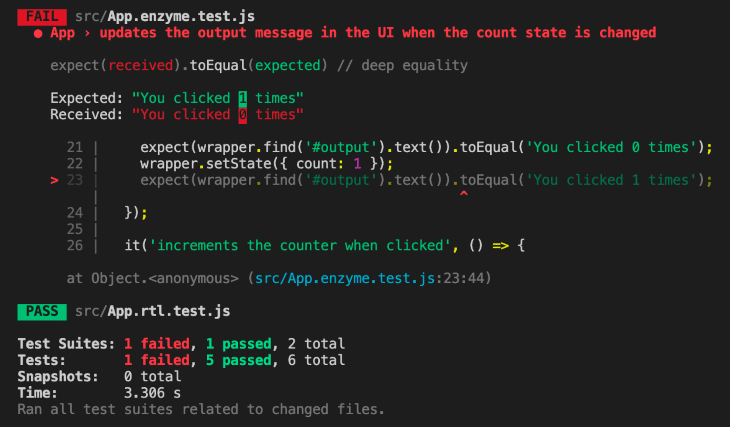

Let’s see what happens when we run our test suite:

Oh no! One of our tests failed! Did we break something in our app? A quick manual check in our user interface confirms for us that our app is in fact working fine. So what happened?

If you look at the test output above, you’ll see that line 22 of our Enzyme test file directly modifies the component state to have a value of { count: 1 }. That would have worked before, but remember that when we refactored our property name, we changed it from count to counterValue. To get the test to pass, we can update our test like so:

it('updates the output message in the UI when the count state is changed', () => {

const wrapper = shallow(<App />);

expect(wrapper.find('#output').text()).toEqual('You clicked 0 times');

wrapper.setState({ counterValue: 1 });

expect(wrapper.find('#output').text()).toEqual('You clicked 1 times');

});

That’s better.

Let’s make another simple change. In this refactoring example, we will rename the click handler method from handleClick to incrementCounter. Our app code now looks like this:

import React, { Component } from 'react';

import './App.css';

class App extends Component {

state = {

counterValue: 0,

}

incrementCounter = () => {

this.setState(prevState => ({ counterValue: prevState.counterValue + 1 }))

}

render() {

return (

<main className="App">

<h1>Counter Example</h1>

<p>We'll use a simple counter component to see how easy it is to test our code using React Testing Library and Enzyme.</p>

<p>We'll also look at how easy or difficult refactoring is with each test library.</p>

<br />

<p id="output">You clicked {this.state.counterValue} times</p>

<button onClick={this.incrementCounter}>

Click me

</button>

</main>

);

}

}

export default App;

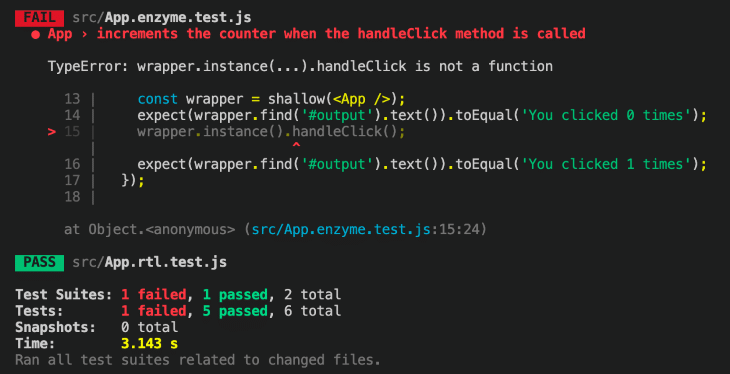

After making this change, we can run our tests again:

Another test failure! Hmmm… but our app is still working properly when we check the UI again. Sound familiar?

This time it’s our Enzyme test complaining that handleClick is not a function, which makes sense because we changed that method name to incrementCounter. Now we can update that in our test:

it('increments the counter when the handleClick method is called', () => {

const wrapper = shallow(<App />);

expect(wrapper.find('#output').text()).toEqual('You clicked 0 times');

wrapper.instance().incrementCounter();

expect(wrapper.find('#output').text()).toEqual('You clicked 1 times');

});

As expected, our tests are passing again.

Let’s look at one more example. The paragraph element that holds our output message currently has an ID attribute with a value of output. We are going to change that value to clickCountMessage instead. The app code now looks like this:

import React, { Component } from 'react';

import './App.css';

class App extends Component {

state = {

counterValue: 0,

}

incrementCounter = () => {

this.setState(prevState => ({ counterValue: prevState.counterValue + 1 }))

}

render() {

return (

<main className="App">

<h1>Counter Example</h1>

<p>We'll use a simple counter component to see how easy it is to test our code using React Testing Library and Enzyme.</p>

<p>We'll also look at how easy or difficult refactoring is with each test library.</p>

<br />

<p id="clickCountMessage">You clicked {this.state.counterValue} times</p>

<button onClick={this.incrementCounter}>

Click me

</button>

</main>

);

}

}

export default App;

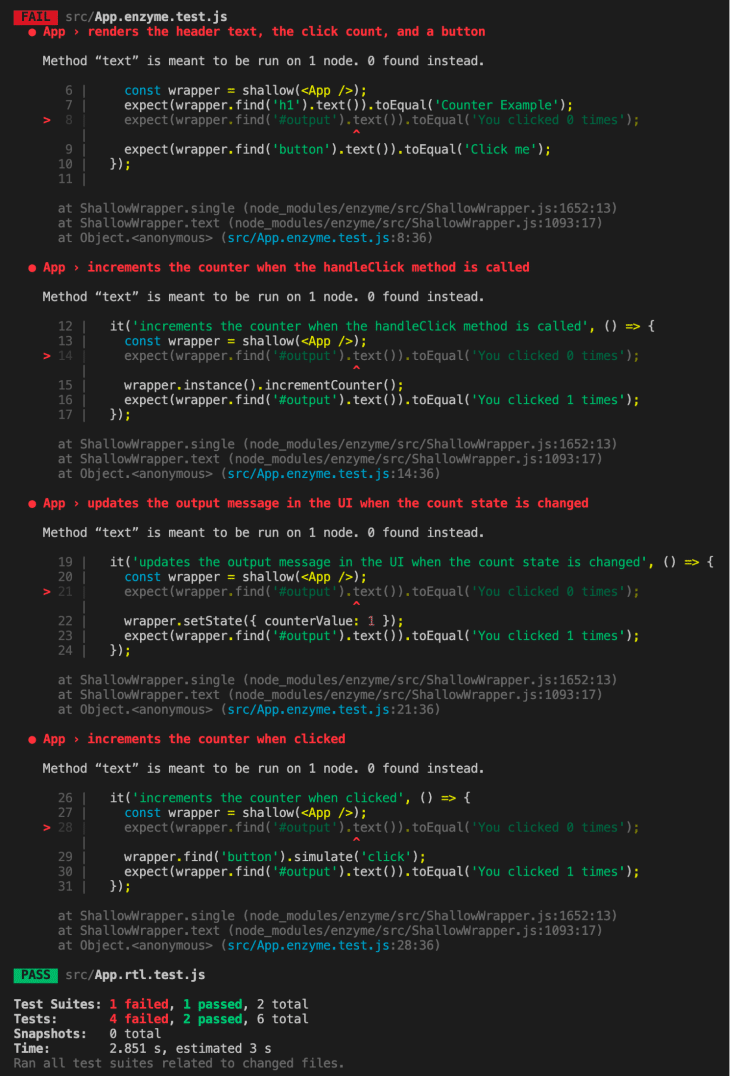

And let’s run our tests once more. Can you guess what’s going to happen?

Failure! All four of our Enzyme tests have failed because they each rely on the presence of an element that can be selected with the #output CSS selector. But with our change to the element’s ID, the proper CSS selector is now #clickCountMessage. Let’s update our tests to reflect that change:

import { shallow } from 'enzyme';

import App from './App';

describe('App', () => {

it('renders the header text, the click count, and a button', () => {

const wrapper = shallow(<App />);

expect(wrapper.find('h1').text()).toEqual('Counter Example');

expect(wrapper.find('#clickCountMessage').text()).toEqual('You clicked 0 times');

expect(wrapper.find('button').text()).toEqual('Click me');

});

it('increments the counter when the handleClick method is called', () => {

const wrapper = shallow(<App />);

expect(wrapper.find('#clickCountMessage').text()).toEqual('You clicked 0 times');

wrapper.instance().incrementCounter();

expect(wrapper.find('#clickCountMessage').text()).toEqual('You clicked 1 times');

});

it('updates the clickCountMessage message in the UI when the count state is changed', () => {

const wrapper = shallow(<App />);

expect(wrapper.find('#clickCountMessage').text()).toEqual('You clicked 0 times');

wrapper.setState({ counterValue: 1 });

expect(wrapper.find('#clickCountMessage').text()).toEqual('You clicked 1 times');

});

it('increments the counter when clicked', () => {

const wrapper = shallow(<App />);

expect(wrapper.find('#clickCountMessage').text()).toEqual('You clicked 0 times');

wrapper.find('button').simulate('click');

expect(wrapper.find('#clickCountMessage').text()).toEqual('You clicked 1 times');

});

})

There we go. Now everything is back to normal. What a relief!

If you’ve been paying attention, you’ll notice a few patterns in all of our test failures.

First, the only tests that failed were tests that were part of our Enzyme test suite. You’ll remember that this is because the Enzyme tests focus on implementation details while the React Testing Library tests focus on the user experience.

Second, even when we had test failures, the app was still working fine. This lowers our confidence in our tests. When a test fails, we have to wonder, “Is something actually wrong, or do we just have a test that needs updating?”

Third, it’s a huge pain to update our tests just because we renamed a variable or a function. Wouldn’t it be nice if our tests didn’t concern themselves with these kinds of implementation details?

The good news is that there is a better way. In fact, that’s the core philosophy behind React Testing Library: “The more your tests resemble the way your software is used, the more confidence they can give you.”

By writing tests that focus on what users can see and do, we can develop a more reliable test suite. We save ourselves hours of time spent debugging brittle tests, and we can successfully refactor our apps with confidence.

Install LogRocket via npm or script tag. LogRocket.init() must be called client-side, not

server-side

$ npm i --save logrocket

// Code:

import LogRocket from 'logrocket';

LogRocket.init('app/id');

// Add to your HTML:

<script src="https://cdn.lr-ingest.com/LogRocket.min.js"></script>

<script>window.LogRocket && window.LogRocket.init('app/id');</script>

Solve coordination problems in Islands architecture using event-driven patterns instead of localStorage polling.

Signal Forms in Angular 21 replace FormGroup pain and ControlValueAccessor complexity with a cleaner, reactive model built on signals.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the February 25th issue.

Explore how the Universal Commerce Protocol (UCP) allows AI agents to connect with merchants, handle checkout sessions, and securely process payments in real-world e-commerce flows.

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now