The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

Like a lot of developers, I like to use my blog as a personal playground to try out the latest technologies. My blog was written in Gatsby, but recently I migrated it to Next.js. In this post, I’m going to talk about my experience, what went well, and what didn’t.

Keep in mind that, while Gatsby and Next.js do have an overlap in functionality, these two tools are vastly different in their feature set, problems they solve, and their philosophy. If you’re interested in a comprehensive comparison between these two frameworks, I suggest reading Next.js vs. GatsbyJS: A developer’s perspective.

Note that since that post was published, both tools have received lots of great updates, especially Next.js, so be sure to check out Gatbsy’s changelog and Next.js blog.

The reason why I started using Gatsby in the first place was because of the way I wanted to author my code and the design I wanted to achieve required more control over the build process.

The problem with blogging tools is that, while they provide a lot of features out of the box, they only offer so much flexibility, so for features that weren’t included I had to keep convincing myself that I didn’t really need them, but I wanted my only constraint to be what I have time for, not what my tool supports.

Among other things, I wanted to group multiple posts into a series of posts, add a fuzzy search bar for finding posts easily, and use MDX to insert custom pieces of functionality into my posts that markdown didn’t support. Ideally, I wanted to author my blog as a React application, but build it as a static website that wouldn’t depend on JavaScript.

Initially, I tried using Next.js, but it was still at v4.1.4 at the time, compared to v9.3 at the time of writing this post, and it didn’t have all the features I needed, like static export, so I continued searching.

Eventually, Gatsby caught my attention, and, over time, I managed to build my blog with it. However, learning Gatsby wasn’t easy.

I was completely new to GraphQL itself, not to mention Gatsby’s programmatic approach to building websites, it was a huge learning curve for me. Through lots of practice I got comfortable with Gatsby, and, ultimately, it gave me what I desperately wanted — to be able to author my blog as a React application.

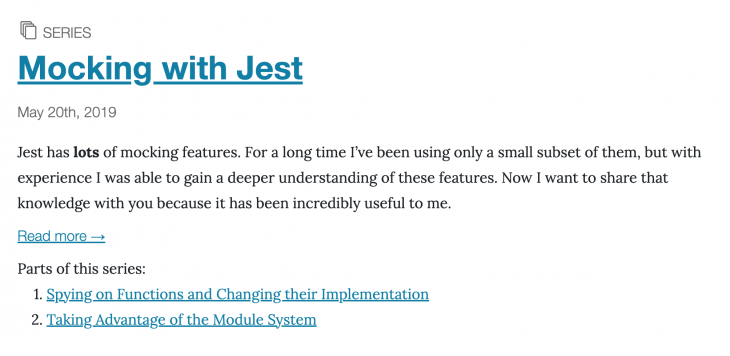

While Gatsby’s programmatic approach to extracting data and building pages seemed somewhat indirect to me, I couldn’t deny how powerful it was, I could do pretty much anything I wanted with it, for the first time I wasn’t bound by the tool. One of the features I added is combining related posts into series, so I can display separate parts like this:

My gatsby-node.js has only 200 lines of code and it has all kinds of features, like languages, categories, pagination, post series, drafts, I can even add Netlify redirects programmatically!

There are lots of Gatsby plugins out there that can perform quite interesting tasks, I even built a few myself. This ecosystem allowed me to easily build a sitemap and a feed for my blog.

However, my main pain point of Gatsby is GraphQL, especially combined with type checking. I often had to write large queries, then write types for them if I wanted some kind of type safety, repeating the same data structure, then access all this deeply nested data, often using destructing to make it easier… I never got entirely used to it, it always felt verbose.

Even though I managed to implement every feature I wanted, I started wishing for a more minimal alternative that would help me work faster. That’s when I started noticing Next.js, which just updates in v9.3, including static site generation.

From the developer’s perspective, Next.js is much easier to start with. However, migrating all of that logic was quite a challenge, I had to make a lot of changes to adapt to this new environment, but the main challenge was definitely MDX. When I was using Gatsby my blog posts were in a separate directory, where they were processed with Gatsby’s MDX plugin. That way their data was available through GraphQL to be output anywhere — frontmatter, exported values, body, etc. I also attached my own custom fields to it, like URL and various data about series. This gave me a lot of control over output.

Next.js also has an official MDX plugin, but all it does is add the Webpack loader, while Gatsby’s MDX plugin does much, much more. At first, I thought that this would be achievable in Next.js with dynamic routes and static site generation for markdown because it can be compiled to static HTML at build time, but MDX is a different kind of format: while it may seem like a superset of Markdown, it’s actually a superset of JSX because it compiles to a React component, and it supports modules and custom components, so MDX files should be treated like all other components. This meant that I had to put my posts in the pages directory, so there was no way to add behavior like default layout, or list posts. Or was there?

The official Next.js plugin for MDX isn’t the only one out there, there are more, some specifically optimized for blogs. The most popular alternative is next-mdx-enhanced, which supports default layout and frontmatter. If this is all you need, then bingo! Now only listing posts remain.

If all you need is to extract frontmatter data like title, published date and link to the post, you can do so by traversing through the filesystem in getStaticProps, computing the URL from the file path and using a tool like gray-matter to extract the frontmatter.

However, I didn’t want to sacrifice any of the features I had with Gatsby, so I had to get creative. I knew that it would take me too long to understand and attempt to replicate all of the logic from Gatsby’s MDX plugin, but I wanted to learn about it as much as I could to gain some inspiration, which led me to start diving more into the unified ecosystem.

Over time I realized I could hack my MDX files by creating custom remark and retype plugins to edit the content, which is what Gatsby’s plugin does as well, among other things. I could add export statements for layout, JSX excerpt, data about series… all through editing the AST.

Going into all of those features could be a separate post, so I’m just going give you an example; this is a simplified version of a remark plugin I wrote to add a default layout to my posts:

const u = require('unist-builder')

const defaultLayout = ({ importFrom }) => (tree) => {

tree.children.unshift(

u('import', `import DefaultLayout from ${JSON.stringify(importFrom)}`),

)

tree.children.push(

u('export', {

default: true,

value: `export default DefaultLayout`,

}),

)

}

module.exports = defaultLayout

I added it to remarkPlugins when applying the MDX plugin in next.config.js:

const defaultLayout = require('./plugins/remark-mdx-default-layout')

const withMdx = require('@next/mdx')({

remarkPlugins = [

[defaultLayout, { importFrom: '../../components/DefaultLayout' })],

],

})

module.exports = withMdx({

pageExtensions: ['js', 'jsx', 'mdx'],

})

Quite simple, isn’t it?

Listing posts was a separate challenge. At first, it seemed like it could be done in getStaticProps, but it’s not possible to import modules there, which is the only way to access exported metadata, and maintaining a list of import statements for every post is not scalable. However, there is a middle ground. Generating those import statements with babel-plugin-codegen.

The benefit of this plugin is a little hard to figure out at first, which is why a real-world use case like this is the best way to understand. This is the code I was aiming for:

import * as PostOne from './posts/one' import * as PostTwo from './posts/two' import * as PostThree from './posts/three' // ... const posts = [ PostOne, PostTwo, PostThree, // ... ]

I’m using namespace imports (with * as) so I can access all of the metadata exported from posts.

I generated this code by first adding babel-plugin-codegen to my babel configuration:

module.exports = {

presets: ['next/babel'],

plugins: ['codegen'],

}

Then I wrote a script which generates the aforementioned code:

const fs = require('fs')

const path = require('path')

const posts = fs.readdirSync(path.join(process.cwd(), 'pages/posts'))

const importStatements = []

const importNames = []

let result = ''

posts.forEach((post, index) => {

importStatements.push(`import * as Post${index + 1} from './posts/${path.basename(post, '.mdx')}'`)

importNames.push(`Post${index + 1}`)

})

result += importStatements.join('\n')

result += '\n\n'

result += `const posts = [${importNames.join(', ')}]`

module.exports = result

Finally, I imported the script using a babel-plugin-codegen’s import comment:

import /* codegen */ posts from '../codegen/posts-list'

Now I could render the list of my posts however I wanted, for example:

<ul>

{posts.map(({ frontmatter, path }) => (

<li key={path}>

<Link href={path}>{frontmatter.title}</Link>

</li>

))}

</ul>

Of course, you’ll want to order them by the published date.

The last two problems I wanted to solve are the sitemap and the feed.

For generating the sitemap I found nextjs-sitemap-generator, which did the job quite well and was really easy to use:

const sitemap = require('nextjs-sitemap-generator')

const path = require('path')

await sitemap({

baseUrl: 'https://silvenon.com',

ignoreIndexFiles: true,

pagesDirectory: path.join(process.cwd(), 'out'),

targetDirectory: path.join(process.cwd(), 'out'),

})

Generating the feed required more work. Fortunately, I could reuse a lot of functionality for extracting metadata from my posts, and use the feed package to create the feed. Here’s an example of adding a feed, leaving out the logic for extracting metadata for the sake of brevity:

const feed = require('feed')

posts.forEach(({ frontmatter, path, excerpt }) => {

feed.addItem({

title: frontmatter.title,

id: `https://silvenon.com${path}`,

link: `https://silvenon.com${path}`,

description: excerpt,

author: [

{

name: 'Matija Marohnić',

email: '[email protected]',

link: 'https://silvenon',

},

],

date: new Date(frontmatter.published),

})

})

Read feeds readme for complete instructions for creating a feed.

Blogs are a specific type of website, in some aspects simpler, in others, they can be fairly complicated, especially my blog. Choosing the right tool for the job is often difficult because without experience it’s hard to accurately evaluate whether the tool will work in practice, this is why it’s good to read about the options before actually trying it out.

However, using Next.js for static exporting is still fairly new, especially considering that key features landed just months ago, so I was curious whether I could pull it off. MDX proved to be the only seemingly insurmountable obstacle to overcome because the ecosystem is just not ready yet, but there are many great things coming in MDX v2 which might solve most of the problems I was having, so keep an eye out for that!

Debugging Next applications can be difficult, especially when users experience issues that are difficult to reproduce. If you’re interested in monitoring and tracking state, automatically surfacing JavaScript errors, and tracking slow network requests and component load time, try LogRocket.

LogRocket captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings from user sessions and lets you replay them as users saw it, eliminating guesswork around why bugs happen — compatible with all frameworks.

LogRocket's Galileo AI watches sessions for you, instantly identifying and explaining user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

The LogRocket Redux middleware package adds an extra layer of visibility into your user sessions. LogRocket logs all actions and state from your Redux stores.

Modernize how you debug your Next.js apps — start monitoring for free.

Compare the top AI development tools and models of March 2026. View updated rankings, feature breakdowns, and find the best fit for you.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the March 11th issue.

Buying AI tools isn’t enough. Engineering teams need AI literacy programs to unlock real productivity gains and avoid uneven adoption.

If your AI app or agent works perfectly in development but falls apart in production, you’re not alone. In a […]

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now