As with any conversation about performance, we need to gain some shared context around the type of JavaScript code we want to optimize and the context in which it will run. So, let’s start with some definitions:

Performance. First of all, when we use the word performance in the context of a computer program, we are referring to how quickly or efficiently that program can execute.

Polymorphic functions. A polymorphic function is a function that changes its behavior based on the types of arguments that are passed to it.

The key word here is types, as opposed to values. (A function that didn’t change its output based on different values for arguments would not be a very useful function at all.)

JavaScript engine. In order to think about performance productively, we also need to know where our JavaScript is going to be executed. For our example code, we’ll use the V8 engine given its popularity.

V8 is the engine that powers the Chrome browser, Node.js, the Edge browser, and more. Note that there are also other JavaScript engines with their own performance characteristics, such as SpiderMonkey (used by Firefox), JavaScriptCore (used by Safari), and others.

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

Suppose we are building a JavaScript library that enables other engineers to easily store messages to an in-memory database with our simple API. In order to make our library as easy and comfortable to use as possible, we provide a single polymorphic function that is very flexible with the arguments that it receives.

The first signature of our function will take the required data as three separate arguments, and can be called like this:

saveMessage(author, contents, timestamp);

options objectThis signature will allow consumers to separate the required data (message contents) from the optional data (the author and the timestamp) into two separate arguments. We’ll accept the arguments in any order, for convenience.

saveMessage(contents, options); saveMessage(options, contents);

options objectWe’ll also allow users of our API to call the function passing in a single argument of an object containing all of the data we need:

saveMessage(options);

Finally, we’ll allow users of our API to provide only the message contents, and we’ll provide default values for the rest of the data:

saveMessage(contents);

OK, with our API defined, we can build the implementation of our polymorphic function.

// We'll utilize an array for a simple in-memory database.

const database = [];

function saveMessage(...args) {

// Once we get our input into a unified format, we'll use this function to

// store it on our database and calculate an identifier that represents the

// data.

function save(record) {

database.push(record);

let result = '';

for (let i = 0; i < 5_000; i += 1) {

result += record.author + record.contents;

}

return result.length;

}

// If the developer has passed us all the data individually, we'll package

// it up into an object and store it in the database.

if (args.length === 3) {

const [author, contents, timestamp] = args;

return save({author, contents, timestamp});

}

// Or, if the developer has provided a message string and an options object,

// we'll figure out which order they came in and then save appropriately.

if (args.length === 2) {

if (typeof args[0] === 'string') {

const [contents, options] = args;

const record = {author: options.author, contents, timestamp: options.timestamp};

return save(record);

} else {

const [options, contents] = args;

const record = {author: options.author, contents, timestamp: options.timestamp};

return save(record);

}

}

// Otherwise, we've either gotten a string message or a complete set of

// options.

if (args.length === 1) {

const [arg] = args;

if (typeof arg === 'string') {

// If the single argument is the string message, save it to the database

// with some default values for author and timestamp.

const record = {

author: 'Anonymous',

contents: arg,

timestamp: new Date(),

};

return save(record);

} else {

// Otherwise, just save the options object in the database as-is.

return save(arg);

}

}

}

OK, now we’ll write some code that stores a lot of messages using our function — taking advantage of its polymorphic API — and measure its performance.

const { performance } = require('perf_hooks');

const start = performance.now();

for (let i = 0; i < 5_000; i++) {

saveMessage(

'Batman',

'Why do we fall? So we can learn to pick ourselves back up.',

new Date(),

);

saveMessage(

'Life doesn\'t give us purpose. We give life purpose.',

{

author: 'The Flash',

timestamp: new Date(),

},

);

saveMessage(

'No matter how bad things get, something good is out there, over the horizon.',

{},

);

saveMessage(

{

author: 'Uncle Ben',

timestamp: new Date(),

},

'With great power comes great responsibility.',

);

saveMessage({

author: 'Ms. Marvel',

contents: 'When you decide not to be afraid, you can find friends in super unexpected places.',

timestamp: new Date(),

});

saveMessage(

'Better late than never, but never late is better.'

);

}

console.log(`Inserted ${database.length} records into the database.`);

console.log(`Duration: ${(performance.now() - start).toFixed(2)} milliseconds`);

Now let’s implement our function again but with a simpler, monomorphic API.

In exchange for a more restrictive API, we can trim down the complexity of our function and make it monomorphic, meaning that the arguments of the function are always of the same type and in the same order.

Although it won’t be as flexible, we can keep some of the ergonomics of the previous implementation by utilizing default arguments. Our new function will look like this:

// We'll again utilize an array for a simple in-memory database.

const database = [];

// Rather than a generic list of arguments, we'll take the message contents and

// optionally the author and timestamp.

function saveMessage(contents, author = 'Anonymous', timestamp = new Date()) {

// First we'll save our record into our database array.

database.push({author, contents, timestamp});

// As before, we'll calculate and return an identifier that represents the

// data, but we'll inline the contents of the function since there's no need

// to re-use it.

let result = '';

for (let i = 0; i < 5_000; i += 1) {

result += author + contents;

}

return result.length;

}

We’ll update the performance measuring code from our previous example to use our new unified API.

const { performance } = require('perf_hooks');

const start = performance.now();

for (let i = 0; i < 5_000; i++) {

saveMessage(

'Why do we fall? So we can learn to pick ourselves back up.',

'Batman',

new Date(),

);

saveMessage(

'Life doesn\'t give us purpose. We give life purpose.',

'The Flash',

new Date(),

);

saveMessage(

'No matter how bad things get, something good is out there, over the horizon.',

);

saveMessage(

'With great power comes great responsibility.',

'Uncle Ben',

new Date(),

);

saveMessage(

'When you decide not to be afraid, you can find friends in super unexpected places.',

'Ms. Marvel',

new Date(),

);

saveMessage(

'Better late than never, but never late is better.'

);

}

console.log(`Inserted ${database.length} records into the database.`);

console.log(`Duration: ${(performance.now() - start).toFixed(2)} milliseconds`);

OK, now let’s run our programs and compare the results.

$ node polymorphic.js Inserted 30000 records into the database. Duration: 6565.41 milliseconds $ node monomorphic.js Inserted 30000 records into the database. Duration: 2955.01 milliseconds

The monomorphic version of our function is about twice as fast as the polymorphic version, as there is less code to execute in the monomorphic version. But because the types and shapes of the arguments in the polymorphic version vary widely, V8 has a more difficult time making optimizations to our code.

In simple terms, when V8 can identify (a) that we call a function frequently, and (b) that the function gets called with the same types of arguments, V8 can create “shortcuts” for things like object property lookups, arithmetic, string operations, and more.

For a deeper look at how these “shortcuts” work I would recommend this article: What’s up with monomorphism? by Vyacheslav Egorov.

Before you go off optimizing all of your code to be monomorphic, there are a few important points to consider first.

Polymorphic function calls are not likely to be your performance bottleneck. There are many other types of operations that contribute much more commonly to performance problems, like latent network calls, moving large amounts of data around in memory, disk i/o, complex database queries, to name just a few.

You will only run into performance issues with polymorphic functions if those functions are very, very “hot” (frequently run). Only highly specialized applications, similar to our contrived examples above, will benefit from optimization at this level. If you have a polymorphic function that runs only a few times, there will be no benefit from rewriting it to be monomorphic.

You will have more luck updating your code to be efficient rather than trying to optimize for the JavaScript engine. In most cases, applying good software design principles and paying attention to the complexity of your code will take you further than focusing on the underlying runtime. Also, V8 and other engines are constantly getting faster, so some performance optimizations that work today may become irrelevant in a future version of the engine.

Polymorphic APIs can be convenient to use due to their flexibility. In certain situations, they can be more expensive to execute, as JavaScript engines cannot optimize them as aggressively as simpler, monomorphic functions.

In many cases, however, the difference will be insignificant. API patterns should be based on other factors like legibility, consistency, and maintainability because performance issues are more likely to crop up in other areas anyway. Happy coding!

Debugging code is always a tedious task. But the more you understand your errors, the easier it is to fix them.

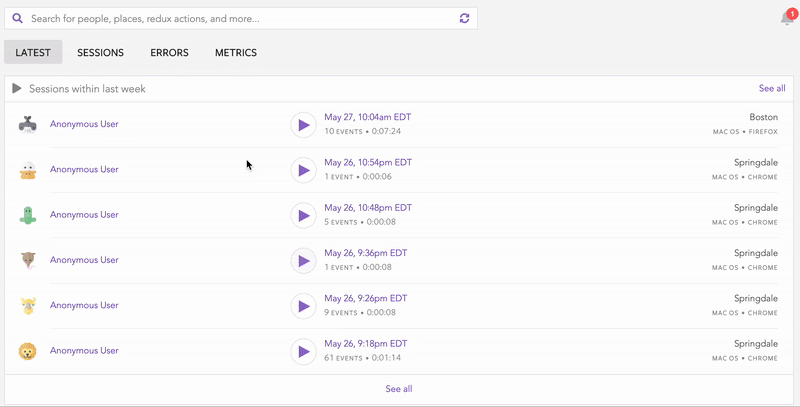

LogRocket allows you to understand these errors in new and unique ways. Our frontend monitoring solution tracks user engagement with your JavaScript frontends to give you the ability to see exactly what the user did that led to an error.

LogRocket records console logs, page load times, stack traces, slow network requests/responses with headers + bodies, browser metadata, and custom logs. Understanding the impact of your JavaScript code will never be easier!

Solve coordination problems in Islands architecture using event-driven patterns instead of localStorage polling.

Signal Forms in Angular 21 replace FormGroup pain and ControlValueAccessor complexity with a cleaner, reactive model built on signals.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the February 25th issue.

Explore how the Universal Commerce Protocol (UCP) allows AI agents to connect with merchants, handle checkout sessions, and securely process payments in real-world e-commerce flows.

Would you be interested in joining LogRocket's developer community?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

One Reply to "How polymorphic JavaScript functions affect performance"

The overloading of a function is only one type of polymorphism. Javascript does not support overloading. One this function breaks SOLID principles on so many different levels. Two this function should never have made it past code review. Polymorphism is a good thing. It allows robust, reusable and maintainable code. You cannot write bad code much less in one example to discredit an entire paradigm. Good writing, but monomorphic functions are not the future. By creating a one to one mapping between types and return statements we eliminate robustness in the code base and increase the amount of code we have to write. Without polymorphism we don’t have templates, or generics. Code becomes static. Hence useless beyond the current use case.