JavaScript is a widely adopted language that you can use to build anything from a simple landing page to a production-grade, full-stack application. As JavaScript and programming in general evolved, developers came to realize that the object-oriented programming (OOP) paradigm is undesirable for most use cases. Functional programming emerged as the solution to many of the pain points associated with OOP.

Closures are a widely discussed topic in the world of functional programming, but they’re often defined loosely and in technical jargon. We’ll do our best here to explain how JavaScript closures work in layman’s terms.

By the end of this tutorial, you should understand:

We’ll start by showing what a closure looks like.

function makeCounter() {

let count = 0;

return function increment() {

count += 1;

return count;

};

};

const countIncrementor = makeCounter();

countIncrementor(); // returns 1

countIncrementor(); // returns 2

Try running the code on your own. Technically, the function named makeCounter returns another function called increment. This increment function has access to the count variable even after the makeCount function has been executed. Part of the closure here is the count variable; it’s available to the increment function when it’s defined, even after makeCounter finishes up. The other part is the increment function.

Imagine you have a house and a garden that surrounds it. Once you open the door to the garden and close it, you can’t open it again — the garden becomes inaccessible. You’re hungry and, fortunately, there’s an orange tree and an apple tree in your garden. You take a small bag, pluck an orange and an apple, and go back inside your house. Remember, you can’t go back out again.

Now, once you’re inside your house, you can take the orange or the apple out of the bag and eat it whenever you get hungry again. The small bag in this example is the closure. A closure contains all the variables and functions that were available to you when you were in the garden, even when you’re inside the house and can’t go outside again.

Let’s see how this plays out in code:

function makeFruitGarden() {

let fruits = ['apple', 'orange'];

return function() {

return fruits.pop();

};

};

const consumeFruit = makeFruitGarden();

consumeFruit(); // returns orange

consumeFruit(); // returns apple

Since the fruits variable is available to the returned function when makeFruitGarden is executed, the fruits variable and the inner function become the closure. Whenever consumeFruit is executed, a fruit — the last element from the fruits array because pop() is being used — is returned. Once both fruits have been consumed/eaten, there’ll be nothing to left to eat.

To truly understand closures, you should be familiar with the term “scope.” Lexical scope is a fancy term for the current environment relative to whatever you’re referring to.

In the following example, the scope of the variable named myName is called the “global scope”.

// global scope const myName = "John Doe" function displayName() { // local/function scope console.log(myName); }; displayName()

You may have seen this concept referenced when reading about how var is not block-scoped and how const/let is. It’s important to note that in JavaScript, a function always creates its own scope. This is called the local or function scope, as shown in the code example.

If you’ve been paying attention, you might be thinking that myName and displayName are part of a closure. You’d be correct! But since the function and the variable here exist in the global scope, there’s not much value in calling it a closure.

There are many types of scopes in JavaScript, but when it comes to closures, there are three scopes you should know:

Now let’s dive into some use cases.

Function currying is another powerful concept in functional programming. To implement a curried function in JavaScript, you would use closures.

Currying a function can be described as transforming a function and is executed like this: add(1, 2, 3) to add(1)(2)(3).

function add(a) {

return function(b) {

return function(c) {

return a + b + c;

};

};

};

add(1)(2)(3) // returns 6

The add function takes a single argument and then returns two functions that are nested in one after the other. The goal of currying is to take a bunch of arguments and eventually end up with a single value.

The goal of a higher-order function is to take a function as an argument and return a result. Array methods such as map and reduce are examples of higher-order functions.

const arrayOfNumbers = [1, 2, 3];

const displayNumber = (num) => {

console.log(num);

}

arrayOfNumbers.forEach(displayNumber)

The Array.prototype.forEach higher-order function here accepts displayNumber as an argument and then executes it for each element in the arrayOfNumbers. If you’ve used a UI framework such as Vue or React, you might be familiar with higher-order components, which are essentially the same thing as higher-order functions.

So what’s the difference is between higher-order functions and currying? While a higher-order function takes a function as an argument returns a value, a curried function returns a function as a result, which eventually leads to a value.

This is a common design pattern often used to get and set properties of DOM elements. In the following example, we’ll make an element manager to style elements.

function makeStyleManager(selector) {

const element = document.querySelector(selector);

const currentStyles = {...window.getComputedStyle(element)};

return {

getStyle: function(CSSproperty) {

return currentStyles[CSSproperty];

},

setStyle: function(CSSproperty, newStyle) {

element.style[CSSproperty] = newStyle;

},

};

};

const bodyStyleManager = makeStyleManager('body');

bodyStyleManager.getStyle('background-color'); // returns rgb(0,0,0)

bodyStyleManager.setStyle('background-color', 'red'); // sets bg color to red

makeStyleManager returns an object that gives access to two functions, which are part of a closure alongside the element and currentStyles variables. Even after makeStyleManager has finished executing, the getStyle and setStyle functions have access to the variables.

JavaScript closures can be difficult to understand, even for developers with professional experience under their belt. Understanding closures will ultimately make you a better developer.

You should now be able to identify a closure when it’s being used in a codebase that looks weird or doesn’t make sense. Closures are a critical concept in functional programming and I hope this guide helped you take a step forward in your journey toward mastering it.

Debugging code is always a tedious task. But the more you understand your errors, the easier it is to fix them.

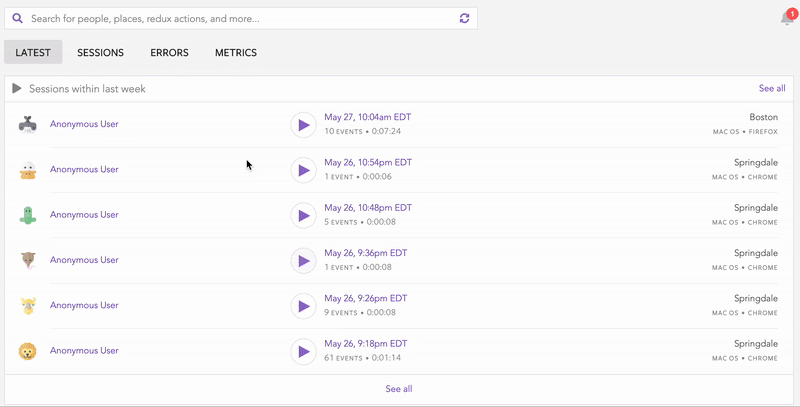

LogRocket allows you to understand these errors in new and unique ways. Our frontend monitoring solution tracks user engagement with your JavaScript frontends to give you the ability to see exactly what the user did that led to an error.

LogRocket records console logs, page load times, stack traces, slow network requests/responses with headers + bodies, browser metadata, and custom logs. Understanding the impact of your JavaScript code will never be easier!

ExecutionContext, call stack, lexical environment, etc.Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

Get to know RxJS features, benefits, and more to help you understand what it is, how it works, and why you should use it.

Explore how to effectively break down a monolithic application into microservices using feature flags and Flagsmith.

Native dialog and popover elements have their own well-defined roles in modern-day frontend web development. Dialog elements are known to […]

LlamaIndex provides tools for ingesting, processing, and implementing complex query workflows that combine data access with LLM prompting.