These days, you have to use a module bundler like webpack to benefit from a development workflow that utilizes state-of-the-art performance optimization concepts. Module bundlers are built by brilliant people just to help you with these difficult tasks.

In addition, I recommend using a starter kit or a modern boilerplate project with webpack configuration best practices already in place. Building on this, you can make project-specific adjustments. I like this React + webpack 4 boilerplate project, which is also the basis of this blog’s accompanying demo project.

webpack 4 comes with appropriate presets. However, you have to understand a fair number of concepts to reap their performance benefits. Furthermore, the possibilities to tweak webpack’s configuration are endless, and you need extensive knowhow to do it the right way for your project.

You can follow along the examples with my demo project. Just switch to the mentioned branch so you can see for yourself the effects of the adjustments. The master branch represents the demo app, along with its initial webpack configuration. Just execute npm run dev to take a look at the project (the app opens on http://localhost:3000).

// package.json

"scripts": {

"dev": "webpack-dev-server --env.env=dev",

"build": "webpack --env.env=prod"

}

webpack 4 has introduced development and production modes. You should always ship a production build to your users. I want to emphasize this because you get a number of built-in optimizations automatically, such as tree shaking, performance hints, or minification with the TerserWebpackPlugin in production mode.

webpack 4 has adopted the software engineering paradigm convention over configuration, which basically means that you get a meaningful configuration simply by setting the mode to "production". However, you can tweak the configuration by overriding the default values. Throughout this article, we explain some of the performance-related configuration options that you can define as you wish for your project.

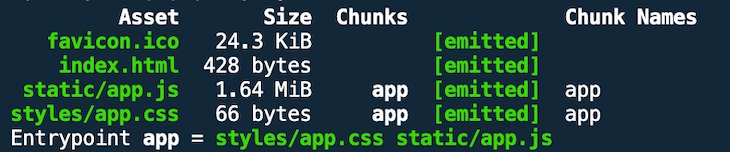

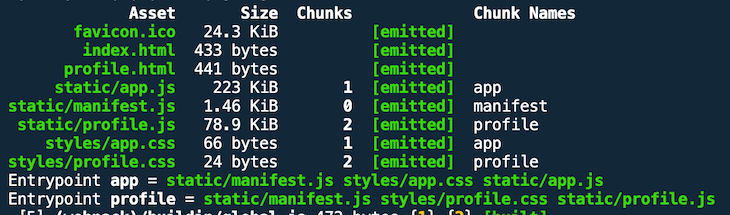

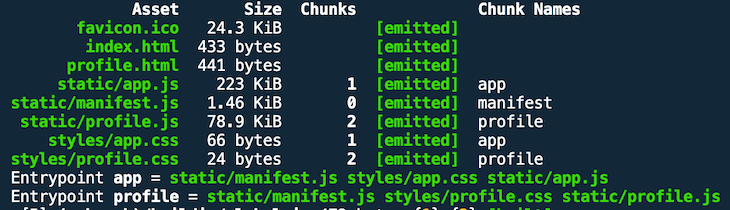

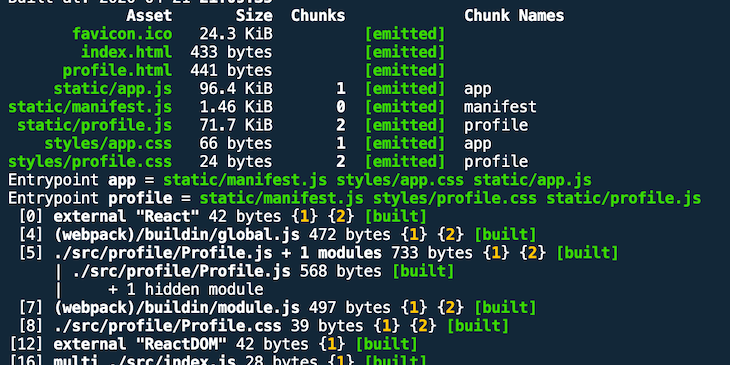

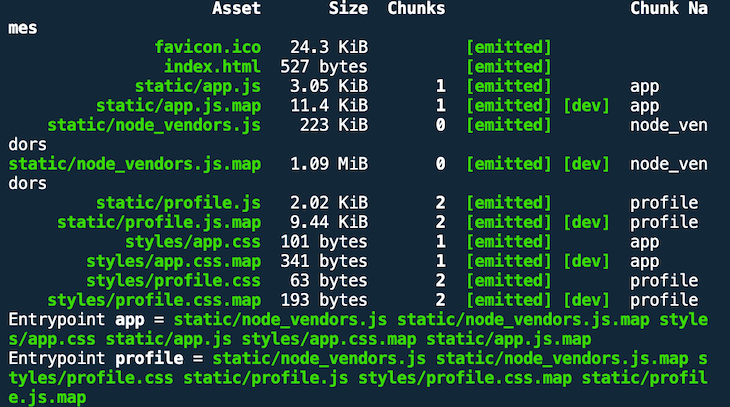

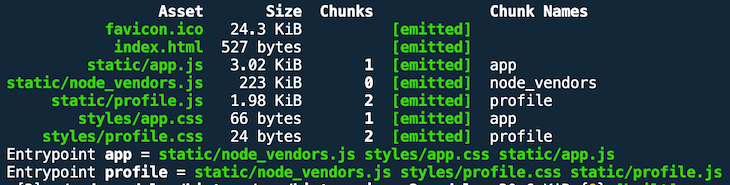

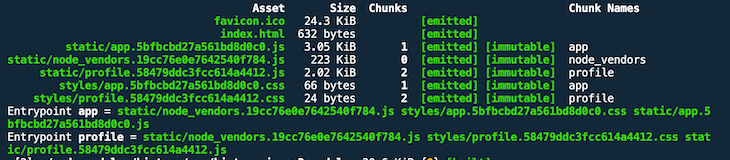

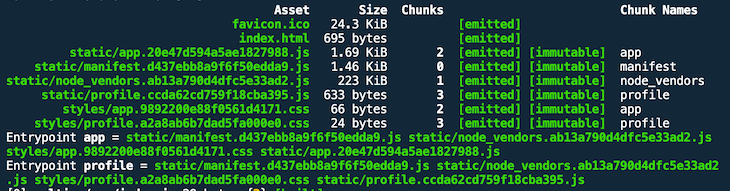

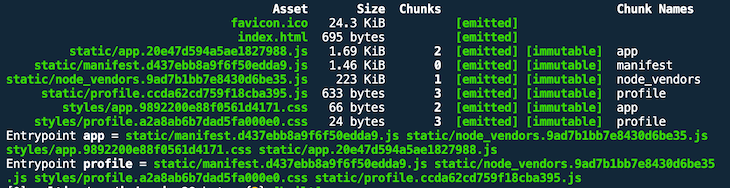

If you run npm run build (on the master branch), you get the following output:

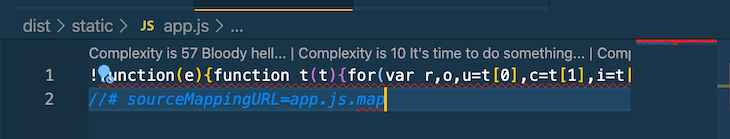

Open dist/static/app.js and you can see for yourself that webpack has uglified our bundle.

If you check out the branch use-production-mode, you can see how the app bundle size increases when you set the mode to "development" because some optimizations are not performed.

// webpack.prod.js

const config = {

+ mode: "development",

- mode: "production",

// ...

}

The result looks like this:

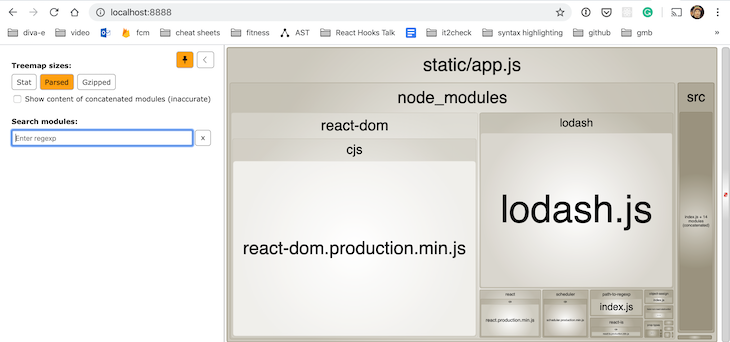

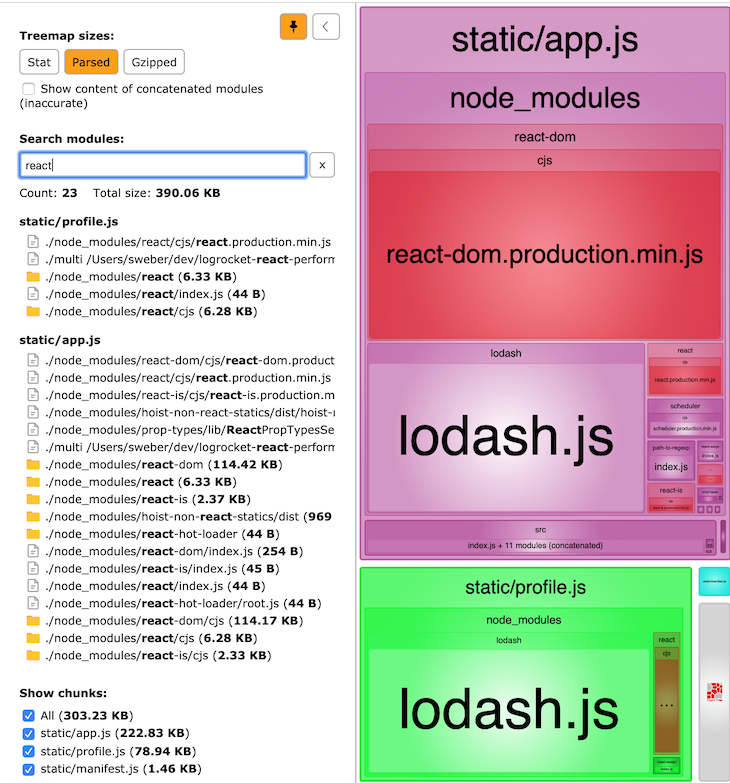

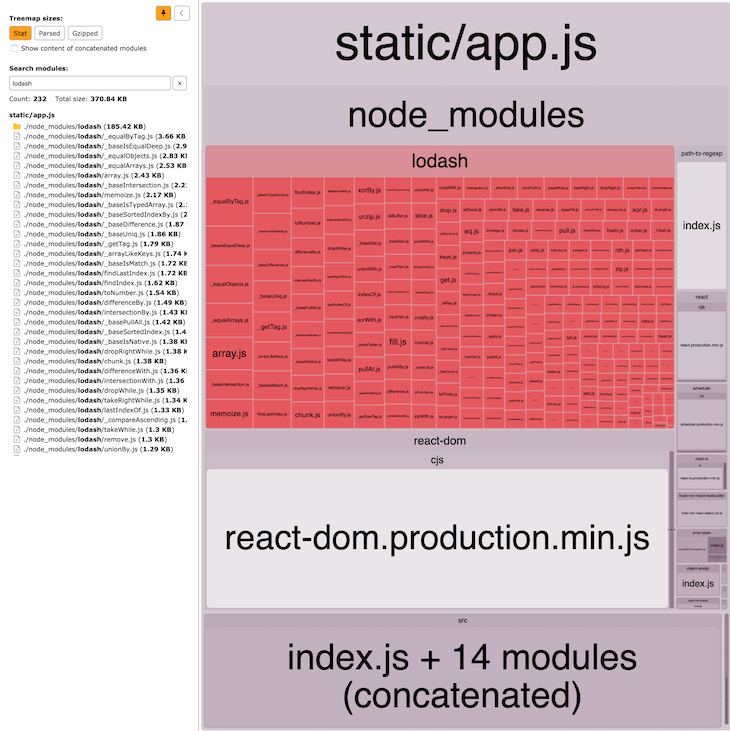

You should use the awesome webpack-bundle-analyzer plugin regularly to understand what your bundles consist of. In so doing, you realize what components really reside inside your bundles and find out which components and dependencies make up the bulk of their size — and you may discover modules that got there by mistake.

The following two npm scripts run a webpack build (development or production) and open up the bundle analyzer:

// package.json

"scripts": {

"dev:analyze": "npm run dev -- --env.addons=bundleanalyzer",

"build:analyze": "npm run build -- --env.addons=bundleanalyzer"

}

When you invoke npm run build:analyze, an interactive view opens on http://localhost:8888.

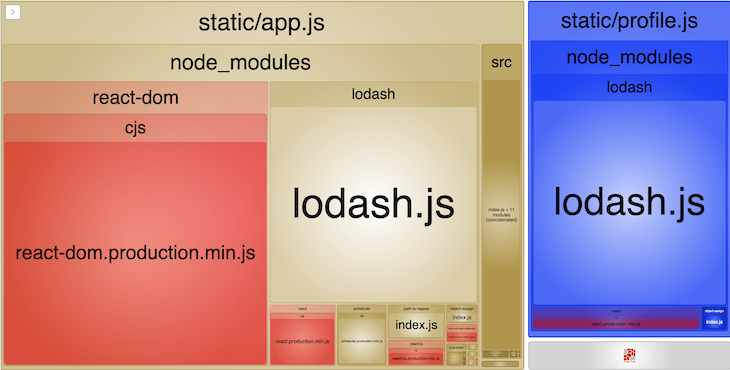

Our initial version of the demo project consists of only one bundle named app.js because we only defined a single entry point.

// webpack.prod.js

const config = {

mode: "production",

entry: {

app: [`${commonPaths.appEntry}/index.js`]

},

output: {

filename: "static/[name].js",

},

// ...

}

You should send the minified React production build to your users. Bundled React code is much smaller because it doesn’t include things that are really only useful during development time, like warnings.

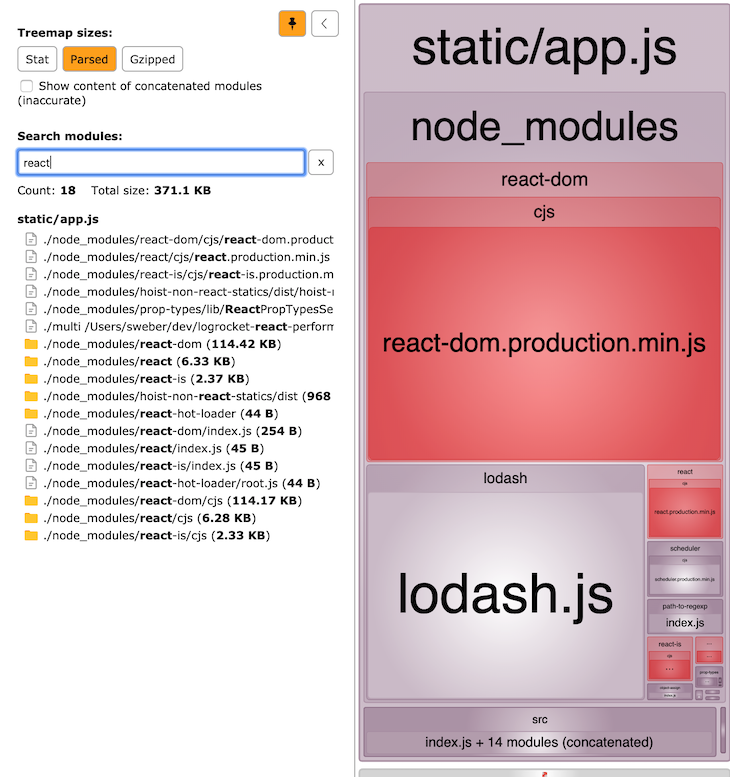

If you are using webpack in production mode, you come up with a React production build, as you can see in the last screenshot (react-dom.production.min.js).

The following screenshot shows a little bit more about the bundled React code.

If you take a closer look, you will see that there is still some code that does not belong in a production build (e.g., react-hot-loader). This is a good example of why frequent analysis of our generated bundles is an important part of finding opportunities for further optimization. In this case, the webpack/React setup needs improvement to exclude react-hot-loader.

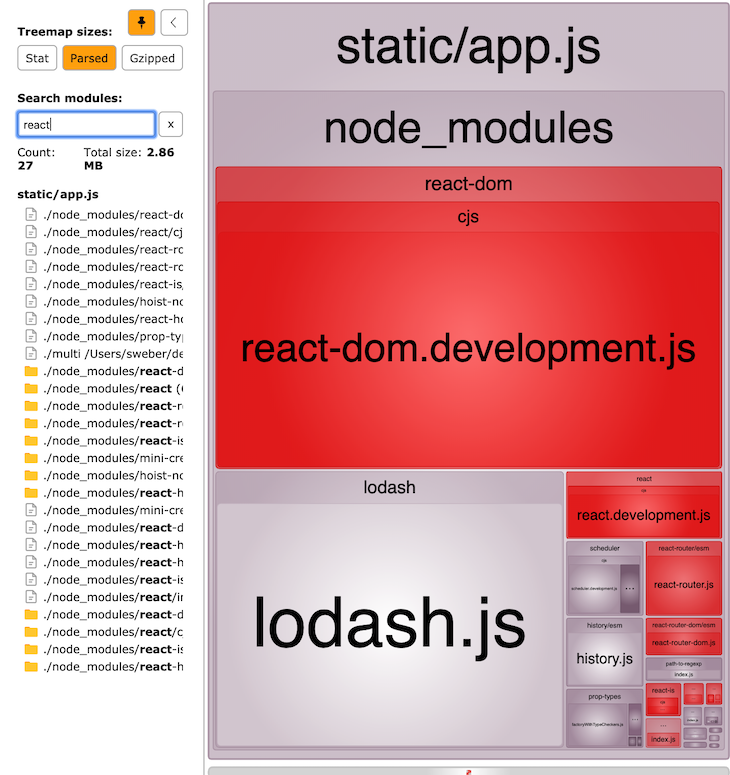

If you have an “insufficient production config” and set mode: "development", then you come up with a much larger React chunk (switch to branch use-production-mode and execute npm run build:analyze).

Instead of sending all our code in one large bundle to our users, our goal as frontend developers should be to serve as little code as possible. This is where code splitting comes into play.

Imagine that our user navigates directly to the profile page via the route /profile. We should serve only the code for this profile component. Here, we’ll add another entry point that leads to a new bundle (check out the entry-point-splitting branch).

// webpack.prod.js

const config = {

mode: "production",

entry: {

app: [`${commonPaths.appEntry}/index.js`],

+ profile: [`${commonPaths.appEntry}/profile/Profile.js`],

},

// ...

}

The consequence, of course, is that you have to make sure the bundles are included in one or more HTML pages depending on the project, whether a single-page application (SPA) or multi-page application (MPA). This demo project constitutes an SPA.

The good thing is that you can automate this composing step with the help of HtmlWebpackPlugin.

// webpack.prod.js

plugins: [

// ...

new HtmlWebpackPlugin({

template: `public/index.html`,

favicon: `public/favicon.ico`,

}),

],

Run the build, and the generated index.html consists of the correct link and script tags in the right order.

<!-- dist/index.html -->

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width,initial-scale=1" />

<meta http-equiv="X-UA-Compatible" content="ie=edge" />

<title>react performance demo</title>

<link rel="shortcut icon" href="favicon.ico" />

<link href="styles/app.css" rel="stylesheet" />

<link href="styles/profile.css" rel="stylesheet" />

</head>

<body>

<div id="root"></div>

<script src="static/app.js"></script>

<script src="static/profile.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

To demonstrate how to generate multiple HTML files (for an MPA use case), check out the branch entry-point-splitting-multiple-html. The following setup generates an index.html and a profile.html.

// webpack.prod.js

plugins: [

- new HtmlWebpackPlugin({

- template: `public/index.html`,

- favicon: `public/favicon.ico`,

- }),

+ new HtmlWebpackPlugin({

+ template: `public/index.html`,

+ favicon: `public/favicon.ico`,

+ chunks: ["profile"],

+ filename: `${commonPaths.outputPath}/profile.html`,

+ }),

+ new HtmlWebpackPlugin({

+ template: `public/index.html`,

+ favicon: `public/favicon.ico`,

+ chunks: ["app"],

+ }),

],

There are even more configuration options. For example, you can provide a custom chunk-sorting function with chunksSortMode, as demonstrated here.

webpack only includes the script for the profile bundle in the generated dist/profile.html file, along with a link to the corresponding profile.css. index.html looks similar and only includes the app bundle and app.css.

<!-- dist/profile.html -->

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width,initial-scale=1" />

<meta http-equiv="X-UA-Compatible" content="ie=edge" />

<title>react performance demo</title>

<link rel="shortcut icon" href="favicon.ico" />

<link href="styles/profile.css" rel="stylesheet" />

</head>

<body>

<div id="root"></div>

<script src="static/profile.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

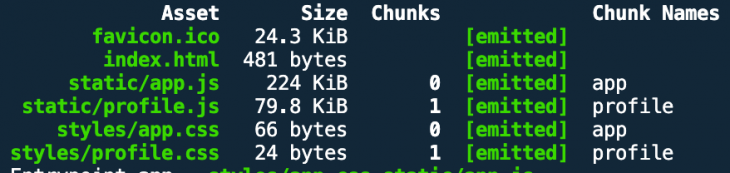

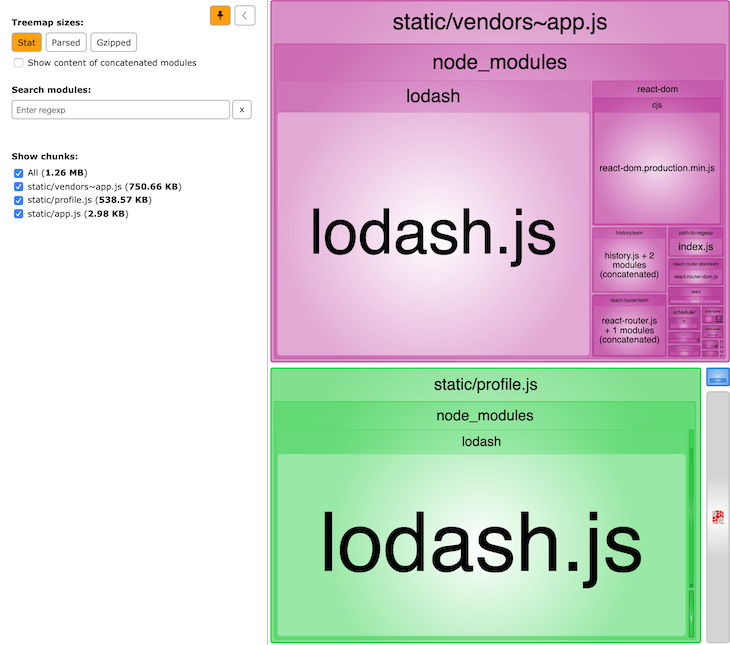

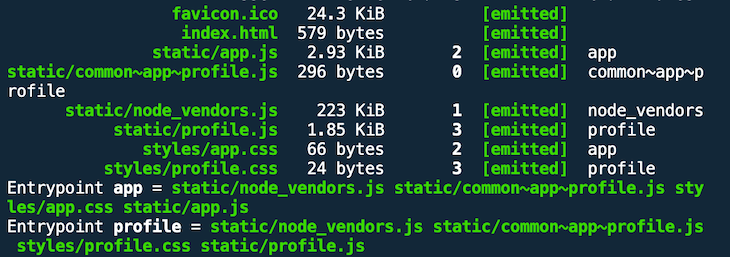

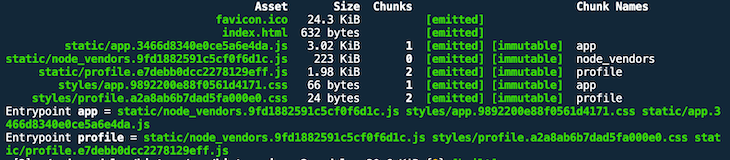

Check out the vendor-splitting branch. Let’s analyze the current state of our production build.

react.production.min.js and lodash.js are found redundantly in both bundles.

Is this a problem? Yes, because for any kind of app, you should separate the vendor chunks from your application chunks due to caching purposes. Your application code simply changes more often than the vendor code because you adjust versions of your dependencies less frequently.

Vendor bundles can thus be cached for a longer time, which benefits returning users. Vendor splitting means creating separate bundles for your application code and third-party libraries.

You can do this — and other code splitting techniques, as we will see in a minute — with the SplitChunksPlugin. Before we add vendor splitting, let’s take a look at the current production build output first.

In order to use the aforementioned SplitChunksPlugin, we add optimization.splitChunks to our config.

// webpack.prod.js

const config = {

// ...

+ optimization: {

+ splitChunks: {

+ chunks: "all",

+ },

+ },

}

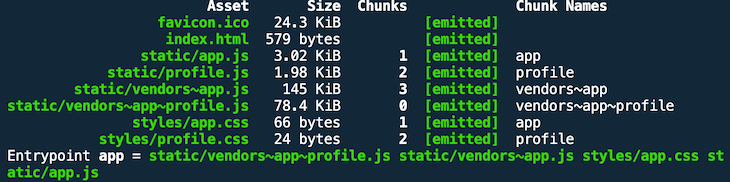

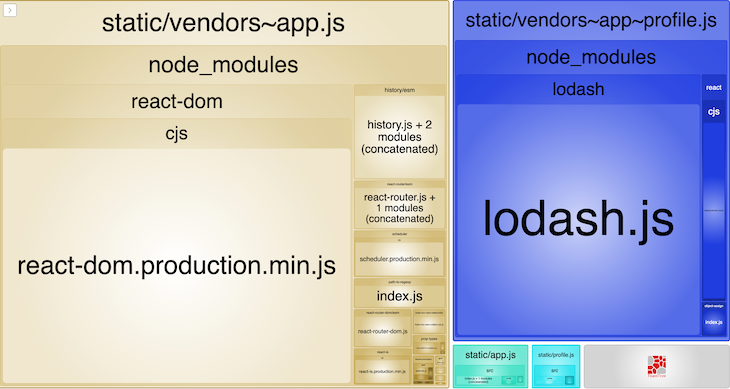

This time, we run the build with the bundle analyzer option (npm run build:analyze). The result of the build looks like this:

app.js and profile.js are much smaller now. But wait — two new bundles, vendors~app.js and vendors~app~profile.js, have come up. As you can see, with the bundle analyzer, we successfully extracted dependencies from node_modules (i.e., React, Lodash) into separate bundles. The tiny greenish boxes in the lower right are our app and profile bundles.

The names of the vendor bundles indicate from which application chunk the dependencies were pulled. Since React DOM is only used in the index.js file of the app.js bundle, it makes sense that the dependency is only inside of vendors~app.js. But why is Lodash in the vendors~app~profile.js bundle if it’s only used by the profile.js bundle?

Once again, this is webpack magic: conventions/default values, plus some clever things under the hood. I really recommend reading this article by webpack core member Tobias Koppers on the topic. The important takeaways are:

But the default behavior can be changed by the splitChunks options. We can set the minSize option to a value of 600KB and thereby tell webpack to first create a new vendor bundle if the dependencies it pulled out exceed this value (check out out the vendor-splitting-tweaking branch).

// webpack.prod.js

const config = {

// ...

optimization: {

splitChunks: {

chunks: "all",

+ minSize: 1000 * 600

},

},

}

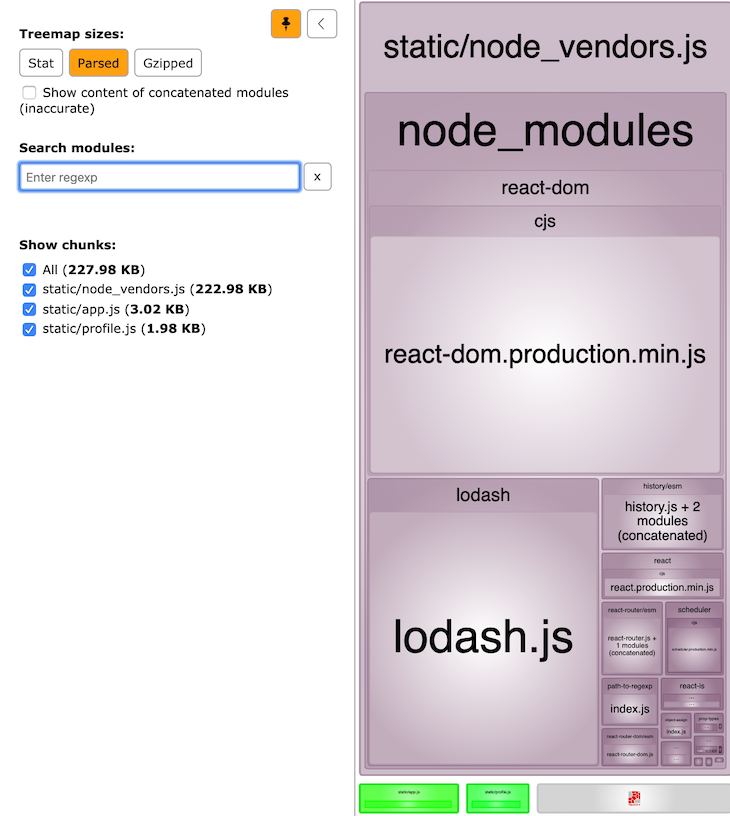

Now, webpack came up with only one vendor bundle, named vendors~app.js.

Why? If you check the Stat size, at 750KB, the new vendor bundle is larger than the minimum size of 600KB. webpack couldn’t create another chunk candidate for another vendor bundle because of our new configuration.

As you can see, Lodash is duplicated in the profile.js bundle, too (remember, webpack intentionally duplicates code). If you adjust the value of minSize to, e.g., 800KB, webpack cannot come up with a single vendor bundle for our demo project. I leave it up to you to try this out.

Of course, you could have more control if you wanted. Let’s assign a custom name: node_vendors. We define a cacheGroups property for our vendors, which we pull out of the node_modules folder with the test property (check out the vendor-splitting-cache-groups branch). In the previous example, the default values of splitChunks contains cacheGroups out of the box.

// webpack.prod.js

const config = {

// ...

- optimization: {

- splitChunks: {

- chunks: "all",

- minSize: 1000 * 600

- },

- },

+ optimization: {

+ splitChunks: {

+ cacheGroups: {

+ vendor: {

+ name: "node_vendors", // part of the bundle name and

+ // can be used in chunks array of HtmlWebpackPlugin

+ test: /[\\/]node_modules[\\/]/,

+ chunks: "all",

+ },

+ },

+ },

+ },

// ...

}

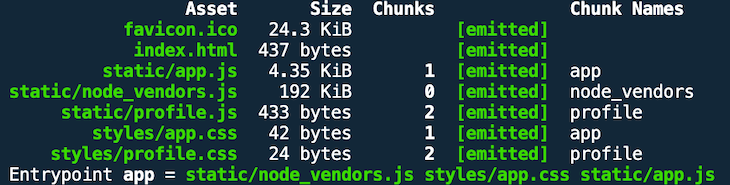

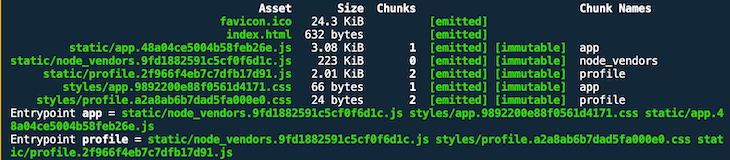

This time, webpack presents us with one vendor bundle with our custom name and all dependencies from node_modules combined in it.

In the splitChunks property above, we added a chunks property with a value of all. Most of the time, this value should be alright for your project. However, if you want to extract only lazy- or async-loaded bundles, you can use the value async. When we look at common code splitting in the next section, we’ll revisit this aspect.

Common code splitting aims to combine shared code into separate bundles to achieve smaller bundle sizes and more efficient caching. It’s similar to vendor code splitting, but the difference is that you target shared components and libraries within your own codebase.

In our example, we combine vendor code splitting with common code splitting (check out the branch common-splitting). We import and use the add function of util.js in the Blog and Profile components, which are part of two different entry points.

We add a new object with the key common to the cacheGroups object, with a regex to target only modules in our components folder. Since the components of this demo project are very tiny, we need to override webpack’s default value of minSize. We’ll set it to 0KB just in case.

// webpack.prod.js

const config = {

// ...

optimization: {

splitChunks: {

cacheGroups: {

vendor: {

name: "node_vendors", // part of the bundle name and

// can be used in chunks array of HtmlWebpackPlugin

test: /[\\/]node_modules[\\/]/,

chunks: "all",

},

+ common: {

+ test: /[\\/]src[\\/]components[\\/]/,

+ chunks: "all",

+ minSize: 0,

+ },

},

},

},

Running webpack generates a new bundle, common~app~profile.js, in addition to the two entry point bundles and our vendor bundle.

Search for console.log("add") within dist/static/common~app~profile.js and you’ll find what you’re looking for.

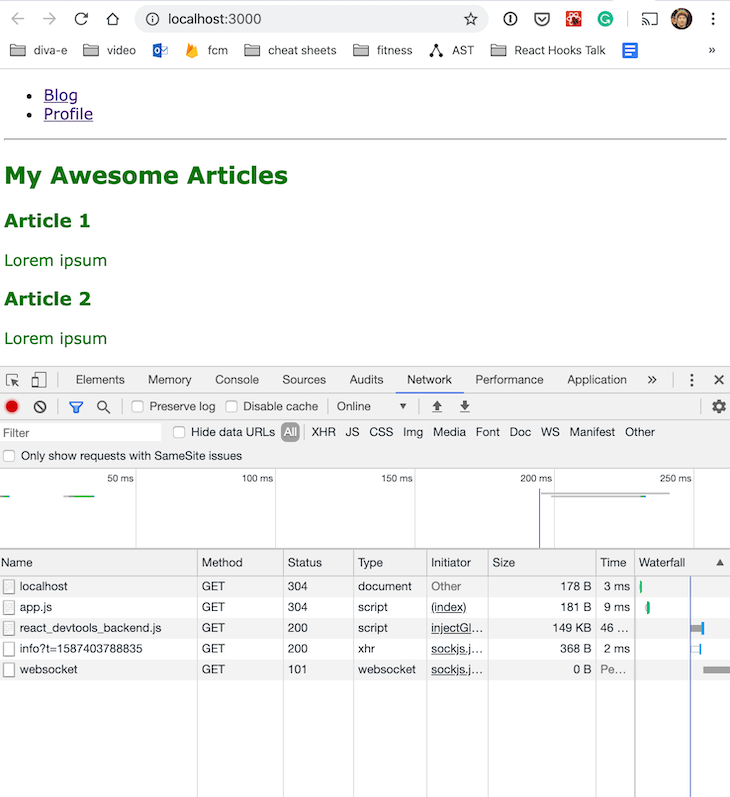

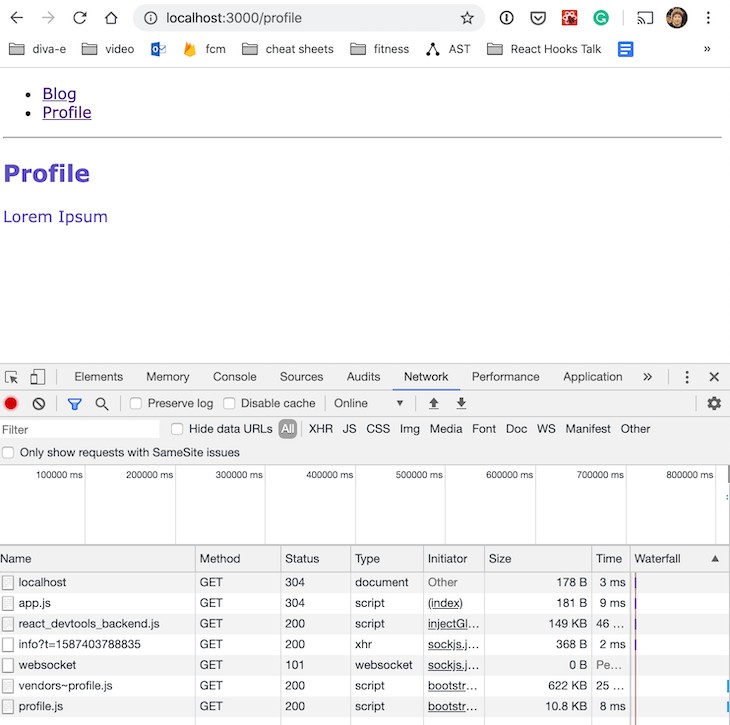

We’ve already seen how we can use react-router in combination with entry code splitting in the entry-point-splitting branch. We can push code splitting one step further by enabling our users to load different components on demand while they are navigating through our application. This use case is possible with dynamic imports and code splitting by route.

In the context of our demo project, this is evidenced by the fact that the profile.js bundle is only loaded when the user navigates to the corresponding route (switch to branch code-splitting-routes). We utilize the @loadable/components library, which does the hard work of code splitting and dynamic loading behind the scenes.

// package.json

{

// ...

"dependencies": {

"@loadable/component": "^5.12.0",

// ...

}

// ...

}

In order to use the ES6 dynamic import syntax, we have to use a babel plugin.

// .babelrc

{

// ...

"plugins": [

"@babel/plugin-syntax-dynamic-import",

// ...

]

}

The implementation is pretty straightforward. First, we need a tiny wrapper around our Profile component that we want to lazy-load.

// ProfileLazy.js import loadable from "@loadable/component"; export default loadable(() => import(/* webpackChunkName: "profile" */ "./Profile") );

We use the dynamic import inside the loadable callback and add a comment (to give our code-split chunk a custom name) that is understood by webpack.

In our Blog component, we just have to adjust the import for our Router component.

// Blog.js

import React from "react";

import { BrowserRouter as Router, Switch, Route, Link } from "react-router-dom";

- import Profile from "../profile/Profile";

+ import Profile from "../profile/ProfileLazy";

import "./Blog.css";

import Headline from "../components/Headline";

export default function Blog() {

return (

<Router>

<div>

<ul>

<li>

<Link to="/">Blog</Link>

</li>

<li>

<Link to="/profile">Profile</Link>

</li>

</ul>

<hr />

<Switch>

<Route exact path="/">

<Articles />

</Route>

<Route path="/profile">

<Profile />

</Route>

</Switch>

</div>

</Router>

);

}

// ...

The last step is to delete the profile entry point that we used for entry point code splitting from both the production and development webpack config.

// webpack.prod.js and webpack.dev.js

const config = {

// ...

entry: {

app: [`${commonPaths.appEntry}/index.js`],

- profile: [`${commonPaths.appEntry}/profile/Profile.js`],

},

// ...

}

Run a production build and you’ll see in the output that webpack created a profile.js bundle because of the dynamic import.

The generated HTML document does not contain a script pointing to the profile.js bundle.

// diest/index.html

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width,initial-scale=1" />

<meta http-equiv="X-UA-Compatible" content="ie=edge" />

<title>react performance demo</title>

<link rel="shortcut icon" href="favicon.ico" />

<link href="styles/app.css" rel="stylesheet" />

</head>

<body>

<div id="root"></div>

<script src="static/node_vendors.js"></script>

<script src="static/app.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

Wonderful — HtmlWebpackPlugin did the right job.

It’s easier to test this with the development build (npm run dev).

DevTools shows that the profile.js bundle is not loaded initially. When you navigate to the /profile route, though, the bundle gets loaded lazily.

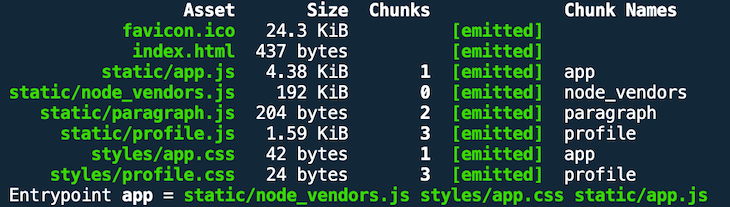

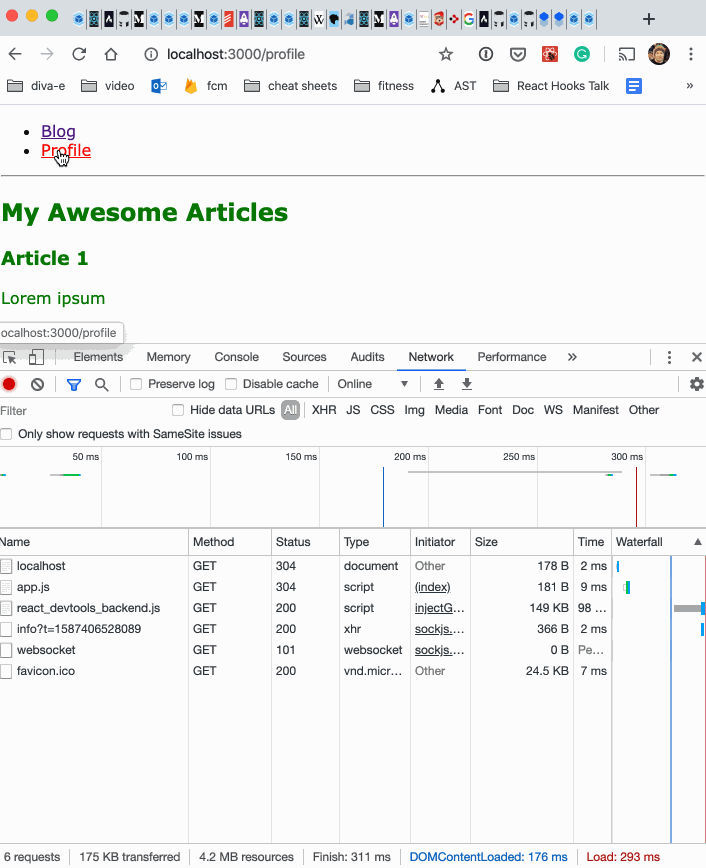

Code splitting is also possible on a fine-grained level. Check out branch code-splitting-component-level and you’ll see that the technique of route-based lazy loading can be used to load smaller components based on events.

In the demo project, we just add a button on the profile page to load and render a simple React component, Paragraph, on click.

// Profile.js

- import React from "react";

+ import React, { useState } from "react";

// some more boring imports

+ import LazyParagraph from "./LazyParagraph";

const Profile = () => {

+ const [showOnDemand, setShowOnDemand] = useState(false);

const array = [1, 2, 3];

_.fill(array, "a");

console.log(array);

console.log("add", add(2, 2));

return (

<div className="profile">

<Headline>Profile</Headline>

<p>Lorem Ipsum</p>

+ {showOnDemand && <LazyParagraph />}

+ <button onClick={() => setShowOnDemand(true)}>click me</button>

</div>

);

};

export default Profile;

ProfileLazy.js looks familiar. We want to call the new bundle paragraph.js.

// LazyParagraph.js import loadable from "@loadable/component"; export default loadable(() => import(/* webpackChunkName: "paragraph" */ "./Paragraph") );

I skip Paragraph because it is just a simple React component to render something on the screen.

The output of a production build looks like this.

The development build shows that loading and rendering the dummy component bundled into paragraph.js happens only on clicking the button.

What does this even mean? Every application or site built with webpack includes a runtime and manifest. It’s the boilerplate code that does the magic. The manifest wires together our code and the vendor code. It is not especially large, but it is duplicated for every entry point unless you do something about it.

Once again, if you want to optimize browser caching, then it might be useful to extract the manifest into a separate bundle. This saves your users from unnecessarily re-downloading files. However, I’m not sure how often the manifest changes — after webpack version updates?

Anyway, check out the branch manifest-splitting. The basis is our production configuration with two entry points and, now, vendor/common code splitting in place. In order to extract the manifest, we have to add the runtimeChunk property.

// webpack.prod.js

const config = {

mode: "production",

entry: {

app: [`${commonPaths.appEntry}/index.js`],

profile: [`${commonPaths.appEntry}/profile/Profile.js`],

},

output: {

filename: "static/[name].js",

},

+ optimization: {

+ runtimeChunk: {

+ name: "manifest",

+ },

+ },

// ...

}

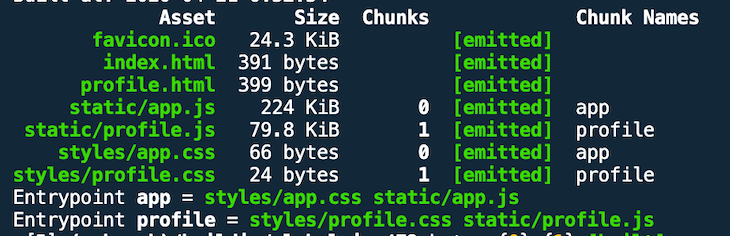

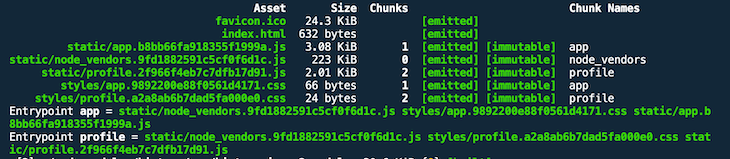

A production build shows a new manifest.js bundle. The two entry point bundles are a little bit smaller.

In contrast, here you can see the bundle sizes without the runtimeChunk optimization.

The two HTML documents were generated with an extra script tag for the manifest. As an example, here you can see the profile.html file (I skip index.html).

<!-- dist/profile.html -->

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width,initial-scale=1" />

<meta http-equiv="X-UA-Compatible" content="ie=edge" />

<title>react performance demo</title>

<link rel="shortcut icon" href="favicon.ico" />

<link href="styles/profile.css" rel="stylesheet" />

</head>

<body>

<div id="root"></div>

<script src="static/manifest.js"></script>

<script src="static/profile.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

With webpack’s externals config option, it is possible to exclude dependencies from bundling. This is useful if the environment provides the dependencies elsewhere.

As an example, if you work with different teams on a React-based MPA, you can provide React in a dedicated bundle that is included in the markup in front of each team’s bundles. This allows each team to keep this dependency out of its bundles.

This is the starting point (once again in branch manifest-splitting). We have two entry point bundles, both with React and one with the even bigger react-dom as dependencies.

If we want to exclude them from the production bundles, we have to add the following externals object to our production configuration (check out branch externals).

// webpack.prod.js

const config = {

// ...

+ externals: {

+ react: "React",

+ "react-dom": "ReactDOM",

+ },

// ...

}

When you create a production bundle, the file size is much smaller.

The size of app.js has shrunk from 223KB to 96.4KB because react-dom was left out. The file size of profile.js has decreased from 78.9KB to 71.7KB.

Now we have to provide React and react-dom in the context. In our example, we provide React over CDN by adding script tags to our HTML template files.

<!-- public/index.html -->

<body>

<div id="root"></div>

<script crossorigin

src="https://unpkg.com/react@16/umd/react.production.min.js"></script>

<script crossorigin

src="https://unpkg.com/react-dom@16/umd/react-dom.production.min.js"></script>

</body>

This is how the generated index.html looks (I’ll skip the profile.html file).

<!-- dist/index.html -->

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width,initial-scale=1" />

<meta http-equiv="X-UA-Compatible" content="ie=edge" />

<title>react performance demo</title>

<link rel="shortcut icon" href="favicon.ico" />

<link href="styles/app.css" rel="stylesheet" />

</head>

<body>

<div id="root"></div>

<script

crossorigin

src="https://unpkg.com/react@16/umd/react.production.min.js"

></script>

<script

crossorigin

src="https://unpkg.com/react-dom@16/umd/react-dom.production.min.js"

></script>

<script src="static/manifest.js"></script>

<script src="static/app.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

Imagine you have a component in your codebase with default and/or named exports that isn’t used anywhere in your application. It is a total waste to deliver this code in the JavaScript bundle to your users. Tree shaking is a dead code elimination technique that finds and strips that unused code from your bundles.

The good thing with webpack 4 is that you most likely don’t have to do anything to perform tree shaking. Unless you are working on a legacy project with the CommonJS module system, you get it automatically in webpack when you use production mode (you have to use ES6 module syntax, though).

Since you can use webpack without specifying a mode, or set it to "development", you have to meet a set of additional requirements, which is explained in great detail here. Also, as described in webpack’s tree shaking documentation, you have to make sure no compiler transforms the ES6 module syntax into the CommonJS version.

Since we use @babel/preset-env in our demo project, we better set modules: false to be on the safe side to disable transformation of ES6 module syntax to another module type.

// .babelrc

{

"presets": [

["@babel/preset-env", { "modules": false }],

"@babel/preset-react"

],

"plugins": [

// ...

]

}

This is because ES6 modules can be statically analyzed by webpack, which isn’t possible with other variants, such as require by CommonJS. It is possible to dynamically change exports and do all kinds of monkey patching. You can also see an example in this project where require statements are created dynamically within a loop:

// webpack.config.js

// ...

const addons = (/* string | string[] */ addonsArg) => {

// ...

return addons.map((addonName) =>

require(`./build-utils/addons/webpack.${addonName}.js`)

);

};

// ...

If you want to see how it looks without tree shaking, you can disable the UglifyjsWebpackPlugin, which is used by default in production mode.

Before we disable tree shaking, I first want to demonstrate that the production build indeed removes unused code. Switch to the master branch and take a look at the following file:

// util.js

export function add(a, b) { // imported and used in Profile.js

console.log("add");

return a + b;

}

export function subtract(a, b) { // nowhere used

console.log("subtract");

return a - b;

}

Only the first function is used within Profile.js. Execute npm run build again and open up dist/static/app.js. You can search and find two occurrences of the string console.log("add") but no occurrence of console.log("subtract"). This is the proof that it works.

Now switch to branch disable-uglify, where minimize: false is added to the configuration.

// webpack.prod.js

const config = {

mode: "production",

+ optimization: {

+ minimize: false, // disable uglify + tree shaking

+ },

entry: {

app: [`${commonPaths.appEntry}/index.js`],

},

// ...

}

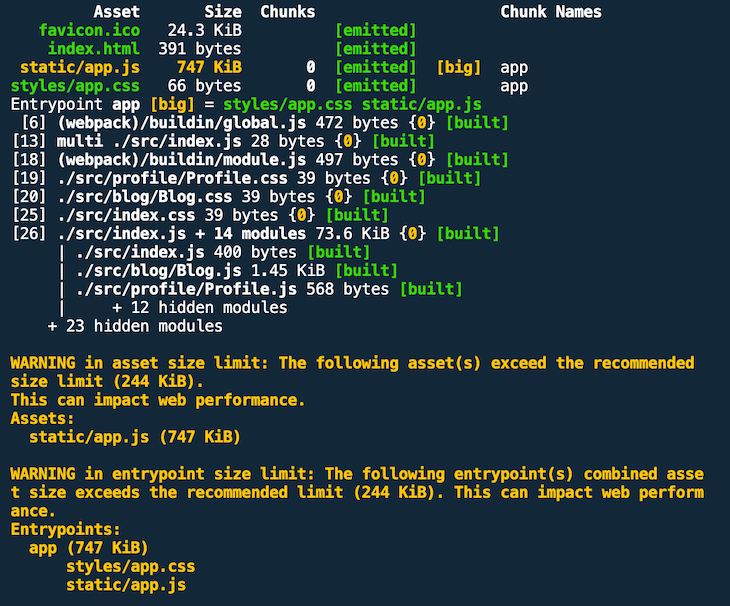

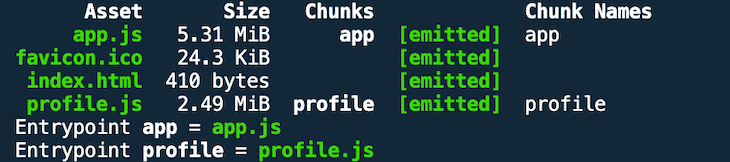

If you execute another production build, you get a warning that your bundle size exceeds the standard threshold.

In the non-defaced dist/static/app.js file, you also find two occurrences of console.log("subtract").

But why is the uglify plugin even involved? Well, the term tree shaking is a bit misleading: in this step, the dead leaves (e.g., unused functions) of the dependency graph are not removed. Instead, the uglify plugin does this in the second step. In the first step, a live code inclusion takes place to mark the source code in a way that the uglify plugin is able to “shake the syntax tree.”

It’s crucial to monitor the bundle sizes of your project. As the application grows over time, it’s important to understand when bundles grow too large and start impacting UX.

As you can see in the last screenshot, webpack has built-in support for performance measurement of assets. In the example above, we have colossally blown up the maximum threshold of 244KB with 747KB. In production mode, the default behavior is to warn you about threshold violations.

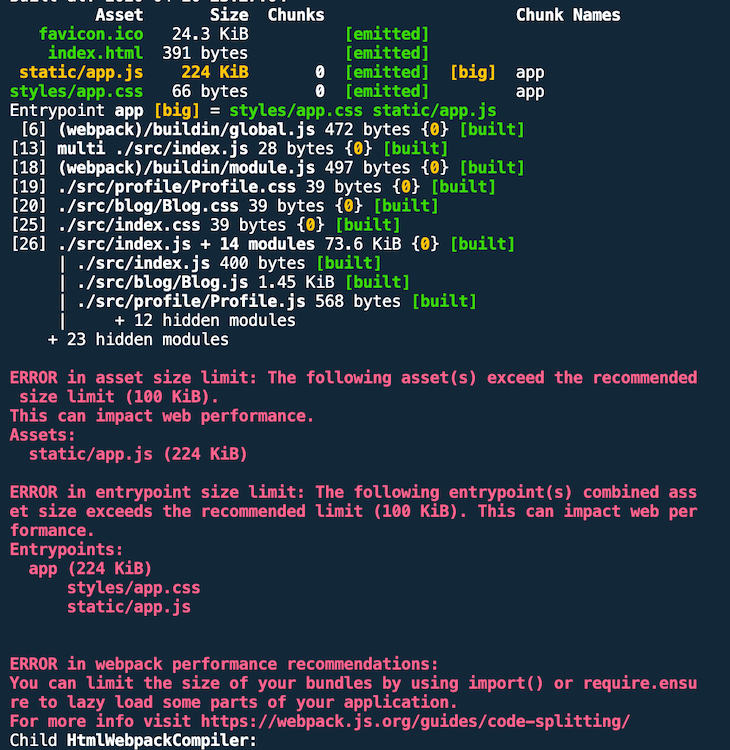

We can define our own performance budget for output assets. We don’t care for development, but we want to keep an eye on it for production (check out branch performance-budget).

// webpack.prod.js

const config = {

mode: "production",

entry: {

app: [`${commonPaths.appEntry}/index.js`],

},

output: {

filename: "static/[name].js",

},

+ performance: {

+ hints: "error",

+ maxAssetSize: 100 * 1024, // 100 KiB

+ maxEntrypointSize: 100 * 1024, // 100 KiB

+ },

// ...

}

We defined 100KB as a threshold for assets (e.g., CSS files) as well as entry points (i.e., generated JS bundles). In contrast to the previous screenshot (warning), here we define hints as type error.

As we see in our output, this means that the build will fail. With warning, however, the build will still succeed.

webpack offers advice on how to deal with the problems.

I like to set hints: "error" for the build. This causes your CI pipeline to fail if you push it to VCS anyway. In my opinion, this promotes a culture of caring about bundle/asset sizes and, ultimately, user experience early on.

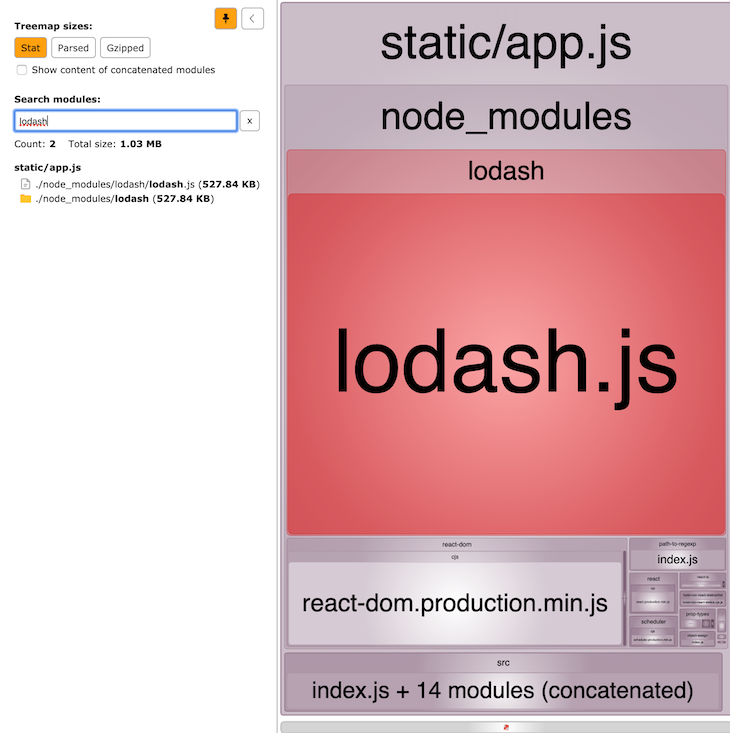

Let’s inspect our bundle to see how much space our popular Lodash dependency consumes in contrast to the other components. Check out out branch master and run npm run build:analyze.

That’s a pretty big chunk not only in absolute terms, but also in relation to the other components. This is how we use it.

// Profile.js

import _ from "lodash";

// ...

const Profile = () => {

const array = [1, 2, 3];

_.fill(array, "a");

console.log(array);

// ...

}

The problem is that we pull in the whole library even though we just use the fill function. Luckily, Lodash has a modular architecture and also supports tree shaking.

We just need to change the import to pull in only the array functions (check out branch lodash-modular).

// Profile.js - import _ from "lodash"; + import _ from "lodash/array"; // ...

The build output looks much better now.

The bottom line is that you should pay particular attention to your libraries when you inspect your bundles. If you use only a small portion of the total library scope, something is wrong. Check the library’s documentation to see whether you can import individual functionalities. Otherwise, look for modularized alternatives or roll your own solution.

We’ve now learned all but one of the requirements that must be met to have tree shaking in place, which is that external libraries need to tell webpack they don’t have side effects.

From webpack’s perspective, all libraries have side effects unless they tell it otherwise. Library owners have to mark their project, or parts of it, as side effect-free. Lodash also does this with the sideEffects: false property within its package.json.

It’s up to you and your team to decide if you want to ship source maps to production, whether for debugging reasons or to enable others to learn from you.

If you don’t want source maps at all for production bundles, you need to make sure no devtool configuration option is set for production mode. But if you do want to have source maps for production, take care that you use the right devtool variant because it has an effect on webpack’s build speed and, most importantly, on the size of the bundles.

For production, devtool: "source-map" is a good choice because only a comment is generated into the JS bundle. If your users do not open the browser’s devtools, they do not load the corresponding source map file generated by webpack.

For adding source maps, we just have to add one property to the production configuration (check out branch sourcemaps).

// webpack.prod.js

const config = {

mode: "production",

+ devtool: "source-map",

// ...

}

The following screenshot shows how the result would look for the production build.

webpack only added one line of comment in every asset.

In contrast, when you run the development build with devtool: "inline-source-map", you can clearly see why it’s not a good idea to use this configuration for production.

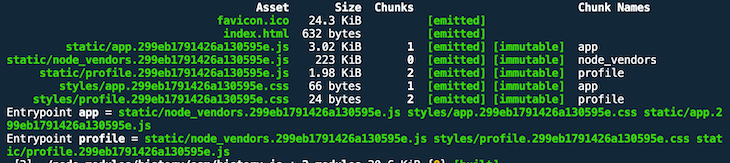

Check out the branch caching-no-optimization and run a production build to see the starting point.

Why is this result problematic? From a caching standpoint, the asset names are suboptimal. We should configure our web server to respond with Cache-Control headers that set appropriately large max-age values to support long-term browser caching.

With these filenames, however, we cannot invalidate browser-cached assets after webpack has generated new versions due to developer activity, like bug fixes, a new feature, etc. As a result, our users may end up using stale and buggy JavaScript bundles even though we already provided updated versions.

We can do better. We can use placeholder strings in different places in our webpack configuration — in the filename value, for example. We use [hash] to create a unique filename for an asset whenever we’ve made a change to the corresponding source files (check out branch caching-hash). We shouldn’t overlook our CSS assets, either.

// webpack.prod.js

const config = {

// ...

output: {

- filename: "static/[name].js",

+ filename: "static/[name].[hash].js",

},

// ...

plugins: [

new MiniCssExtractPlugin({

- filename: "styles/[name].css",

+ filename: "styles/[name].[hash].css",

}),

// ...

],

}

Cool, we have fancy hash values as part of our filenames. But not so fast — we’re not done yet. The result shows that all assets have the same hash value. This doesn’t help at all because whenever we change one file, all the other assets would receive the same hash value.

Let’s change Profile.js by adding a console.log statement and run the build again.

// Profile.js

const Profile = () => {

+ console.log("hello world");

// ...

};

export default Profile;

As expected, all assets get the same new hash value.

That’s because we have to use a different filename substitution placeholder. In addition to [name], we have three placeholder strings when it comes to caching:

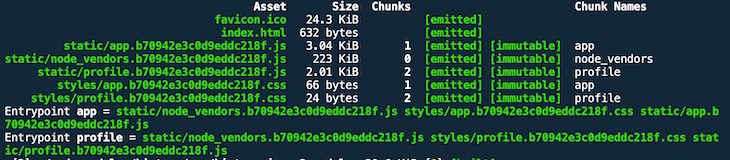

[hash] – if at least one chunk changes, a new hash value for the whole build is generated[chunkhash] – for every changing chunk, a new hash value is generated[contenthash] – for every changed asset, a new hash based on the asset’s content is generatedAt first, it’s not quite clear what the difference is between [chunkhash] and [contenthash]. Let’s try out [chunkhash] (check out branch caching-chunkhash).

// webpack.prod.js

const config = {

// ...

output: {

- filename: "static/[name].[hash].js",

+ filename: "static/[name].[chunkhash].js",

},

// ...

plugins: [

new MiniCssExtractPlugin({

- filename: "styles/[name].[hash].css",

+ filename: "styles/[name].[chunkhash].css",

}),

// ...

],

}

Give it a shot and run the production build again!

This looks a little better, but the hashes of the CSS assets match with their corresponding JS assets. Let’s change Profile.js and hope the corresponding CSS filename won’t be updated.

// Profile.js

const Profile = () => {

+ console.log("hello world again");

// ...

};

This result is even worse. As you can see in the screenshot below, not only does the Profile.css filename include the same new hash value as the new Profile.js, but both App.js and App.css were also updated with another new hash value.

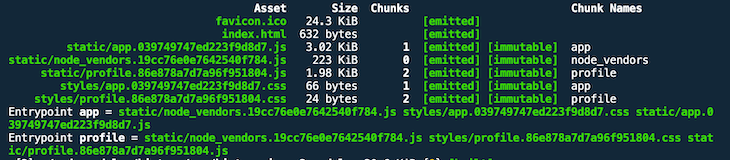

Maybe [contenthash] helps? Let’s find out (check out branch caching-contenthash).

// webpack.prod.js

const config = {

// ...

output: {

- filename: "static/[name].[chunkhash].js",

+ filename: "static/[name].[contenthash].js",

},

// ...

plugins: [

new MiniCssExtractPlugin({

- filename: "styles/[name].[chunkhash].css",

+ filename: "styles/[name].[contenthash].css",

}),

// ...

],

}

Each asset has been given a new but individual hash value.

Did we make it? Let’s change something in Profile.js again and find out.

// Profile.js

const Profile = () => {

+ console.log("Let's go");

// ...

};

CSS asset names have not changed, so we have decoupled them from the associated JS assets.

The vendor bundle still has the same name. Since the Profile React component is imported into the Blog React component, it’s OK that both filenames for both JS bundles have changed.

A change in Blog.js, though, should only lead to a change of the app bundle name and not of the profile bundle name because the latter imports nothing from the former.

// Blog.js

export default function Blog() {

+ console.log("What's up?");

// ...

}

This time, the profile bundle name is unchanged — great!

In addition, the official webpack docs recommend you also do the following:

moduleIdsCheck out branch caching-moduleids for the final version of our configuration.

// webpack.prod.js

const config = {

// ...

optimization: {

+ moduleIds: "hashed",

+ runtimeChunk: {

+ name: "manifest",

+ },

splitChunks: {

// ...

}

}

// ...

}

Now all the JS bundles have changed because the manifest was extracted out of them into a separate bundle. As a result, their sizes have shrunk a tiny bit.

I’m not sure when the manifest changes — maybe after a webpack version update? But we can verify the last step. If we update one of the vendor dependencies, the node_vendors bundle should get a new hash name, but the rest of the assets should remain unchanged. Let’s change a random dependency in package.json and run npm i && npm run build.

It was hard work, but it was worth it. Now we are better prepared for cache busting.

Performance optimization is a complicated matter, and webpack makes it a little less complicated.

The key to integrate performance optimization into your project is to understand some basic concepts, such as tree shaking, code splitting, and cache busting. Sure, webpack is an opinionated module bundler, but with a good understanding of the underlying principles, it is easier to work with the webpack documentation and achieve your desired performance goals.

This guide focuses mainly on performance optimization techniques regarding JavaScript. Some HTML was also included with the HtmlWebpackPlugin. There are more areas that could be covered, such as optimizing styles (e.g., CSS-in-JS, critical CSS) or assets (e.g., brotli compression), but that would be the subject of another article.

Would you be interested in joining LogRocket's developer community?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

This guide walks you through creating a web UI for an AI agent that browses, clicks, and extracts info from websites powered by Stagehand and Gemini.

This guide explores how to use Anthropic’s Claude 4 models, including Opus 4 and Sonnet 4, to build AI-powered applications.

Which AI frontend dev tool reigns supreme in July 2025? Check out our power rankings and use our interactive comparison tool to find out.

Learn how OpenAPI can automate API client generation to save time, reduce bugs, and streamline how your frontend app talks to backend APIs.

7 Replies to "An in-depth guide to performance optimization with webpack"

This was a fantastic read. Thank you very much. Unfortunately I was unable to get the separate entry points going when navigating directly to …/profile. Is this not intended to work like that?

Hi Daniel. Thanks for your kind words.

Have you tried out the branch dealing with entry point code splitting? https://github.com/doppelmutzi/react-performance-strategies/tree/entry-point-splitting

When you check it out, and execute “npm run dev:analyze” you should see that 2 bundles are created. Furthermore, when you go directly on the URL for the profile page (http://localhost:3000/profile), then it works for me. You can more about this topic in the section called “Add multiple entry points for bundle splitting”.

Does this help you?

Hi Sebastian,

Thank you for getting back to me and apologies for the confusion. I meant to refer to the entry-point-splitting-multiple-html branch. I do see the separated bundles and html files (index.html and profile.html) and navigating to index.html directly does work when running a dev server (because only one HtmlWebackPugin instance is defined in webpack.dev.js). However, when I build in prod mode and serve the dist folder using live-serer, the index.html file is served correctly (only loads app.js and displays the page), but when I navigate to profile.html (directly), the profile.html file is served correctly and when examining the network tab, only profile.js is loaded, however, the page remains blank. Incidentally, navigating via a link from the root works. I’ve tried adding sourcemaps to the prod build and debugging but haven’t gotten very far. Navigating to /profile returns a 404 (since there is no route associated with it I assume).

BTW you did help me shave off significant load times on https://staging.dle.dev compared to https://dle.dev. I’m not quite done optimizing yet, but I thought you’d appreciate seeing your (and Sean Larkin’s) recommendations implemented “in the wild”.

Hi Daniel,

don’t worry, I gladly answer your questions. Would you be so kind to explain what you would like to achieve in your project? If you ask because of your project https://staging.dle.dev/blog, then you obviously want to optimize a SPA.

You can use one single HtmlWebpackPlugin (first part in section “Add multiple entry points for bundle splitting”). Your question aims at an MPA approach. I just explained in the article how to generate multiple bundles (with multiple entry points) and how to automatically add them into different html files. However, how to serve these html files was not part of this article. I would recommend you to strive for the approach I explained in section “Lazy loading on the route level”. Then you still have one single bundle to include and when the user navigates to another

Furthermore, I have to admit that I have not made sure that every performance optimization step (i.e., every branch) leads to a runnable demo app for development and production mode. To be more precise, I had also not set myself the goal that the production build could be used in the demo app – I did not add an http-server and a workflow for this. As an example, when you open the production build (that uses react router) just from the file system, it does not work. My goal was mainly to have demo code and different versions of webpack configurations and discuss the output (bundle content, bundle sizes, etc.).

Feel free to reach out for me here or on Twitter to help you further.

Just awesome!

Just Awesome .. this is very in depth . It helped

Really nice article. Really a good amount of work is performed to write this article. Thanks!