Have you ever had to debug async operations in Node.js?

Why isn’t my callback being invoked? Why does my program hang? Which asynchronous operation is causing the problem? If you had to ask questions like this already, then you know how difficult it can be to diagnose and why we need all the help we can get.

We can get into a lot of strife working with async operations in JavaScript, but Node.js has a new tool that can help alleviate our pain. It’s called the async hooks API, and we can use it to understand what’s going on with the asynchronous operations in our application.

By itself, though, the Node.js API is quite low-level, and for any serious Node.js application, you’ll be overwhelmed by the sheer number of async operations that are in-flight, most of which you won’t care about! That’s not terribly useful to the average developer.

Unlike other blogs on this subject, this one won’t just regurgitate the Node.js docs at you. Instead, I’m going to show you a simple but very useful higher-level async debugging library that is built on top of the async hooks API.

You’ll learn some of the difficulties involved in creating a library like this and how to sidestep them. After this blog post, you should have an understanding of how to build your own async debugging library or, indeed, how to upgrade mine.

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

The example code for this blog post is available on GitHub.

I’ve tested this code on Node.js v12.6.0, but it should also work on any version from v8.17.0 onward. Results may vary on different versions of Node.js and different platforms. Please log an issue on GitHub if you find any problems.

To run the examples in this post, make a local clone of the example code repository and then run npm install:

git clone https://github.com/ashleydavis/debugging-async-operations-in-nodejs cd debugging-async-operations-in-nodejs npm install

I actually developed this code while working on Data-Forge Notebook, where a user can evaluate their notebook and have the code run in a separate, dedicated instance of Node.js.

The notebook editor displays a progress indicator during the evaluation, so it needs to know when the evaluation has finished. It’s only possible to know that by tracking how many asynchronous operations are in progress.

It took me many hours to figure out the intricacies and edge cases of tracking async operations in Node.js. I present here a simplified async debugging code library in the hope that it will help you to understand the async operations in your own application.

Let’s quickly get the basics out of the way. This is covered by a gazillion blog posts already, and it’s covered well enough in the Node.js docs.

Listing 1 below shows the simple code required to initialize the Node. js async hooks API so that we can start tracking asynchronous operations.

this.asyncHook = async_hooks.createHook({

init: (asyncId, type, triggerAsyncId, resource) => {

this.addAsyncOperation(asyncId, type, triggerAsyncId, resource);

},

destroy: asyncId => {

this.removeAsyncOperation(asyncId, "it was destroyed");

},

promiseResolve: asyncId => {

this.removeAsyncOperation(asyncId, "it was resolved");

},

});

this.asyncHook.enable();

In listing 1, we have a single init callback that is invoked whenever a new asynchronous operation has been created. We then add this asynchronous operation to our in-flight list.

We can also see that there are two ways for an operation to be wound up: either via destroy or promiseResolve. This caters to both traditional async operations and promises. At this point, we can remove the async operations from our in-flight list.

This is simple, is it not?

If it’s so simple to track asynchronous operations, then why do we need to go further than this? Let’s find out.

Unfortunately, the Node.js async hooks API is just too low-level. In a big application, we are likely to have numerous asynchronous operations in flight at any given time. Most of them won’t be a problem, and tracking all of them isn’t very helpful because finding a specific problem is like finding a needle in a haystack.

Instead, we should be able to track async operations created by restricted sections of code, then we can progressively reduce our problem domain to find those operations that are problematic.

That’s why I built the higher-level async debugger (you can find the code for it under the lib directory in the code repository). It allows us to focus our efforts so that we can intelligently narrow the problem domain and triangulate the source of the problem.

In addition, we’d like to understand the relationships between asynchronous operations so that we can follow the (probably long) chain from an async operation through its ancestors back to the originating line of code.

To effectively debug asynchronous operations in our application, we must face the following difficulties:

We’ll address these problems throughout this blog post. I’ve numbered them so that I can refer back to them.

Let me show you the simplest example of using the async debugger library. Listing 2 shows an example of tracking a simple timeout operation.

const { AsyncDebugger } = require("./lib/async-debugger.js");

function doTimeout() {

console.log("Starting timeout.");

setTimeout(() => {

console.log("Timeout finished.");

}, 2000);

}

const asyncDebugger = new AsyncDebugger();

asyncDebugger.notifyComplete(() => console.log("All done!"));

asyncDebugger.startTracking("test-1", doTimeout);

console.log("End of script");

In listing 2, we’d like to restrict tracking of asynchronous operations to the function doTimeout. This is a simple function that creates a timeout, but please try to imagine that, in a real scenario, there would be a complex chain of asynchronous operations initiated here.

The calls to notifyComplete and startTracking show the two main ways to configure the async debugger. With notifyComplete, we set a callback that will be invoked when all async operations have completed.

This only cares about the async operations that are actually being tracked, and in this example, that is only the async operations that are initiated within the doTimeout function. Any async operations initiated outside doTimeout will simply be ignored by the async debugger.

The function startTracking commences tracking of asynchronous operations. Here we pass in the doTimeout function. The async debugger invokes this function and uses the low-level API to track the async operations that it initiates.

You should run the code in example-1.js to see what happens:

node example-1.js

You’ll see that five low-level async operations are created to support our timeout:

%% add 4, type = TTYWRAP, parent = 3, context = 3, test-1 #ops = 1, total #ops = 1 %% add 5, type = SIGNALWRAP, parent = 3, context = 3, test-1 #ops = 2, total #ops = 2 Starting timeout. %% add 6, type = TickObject, parent = 3, context = 3, test-1 #ops = 3, total #ops = 3 %% add 7, type = Timeout, parent = 3, context = 3, test-1 #ops = 4, total #ops = 4 End of script %% remove 6, reason = it was destroyed, context = 3, test-1 #ops = 3, total #ops = 3 Timeout finished. %% add 1082, type = TickObject, parent = 7, context = 3, test-1 #ops = 4, total #ops = 4 %% remove 7, reason = it was destroyed, context = 3, test-1 #ops = 3, total #ops = 3 %% remove 1082, reason = it was destroyed, context = 3, test-1 #ops = 2, total #ops = 2

The first question you might ask is, why do we have so many async operations for a timeout? The timeout by itself only requires a single async operation; the other operations are generated by console.log which happens to be asynchronous (difficulty no. 1).

The real problem here is that our application has hung. This isn’t really a problem with the code we are debugging (there’s nothing wrong with it); instead, it’s a problem with how we track global asynchronous operations (difficulty no. 2).

My first thought was that we need to force garbage collection and clean up the remaining asynchronous operations. That can be an issue, but it’s not the case here, and I’ll come back to the garbage collection issue again later.

We can see a solution to this problem in example-2.js. This is the same as example-1.js, but with the addition of a call to console.log before we initiate tracking. Amazingly, this makes the code work as expected! Run it now to see what happens:

node example-2.js

You’ll see now that our notifyComplete callback is invoked, and the program exits normally. Why is that?

By putting a console.log outside the code, we are forcing the global standard output channel to be created outside the scope of the async debugger. It therefore doesn’t know about it and doesn’t care. Since all the async operations that the debugger knows about do get resolved, it stops checking, and our program is thus allowed to exit.

It is rather annoying that we must change our code in order to get our debugger to work, but I haven’t found another way to deal with this rather awkward situation.

Now that we know the basics of using the async debugger library, let’s use it to trace the source of a more complex asynchronous operation.

In listing 3, you can see an example of a nested timeout.

function doTimeout() {

console.log("Starting timeout.");

setTimeout(() => {

setTimeout(() => {

console.log("Timeout finished.");

}, 2000);

}, 2000);

}

We’d like to track the nested timeout in listing 3 back to the code where it originated. Obviously, in this simple example, we can see that directly in the code we are looking at. That’s because the code is co-located and easy to read.

Imagine, though, a more complex situation in which there are links in the asynchronous chain from separate code files. In that case, it’s not so easy to trace the chain of asynchronous operations.

Run example-3.js to see the output it generates:

Starting up! Starting timeout. %% add 7, type = TickObject, parent = 6, context = 6, test-1 #ops = 1, total #ops = 1 %% add 8, type = Timeout, parent = 6, context = 6, test-1 #ops = 2, total #ops = 2 End of script %% remove 7, reason = it was destroyed, context = 6, test-1 #ops = 1, total #ops = 1 %% add 1163, type = Timeout, parent = 8, context = 6, test-1 #ops = 2, total #ops = 2 %% remove 8, reason = it was destroyed, context = 6, test-1 #ops = 1, total #ops = 1 Timeout finished. %% add 2323, type = TickObject, parent = 1163, context = 6, test-1 #ops = 2, total #ops = 2 %% remove 1163, reason = it was destroyed, context = 6, test-1 #ops = 1, total #ops = 1 %% remove 2323, reason = it was destroyed, context = 6, test-1 #ops = 0, total #ops = 0

You can see in the output above how the inner timeout (operation 1163) relates back to the outer timeout (operation 8).

The Node.js async hooks API does not make it easy for you to relate chains of asynchronous operations (difficulty no. 3). However, my async debugging library will make these connections for you.

In listing 4, I show how to debug our code that is running under label test-1 (our nested timeout). This prints the tree/chain of asynchronous operations and the lines of code where they originated.

asyncDebugger.notifyComplete(() => {

asyncDebugger.debug("test-1");

});

The output from this shows you the tree of async operations, their type, their status, and the originating callstack:

|- 7 - TickObject - completed | at AsyncDebugger.addAsyncOperation (async-debugger.js:216:15) | at AsyncHook.init (async-debugger.js:163:26) | at emitInitNative (internal/async_hooks.js:134:43) | at emitInitScript (internal/async_hooks.js:341:3) | at new TickObject (internal/process/task_queues.js:102:7) | at process.nextTick (internal/process/task_queues.js:130:14) | at onwrite (_stream_writable.js:472:15) | at afterWriteDispatched (internal/stream_base_commons.js:149:5) | at writeGeneric (internal/stream_base_commons.js:137:3) | at WriteStream.Socket._writeGeneric (net.js:698:11) |- 8 - Timeout - completed | at AsyncDebugger.addAsyncOperation (async-debugger.js:216:15) | at AsyncHook.init (async-debugger.js:163:26) | at emitInitNative (internal/async_hooks.js:134:43) | at emitInitScript (internal/async_hooks.js:341:3) | at initAsyncResource (internal/timers.js:147:5) | at new Timeout (internal/timers.js:178:3) | at setTimeout (timers.js:142:19) | at doTimeout (example-4.js:14:5) | at async-debugger.js:76:13 | at AsyncResource.runInAsyncScope (async_hooks.js:172:16) | |- 1164 - Timeout - completed | | at AsyncDebugger.addAsyncOperation (async-debugger.js:216:15) | | at AsyncHook.init (async-debugger.js:163:26) | | at emitInitNative (internal/async_hooks.js:134:43) | | at emitInitScript (internal/async_hooks.js:341:3) | | at initAsyncResource (internal/timers.js:147:5) | | at new Timeout (internal/timers.js:178:3) | | at setTimeout (timers.js:142:19) | | at Timeout._onTimeout (example-4.js:16:9) | | at listOnTimeout (internal/timers.js:531:17) | | at processTimers (internal/timers.js:475:7) | | |- 2288 - TickObject - completed | | | at AsyncDebugger.addAsyncOperation (async-debugger.js:216:15) | | | at AsyncHook.init (async-debugger.js:163:26) | | | at emitInitNative (internal/async_hooks.js:134:43) | | | at emitInitScript (internal/async_hooks.js:341:3) | | | at new TickObject (internal/process/task_queues.js:102:7) | | | at process.nextTick (internal/process/task_queues.js:130:14) | | | at onwrite (_stream_writable.js:472:15) | | | at afterWriteDispatched (internal/stream_base_commons.js:149:5) | | | at writeGeneric (internal/stream_base_commons.js:137:3) | | | at WriteStream.Socket._writeGeneric (net.js:698:11)

So how does the async debugger connect the relationships between asynchronous operations? Internally, it builds a tree data structure that manages the relationship and connects child and parent async operations.

Whenever the Node.js async hooks API notifies of a new asynchronous operation, it also gives us the ID of the parent. We can use this to look up our record for the parent and then add the new operation as a child. We can thus build out a tree data structure that represents the family of asynchronous operations.

If the parent is not found in our records, we can instead record the new operation as a new root in the tree (so actually we can have multiple trees, depending on how many segments of code we are tracking).

So the async debugger can link related async operations in a tree. We can traverse the tree to find the callstack that originated the async operation. For this, we must generate a callstack and record it against the async operation. Fortunately, JavaScript makes it very easy to capture the current callstack, as shown in listing 5.

const error = {};

Error.captureStackTrace(error);

const stack = error.stack.split("\n").map(line => line.trim());

There’s no point monitoring all async operations in your application. That’s just going to make things really confusing. There’ll be way too much noise and too little signal. To find the source of a problem we need to progressively restrict the space in which it can hide until it has nowhere left to hide.

The async debugger achieves this with the startTracking function. The Node.js async hooks API, when enabled, is a blunt tool. It notifies us of each and every new asynchronous operation in our application — even those that we aren’t interested in. The trick here is to know which async operations are relevant so that we can focus on those.

We can achieve this by forcing all the operations we wish to debug to be nested under a known parent operation. When we know the ID of the parent operation, we can use our tree data structure to make the connection between the parent and any descendent operations. We can therefore know whether any given async operation is relevant and should be tracked.

But how do we generate a parent operation? We will use the AsyncResource class to synthesize an artificial asynchronous operation. We can then capture the async ID of our parent operation and use that to identify the child operations that are to be tracked.

Listing 6 shows how this is implemented in the async debugger. The async hooks function executionAsyncId is used to retrieve the async ID of the synthesized asynchronous operation. We then run the user code in the context of the parent operation. Any asynchronous operations generated by the child will automatically be linked to the parent now.

const executionContext = new async_hooks.AsyncResource(label);

executionContext.runInAsyncScope(() => {

const executionContextAsyncId = async_hooks.executionAsyncId();

// ... code omitted here …

userCode(); // Run the user

});

There is one more problem we should address, but unfortunately, I haven’t been able to replicate it in a simple code example. In more complex situations, I found that the intermittent nature of the Node.js garbage collector records some asynchronous operations as alive for longer than they actually are.

This is clearly just an issue in how the Node.js async hooks API reports removal of asynchronous operations. It’s not actually a production issue, but it does sometimes make things confusing when trying to debug asynchronous operations.

We can solve this by periodically forcing garbage collection. As you can see in listing 7, this is achieved with the function global.gc.

if (global.gc) {

global.gc();

}

The call to global.gc is wrapped in an if statement. Normally, the gc function isn’t available, and the if statement allows the async debugger to run under normal conditions. To expose the gc function, we need to use the Node.js command line argument --expose-gc.

Try running it yourself like this:

node --expose-gc example-2.js

Like I said, I couldn’t find a simple way to demonstrate this. But if you are debugging a more complex situation, you might find that you have outstanding asynchronous operations that can be cleaned up by forcing garbage collection.

If you are coding your own async debugging library (or otherwise making upgrades to mine), you’ll most certainly need to debug your debugging code at some point. The easiest way to do this is by using console logging, but unfortunately, we can’t simply use console.log.

This function itself is asynchronous (difficulty no. 1), and we should not invoke any new asynchronous operations from our debugging code. This would cause more asynchronous operations and can result in more confusion.

If you peruse the debugger code, you’ll find multiple places where I use fs.writeSync (here, for example) to generate debug output. Listing 8 shows you an example.

fs.writeSync(1, `total #ops: ${this.getNumAsyncOps()}\n`);

writeSync allows us to write synchronously to a file. Note that we are writing to file descriptor 1. This refers to the standard output channel, so it’s pretty much the same as using console.log, but it’s just not asynchronous.

In this blog post, you have learned how to use my async debugging library to debug asynchronous operations in Node.js. In the process, we worked through some of the difficulties you must address to do this kind of async debugging.

You are now in a good position to debug your own asynchronous code, build your own debugging library, or make upgrades to my debugging library.

Good luck nailing your asynchronous problems!

Monitor failed and slow network requests in production

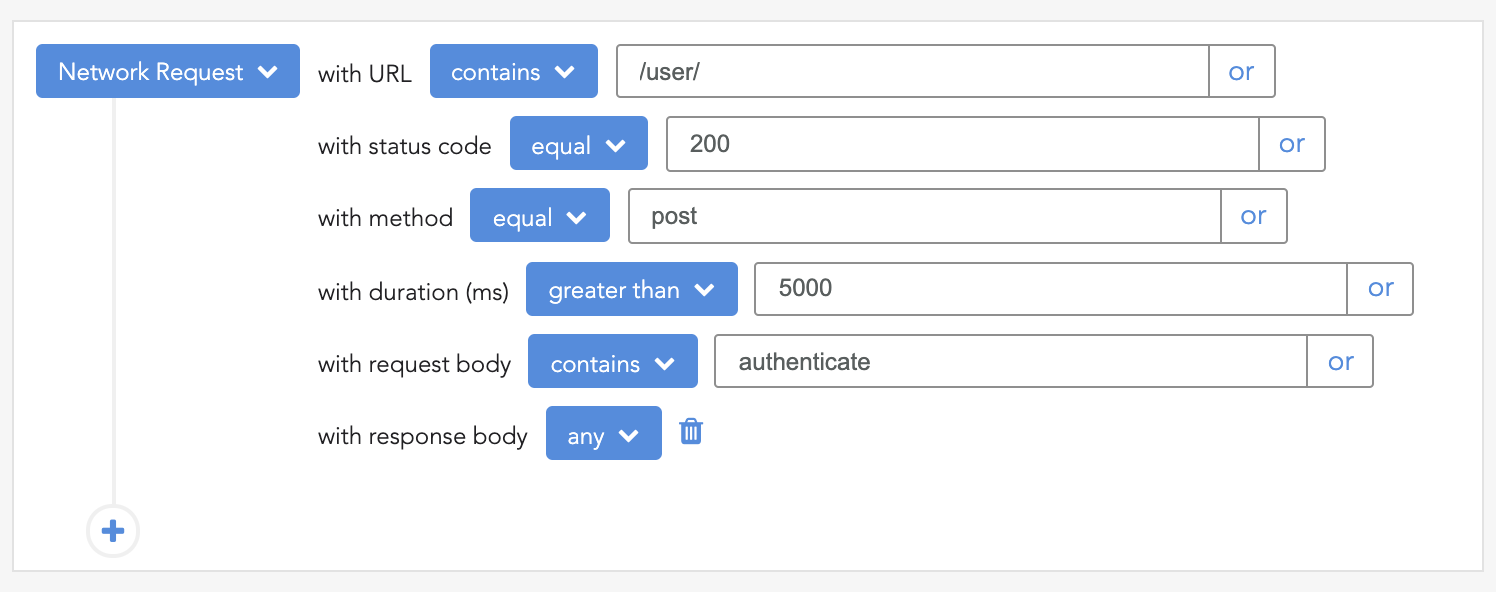

Monitor failed and slow network requests in productionDeploying a Node-based web app or website is the easy part. Making sure your Node instance continues to serve resources to your app is where things get tougher. If you’re interested in ensuring requests to the backend or third-party services are successful, try LogRocket.

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork around why bugs happen by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings — compatible with all frameworks.

LogRocket's Galileo AI watches sessions for you, instantly identifying and explaining user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

LogRocket instruments your app to record baseline performance timings such as page load time, time to first byte, slow network requests, and also logs Redux, NgRx, and Vuex actions/state. Start monitoring for free.

Solve coordination problems in Islands architecture using event-driven patterns instead of localStorage polling.

Signal Forms in Angular 21 replace FormGroup pain and ControlValueAccessor complexity with a cleaner, reactive model built on signals.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the February 25th issue.

Explore how the Universal Commerce Protocol (UCP) allows AI agents to connect with merchants, handle checkout sessions, and securely process payments in real-world e-commerce flows.

Would you be interested in joining LogRocket's developer community?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now