Manually restarting an application’s process after each change to the codebase can be both exhausting and frustrating. Fortunately, one brilliant developer eventually said “enough!” and decided to put an end to the madness with a very simple package — Nodemon.

Nodemon watches for any changes occurring inside a given directory and restarts our app after each one, letting us focus solely on writing the code. Using something like Nodemon is a great way to deepen our understanding of how a file system works and to further our appreciation of the Node.js environment in general.

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

When I first came across Nodemon, I couldn’t help but wonder how it’s possible to get notifications about changes in the file system.

While these are all fair guesses, Nodemon works somewhat differently.

If we check the Node.js documentation, we see that there is an API for watching files. It is called FSWatcher (FileSystemWatcher), and it lets us set up a callback to be executed once a directory or a file is changed.

Before we start celebrating all the possibilities this presents, let’s look at a problem that makes working with this API troublesome. You see, changing a file can sometimes notify us twice. This is quite a nuisance, as it happens because of the way most operating systems are designed*. This, in turn, means we cannot treat it like a regular bug in Node.js and fix it by simply sending a pull request.

*For example, Windows Notepad performs multiple file system actions during the writing process. Notepad writes to the disk in batches that create the content of the file and then the file attributes. Other applications may work in a similar manner. Because FileSystemWatcher monitors the operating system activities, all events that these applications fire will be picked up on.

To prevent the repeated notifications, as well as some other known bugs, we are going to use a package called chokidar. With all the improvements and fixes that this package provides for watching a file system, we can finally start considering other libraries that we are going to use in our application.

I have chosen RxJS as the core library because it makes working with event-based architecture easy to manage. Thanks to the observables and their streams, we will no longer find ourselves in callback hell, calling function after function inside our event handler.

Working with RxJS revolves around what we call reactive programming, the whole idea of which is based on operations made on a stream created by an observable. You can think of an observable as being a kind of promise that can return multiple values. Each time an event occurs, a new value is passed to our stream, resulting in every function inside the pipe method being called with that value as an argument.

It may feel strange at first to write code in adherence to the reactive programming paradigm, as even the simplest tasks may seem overly complicated. But after a while, it will become just another way of programming — and a fun one at that, too.

If you have ever come in contact with Angular‘s HTTP client (which uses RxJS), all this is going to seem familiar. Otherwise, if you have not tried Angular yet, it might be a good idea to get a thorough grasp on the fundamentals of RxJS now, as it will make learning Angular much quicker in the future.

To get a firm understanding of basics of RxJS, I recommend reading:

http://reactivex.io/rxjs/manual/overview.html

https://rxjs-dev.firebaseapp.com/guide/overview

We would like our app to be accessible like a command in our console, as is the original Nodemon:

npm run start -- -e ts,js,html -w src -i build -d 5000 -x "ls -l"

Of course, later — after releasing our package — npm run start is going to be replaced by the name of our package, for example our-nodemon.

We are going to throw in some colors just for fun.

Go ahead, copy the repository and let’s get started.

Every time we execute a script we can pass arguments to it. All arguments that are passed to our process can be found in the variable called process.argv.

So now, before we move on to see the actual implementation, let’s consider what it is exactly that we would like the user to pass to our app. Here are a few arguments I have in mind:

Note that only the –exe argument is required since every other option can be set to default.

We can parse arguments in many ways, but the easiest one is to use a commander. A commander parses the arguments and gives us the ability to declare them in a very neat way, just like we did in the list above:

const commandArguments = program

.version('1.0.0')

.option('-e, --ext <items>', 'Extensions to watch', parsers.list)

.option('-w, --watch <items>', 'Directories to watch', parsers.list)

.option('-i, --ignore <items>', 'Directories to ignore', parsers.list)

.option('-d, --delay <n>', 'Delay before the execution', parsers.int)

.option('-x, --exe <script>', 'Execute script on restart')

.parse(process.argv)

Here we can see some methods of the parsers object. A commander needs them in order to change an argument passed as a string to the format we expect:

const parsers = {

int: (number: string) => parseInt(number, 10),

float: (number: string) => parseFloat(number),

list: (val: string) => val.split(','),

collect: (val, memo) => {

memo.push(val)

return memo

},

}

We now have all the arguments passed to our app in the execution variable. Everything seems fine, but we would also like there to be default arguments and to have an error thrown whenever the –exe argument is missing. We can ensure all the aforementioned requirements are met with a simple function called parseArguments:

const parseArguments = (execution: program.Command) => {

const { ext = [], watch = [], ignore = [], delay = 0, exe } = execution

if (!exe) {

throw new Error('No script provided')

}

return {

delay,

extensions: ext.map((e) => `.${e}`),

watchedDirectories: watch,

ignoredDirectories: [...ignore, 'node_modules', 'build'],

shouldWatchEveryDirectory: not(watch.length),

shouldWatchEveryExtension: not(ext.length),

script: exe,

}

}

With chokidar, it is very easy to listen for changes. All we have to do is simply set up a listener for the change event like this:

fromEvent(chokidar.watch(process.cwd()), 'all').pipe( // ... )

Note that we have used dirname. This is because we want to watch the files inside the directory the application was executed in and not where Nodemon‘s code resides.

Also, here we can see the first use of a RxJS observable. The fromEvent function allows us to listen for the change event. Every time the listener is executed there is a value being sent down our stream.

We pipe our stream through a set of functions that can, for example, change (map) or reject (filter) the value. Since there are a lot of them, here is a useful cheat sheet.

Chokidar, on each event, will provide us with the following information:

We are not really interested in the name of the event, but we sure do care about the path of the file. Having received the path of the file we can check if the file should cause a restart of the script.

There is, however, one problem still — namely, the path is in the following format:

/Users/wow/repositories/awesome-app/service/blabla/index.ts

and here’s what we want it to look like:

service/blabla/index.ts

Don’t worry — the previously used process.cwd() gives us the path:

/Users/wow/repositories/awesome-app

so we can just remove the duplicated part from the chokidar‘s path and receive a relative path to our application’s directory.

fromEvent(chokidar.watch(process.cwd()), 'all').pipe(

// ...

map(([event, filePath]: string[]) => {

const filename = path.basename(filePath)

const extension = path.extname(filename)

return {

event,

filename,

extension,

filePath: filePath.slice(process.cwd().length + 1),

}

}),

// ...

)

Having a path relative to the application’s directory makes it easy to filter out changes to ignored files.

By providing the –watch argument users can specify which directories they are interested in.

For example: --watch src,assets means that we ignore all the changes that have been made outside the directories src, assets. Note that it is possible still to ignore specific subdirectories.

By comparison, –ignore lets us set the directories we would like to be ignored. We are going to, by default, add node_modules and build to the directories provided by the user since we would always like them to be ignored.

const isInDirectory = (directories: string[]) => (filePath: string) =>

directories.some(filePath.startsWith.bind(filePath))

const isExpectedExtension = (extensions: string[]) => (extension: string) =>

extensions.some(is(extension))

// ...

const shouldPathBeIgnored = isInDirectory(ignoredDirectories)

const shouldPathBeWatched = isInDirectory(watchedDirectories)

const shouldExtensionBeWatched = isExpectedExtension(extensions)

// ...

fromEvent(chokidar.watch(process.cwd()), 'all').pipe(

// ...

filter(

({ filePath, extension }) =>

(shouldWatchEveryDirectory || shouldPathBeWatched(filePath)) &&

(shouldWatchEveryExtension || shouldExtensionBeWatched(extension)) &&

not(shouldPathBeIgnored(filePath)),

),

// ...

)

The rules for a file to be accepted could be laid out like this:

If the filter returns false, the value will not go any further in the stream and will be discarded. We can be sure that from then on we are only working with the files we are interested in.

Sometimes we are saving a few files one by one. This may cause many restarts of the script which in turn may use a lot of processing power. We can wait a second after the last change event is emitted so that the script restarts only once.

The technique that keeps delaying a given action is called debouncing.

fromEvent(chokidar.watch(process.cwd()), 'all').pipe( debounceTime(delay || 1000), // ... )

The debounce function is actually placed as the first function in our pipe, so we are not going to do anything until we are 100 percent sure that we have to.

Before we execute the script, it would be nice to color the messages and throw in some emojis. We are going to need a little helper for that:

const message = (content: string, color: string) => {

const msg = emoji.emojify(content)

if (colors[color]) {

return colors[color](msg)

}

return msg

}

Node.js enables us to execute commands by using the child_process module — namely, the spawn function.

After spawning the provided script we need to keep a reference to its instance so that we can kill it and spawn it again each time there is a change to the file we are keeping an eye on.

const createScriptExec = (script: string) => {

let instance = null

return async function execute() {

if (instance) {

await kill(instance, 'SIGKILL')

}

instance = spawn(script, [], { shell: true })

return merge<String, String>(

fromEvent(instance.stderr, 'data').pipe(

map((data) => message(data.toString(), 'red')),

),

fromEvent(instance.stdout, 'data').pipe(

map((data) => message(data.toString(), 'cyan')),

),

).pipe(takeUntil(fromEvent(instance, 'close')))

}

}

// ...

const executeScript = createScriptExec(script)

// ...

fromEvent(chokidar.watch(process.cwd()), 'all').pipe(

// ...

switchMap(executeScript),

tap(() => console.log(message('Executing...', 'green'))),

switchMap((obsvr) => {

return obsvr.pipe(

tap(console.log),

reduce(() => null),

)

}),

tap(() => console.log(message('Finished! :fire:', 'green'))),

)

As a result of calling executeScript, we get an observable which streams down logs of the executed script. Logs from the script (stdout) are logged in cyan. We use red to log application’s errors (stderr), and green for logs created by our application. This way it is more clear where the log came from.

At line 30 we use switchMap to get the observable mentioned above. We pipe the logs it returns through tap(console.log) to log everything to the console and reduce(() => null) to wait for the observable to be completed and move on.

After the observable finishes, we log to the user that the script has been executed.

Congratulations, you have just used a whole new way of programming to build an application!

The great thing about Reactive Extensions’ API, available in JavaScript as RxJS, is its ubiquity, which makes some of the knowledge you hopefully have gained here easily applicable to other programming languages.

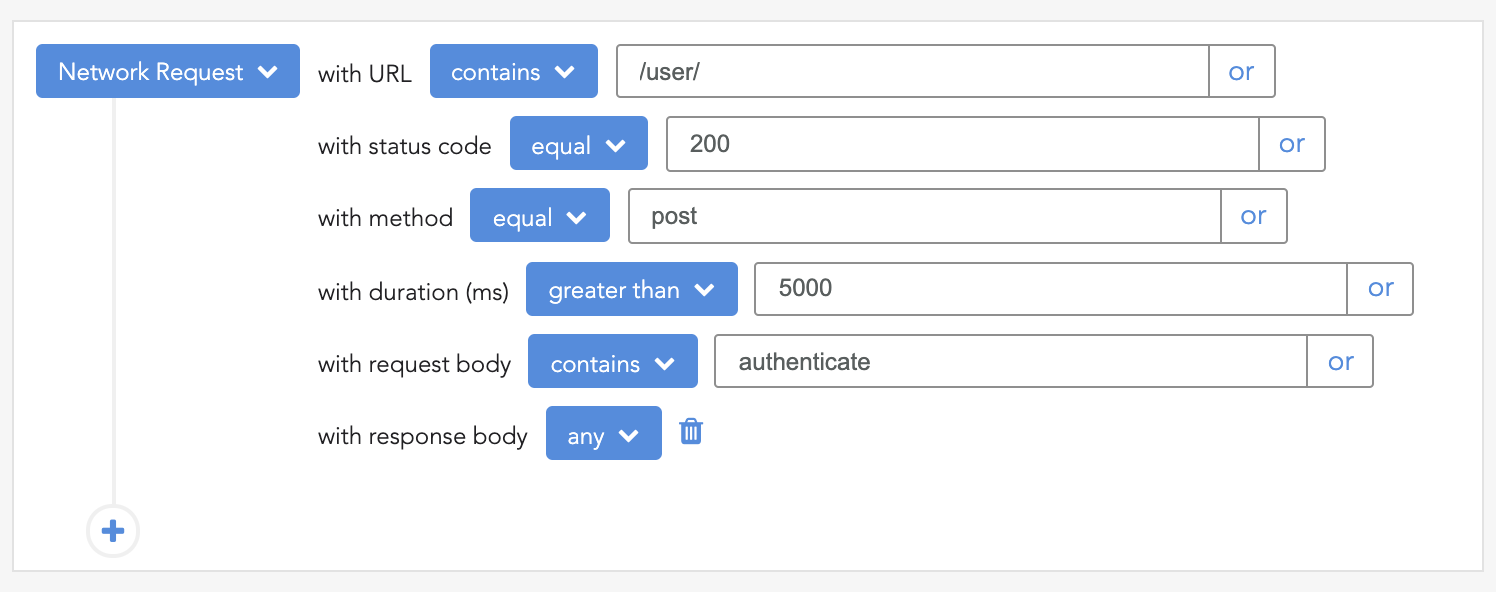

Monitor failed and slow network requests in production

Monitor failed and slow network requests in productionDeploying a Node-based web app or website is the easy part. Making sure your Node instance continues to serve resources to your app is where things get tougher. If you’re interested in ensuring requests to the backend or third-party services are successful, try LogRocket.

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork around why bugs happen by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings — compatible with all frameworks.

LogRocket's Galileo AI watches sessions for you, instantly identifying and explaining user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

LogRocket instruments your app to record baseline performance timings such as page load time, time to first byte, slow network requests, and also logs Redux, NgRx, and Vuex actions/state. Start monitoring for free.

Signal Forms in Angular 21 replace FormGroup pain and ControlValueAccessor complexity with a cleaner, reactive model built on signals.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the February 25th issue.

Explore how the Universal Commerce Protocol (UCP) allows AI agents to connect with merchants, handle checkout sessions, and securely process payments in real-world e-commerce flows.

React Server Components and the Next.js App Router enable streaming and smaller client bundles, but only when used correctly. This article explores six common mistakes that block streaming, bloat hydration, and create stale UI in production.

Would you be interested in joining LogRocket's developer community?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now