Everyone knows about Docker. It’s the ubiquitous tool for packaging and distribution of applications that seemed to come from nowhere and take over our industry! If you are reading this, it means you already understand the basics of Docker and are now looking to create a more complex build pipeline.

In the past, optimizing our Docker images has been a challenging experience. All sorts of magic tricks were employed to reduce the size of our applications before they went to production. Things are different now because support for multi-stage builds has been added to Docker.

In this post, we explore how you can use a multi-stage build for your Node.js application. For an example, we’ll use a TypeScript build process, but the same kind of thing will work for any build pipeline. So even if you’d prefer to use Babel, or maybe you need to build a React client, then a Docker multi-stage build can work for you as well.

The code that accompanies this post is available on GitHub, where you can find an example Dockerfile with a multi-stage TypeScript build.

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

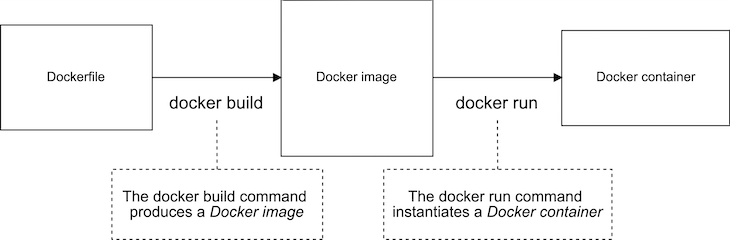

Let’s start by looking at a basic Dockerfile for Node.js. We can visualize the normal Docker build process as shown in Figure 1 below.

We use the docker build command to turn our Dockerfile into a Docker image. We then use the docker run command to instantiate our image to a Docker container.

The Dockerfile in Listing 1 below is just a standard, run-of-the-mill Dockerfile for Node.js. You have probably seen this kind of thing before. All we are doing here is copying the package.json, installing production dependencies, copying the source code, and finally starting the application.

This Dockerfile is for regular JavaScript applications, so we don’t need a build process yet. I’m only showing you this simple Dockerfile so you can compare it to the multi-stage Dockerfile I’ll be showing you soon.

FROM node:10.15.2 WORKDIR /usr/src/app COPY package*.json ./ RUN npm install --only=production COPY ./src ./src EXPOSE 3000 CMD npm start

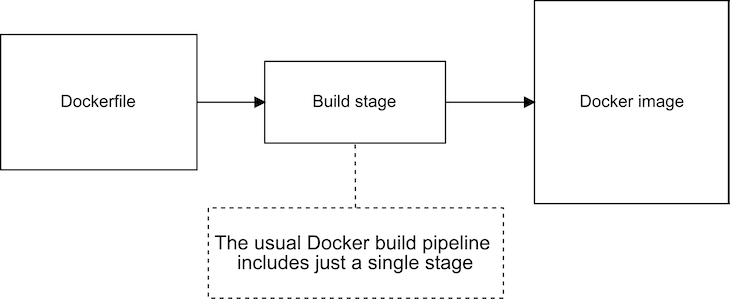

Listing 1 is a quite ordinary-looking Docker file. In fact, all Docker files looked pretty much like this before multi-stage builds were introduced. Now that Docker supports multi-stage builds, we can visualize our simple Dockerfile as the single-stage build process illustrated in Figure 2.

We can already run whatever commands we want in the Dockerfile when building our image, so why do we even need a multi-stage build?

To find out why, let’s upgrade our simple Dockerfile to include a TypeScript build process. Listing 2 shows the upgraded Dockerfile. I’ve bolded the updated lines so you can easily pick them out.

FROM node:10.15.2 WORKDIR /usr/src/app COPY package*.json ./ COPY tsconfig.json ./ RUN npm install COPY ./src ./src RUN npm run build EXPOSE 80 CMD npm start

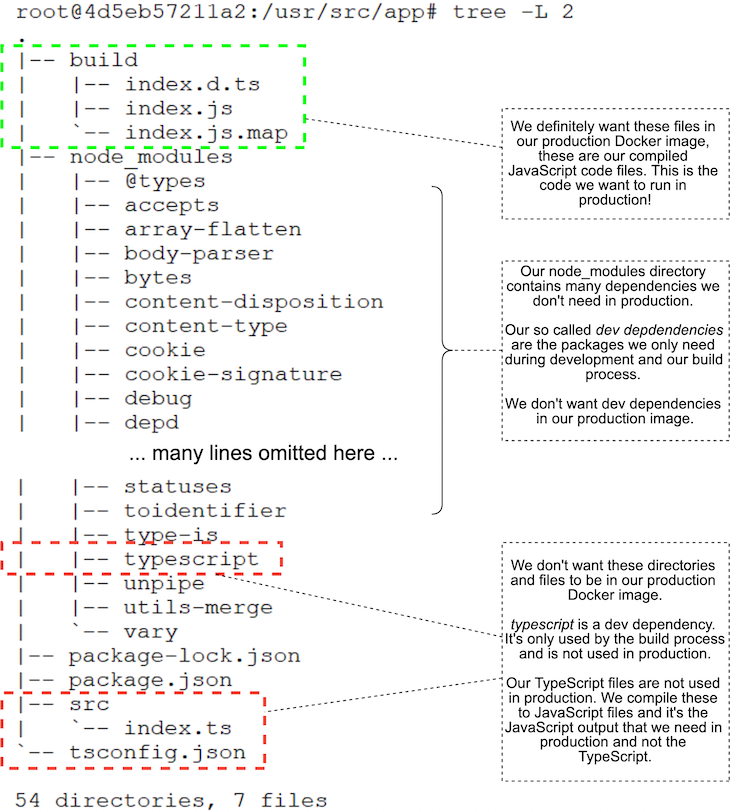

We can easily and directly see the problem this causes. To see it for yourself, you should instantiate a container from this image and then shell into it and inspect its file system.

I did this and used the Linux tree command to list all the directories and files in the container. You can see the result in Figure 3.

Notice that we have unwittingly included in our production image all the debris of development and the build process. This includes our original TypeScript source code (which we don’t use in production), the TypeScript compiler itself (which, again, we don’t use in production), plus any other dev dependencies we might have installed into our Node.js project.

Bear in mind this is only a trivial project, so we aren’t actually seeing too much cruft left in our production image. But you can imagine how bad this would be for a real application with many sources files, many dev dependencies, and a more complex build process that generates temporary files!

We don’t want this extra bloat in production. The extra size makes our containers bigger. When our containers are bigger than needed, it means we aren’t making efficient use of our resources. The increased surface area of the container can also be a problem for security, where we generally prefer to minimize the attackable surface area of our application.

Wouldn’t it be nice if we could throw away the files we don’t want and just keep the ones we do want? This is exactly what a Docker multi-stage build can do for us.

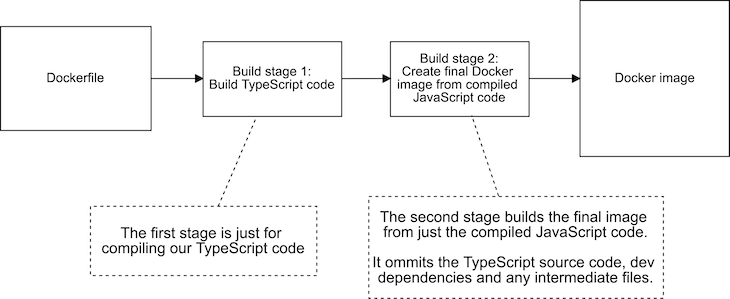

We are going to split out Dockerfile into two stages. Figure 4 shows what our build pipeline looks like after the split.

Our new multi-stage build pipeline has two stages: Build stage 1 is what builds our TypeScript code; Build stage 2 is what creates our production Docker image. The final Docker image produced at the end of this pipeline contains only what it needs and omits the cruft we don’t want.

To create our two-stage build pipeline, we are basically just going to create two Docker files in one. Listing 3 shows our Dockerfile with multiple stages added. The first FROM command initiates the first stage, and the second FROM command initiates the second stage.

Compare this to a regular single-stage Dockerfile, and you can see that it actually looks like two Dockerfiles squished together in one.

# # Build stage 1. # This state builds our TypeScript and produces an intermediate Docker image containing the compiled JavaScript code. # FROM node:10.15.2 WORKDIR /usr/src/app COPY package*.json ./ COPY tsconfig.json ./ RUN npm install COPY ./src ./src RUN npm run build # # Build stage 2. # This stage pulls the compiled JavaScript code from the stage 1 intermediate image. # This stage builds the final Docker image that we'll use in production. # FROM node:10.15.2 WORKDIR /usr/src/app COPY package*.json ./ RUN npm install --only=production COPY --from=0 /usr/src/app/build ./build EXPOSE 80 CMD npm start

To create this multi-stage Dockerfile, I simply took Listing 2 and divided it up into separate Dockerfiles. The first stage contains only what is need to build the TypeScript code. The second stage contains only what is needed to produce the final production Docker image. I then merged the two Dockerfiles into a single file.

The most important thing to note is the use of --from in the second stage. I’ve bolded this line in Listing 3 so you can easily pick it out. This is the syntax we use to pull the built files from our first stage, which we refer to here as stage 0. We are pulling the compiled JavaScript files from the first stage into the second stage.

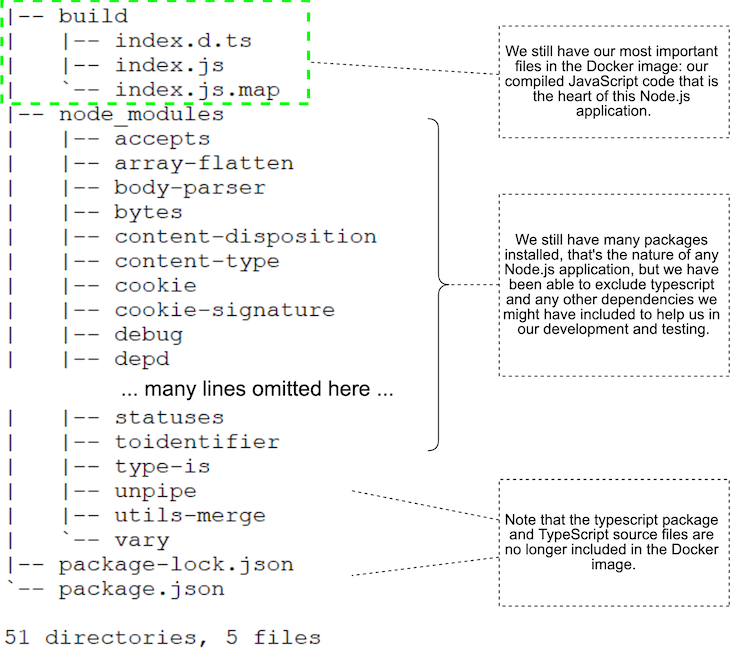

We can easily check to make sure we got the desired result. After creating the new image and instantiating a container, I shelled in to check the contents of the file system. You can see in Figure 5 that we have successfully removed the debris from our production image.

We now have fewer files in our image, it’s smaller, and it has less surface area. Yay! Mission accomplished.

But what, specifically, does this mean?

What exactly is the effect of the new build pipeline on our production image?

I measured the results before and after. Our single-stage image produced by Listing 2 weighs in at 955MB. After converting to the multi-stage build in Listing 3, the image now comes to 902MB. That’s a reasonable reduction — we removed 53MB from our image!

While 53MB seems like a lot, we have actually only shaved off just more than 5 percent of the size. I know what you’re going to say now: But Ash, our image is still monstrously huge! There’s still way too much bloat in that image.

Well, to make our image even smaller, we now need to use the alpine, or slimmed-down, Node.js base image. We can do this by changing our second build stage from node:10.15.2 to node:10.15.2-alpine.

This reduces our production image down to 73MB — that’s a huge win! Now the savings we get from discarding our debris is more like a whopping 60 percent. Alright, we are really getting somewhere now!

This highlights another benefit of multi-stage builds: we can use separate Docker base images for each of our build stages. This means you can customize each build stage by using a different base image.

Say you have one stage that relies on some tools that are in a different image, or you have created a special Docker image that is custom for your build process. This gives us a lot of flexibility when constructing our build pipelines.

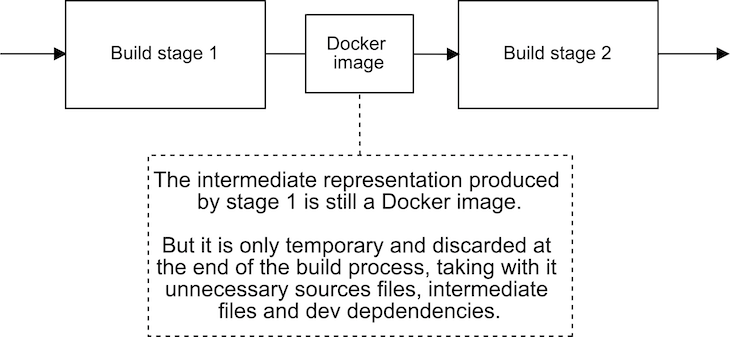

You probably already guessed this: each stage or build process produces its own separate Docker image. You can see how this works in Figure 6.

The Docker image produced by a stage can be used by the following stages. Once the final image is produced, all the intermediate images are discarded; we take what we want for the final image, and the rest gets thrown away.

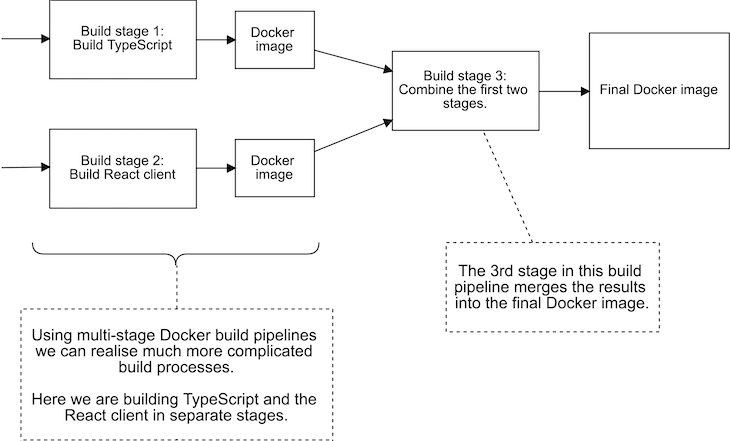

There’s no need to stop at two stages, although that’s often all that’s needed; we can add as many stages as we need. A specific example is illustrated in Figure 7.

Here we are building TypeScript code in stage 1 and our React client in stage 2. In addition, there’s a third stage that produces the final image from the results of the first two stages.

Now time to leave you with a few advanced tips to explore on your own:

Docker multi-stage builds enable us to create more complex build pipelines without having to resort to magic tricks. They help us slim down our production Docker images and remove the bloat. They also allow us to structure and modularize our build process, which makes it easier to test parts of our build process in isolation.

So please have some fun with Docker multi-stage builds, and don’t forget to have a look at the example code on GitHub.

Here’s the Docker documentation on multi-stage builds, too.

Ashley Davis is an experienced software developer and author. He is CTO of Sortal and helping businesses manage their digital assets using machine learning.

Ash is also the developer of Data-Forge Notebook, a notebook-style application for prototyping, exploratory coding, and data analysis in JavaScript and TypeScript.

Ash is the author of Data Wrangling with JavaScript and Bootstrapping Microservices. To keep up to date with Ash’s work, please follow him on Twitter and keep an eye on his blog, The Data Wrangler.

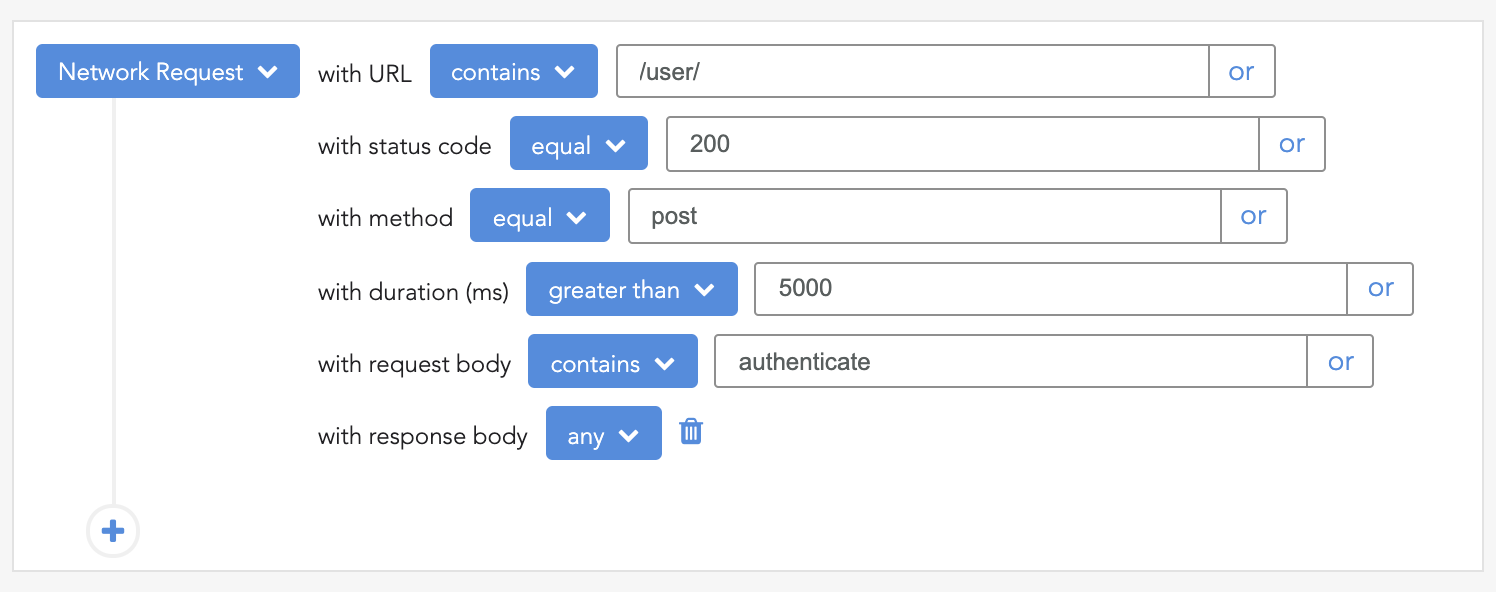

Monitor failed and slow network requests in production

Monitor failed and slow network requests in productionDeploying a Node-based web app or website is the easy part. Making sure your Node instance continues to serve resources to your app is where things get tougher. If you’re interested in ensuring requests to the backend or third-party services are successful, try LogRocket.

LogRocket lets you replay user sessions, eliminating guesswork around why bugs happen by showing exactly what users experienced. It captures console logs, errors, network requests, and pixel-perfect DOM recordings — compatible with all frameworks.

LogRocket's Galileo AI watches sessions for you, instantly identifying and explaining user struggles with automated monitoring of your entire product experience.

LogRocket instruments your app to record baseline performance timings such as page load time, time to first byte, slow network requests, and also logs Redux, NgRx, and Vuex actions/state. Start monitoring for free.

@container scroll-state: Replace JS scroll listeners nowCSS @container scroll-state lets you build sticky headers, snapping carousels, and scroll indicators without JavaScript. Here’s how to replace scroll listeners with clean, declarative state queries.

Explore 10 Web APIs that replace common JavaScript libraries and reduce npm dependencies, bundle size, and performance overhead.

Russ Miles, a software development expert and educator, joins the show to unpack why “developer productivity” platforms so often disappoint.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the February 18th issue.

Would you be interested in joining LogRocket's developer community?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now