React, Angular, and Vue are excellent frameworks for getting web applications up and running quickly with consistent structures. They are all built on top of JavaScript though, so let’s take a look at how we can do the nice things that the big frameworks do, using only vanilla JavaScript.

This article may be of interest to developers who have used these frameworks in the past but never quite understood what they’re doing under the hood. We’ll explore different aspects of these frameworks by demonstrating how to build a stateful web app using only vanilla JavaScript.

Jump ahead:

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

Managing state is something that React, Angular, and Vue do internally or via libraries such as Redux or Zustand. However, state can be as simple as a JavaScript object containing all the property-value key pairs that are of interest to your app.

If you’re building the classic to-do list app, your state will probably contain a property like currentTodoItemID and if its value is null, your app might display the full list of all the to-do items.

If currentTodoItemID is set to the ID of a particular todoItem, the app might display that todoItem's details. If you’re building a game, your state may contain properties and values such as playerHealth = 47.5 and currentLevel = 2.

It doesn’t really matter the shape or size of the state; what’s important is how your app’s components change its properties and how other components react to those changes.

This brings us to our first bit of magic: the Proxy object.

Proxy objects are native to JavaScript starting with ES6 and can be used to monitor an object for changes. To see how to leverage proxy objects in JavaScript, let’s look at some example code in the below index.js file using an npm module called on-change.

import onChange from 'on-change';

class App = {

constructor() {

// create the initial state object

const state = {

currentTodoItemID: null

}

// listen for changes to the state object

this.state = onChange(state, this.update);

}

// react to state changes

update(path, current, previous) {

console.log(`${path} changed from ${previous} to ${current}`);

}

}

// create a new instance of the App

const app = new App();

// this should log "currentTodoItemID changed from null to 1"

app.state.currentTodoItemID = 1;

N.B., Proxy objects will not work in Internet Explorer, so if that’s a requirement for your project you should take this warning into consideration. There’s no way to polyfill a proxy object, so you would need to use polling and check the state object several times per second to see if it has changed, which is not elegant or efficient.

Components in React are just modular bits of HTML for structure, JavaScript for logic, and CSS for styling. Some are meant to be displayed on their own, some are meant to be displayed in sequence, and some might only use HTML to house something completely different like an updatable SVG image or a WebGL canvas.

No matter what type of component you’re building, it should be able to access your app’s state or at least the parts of the state that pertain to it. The below code is from src/index.js):

import onChange from 'on-change';

import TodoItemList from 'components/TodoItemList';

class App = {

constructor() {

const state = {

currentTodoItemID: null,

todoItems: [] // *see note below

}

this.state = onChange(state, this.update);

// create a container for the app

this.el = document.createElement('div');

this.el.className = 'todo';

// create a TodoItemList, pass it the state object, and add it to the DOM

this.todoItemList = new TodoItemList(this.state);

this.el.appendChild(this.todoItemList.el);

}

update(path, current, previous) {

console.log(`${path} changed from ${previous} to ${current}`);

}

}

const app = new App();

document.body.appendChild(app.el);

As your app scales up, it’s good practice to move things like state.todoItems, which may grow quite large, outside of your state object, to a persistent storage method like a database.

Keeping references to these components in state, as shown below in src/components/TodoItemList.js and src/components/TodoItem.js, is better.

import TodoItem from 'components/TodoItem';

export default class TodoItemList {

constructor(state) {

this.el = document.createElement('div');

this.el.className = 'todo-list';

for(let i = 0; i < state.todoItems.length; i += 1) {

const todoItem = new TodoItem(state, i);

this.el.appendChild(todoItem);

}

}

}

export default class TodoItem {

constructor(state, id) {

this.el = document.createElement('div');

this.el.className = 'todo-list-item';

this.title = document.createElement('h1');

this.button = document.createElement('button');

this.title.innerText = state.todoItems[id].title;

this.button.innerText = 'Open';

this.button.addEventListener('click', () => { state.currentTodoItemID = id });

this.el.appendChild(this.title);

this.el.appendChild(this.button);

}

}

React also has the concept of views which are similar to components but do not require any logic. We can build similar containers using this vanilla pattern. I won’t include any specific examples but they can be thought of as framing components that simply pass the app’s state through to the functional components within.

DOM manipulation is an area where frameworks like React really shine. So, while we gain a little flexibility by handling the markup on our own in vanilla JavaScript, we lose a lot of the convenience associated with how these frameworks update things.

Let’s try it out in our to-do app example to see what I’m talking about. The below code is from src/index.js and src/components/TodoItemList.js:

import onChange from 'on-change';

import TodoItemList from 'components/TodoItemList';

class App = {

constructor() {

const state = {

currentTodoItemID: null,

todoItems: [

{ title: 'Buy Milk', due: '3/11/23' },

{ title: 'Wash Car', due: '4/13/23' },

{ title: 'Pay Rent', due: '5/15/23' },

]

}

this.state = onChange(state, this.update);

this.el = document.createElement('div');

this.el.className = 'todo';

this.todoItemList = new TodoItemList(this.state);

this.el.appendChild(this.todoItemList.el);

}

update(path, current, previous) {

if(path === 'todoItems') {

this.todoItemList.render();

}

}

}

const app = new App();

document.body.appendChild(app.el);

app.state.todoItems.splice(1, 1); // remove the second todoListItem

app.state.todoItems.push({ title: 'Eat Pizza', due: '6/17/23'); // add a new one

import TodoItem from 'components/TodoItem';

export default class TodoItemList {

constructor(state) {

this.state = state;

this.el = document.createElement('div');

this.el.className = 'todo-list';

this.render();

}

// render the list of todoItems to the DOM

render() {

// empty the list

this.el.innerHTML = '';

// fill the list with todoItems

for (let i = 0; i < this.state.todoItems.length; i += 1) {

const todoItem = new TodoItem(state, i);

this.el.appendChild(todoItem);

}

}

}

In the above example, we create a TodoItemList with three preloaded todoListItems in our state. Then, we delete the middle TodoItem and add a new one.

While this strategy will work and display properly, it’s inefficient since it involves deleting all the existing DOM nodes and creating new ones on each render.

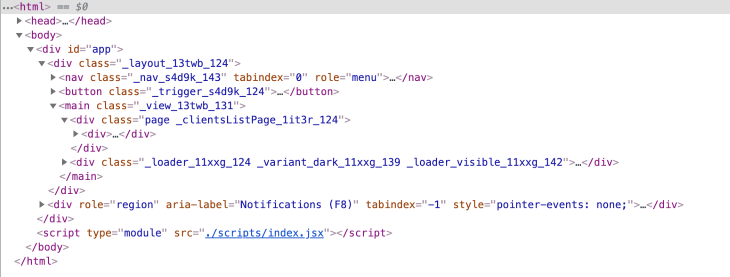

React is smarter than JavaScript in this regard; it keeps references to each DOM node in memory. You’ve probably noticed strange identifiers in React markup, like those shown below:

We can make similar DOM manipulations by storing references to each node as well. For todoListItems, it might look something like this:

for(let i = 0; i < this.state.todoItems.length; i += 1) {

// instead of making anonymous elements, attach them to state

this.state.todoItems[i].el = new TodoItem(this.state, i);

this.el.appendChild(this.state.todoItems[i].el);

}

While these manipulations will work, you should be careful when adding DOM elements to your state. They are more than just references to their place in the DOM tree; they contain their own properties and methods which may change throughout the lifecycle of your app.

If you go this route, it’s best to use the ignoreKeys parameter to tell the on-change module to ignore the added DOM elements.

React has a consistent set of lifecycle Hooks, making it very easy for a developer to start working on a new project and quickly understand what will happen while the app is running. The two most notable Hooks are ComponentDidMount() and ComponentWillUnmount().

Let’s take a very basic example, in the src/index.js file and simply call them show() and hide().

import onChange from 'on-change';

import Menu from 'components/Menu';

class App = {

constructor() {

const state = {

showMenu: false

}

this.state = onChange(state, this.update);

this.el = document.createElement('div');

this.el.className = 'todo';

// create an instance of the Menu

this.menu = new Menu(this.state);

// create a button to show or hide the menu

this.toggle = document.createElement('button');

this.toggle.innerText = 'show or hide the menu';

this.el.appendChild(this.menu.el);

this.el.appendChild(this.toggle);

// change the showMenu property of our state object when clicked

this.toggle.addEventListener('click', () => { this.state.showMenu = !this.state.showMenu; })

}

update(path, current, previous) {

if(path === 'showMenu') {

// show or hide menu depending on state

this.menu[current ? 'show' : 'hide']();

}

}

}

const app = new App();

document.body.appendChild(app.el);

Now, here’s an example (from src/components/menu.js) of how we might write custom Hooks in JavaScript:

export default class Menu = {

constructor(state) {

this.el = document.createElement('div');

this.title = document.createElement('h1');

this.text = document.createElement('p');

this.title.innerText = 'Menu';

this.text.innerText = 'menu content here';

this.el.appendChild(this.title);

this.el.appendChild(this.text);

this.el.className = `menu ${!state.showMenu ? 'hidden' : ''}`;

}

show() {

this.el.classList.remove('hidden');

}

hide() {

this.el.classList.add('hidden');

}

}

This strategy allows us to write any internal methods we like. For example, you might want to change the way the menu animates based on whether it was closed by the user, or closed because something else happened in the app.

React enforces consistency by using a standard set of Hooks, but we have more flexibility by being able to write custom hooks in vanilla JavaScript for our components.

An important aspect of modern web apps is being able to keep track of the current location and move both back and forward in history, either by using the app’s UI or the browser’s back and forward buttons. It’s also nice when your app respects “deep links” such as https://todoapp.com/currentTodoItem/5.

React Router works great for this and we can do something similar using a few techniques. One is JavaScript’s native history API. By pushing to and popping from its array we can keep track of state changes that we want to persist into the page’s history. We can also listen to changes from it and apply those changes to our state object (below code is from index.js.

import onChange from 'on-change';

class App = {

constructor() {

// create the initial state object

const state = {

currentTodoItemID: null

}

// listen for changes to the state object

this.state = onChange(state, this.update);

// listen for changes to the page location

window.addEventListener('popstate', () => {

this.state.currentTodoItemID = window.location.pathname.split('/')[2];

});

// on first load, check for a deep link

if(window.location.pathname.split('/')[2]) {

this.state.currentTodoItemID = window.location.pathname.split('/')[2];

}

}

// react to state changes

update(path, current, previous) {

console.log(`${path} changed from ${previous} to ${current}`);

if(path === 'currentTodoItemID') {

history.pushState({ currentTodoItemID: current }, null, `/currentTodoItemID/${current}`);

}

}

}

// create a new instance of the App

const app = new App();

You can extend this as much as you like; for complex apps, you may have 10 or more different properties that affect what it should display. This technique takes a bit more setup than React Router but achieves the same results using vanilla JavaScript.

Another nice byproduct of React is how it encourages you to organize your directories and files starting with an entry point, often named index.js or app.js, near the root of the project folder.

Next, you’ll typically find /views and /components folders in the same location, filled with the various views and components the app will leverage, as well as maybe a few /subviews or /subcomponents.

This clear division makes it easier for the original author, or new developers who have joined the project, to make updates.

Here’s a sample folder structure for a to-do list app:

src ├── assets │ ├── images │ ├── videos │ └── fonts ├── components │ ├── TodoItem.js │ ├── TodoItem.scss │ ├── TodoItemList.js │ └── TodoItemList.scss ├── views │ ├── nav.js │ ├── header.js │ ├── main.js │ └── footer.js ├── index.js └── index.scss

In my apps, I typically create the markup via JavaScript so that I have a reference to it, but you could also use your favorite templating engine or even include .html files to scaffold each component.

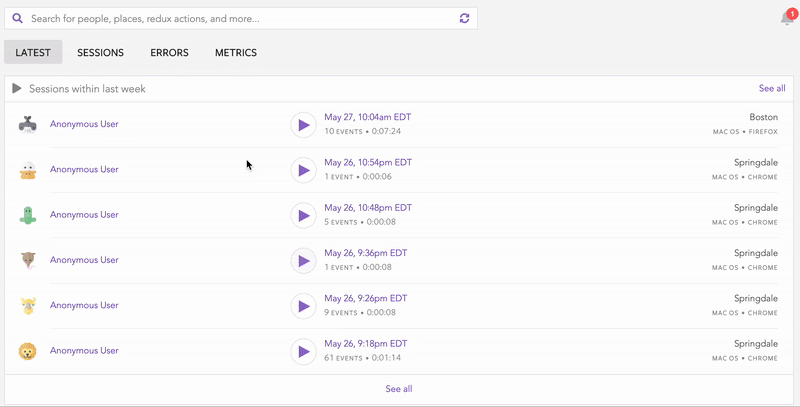

React has a suite of debugging tools that will run in Chrome’s developer console.

With this vanilla JavaScript approach, you can create some middleware inside onChange’s listener which you can set up to do a lot of similar things. Personally, I like to just console all the changes to state when the app sees that it’s running locally (window.location.hostname === 'localhost').

Sometimes, you want to focus only on specific changes or components and that’s easy enough too.

Obviously, there are huge advantages to learning and using the big frameworks, but remember, they are all written in JavaScript. It’s important that we don’t become dependent on them.

There is an entire army of React, Angular, or Vue developers who manage to eschew learning the foundations of JavaScript and that’s okay if all they want to do is work on React, Angular, or Vue projects. For the rest of us, it’s good to be aware of the underlying language, its capabilities, and its shortcomings.

I hope this article gave you a little insight into how these larger frameworks work and gave you some ideas for how to debug them when they don’t.

Please use the comments below to make suggestions for how to improve this system or call out any mistakes I’ve made. I’ve found this setup to be an intuitive and thin layer of scaffolding that supports apps of all sizes and functionality, but I continue to evolve it with every project.

Often other developers will see my apps and assume I’m using one of the big frameworks. When they ask “what’s this built with?”, it’s nice to be able to respond with “JavaScript” 🙂

Debugging code is always a tedious task. But the more you understand your errors, the easier it is to fix them.

LogRocket allows you to understand these errors in new and unique ways. Our frontend monitoring solution tracks user engagement with your JavaScript frontends to give you the ability to see exactly what the user did that led to an error.

LogRocket records console logs, page load times, stack traces, slow network requests/responses with headers + bodies, browser metadata, and custom logs. Understanding the impact of your JavaScript code will never be easier!

Solve coordination problems in Islands architecture using event-driven patterns instead of localStorage polling.

Signal Forms in Angular 21 replace FormGroup pain and ControlValueAccessor complexity with a cleaner, reactive model built on signals.

Discover what’s new in The Replay, LogRocket’s newsletter for dev and engineering leaders, in the February 25th issue.

Explore how the Universal Commerce Protocol (UCP) allows AI agents to connect with merchants, handle checkout sessions, and securely process payments in real-world e-commerce flows.

Would you be interested in joining LogRocket's developer community?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

2 Replies to "Building stateful web apps without React"

Thanks for a thorough article

Great. When I’m working on React and am focusing on the “framework”, I sometimes forget that I’m using ‘javascript’. This post reminds that. Thanks