With the introduction of ES6, iterators and generators have officially been added to JavaScript.

Iterators allow you to iterate over any object that follows the specification. In the first section, we will see how to use iterators and make any object iterable.

The second part of this blog post focuses entirely on generators: what they are, how to use them, and in which situations they can be useful.

I always like to look at how things work under the hood: In a previous blog series, I explained how JavaScript works in the browser. As a continuation of that, I want to explain how JavaScript’s iterators and generators work in this article.

The Replay is a weekly newsletter for dev and engineering leaders.

Delivered once a week, it's your curated guide to the most important conversations around frontend dev, emerging AI tools, and the state of modern software.

Before we can understand generators, we need a thorough understanding of iterators in JavaScript, as these two concepts go hand-in-hand. After this section, it will become clear that generators are simply a way to write iterators more securely.

As the name already gives away, iterators allow you to iterate over an object (arrays are also objects).

Most likely, you have already used JavaScript iterators. Every time you iterated over an array, for example, you have used iterators, but you can also iterate over Map objects and even over strings.

for (let i of 'abc') {

console.log(i);

}

// Output

// "a"

// "b"

// "c"

Any object that implements the iterable protocol can be iterated on by using “for…of”.

Digging a bit deeper, you can make any object iterable by implementing the @@iterator function, which returns an iterator object.

To understand this correctly, it’s probably best to look at an example of making a regular object iterable.

We start with an object that contains user names grouped by city:

const userNamesGroupedByLocation = {

Tokio: [

'Aiko',

'Chizu',

'Fushigi',

],

'Buenos Aires': [

'Santiago',

'Valentina',

'Lola',

],

'Saint Petersburg': [

'Sonja',

'Dunja',

'Iwan',

'Tanja',

],

};

I took this example because it’s not easy to iterate over the users if the data is structured this way; to do so, we would need multiple loops to get all users.

If we try to iterate over this object as it is, we will get the following error message:

▶ Uncaught ReferenceError: iterator is not defined

To make this object iterable, we first need to add the @@iterator function. We can access this symbol via Symbol.iterator.

userNamesGroupedByLocation[Symbol.iterator] = function() {

// ...

}

As I mentioned before, the iterator function returns an iterator object. The object contains a function under next, which also returns an object with two attributes: done and value.

userNamesGroupedByLocation[Symbol.iterator] = function() {

return {

next: () => {

return {

done: true,

value: 'hi',

};

},

};

}

value contains the current value of the iteration, while done is a boolean that tells us if the execution has finished.

When implementing this function, we need to be especially careful about the done value, as it is always returning false will result in an infinite loop.

The code example above already represents a correct implementation of the iterable protocol. We can test it by calling the next function of the iterator object.

// Calling the iterator function returns the iterator object const iterator = userNamesGroupedByLocation[Symbol.iterator](); console.log(iterator.next().value); // "hi"

Iterating over an object with “for…of” uses the

nextfunction under the hood.

Using “for…of” in this case won’t return anything because we immediately set done to false. We also don’t get any user names by implementing it this way, which is why we wanted to make this object iterable in the first place.

First of all, we need to access the keys of the object that represent cities. We can get this by calling Object.keys on the this keyword, which refers to the parent of the function, which, in this case, is the userNamesGroupedByLocation object.

We can only access the keys through this if we defined the iterable function with the function keyword. If we used an arrow function, this wouldn’t work because they inherit their parent’s scope.

const cityKeys = Object.keys(this);

We also need two variables that keep track of our iterations.

let cityIndex = 0; let userIndex = 0;

We define these variables in the iterator function but outside of the

nextfunction, which allows us to keep the data between iterations.

In the next function, we first need to get the array of users of the current city and the current user, using the indexes we defined before.

We can use this data to change the return value now.

return {

next: () => {

const users = this[cityKeys[cityIndex]];

const user = users[userIndex];

return {

done: false,

value: user,

};

},

};

Next, we need to increment the indexes with every iteration.

We increment the user index every time unless we have arrived at the last user of a given city, in which case we will set userIndex to 0 and increment the city index instead.

return {

next: () => {

const users = this[cityKeys[cityIndex]];

const user = users[userIndex];

const isLastUser = userIndex >= users.length - 1;

if (isLastUser) {

// Reset user index

userIndex = 0;

// Jump to next city

cityIndex++

} else {

userIndex++;

}

return {

done: false,

value: user,

};

},

};

Be careful not to iterate on this object with “for…of”. Given that done always equals false, this will result in an infinite loop.

The last thing we need to add is an exit condition that sets done to true. We exit the loop after we have iterated over all cities.

if (cityIndex > cityKeys.length - 1) {

return {

value: undefined,

done: true,

};

}

After putting everything together, our function then looks like the following:

userNamesGroupedByLocation[Symbol.iterator] = function() {

const cityKeys = Object.keys(this);

let cityIndex = 0;

let userIndex = 0;

return {

next: () => {

// We already iterated over all cities

if (cityIndex > cityKeys.length - 1) {

return {

value: undefined,

done: true,

};

}

const users = this[cityKeys[cityIndex]];

const user = users[userIndex];

const isLastUser = userIndex >= users.length - 1;

userIndex++;

if (isLastUser) {

// Reset user index

userIndex = 0;

// Jump to next city

cityIndex++

}

return {

done: false,

value: user,

};

},

};

};

This allows us to quickly get all the names out of our object using a “for…of” loop.

for (let name of userNamesGroupedByLocation) {

console.log('name', name);

}

// Output:

// name Aiko

// name Chizu

// name Fushigi

// name Santiago

// name Valentina

// name Lola

// name Sonja

// name Dunja

// name Iwan

// name Tanja

As you can see, making an object iterable is not magic. However, it needs to be done very carefully because mistakes in the next function can easily lead to an infinite loop.

If you want to learn more about the behavior, I encourage you to try to make an object of your choice iterable as well. You can find an executable version of the code in this tutorial on this codepen.

To sum up what we did to create an iterable, here are the steps again we followed:

@@iterator key (accessible through Symbol.iteratornext functionnext function returns an object with the attributes done and valueWe have learned how to make any object iterable, but how does this relate to generators?

While iterators are a powerful tool, it’s not common to create them as we did in the example above. We need to be very careful when programming iterators, as bugs can have serious consequences, and managing the internal logic can be challenging.

Generators are a useful tool that allows us to create iterators by defining a function.

This approach is less error-prone and allows us to create iterators more efficiently.

An essential characteristic of generators and iterators is that they allow you to stop and continue execution as needed. We will see a few examples in this section that make use of this feature.

Creating a generator function is very similar to regular functions. All we need to do is add an asterisk (*) in front of the name.

function *generator() {

// ...

}

If we want to create an anonymous generator function, this asterisk moves to the end of the function keyword.

function* () {

// ...

}

yield keywordDeclaring a generator function is only half of the work and not very useful on its own.

As mentioned, generators are an easier way to create iterables. But how does the iterator know over which part of the function it should iterate? Should it iterate over every single line?

That is where the yield keyword comes into play. You can think of it as the await keyword you may know from JavaScript Promises, but for generators.

We can add this keyword to every line where we want the iteration to stop. The next function will then return the result of that line’s statement as part of the iterator object ({ done: false, value: 'something' }).

function* stringGenerator() {

yield 'hi';

yield 'hi';

yield 'hi';

}

const strings = stringGenerator();

console.log(strings.next());

console.log(strings.next());

console.log(strings.next());

console.log(strings.next());

The output of this code will be the following:

{value: "hi", done: false}

{value: "hi", done: false}

{value: "hi", done: false}

{value: undefined, done: true}

Calling stringGenerator won’t do anything on its own because it will automatically stop the execution at the first yield statement.

Once the function reaches its end, value equals undefined, and done is automatically set to true.

If we add an asterisk to the yield keyword, we delegate the execution to another iterator object.

For example, we could use this to delegate to another function or array:

function* nameGenerator() {

yield 'Iwan';

yield 'Aiko';

}

function* stringGenerator() {

yield* nameGenerator();

yield* ['one', 'two'];

yield 'hi';

yield 'hi';

yield 'hi';

}

const strings = stringGenerator();

for (let value of strings) {

console.log(value);

}

The code produces the following output:

Iwan Aiko one two hi hi hi

The next function that the iterator returns for generators has an additional feature: it allows you to overwrite the returned value.

Taking the example from before, we can override the value that yield would have returned otherwise.

function* overrideValue() {

const result = yield 'hi';

console.log(result);

}

const overrideIterator = overrideValue();

overrideIterator.next();

overrideIterator.next('bye');

We need to call

nextonce before passing a value to start the generator.

Apart from the “next” method, which any iterator requires, generators also provide a return and throw function.

Calling return instead of next on an iterator will cause the loop to exit on the next iteration.

Every iteration that comes after calling return will set done to true and value to undefined.

If we pass a value to this function, it will replace the value attribute on the iterator object.

This example from the Web MDN docs illustrates it perfectly:

function* gen() {

yield 1;

yield 2;

yield 3;

}

const g = gen();

g.next(); // { value: 1, done: false }

g.return('foo'); // { value: "foo", done: true }

g.next(); // { value: undefined, done: true }

Generators also implement a throw function, which, instead of continuing with the loop, will throw an error and terminate the execution:

function* errorGenerator() {

try {

yield 'one';

yield 'two';

} catch(e) {

console.error(e);

}

}

const errorIterator = errorGenerator();

console.log(errorIterator.next());

console.log(errorIterator.throw('Bam!'));

The output of the code above is the following:

{value: 'one', done: false}

Bam!

{value: undefined, done: true}

If we try to iterate further after throwing an error, the returned value will be undefined, and done will be set to true.

As we have seen in this article, we can use generators to create iterables. The topic may sound very abstract, and I have to admit that I rarely need to use generators myself.

However, some use cases benefit from this feature immensely. These cases typically make use of the fact that you can pause and resume the execution of generators.

This one is my favorite use case because it fits generators perfectly.

Generating unique and incremental IDs requires you to keep track of the IDs that have been generated.

With a generator, you can create an infinite loop that creates a new ID with every iteration.

Every time you need a new ID, you can call the next function, and the generator takes care of the rest:

function* idGenerator() {

let i = 0;

while (true) {

yield i++;

}

}

const ids = idGenerator();

console.log(ids.next().value); // 0

console.log(ids.next().value); // 1

console.log(ids.next().value); // 2

console.log(ids.next().value); // 3

console.log(ids.next().value); // 4

Thank you, Nick, for the idea.

There are many other use cases as well. As I have discovered in this article, finite state machines can also make use of generators.

Quite a few libraries use generators as well, such as Mobx-State-Tree or Redux-Saga, for instance.

Have you come across any other interesting use cases? Let me know in the comment section below.

Generators and iterators may not be something we need to use every day, but when we encounter situations that require their unique capabilities, knowing how to use them can be of great advantage.

In this article, we learned about iterators and how to make any object iterable. In the second section, we learned what generators are, how to use them, and in which situations we can use them.

If you want to learn more about how JavaScript works under the hood, you can check out my blog series on how JavaScript works in the browser, explaining the event loop and JavaScript’s memory management.

Debugging code is always a tedious task. But the more you understand your errors, the easier it is to fix them.

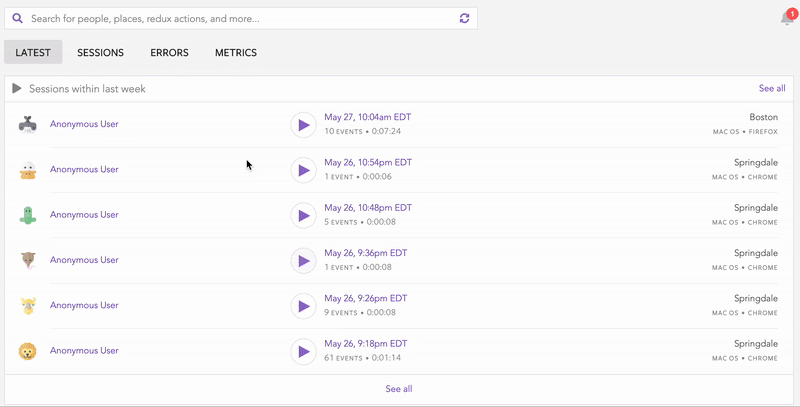

LogRocket allows you to understand these errors in new and unique ways. Our frontend monitoring solution tracks user engagement with your JavaScript frontends to give you the ability to see exactly what the user did that led to an error.

LogRocket records console logs, page load times, stack traces, slow network requests/responses with headers + bodies, browser metadata, and custom logs. Understanding the impact of your JavaScript code will never be easier!

Explore Shadcn UI, a reusable component collection. See its features, pros, cons, and more to determine if you should use it in your project.

Cache components change how rendering decisions are made in Next.js, allowing static and dynamic UI to coexist on the same page without blocking the initial render.

A practical walkthrough of building local-first, privacy-preserving AI agents using small language models.

async/await in TypeScriptTypeScript’s async/await lets you write asynchronous code that reads like synchronous code, making it easier to understand, maintain, and reason about.

Hey there, want to help make our blog better?

Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

Sign up now

5 Replies to "JavaScript iterators and generators: A complete guide"

The arrow functions are not displaying properly in your code snippet examples.

Thanks for catching that. Should be fixed now.

I think generator is also used in express js request handling pipeline

Nice article. I was a little confused by the output shown for the `throw` example, so I tried running a modified version it in the browser.

“`

function* errorGenerator() {

try {

yield ‘one’;

yield ‘two’;

} catch(e) {

console.error(e);

}

yield ‘three’;

yield ‘four’;

}

const errorIterator = errorGenerator();

console.log(errorIterator.next()); // outputs “{ value: ‘one’, done: false }”

console.log(errorIterator.throw(‘Bam!’)); // outputs “Bam!” AND “{ value: ‘three’, done: false }”

console.log(errorIterator.next()); // outputs “{ value: ‘four’, done: false }”

console.log(errorIterator.next()); // outputs “{ value: undefined, done: true }”

“`

It appears that the throw doesn’t actually end the generator, but rather simulate an exception thrown, which is caught by the catch block, then continues the rest of the function normally.

What about return and throw properties??